The Repair Revolution: Why Fixing Things Saves the Planet

TL;DR: Scientists are transforming wood into viable battery components using nanocellulose, potentially replacing problematic lithium-ion materials with renewable forest-based alternatives. While energy density gaps remain, the technology shows promise for applications prioritizing safety, sustainability, and biodegradability over maximum power.

What if the solution to our battery crisis was already growing in managed forests across the globe? While the world races to mine enough lithium, cobalt, and rare earth metals to power the electric revolution, researchers have been quietly engineering one of Earth's most abundant natural polymers into functional battery components. They're using sustainably harvested wood.

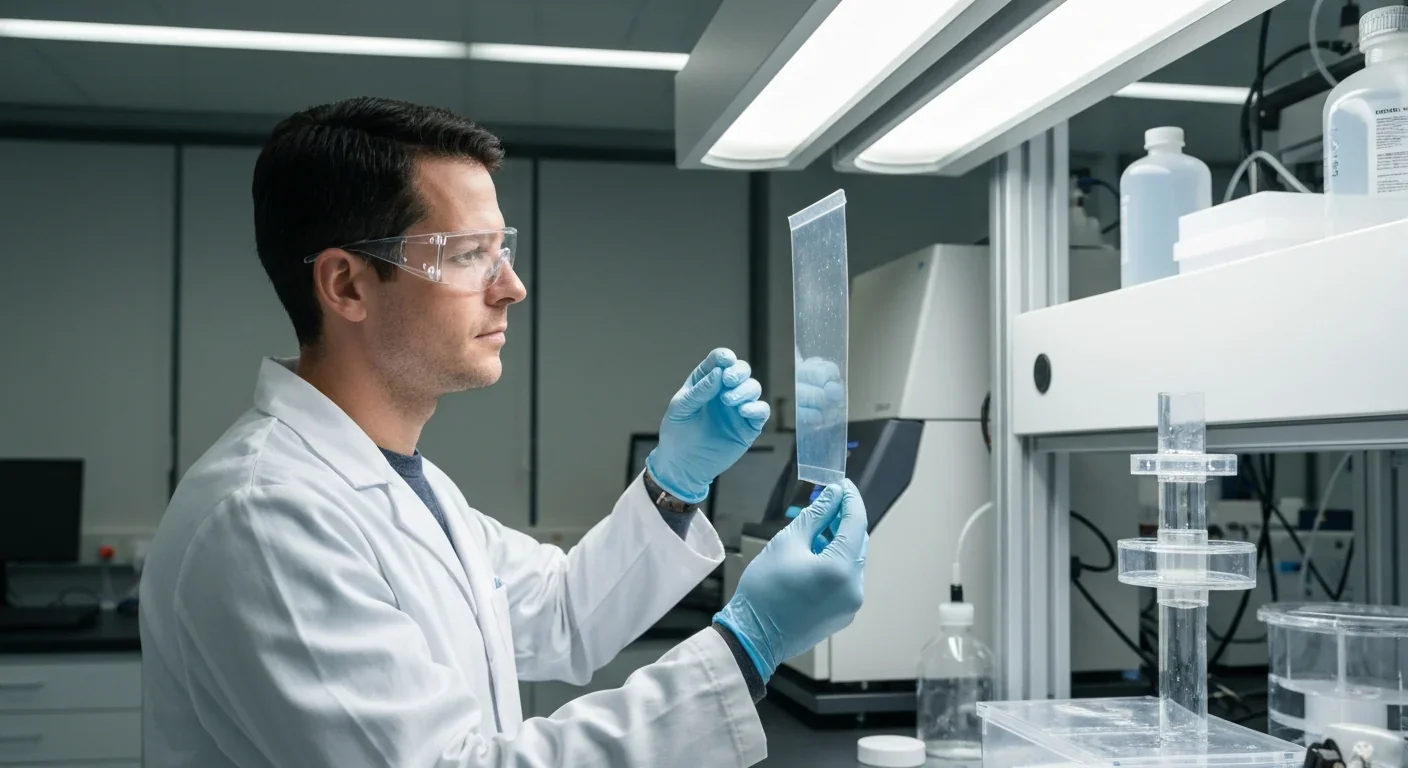

The innovation hinges on nanocellulose, the microscopic fibers that give trees their structural integrity. When processed at the nanoscale, these wood-derived materials exhibit surprising electrochemical properties that make them viable candidates for battery separators, solid-state electrolytes, binders, and even carbon electrodes. The implications reach far beyond materials science. If cellulose-based batteries can scale from lab prototypes to commercial production, they could help defuse the environmental time bomb ticking inside the lithium-ion battery supply chain.

The global battery market is projected to explode over the next decade, driven by electric vehicles, grid storage, and portable electronics. But the materials that power today's batteries come with serious baggage. Lithium mining devastates water tables in fragile ecosystems. Cobalt extraction relies on conflict-zone supply chains with documented human rights abuses. And when batteries reach end-of-life, they become hazardous waste laden with toxic solvents and non-biodegradable polymers.

Traditional lithium-ion batteries use petroleum-derived polyethylene or polypropylene separators, liquid electrolytes containing flammable organic solvents, and electrode binders made from synthetic polymers. Each component carries environmental costs in manufacturing, use, and disposal. The European Union's new battery regulations now mandate recycled content and sustainability reporting, putting pressure on manufacturers to find greener alternatives.

Enter the forest products industry, an unexpected player in the energy transition.

Nanocellulose production shares DNA with traditional papermaking but operates at a different scale entirely. Researchers isolate individual cellulose fibers from wood pulp using mechanical grinding, chemical treatments, or enzymatic processes. The result is cellulose nanofibrils (CNF) or cellulose nanocrystals (CNC), materials with diameters measured in nanometers but lengths extending to micrometers.

These nano-scale materials possess remarkable mechanical strength, high surface area, thermal stability, and crucially, the ability to conduct ions when properly engineered. Swedish researchers at Linköping University demonstrated how copper-infused nanocellulose can serve as a solid-state electrolyte, eliminating the flammable liquid solvents that make conventional batteries prone to thermal runaway.

The science gets interesting when you understand how copper acts as a molecular gatekeeper. By controlling the spacing between cellulose chains, researchers can create pathways for lithium ions to flow while maintaining structural integrity.

The result is a solid electrolyte that can't leak, doesn't combust, and remains stable across temperature extremes.

Wood-derived cellulose isn't limited to a single battery component. It's being engineered into at least four distinct applications, each addressing a different bottleneck in battery design.

Battery separators are the thin membranes that prevent positive and negative electrodes from touching while allowing ions to pass through. Cellulose-based separators offer superior thermal stability compared to conventional polyethylene. When a lithium-ion battery overheats, plastic separators can melt and cause short circuits. Cellulose separators maintain structural integrity at higher temperatures, providing a critical safety margin.

Japanese manufacturer NAGASE has developed cellulose separators that combine the material's natural flame resistance with engineered porosity for optimal ion flow. Their products target industrial battery applications where safety is paramount.

Solid-state electrolytes represent the holy grail of battery innovation because they eliminate dendrite formation, the needle-like lithium deposits that pierce conventional separators and cause battery failure. Research from Swedish universities shows that copper-nanocellulose composites can achieve ionic conductivity levels approaching those of liquid electrolytes while offering the safety benefits of solid materials.

The technology works because the copper creates regular spacing between cellulose chains, forming nanoscale highways for lithium ions. Unlike liquid electrolytes that allow dendrite growth, the rigid structure of cellulose prevents lithium from forming dangerous deposits.

Binders hold active electrode materials together and maintain electrical contact. Traditional binders use synthetic polymers derived from petroleum. Nanocellulose binders provide mechanical strength and thermal stability while being completely biodegradable. When batteries reach end-of-life, cellulose binders break down naturally rather than persisting as microplastic pollution.

"By localizing a cost-competitive graphite supply in the U.S. using local forestry resources, we provide manufacturers with a stable, scalable and sustainable alternative - while mitigating environmental impact and supply-chain risks."

- Vincent Ledoux-Pedailles, CarbonScape Chief Commercial Officer

Carbon electrodes take the innovation one step further. Researchers have developed processes to carbonize cellulose, transforming wood fibers into graphite-like materials suitable for battery anodes. New Zealand startup CarbonScape has commercialized a process that converts wood chips into battery-grade graphite using a proprietary carbonization method that avoids the toxic chemicals typical of conventional graphite production.

The company positions wood-derived graphite as a domestic alternative to imported materials. The United States is currently the world's third-largest exporter of wood chips, shipping $336 million worth overseas in 2023. CarbonScape argues this raw material could instead feed a domestic battery supply chain, reducing dependence on foreign graphite sources.

One of the most radical applications comes from research on fully biodegradable batteries. Scientists at Empa, Switzerland's federal materials research lab, created a battery made almost entirely from cellulose. The design uses cellulose nanofibers as the substrate, carbon-coated cellulose as electrodes, and a hydrogel electrolyte. The entire device can biodegrade in soil within months.

The breakthrough relied on a clever use of 3D printing. Researchers printed electrodes onto cellulose films using conductive inks, then laminated the layers into a functional battery. While the power density remains far below lithium-ion levels, the proof-of-concept demonstrates that entirely bio-based, disposable batteries are technically feasible.

Applications include single-use medical sensors, environmental monitoring devices that don't need recovery, and packaging-integrated electronics that biodegrade along with their cardboard containers.

The nanocellulose materials market was valued at $608.7 million in 2025 and is projected to reach $4.7 billion by 2035, growing at 19.3% annually. While batteries represent just one application among many for nanocellulose, the growth trajectory signals investor confidence and industrial scale-up.

Canadian company CelluForce, a joint venture between Domtar and FPInnovations, operates one of the world's largest nanocellulose production facilities. Originally focused on composites and coatings, the company is exploring energy storage applications as battery manufacturers seek sustainable materials.

European forestry giant Stora Enso has expanded its bio-based materials portfolio, ramping up nanocellulose production capacity in the Nordic region. The company positions itself at the intersection of traditional forestry and advanced materials, leveraging existing pulp mills that can be adapted for nanocellulose extraction with incremental capital investment.

The paper and pulp industry sees nanocellulose as a strategic pivot as demand for traditional paper products declines. Fiber-to-fiber bonding techniques developed for papermaking can potentially be adapted to create integrated battery architectures with minimal post-processing, leveraging decades of process expertise.

The critical question is how cellulose-based batteries stack up against conventional lithium-ion technology in the metrics that matter: energy density, cycle life, and charging speed.

Energy density remains the biggest gap. Lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles typically deliver 250-300 watt-hours per kilogram. Early cellulose-based designs achieve 50-100 watt-hours per kilogram. That's fine for stationary storage where weight doesn't matter, but it's a non-starter for vehicles.

Cycle life shows more promise. Flexible batteries using lignin-based electrolytes have demonstrated thousands of charge-discharge cycles while maintaining capacity. Lignin, a woody polymer that's typically burned as waste in paper mills, can be processed into conductive materials suitable for battery components. Using lignin creates a circular economy model where waste streams become feedstock.

Charging speed depends heavily on battery architecture. Solid-state cellulose electrolytes can potentially enable faster charging than liquid electrolytes because they eliminate the lithium plating issues that force conservative charging protocols.

However, real-world demonstrations remain limited to lab conditions.

The sustainability case for cellulose batteries depends entirely on responsible forestry practices. North American and European forests operate under certification systems that ensure replanting, biodiversity protection, and carbon sequestration. When managed properly, these forests represent renewable resources that sequester carbon as they grow and provide raw materials when harvested.

The math works like this: trees absorb carbon dioxide as they grow. When harvested sustainably, they're replaced by young trees that continue absorbing carbon. If the wood is processed into long-lasting battery components rather than burned, that carbon remains sequestered. At end-of-life, cellulose components can biodegrade naturally or be composted, returning nutrients to soil.

This creates a fundamentally different lifecycle than mining. Lithium deposits don't regenerate. Cobalt mines don't sequester carbon. But a well-managed forest can supply battery materials indefinitely while providing ecosystem services.

The model isn't without complications. Industrial forestry faces valid criticism about monoculture plantations, habitat fragmentation, and indigenous land rights. The industry will need to prove it can scale cellulose production without replicating the environmental damage that made lithium mining controversial in the first place.

Alternative battery chemistries face a familiar challenge: breaking into a market dominated by proven lithium-ion technology with enormous manufacturing scale and falling costs. Wood Mackenzie's 2026 energy storage trend predictions identify alternative chemistries as an area of growing interest but note that commercialization timelines remain uncertain.

Cellulose batteries will likely enter the market through niche applications before competing in mainstream uses. Early targets include:

Single-use medical devices where biodegradability eliminates disposal concerns and low power density isn't a limitation. Temporary pacemakers, drug delivery systems, and diagnostic sensors could use cellulose batteries that naturally break down in the body.

Wearable electronics benefit from cellulose's flexibility. Researchers have demonstrated batteries that can twist, bend, and stretch while maintaining electrical contact, something rigid lithium-ion cells cannot do.

"In the battery sector, nanocellulose is being used as a binder and separator material due to its mechanical strength and thermal stability."

- Research Nester market analysis

Grid storage applications where weight doesn't matter and safety is paramount could adopt cellulose-based systems that eliminate fire risk. Stationary storage for renewable energy integration values long cycle life and low maintenance over high energy density.

Safety-critical applications in aerospace, subsea operations, or hazardous environments could justify the performance trade-off in exchange for batteries that won't combust even under extreme conditions.

The technology faces real barriers to mass adoption. Manufacturing processes need to scale beyond lab quantities while maintaining quality. Supply chains must be established. Performance gaps must narrow. And cellulose batteries need to prove themselves in years-long field trials before risk-averse industries commit.

Within the next five years, expect to see cellulose battery components in commercial products, starting with specialized applications. Market analysts project significant growth in nanocellulose production capacity, driven by multiple industries beyond just batteries.

The forestry industry stands at an inflection point. Paper consumption continues declining in developed economies, forcing companies to find new markets for forest products. Battery materials represent a high-value application that could absorb significant production capacity.

Research institutions in Sweden continue pushing the boundaries of solid-state cellulose electrolytes. Swiss laboratories refine biodegradable designs. Universities worldwide publish research demonstrating new configurations and improved performance.

The technical questions that remain unanswered include whether cellulose batteries can achieve energy densities competitive with lithium-ion, how production can scale to gigawatt-hour levels, and whether forestry supply chains can meet demand without compromising sustainability principles.

Cellulose batteries represent one thread in a larger tapestry of battery innovation. Dozens of startups are pursuing alternative chemistries, from sodium-ion to solid-state lithium-metal designs. The battery landscape is diversifying because no single technology will meet every application's needs.

Wood-derived batteries won't replace lithium-ion in electric vehicles anytime soon. But they don't have to. If cellulose can capture 10% of the global battery market in applications where its advantages matter most, that would still represent billions of dollars in annual production and millions of tons of materials diverted from mining to sustainable forestry.

The environmental calculation extends beyond just the battery itself. When forests are managed for continuous harvest and replanting, they create permanent carbon sinks. When battery materials biodegrade rather than accumulating in landfills, they close nutrient loops. When battery production doesn't require devastated landscapes and water depletion, it reduces the total environmental burden of the energy transition.

The advantage cellulose brings is abundance, renewability, and existing industrial infrastructure that can be adapted rather than built from scratch.

Wikipedia documents the long history of paper battery research, stretching back decades. What's changed isn't the fundamental science but the manufacturing capability, market pressure for sustainable materials, and regulatory environment that now rewards innovation in bio-based materials.

The solid-state electrolyte field has expanded dramatically, with cellulose representing one of many candidate materials.

If you own electronic devices, drive an electric vehicle, or simply care about reducing environmental impact, the battery chemistry debate affects you directly. The current trajectory has us mining ever-increasing quantities of materials with finite reserves and serious extraction costs.

Cellulose batteries won't solve every problem, but they demonstrate that alternatives exist. They show that the energy transition doesn't have to replicate the extractive industries of the fossil fuel era. And they prove that sometimes the most advanced technology comes from redesigning the most ancient materials.

The next decade will determine whether wood-based batteries remain a laboratory curiosity or become a significant part of the energy storage mix. The science is validated. The market potential is clear. The environmental case is compelling. What remains is execution: scaling production, proving reliability, and building supply chains that honor sustainability principles.

You'll know the inflection point has arrived when major battery manufacturers announce partnerships with forestry companies, when building codes start specifying cellulose-based batteries for fire safety, and when recycling programs add "compostable battery" categories.

Until then, the transformation is happening in research labs, pilot production facilities, and boardrooms where strategists are placing bets on which battery chemistries will dominate the 2030s.

The trees, at least, are ready.

Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at our galaxy's center, erupts in spectacular infrared flares up to 75 times brighter than normal. Scientists using JWST, EHT, and other observatories are revealing how magnetic reconnection and orbiting hot spots drive these dramatic events.

Segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) colonize infant guts during weaning and train T-helper 17 immune cells, shaping lifelong disease resistance. Diet, antibiotics, and birth method affect this critical colonization window.

The repair economy is transforming sustainability by making products fixable instead of disposable. Right-to-repair legislation in the EU and US is forcing manufacturers to prioritize durability, while grassroots movements and innovative businesses prove repair can be profitable, reduce e-waste, and empower consumers.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

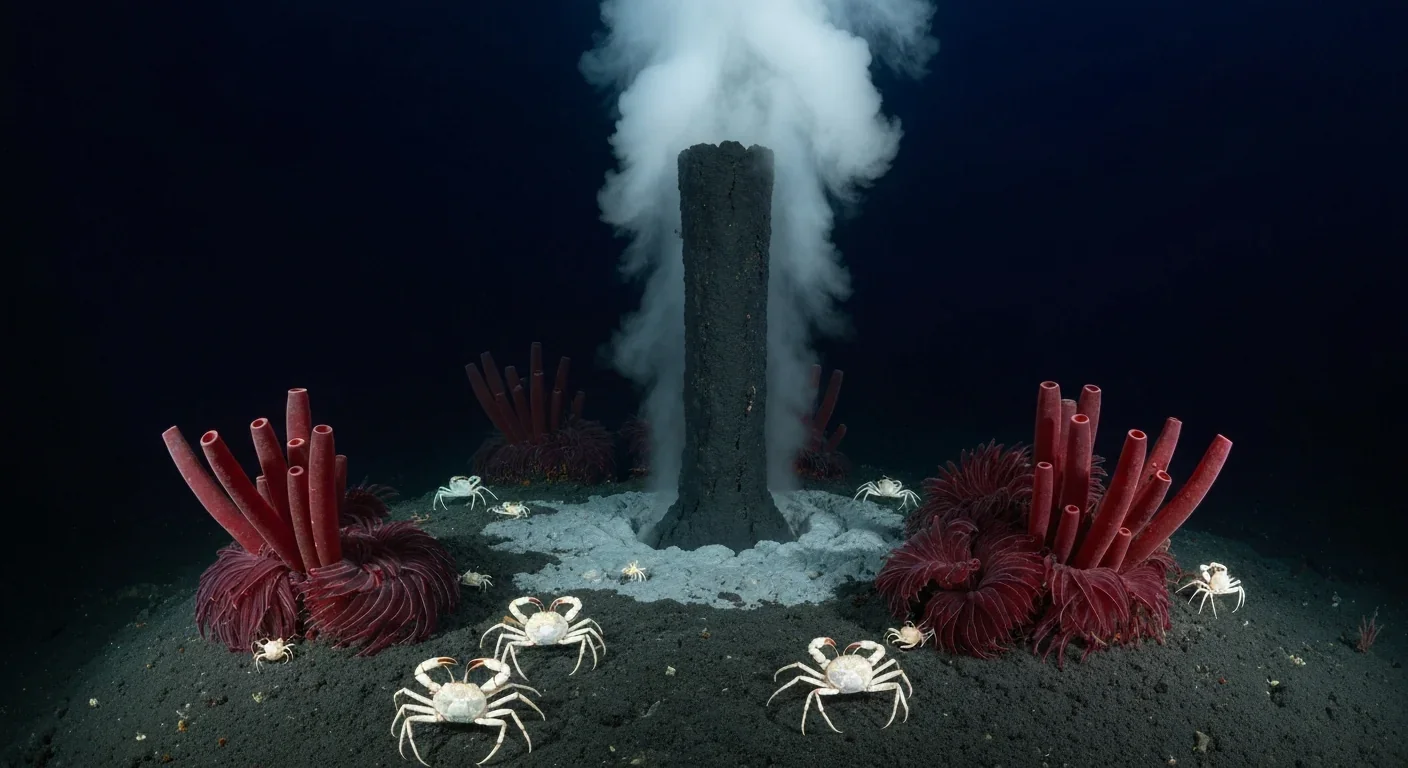

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Library socialism extends the public library model to tools, vehicles, and digital platforms through cooperatives and community ownership. Real-world examples like tool libraries, platform cooperatives, and community land trusts prove shared ownership can outperform both individual ownership and corporate platforms.

D-Wave's quantum annealing computers excel at optimization problems and are commercially deployed today, but can't perform universal quantum computation. IBM and Google's gate-based machines promise universal computing but remain too noisy for practical use. Both approaches serve different purposes, and understanding which architecture fits your problem is crucial for quantum strategy.