3D-Printed Coral Reefs: Can We Engineer Marine Recovery?

TL;DR: AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

Picture a shrimp trawler hauling in its catch somewhere off the Gulf Coast. In the old days, that net would trap everything in its path - including endangered sea turtles that drown before reaching the surface. Now, a waterproof camera the size of a smartphone watches every creature that enters the net. When its AI brain spots the distinctive shape of a turtle, a gate swings open. The turtle swims free. The shrimp stay aboard. The boat keeps fishing.

This isn't a prototype gathering dust in some research lab. It's happening right now on commercial vessels from Mexico to Scotland, representing one of the most promising intersections of conservation technology and economic reality we've seen in decades. The question isn't whether smart fishing gear works - it demonstrably does. The question is whether we can scale it fast enough to matter for species that don't have time to wait.

Hundreds of thousands of sea turtles die each year in fishing gear worldwide, with shrimp trawl nets historically representing one of the deadliest threats. Sea turtles need to surface to breathe, so even a brief entanglement can be fatal. For species like loggerheads and Kemp's ridley turtles - already pushed to the edge by coastal development and plastic pollution - every death in a trawl net inches them closer to extinction.

The shrimp industry has known about this problem since the 1970s. In 1987, the United States mandated turtle excluder devices (TEDs) on all trawlers - metal grates installed in nets to guide turtles toward an escape hatch while keeping shrimp in the cod end. Under ideal conditions, these mechanical TEDs test at 97% effectiveness.

But ideal conditions don't exist in commercial fishing. Debris clogs the grates. Fishers worried about losing valuable catch sometimes install TEDs incorrectly or use bar spacing that's too wide. Observer coverage in the southeastern U.S. shrimp fishery hovers around 2%, meaning enforcement depends mostly on the honor system. The field effectiveness of traditional TEDs, researchers acknowledge, often falls far below the 97% design target.

Traditional mechanical TEDs achieve 97% effectiveness in laboratory conditions, but field performance often falls dramatically lower due to debris clogging, improper installation, and the size limitations that prevent large loggerhead and leatherback turtles from escaping through standard hatches.

Meanwhile, fishers face their own existential pressures. When India's trawl fleet failed to meet U.S. standards for TED compliance, the resulting export ban cost the country $500 million - money that disappeared from coastal communities already operating on thin margins. The tension between conservation and commerce felt unsolvable.

What's changed is that technology finally caught up with good intentions.

The first generation of smart fishing gear emerged not from government mandates but from collaborative workshops starting in 2018. Researchers working in Mexico's Gulf of California sat down with local fishers to design solar-powered LED buoys that clip onto gill nets. The idea was simple: turtles have excellent vision, and they instinctively avoid unfamiliar light. If you make nets visible, turtles might steer clear.

Field trials with 28 paired nets - one illuminated, one control - produced dramatic results. The control nets caught 50 green turtles. The lit nets caught 17, all released alive. That's a 63% reduction from a device that costs less than a smartphone and runs for over 132 hours on a single charge. The solar panels recharge automatically during the day, eliminating the waste and expense of disposable batteries or 24-hour chemical light sticks.

"It's a win-win. You get a light that lasts significantly longer without the need for disposable batteries, and you also get a proven reduction in bycatch, one of the greatest threats to sea turtles worldwide."

- Jesse Senko, Lead Researcher

But LED deterrents only work for nets near the surface, and they don't help trawlers working the seafloor. That's where camera systems enter the story.

The technology inside a modern smart trawl reads like something from a submarine thriller. At the heart is a stereo camera system built to withstand crushing pressure and salt corrosion, mounted inside the net's cod-end extension. These aren't consumer-grade action cameras - they're industrial units rated for depths up to 800 meters, sealed in IP68 housings designed for the same environments nuclear engineers worry about.

The camera captures real-time video of every creature entering the net. That footage feeds into a single-board computer - often a Jetson Nano Orin, roughly the size of a credit card - running AI models trained on thousands of marine species images. The computer identifies what it's seeing: shrimp, cod, flounder, or the unmistakable silhouette of a sea turtle.

When the AI detects a protected species, it triggers a mechanical response. In the Smartrawl system developed at Heriot-Watt University, that means rotating a gate mechanism to release the animal back into open water. The entire decision - capture, identify, release - happens in seconds, before the turtle can panic or the crew needs to intervene.

The Smartrawl AI was trained on over 2,900 images covering nine commercial fish species, including everything from cod and haddock to prawns and flatfish. That breadth matters because the system needs to distinguish between a $50 halibut the crew wants to keep and a federally protected turtle that could trigger massive fines.

Commercial underwater camera systems now offer features that would've seemed like science fiction a decade ago: 360-degree robotic pan-tilt mechanisms, wireless data transmission, cloud upload capability, and batteries that record continuously for four days. Some systems offer edge computing that processes footage directly on the device, eliminating the need to transmit gigabytes of video over spotty maritime internet connections.

What makes this technology viable for fishing isn't just the hardware - it's the modular design. The Smartrawl system requires no vessel wiring and can be deployed without major modifications. A crew can install it between fishing trips using basic tools. That matters enormously when you're asking fishers to adopt new equipment while meeting tight seasonal windows and operating with crews that already work 16-hour days.

November 2023 marked a turning point when trials aboard the research vessel Atlantia II off Shetland demonstrated the first successful at-depth rotation of an AI-controlled release gate. The system wasn't perfect - researchers documented issues with latch mechanisms, camera exposure in murky water, and battery failures in harsh winter conditions. But it worked. Video footage showed protected species swimming free while commercial catch remained secure.

By early 2025, subsequent field tests addressed most of the reliability problems. The system now operates autonomously in conditions that would've been impossible just two years earlier. Some fishing operations report up to 90% reduction in accidental catches of endangered species with camera-equipped TEDs - a dramatic improvement over traditional mechanical designs.

The LED technology shows even more immediate promise for certain fisheries. The Mexico trials didn't just reduce turtle bycatch by 63% - they did it in a way fishers could immediately implement. The solar-powered buoys cost a fraction of camera systems and require minimal training to use. Partnership with commercial manufacturer Fishtek Marine means units could reach mass production within 2-3 years.

Traditional mechanical TEDs, meanwhile, continue showing benefits despite their limitations. Field trials in Odisha, India using a NOAA-approved design showed less catch loss, better appearance of the catch, and reduced waste materials in the cod end. The key insight: properly designed TEDs don't just save turtles - they can actually improve fishing operations by filtering debris and reducing drag.

"From trials, we can show how catch quantity has increased because the catch comes to the cod end without any debris. Consequently, dragging pressure has decreased, which means lesser diesel consumption. Plus, the conservation of sea turtles. It makes absolute sense to implement TEDs."

- Marine Products Export Development Authority Official

But aggregate statistics only tell part of the story. Underwater cameras deployed by fishermen like Ian Wightman revealed seal behavior nobody had documented before - animals thumping the cod end to force fish through the mesh. These unexpected insights help designers refine both the mechanical and AI components of smart TEDs, creating a continuous improvement cycle that traditional gear could never match.

Here's where conservation theory collides with financial reality: camera systems aren't cheap. Professional-grade underwater equipment with AI processing can run anywhere from $50,000 to $500,000 per vessel depending on configuration and monitoring scope. For a small shrimp boat operating on margins measured in cents per pound, that's a business-ending expense.

Which is why the economics only work when subsidies enter the equation. Government grants and programs like the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund cover up to 60% of technology adoption costs. That still leaves tens of thousands of dollars for vessel operators, but it moves the investment from impossible to merely difficult.

The business case for smart fishing technology improves dramatically when you consider the penalties for non-compliance: India's shrimp industry lost $500 million in U.S. export revenue due to TED violations - dwarfing any installation cost and demonstrating that conservation technology is often cheaper than the alternative.

The business case improves when you factor in the stick alongside the carrot. India's shrimp industry learned this the hard way - losing access to the massive U.S. market cost them Rs. 4,500 crores per year, dwarfing any TED installation expense. For exporters serving markets with strict environmental standards, smart monitoring systems aren't optional - they're the price of staying in business.

There are operational benefits too, though they vary widely by fishery. Reduced drag from debris-free nets cuts fuel consumption, which matters when diesel represents one of the biggest variable costs. Better catch quality means higher prices at dock. And video documentation provides liability protection if questions arise about bycatch compliance or gear performance.

The training requirements remain a significant hurdle. AI-powered systems need crew members who can troubleshoot software issues, not just mend nets and clean fish. That's a different skill set, one that older generations of fishers often lack. Successful implementations typically pair technology installation with comprehensive training programs and ongoing technical support - another cost that grant funding needs to cover.

Solar LED buoys sidestep many of these problems by being simple enough that any crew can understand them at a glance. You charge them, clip them on, and they work. The lower cost - comparable to a quality marine GPS unit - puts them within reach of independent operators in developing nations where most gillnet fishing happens. Dr. Sarah Chen, commenting on the LED technology, emphasized its "simplicity and cost-effectiveness" as key factors driving adoption.

The regulatory landscape for electronic monitoring remains fragmented and often contradictory. NOAA requires all U.S. vessels fishing federal waters to have BRDs and TEDs installed, but camera systems aren't yet mandated - they're optional upgrades. Observer coverage, the traditional enforcement mechanism, remains below 1% in many regions with goals to reach 5% in five years.

That creates a curious situation where we have technology that works better than human observers, costs less in the long run, and provides complete documentation of every trawl - yet adoption depends on voluntary participation or export market pressure rather than domestic law. The Inter-American Convention mandates TED usage across multiple Caribbean and Latin American countries, but the European Union has no such requirement for shrimp exporters.

India's experience offers a cautionary tale about regulatory harmonization. When U.S. inspectors found Indian TEDs didn't meet NOAA standards for bar spacing - specifically the requirement for 4-inch spacing to prevent small turtles from entering - the entire industry faced export bans. Indian researchers had widened the bars to 145mm to let larger fish through, benefiting fishers but creating compliance problems.

The back-and-forth that followed illustrates why smart monitoring systems might ultimately prove easier to regulate than mechanical designs. Principal scientist M.P. Remesan explained: "We fine-tuned and improved our TED to achieve their standards. We then took it to America for a dive evaluation... They suggested some improvements, which we incorporated." That iterative process of mechanical adjustment takes months or years. With camera systems, software updates can happen overnight, adjusting species recognition parameters or release thresholds without modifying physical hardware.

NOAA's observer programs, operating since 1987 in the Gulf, evolved from simple TED compliance checks to comprehensive biological, vessel, and gear selectivity studies. That regulatory infrastructure could readily incorporate electronic monitoring data - in fact, video footage provides far more detail than a human observer could possibly document during a single trip.

Technology adoption in fishing communities follows different patterns than in Silicon Valley. You're not convincing early adopters to buy the newest iPhone - you're asking people whose families have fished the same waters for generations to trust machines with their livelihoods.

The workshops that produced the solar LED buoys offer a model. Researchers began collaborating with fishers in 2018, letting them specify design preferences and adapt prototypes to local practices. Several fishers became co-authors on the resulting scientific papers. That co-development approach built trust and produced technology that actually worked in real-world conditions, not just controlled experiments.

Compare that to top-down mandates that treat fishers as problems to be solved rather than partners. Resistance to traditional TEDs often stemmed from legitimate concerns about catch loss and operational complexity, not malice toward turtles. When fishers see that improved TED designs can actually increase catch quality and reduce fuel costs, opposition fades.

Camera documentation provides another unexpected benefit: it protects good operators from being lumped in with bad ones. A vessel with complete video records can prove compliance instantly, potentially avoiding costly inspections or defending against false accusations. That appeals to fishing operations concerned about their reputation and market access.

The smartrawl team discovered this during trials when fishermen realized the footage showed exactly how their gear performed underwater - information they'd never had access to before. Seeing seals manipulate nets in ways they'd only suspected led to design changes that improved performance. The cameras became tools for optimization, not just compliance.

Five species of sea turtles affected by shrimp trawling have shown vast improvement except for loggerheads, according to NOAA research. That partial success highlights both how far we've come and how much remains uncertain. Loggerheads grow larger than most TED escape hatches, creating a size mismatch that mechanical designs can't easily solve. Camera systems with species-specific protocols might handle that better, but we don't yet have enough data to know.

The research completeness score for this topic sits at just 58% - a reminder of how much we're still figuring out. We don't have solid numbers on how many vessels worldwide currently use camera-based monitoring, or comprehensive cost-benefit analyses across different fisheries. Survival rates for turtles released through smart systems need more documentation. The data collection pipeline from boat cameras to conservation databases remains patchwork.

What we do know suggests cautious optimism. Studies from the National Marine Fisheries Service, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, and Texas Parks and Wildlife indicate that current practices aren't likely to cause serious risk or hinder recovery of most affected species. But "not likely to cause serious risk" sets a pretty low bar when you're talking about animals that were nearly extinct a generation ago.

Co-development between researchers and fishing communities represents a breakthrough in conservation technology adoption. When fishers help design the tools they'll use - as with the Mexico LED buoy project - resistance disappears and real-world performance improves dramatically compared to top-down mandates.

The goal isn't just preventing extinction - it's rebuilding populations to where these magnificent animals once again fill their ecological roles as major grazers of seagrass beds and jellyfish populations. That requires not just reducing mortality but getting it close to zero in the most critical habitats and life stages.

Where does smart fishing gear go from here? The near-term roadmap focuses on reliability and cost reduction. Phase 6 trials of the Smartrawl system aim to address the exposure problems and battery failures that plagued early deployments. Manufacturing partnerships will drive down per-unit costs through economies of scale.

Cloud connectivity opens possibilities that sound almost absurd until you remember we're living in an era when your refrigerator texts you about expired milk. Fishing vessels with satellite uplinks could stream monitoring data in real-time to regulatory databases, creating a transparent chain of custody for every catch. AI models could improve continuously as they process more footage, getting better at distinguishing similar-looking species or detecting injuries that might affect post-release survival.

Predictive systems might eventually avoid bycatch before it happens. If cameras and sensors detect high concentrations of turtles in a particular area, they could alert the crew to move or trigger preventive measures automatically. Machine learning algorithms could identify environmental conditions - water temperature, time of day, current patterns - that correlate with elevated bycatch risk.

The CC-Bio system from CatchCam Technologies already demonstrates some of these capabilities, offering AI-powered species identification and behavior analysis with on-site edge processing. Their biodiversity monitoring work isn't directly focused on fishing gear, but the underlying technology transfers readily to bycatch applications.

Integration with other monitoring systems could provide fleet-wide insights impossible to obtain from individual vessels. If 100 boats share camera data, you'd quickly build comprehensive maps of where and when protected species concentrate - information valuable for conservation planning as well as helping fishers avoid conflicts.

Sea turtles take decades to reach reproductive age. A loggerhead hatched today won't lay her first eggs until 2050 or later. That glacial reproductive cycle means populations lag years behind changes in mortality rates, for better or worse. We might not see the full impact of smart fishing technology until today's children are buying shrimp for their own families.

Which makes speed of adoption critical. Every year of delay means thousands more turtles die in situations where existing technology could save them. The solar LED buoys especially frustrate conservationists because they work, they're affordable, and they're ready to manufacture at scale - yet deployment remains limited to experimental fleets and research partnerships.

Regulatory agencies face a difficult balance. Mandate technology adoption too aggressively, and you risk bankrupting small operators or driving fishing into unregulated black markets. Move too slowly, and species slide toward extinction while we study the problem to death. The ideal approach probably involves tiered requirements: expensive camera systems for large commercial vessels and export operations, simpler LED solutions for small-scale fishers in developing nations, with grant funding to ease transitions.

The technical challenges pale beside the social and economic ones. Engineers have largely solved the hardware problems - cameras that survive trawling conditions, AI that identifies marine species accurately, power systems that last for full fishing trips. What we haven't solved is how to retrofit a global industry employing millions of people, many of them operating at subsistence level, with expensive technology in a timeframe measured in years rather than decades.

This story about smart fishing gear is really about whether humans can figure out how to share the ocean without destroying what makes it worth sharing. Sea turtles survived the dinosaur extinction, outlasted the ice ages, and swam the oceans for 100 million years. They might not survive us.

But they could. The technology exists. The economic models exist, at least in outline. We know what works and roughly what it costs. What's missing is the collective will to fund and implement solutions at the scale required, which means convincing skeptical fishing communities, appropriating funds from budget-conscious governments, and sustaining effort across election cycles and shifting political priorities.

The camera systems watching shrimp nets in the Gulf aren't just protecting turtles - they're demonstrating a template for how conservation and commerce might coexist in the 21st century. Not through hectoring lectures about saving the planet, but through technology that makes good practices easier and more profitable than destructive ones.

Whether that template scales to industrial fishing worldwide, to agriculture, to resource extraction industries that make far more money than shrimp boats ever will - that's the real test ahead. The turtles swimming free through smart release gates are the proof of concept. What we do next determines whether it stays a clever proof or becomes the future we actually build.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

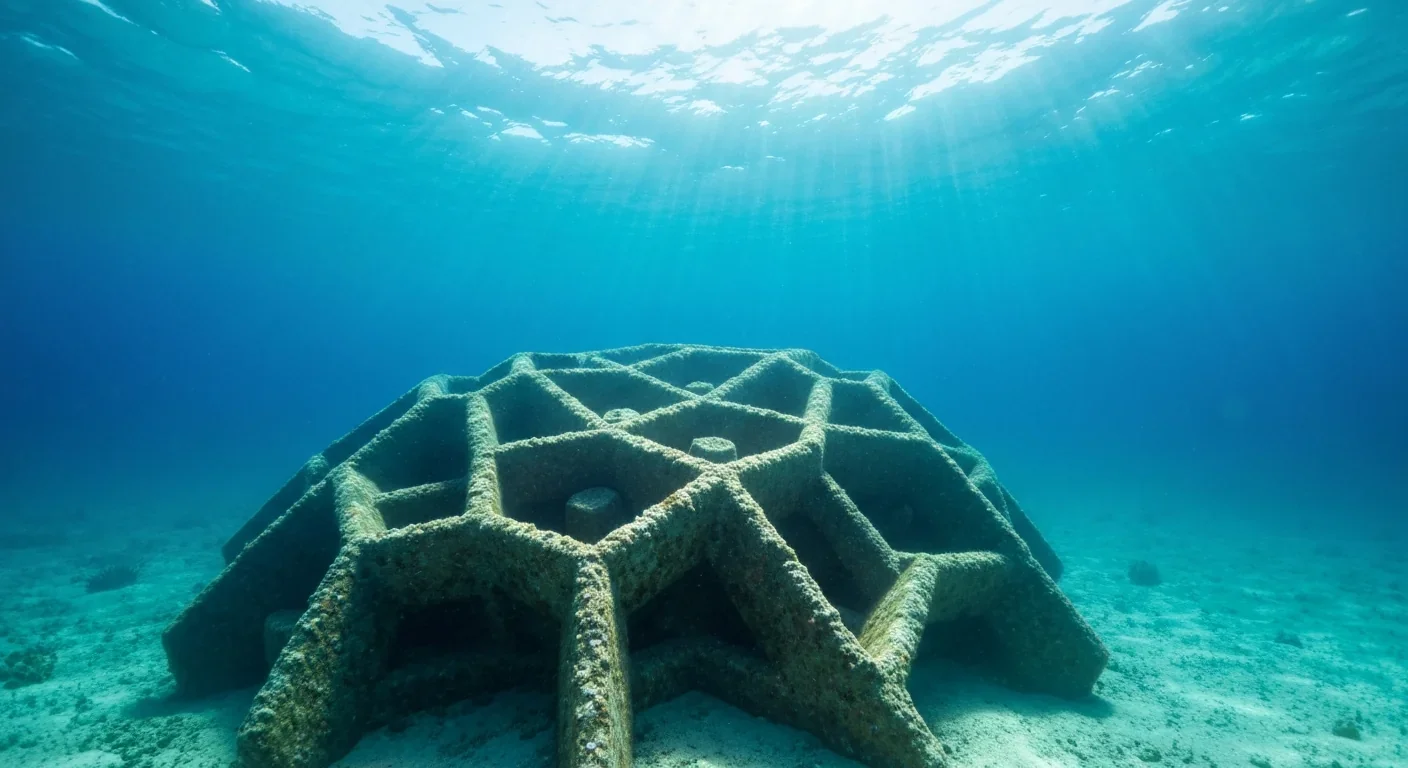

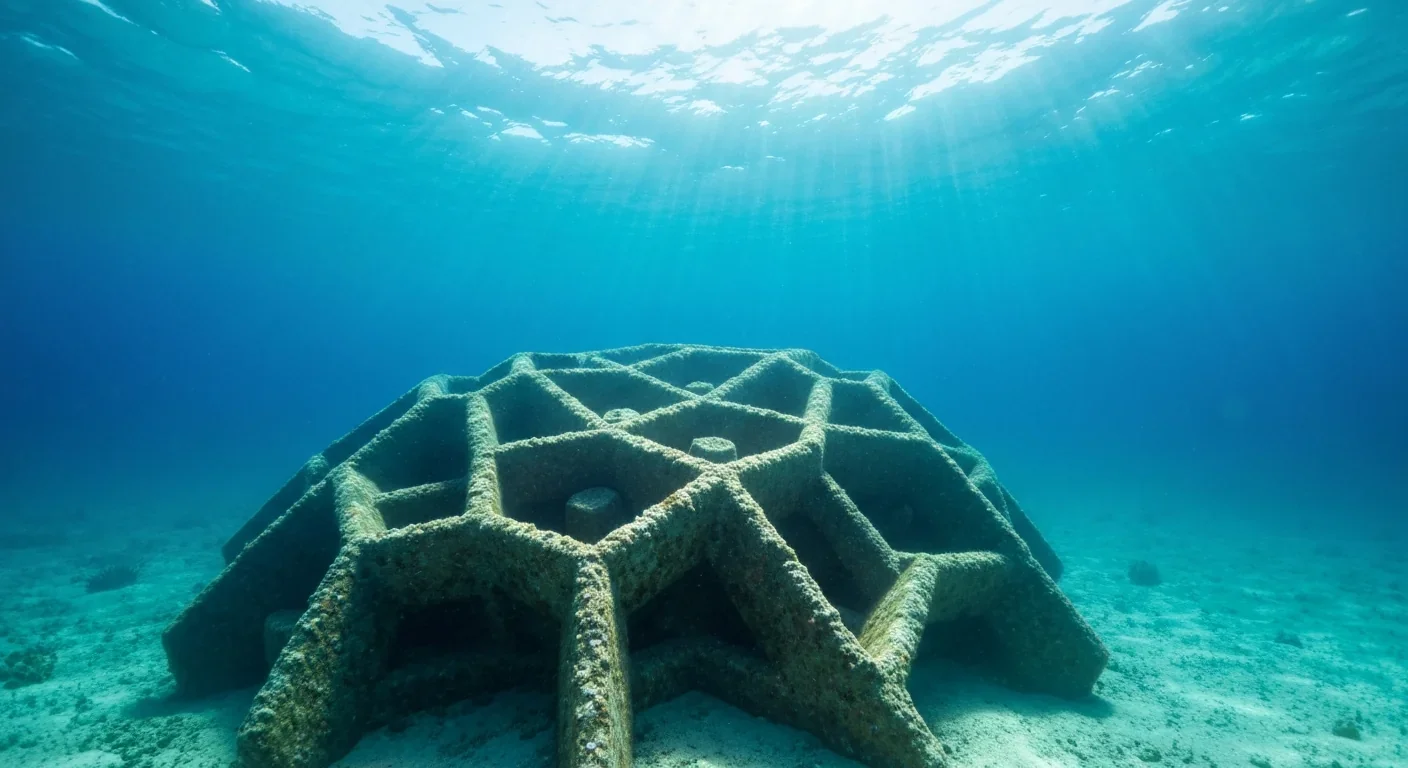

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

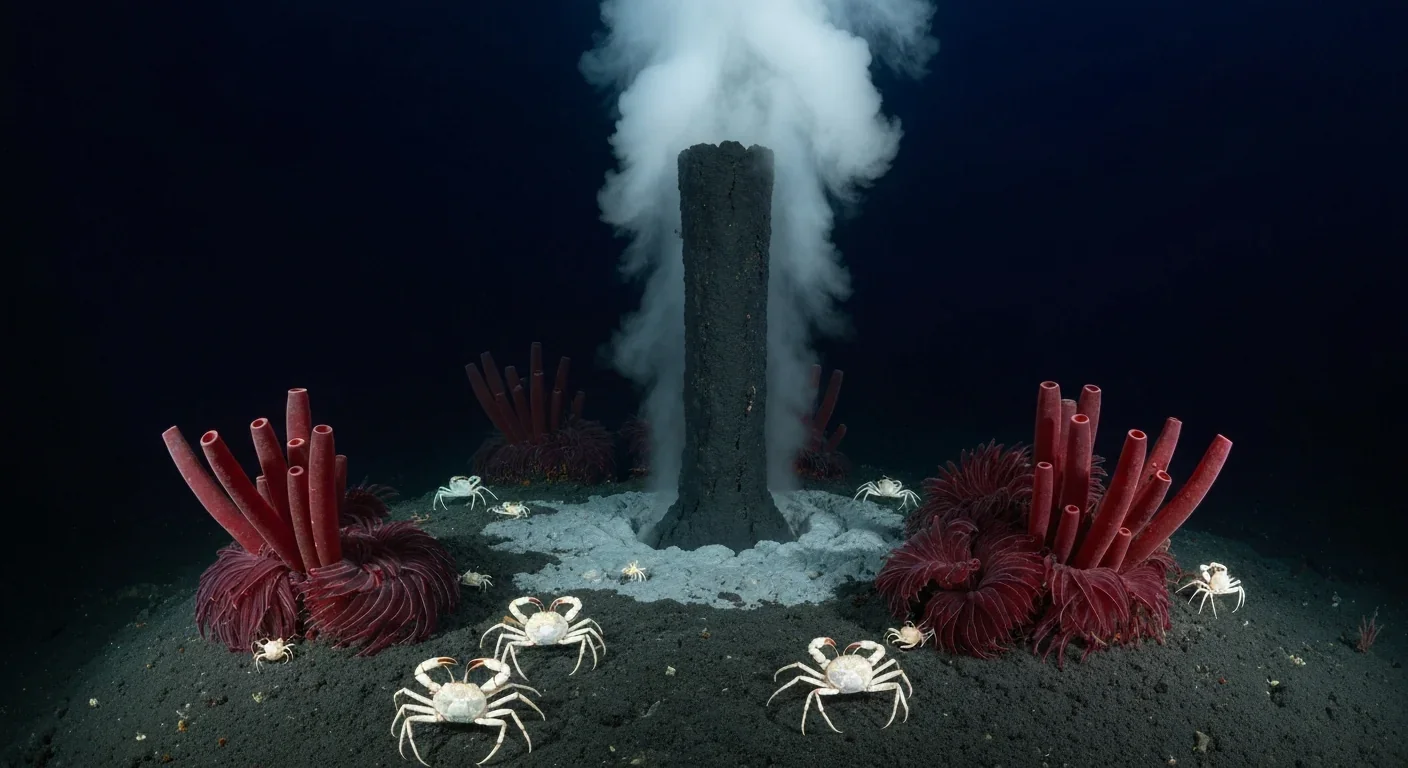

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

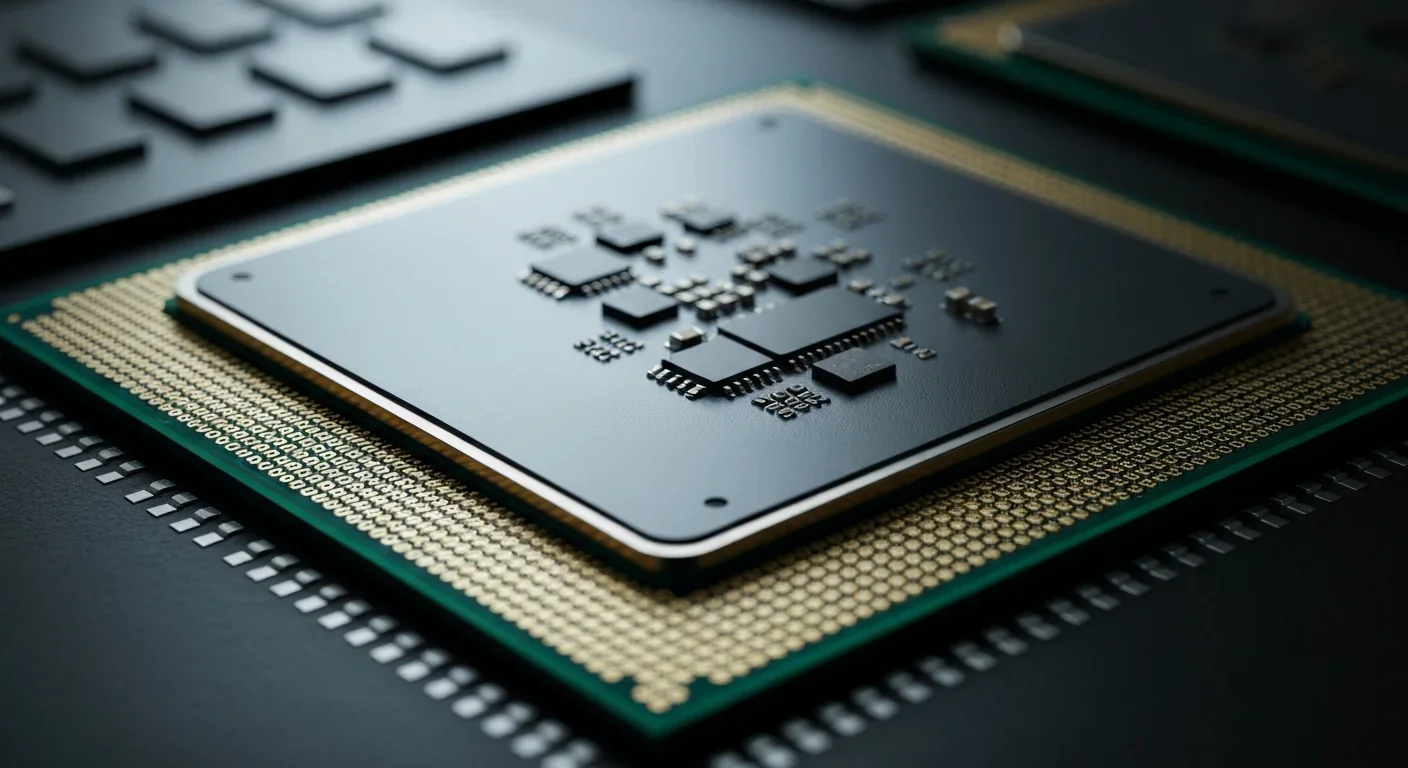

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.