The Repair Revolution: Why Fixing Things Saves the Planet

TL;DR: Alpine glaciers are being wrapped in reflective blankets that cut melt by 50-70% in covered areas, but the practice only protects tiny fractions of ice at costs of hundreds of thousands of euros per hectare. While the science works locally, experts debate whether it's meaningful climate action or an expensive distraction from the emissions cuts that actually determine glacier survival.

By 2050, the Alps could lose nearly all their glaciers. Scientists project that at current melt rates, these ancient ice giants that have shaped European culture, water supplies, and tourism for millennia will simply vanish. So when Swiss ski resort workers began draping massive reflective blankets over vulnerable patches of ice, what started as a desperate bid to preserve winter slopes has sparked one of climate adaptation's most fascinating debates: Can we save glaciers by tucking them in?

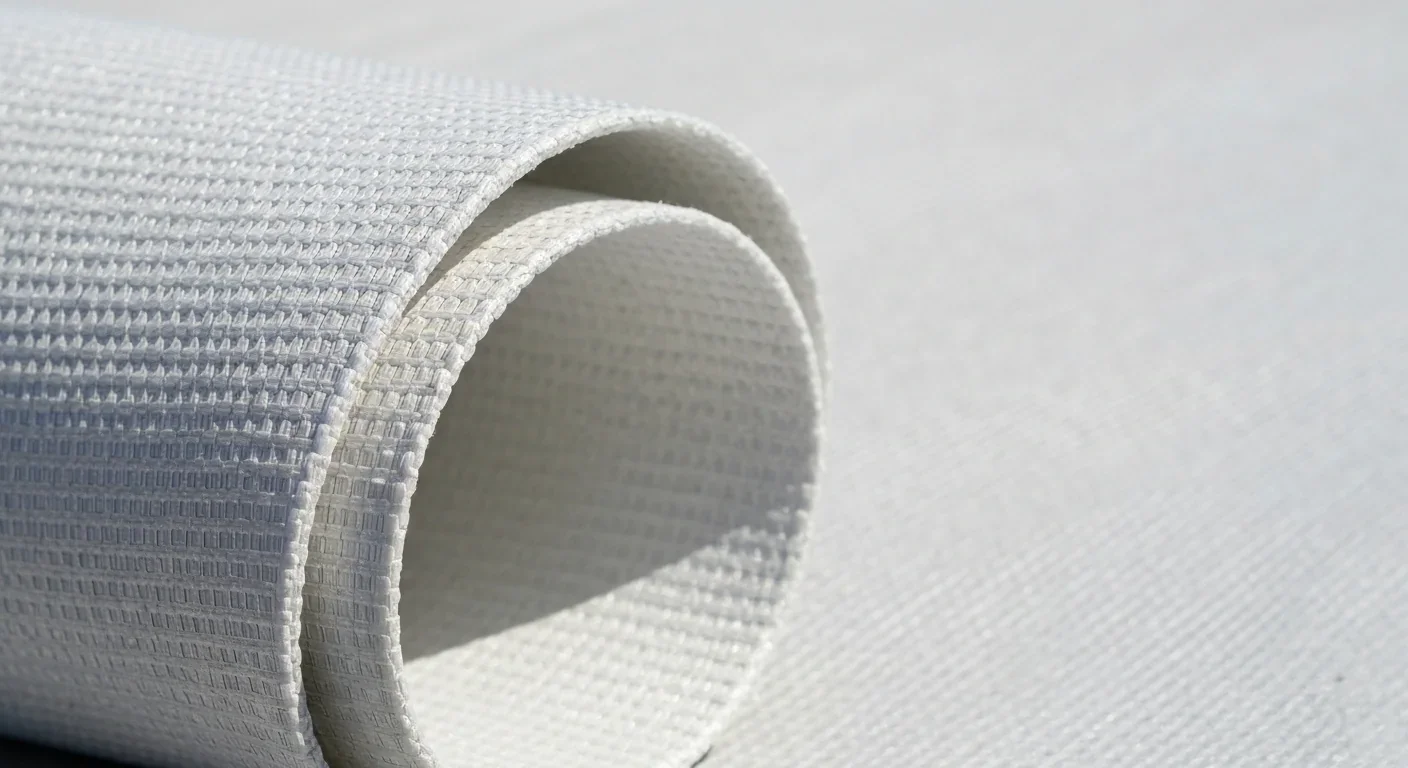

The practice sounds absurd - wrapping something as vast and powerful as a glacier in what amounts to a giant tarp. Yet across Switzerland, Italy, Austria, and now China, teams deploy thousands of square meters of specialized geotextile fabric each summer, creating surreal landscapes where brilliant white sheets cascade down mountainsides like enormous bandages. The physics are straightforward: these UV-resistant blankets reflect solar radiation and insulate ice from warm air, reportedly cutting summer melt by 50 to 70 percent in covered areas. That's not theoretical - it's measured, documented, repeatable science.

But here's the catch that's driving glaciologists, economists, and environmentalists into fierce camps: Alpine glaciers have lost roughly 39 percent of their mass since 2000, with the pace accelerating year after year. Switzerland alone shed 3 percent of its remaining ice in a single year, the fourth-largest annual loss on record. When you're hemorrhaging ice at that rate, covering a few hectares feels less like climate action and more like bringing a teaspoon to a flood.

The technology isn't complicated, and that's part of its appeal. The blankets are made from white geotextile fleece - essentially synthetic fabric engineered to withstand UV radiation and Alpine weather. Their power comes from exploiting two simple principles: albedo and insulation.

Fresh snow reflects up to 90 percent of incoming solar radiation, which is why glaciers historically stayed frozen even in summer. But as climate change warms the atmosphere, darker ice and rock become exposed, absorbing more heat and accelerating melt in a vicious feedback loop. The white blankets artificially restore that reflective surface, bouncing sunlight back into space before it can add energy to the ice below.

Meanwhile, the fabric's woven structure traps air, creating an insulating barrier between the ice and warm summer temperatures. Together, these mechanisms can reduce melt by 1.5 meters of thickness annually in covered zones - a stunning achievement when you consider the alternative is watching that ice disappear into streams and rivers.

Field measurements show blankets reduce summer melt by 50-70% in covered areas - but those areas represent less than 0.2% of total Alpine glacier surface.

Field measurements at Switzerland's iconic Rhône Glacier confirm the effect. For years, workers have covered about 2 hectares of ice with UV-resistant fleece during warm months. The result? A demonstrable 50 to 70 percent reduction in summer melt over those specific patches. Walk across the covered sections in late summer, and you'll find substantially more ice than on adjacent uncovered slopes - a stark visual proof of concept.

China's glacier protection program reported similar results from experiments at Dagu Glacier No. 17 in Sichuan Province, where blankets reduced melting by the same 50 to 70 percent range. The materials have evolved from basic geotextile to advanced nanomaterial fabrics designed to maximize both reflectivity and durability. The science, in isolation, works beautifully.

The practice didn't begin as environmental conservation - it started with money. In the early 2000s, Swiss ski resorts faced a growing crisis: glaciers that once guaranteed reliable snow cover were retreating, exposing rock and dirt that destroyed ski runs. Summer glacier skiing, a lucrative draw for Alpine tourism, was literally melting away.

Resort operators experimented with covering small patches of snow and ice at lift terminals and popular runs, discovering they could preserve skiable surfaces through the summer if they protected them from the sun. What worked for a few hundred square meters of snow at Morteratsch glacier gradually expanded as climate impacts intensified and the economic case became clearer.

The technique evolved from opportunistic snow preservation into a broader climate adaptation strategy when scientists and glacier monitoring networks began documenting the accelerating loss. Projects now span multiple countries, with major implementations across Switzerland, Italy, and Austria covering hectares of glacier surface annually. China launched its Memory of Glaciers initiative, bringing national-scale resources to blanket experiments that had been largely boutique European efforts.

Yet the origin story reveals a fundamental tension: most blanket projects remain driven by ski resort economics rather than conservation mandates. The areas protected tend to be high-value tourism zones where saving ice translates directly into revenue. Environmental agencies and climate researchers are rarely the ones deploying the fabric - it's business owners protecting assets.

Here's where the fairy tale hits mathematics. Covering the Rhône Glacier's 2 hectares reduces melt significantly in that tiny fraction of ice. The glacier's total area? 17.6 square kilometers - meaning current blanket coverage protects about 0.11 percent of its surface. Across the Alps, thousands of glaciers are disintegrating simultaneously, spanning hundreds of thousands of hectares.

The cost estimates are sobering. Several hundred thousand euros per hectare per year is the going rate for blanket deployment, accounting for material, labor, seasonal installation, and removal. That might pencil out for a ski resort with guaranteed tourist revenue, but scaling to meaningful percentages of glacial coverage would require billions annually - resources that few regions or countries could justify when weighed against other climate priorities.

"While they can be effective and profitable locally, their wider use is neither feasible nor cost-effective."

- Swiss 2021 study on glacier blanketing

A Swiss study from 2021 concluded bluntly: while blankets can be effective and profitable locally, their wider use is neither feasible nor cost-effective. The numbers simply don't work beyond small, high-value patches where the economic return exceeds the installation expense.

There's also the sheer logistics. Installing blankets requires teams of workers to haul heavy fabric rolls up mountainsides, often via helicopter, then anchor thousands of square meters of material to unstable, shifting ice. Each autumn, crews must remove the blankets before winter snowfall buries them. Every spring, they repeat the process as snow melts. It's labor-intensive, weather-dependent, and becomes exponentially harder as you scale up from 2 hectares to 200 or 2,000.

Compare that effort to what would be required to blanket even a modest 10 percent of the Alps' remaining ice. You'd need coordinated helicopter fleets, hundreds of seasonal workers, industrial-scale fabric manufacturing, and an ongoing maintenance apparatus that would rival major infrastructure projects. And for what? Buying time while the underlying climate driver - rising greenhouse gas concentrations - continues forcing temperatures upward regardless of how much fabric we deploy.

Synthetic geotextiles are plastic. They shed microfibers, break down under UV exposure despite engineering efforts, and eventually degrade into the very ecosystems they're meant to protect. When you drape millions of square meters of plastic-based fabric across pristine Alpine environments, you're introducing a new variable into delicate glacial ecosystems that have evolved over millennia.

The blankets cover ice, but they also sit over rock, soil, and the thin biological crusts that exist in marginal glacial zones. They alter local hydrology by changing how meltwater flows and pools. They create artificial microclimates beneath the fabric where temperatures, humidity, and light levels differ radically from natural conditions. We don't yet have long-term studies on how these alterations cascade through alpine food webs, though some researchers warn about potential microplastic contamination of downstream waters.

There's also an aesthetic and philosophical dimension that's harder to quantify but no less real. Glaciers hold profound cultural significance across Alpine communities - they're symbols of permanence, power, natural beauty. Wrapping them in industrial fabric transforms wilderness into something managed, engineered, visibly scarred by human intervention. Some critics argue this crosses a line, turning landscapes that inspire awe into landscapes that require constant human maintenance, like covering deteriorating historic buildings in scaffolding rather than addressing the root decay.

"I hope that one day, people don't have to cover the glaciers, and they can be the way they are in nature's law."

- Wang Feiteng, glaciologist leading China's blanket experiments

Wang Feiteng, a glaciologist leading China's blanket experiments, captured the ambivalence perfectly: "I hope that one day, people don't have to cover the glaciers, and they can be the way they are in nature's law." Even the scientists pioneering the technique recognize it as a symptom of ecological crisis rather than a solution.

This is where glacier blanketing becomes less about fabric and more about humanity's relationship with climate change. Critics, including prominent glaciologists, worry that high-profile adaptation projects create dangerous illusions - suggesting we can engineer our way out of warming without confronting emissions.

Martin Siegert, a glaciologist at the University of Exeter studying large-scale ice interventions, framed the risk starkly when discussing similar geoengineering proposals: "We think that's a really dangerous message to be sending at this moment, when we absolutely need to nail down decarbonizing and do it really quickly." His concern applies directly to glacier blanketing: if the public believes scientists can "fix" glaciers with clever techniques, political will to cut emissions - the only action that addresses the root cause - may erode.

The core tension: We're deploying a technique that can save a few hectares while losing hundreds of thousands of hectares annually across the Alps.

Meanwhile, others argue adaptation isn't about replacing mitigation but buying time. If covering glaciers preserves critical water sources for downstream communities, prevents catastrophic glacial lake outburst floods, or maintains ecosystems while emissions policies slowly take effect, maybe that time is valuable enough to justify the effort and expense.

Johannes 'Hans' Oerlemans, a climate researcher, put it more bluntly: "If greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise, science won't be able to do anything." The subtext is clear: blankets, snowmaking, glacier engineering - none of it matters if we don't stabilize the climate system driving the melt. These techniques might preserve a few tourist glaciers or protect specific communities, but they can't reverse the trajectory.

The debate mirrors broader climate adaptation tensions. Should we spend billions hardening coastlines against rising seas, or pour those resources into emissions cuts and managed retreat? Should we invest in drought-resistant crops and water infrastructure, or prioritize land-use changes that prevent droughts? Adaptation and mitigation aren't opposites, but they compete for finite resources, attention, and political capital.

Glacier blanketing sits uncomfortably in that space - simultaneously demonstrating human ingenuity and human denial, offering genuine local benefits while distracting from global necessities.

Blankets aren't the only tool in the glacial preservation toolbox, and comparing approaches reveals just how limited any single tactic becomes at scale. Artificial snowfall has been tested at some Alpine sites, using snowmaking technology to add mass to glaciers during winter. It works, technically, but requires enormous amounts of water and energy - resources that are increasingly scarce and carbon-intensive to provide.

Some projects have experimented with albedo-enhancing sprays, chemicals that lighten ice surfaces to increase reflectivity without full fabric coverage. Early results suggest modest benefits, but questions about chemical impacts on ecosystems and whether the effect persists through multiple melt-freeze cycles remain unresolved.

More radical proposals involve large-scale geoengineering: pumping water onto glaciers to artificially thicken ice, building physical barriers to block warm air currents, even deploying giant underwater curtains to shield polar ice from warm ocean water. That last example, proposed for Antarctica's Thwaites Glacier, would cost an estimated $40 to $80 billion for installation plus billions annually for maintenance - figures that make Alpine blankets look quaint by comparison.

The common thread: every intervention faces the same brutal constraints of cost, scale, and the reality that climate change is a systemic problem requiring systemic solutions. Protecting one glacier, or one patch of one glacier, does nothing about the warming atmosphere and ocean that threatens all ice everywhere.

Strip away the symbolism and focus on what we can measure. The Dolomites glaciers lost approximately 56 percent of their area from the 1980s to 2023, with 33 percent of that loss occurring just in the last 13 years. That's acceleration, not stabilization. Switzerland's glacier monitoring network, GLAMOS, documented that between 2016 and 2022, about 100 glaciers disappeared entirely - not shrank, disappeared.

The Alps and Pyrenees have lost around 39 percent of their mass since 2000, contributing significantly to the 273 billion tons of ice lost globally each year from glaciers worldwide. That loss has already added 18 millimeters to global sea level rise, making glacier melt the second-largest driver of rising oceans after thermal expansion from warming water.

Between 2016 and 2022, approximately 100 Swiss glaciers disappeared entirely - not shrank, vanished completely from the landscape.

Against that backdrop, projects protecting a few hectares register as rounding errors. The Rhône Glacier, despite its blanket coverage, has still lost about 60 percent of its volume since 1850, and the melt rate is accelerating. Between 2023 and 2024, it lost 2.5 percent of its remaining mass - well above the decadal average and occurring despite the blanket deployment.

The science is unambiguous: even with local interventions, glaciers will continue retreating as long as atmospheric temperatures keep rising. Matthias Huss, director of GLAMOS, summarized the trajectory with remarkable understatement: "This is really a lot." Then he added the kicker that should frame every adaptation debate: "Even if the climate is stabilized today, they will continue retreating."

So what's the path forward when blankets can't scale and the glaciers are melting anyway? Communities across the Alps are beginning to plan for a future where ice is memory rather than resource. Water management systems designed around reliable glacial meltwater through summer droughts need redesign for a world where rivers run differently. Hydropower plants sited to capture glacial flows require new strategies. Tourism economies built on eternal snow must reinvent themselves.

Some regions are investing in water storage infrastructure to capture and save meltwater during remaining high-flow periods, banking it for dry seasons when glacial input drops. Others are diversifying energy sources to reduce dependence on glacial-fed hydropower. Alpine communities are slowly pivoting tourism from skiing to hiking, climbing, cultural heritage - experiences that don't require ice.

These adaptations acknowledge what the glacier blanket debate often obscures: the glaciers are going to go. Not everywhere, not completely, and not overnight - but the trajectory is set unless we radically alter the emissions path that's driving atmospheric warming. Local projects might save specific patches for specific purposes, buying years or decades. They won't save the glaciers as ecosystems, as cultural icons, as the reliable climate regulators they've been throughout human civilization.

The question becomes whether we spend limited resources and attention on heroic efforts to preserve fragments, or redirect that energy toward systemic changes that could stabilize the climate system itself. It's the difference between treating symptoms and curing disease, and the glaciers are symptoms of a planet out of balance.

Glacier blanketing works. Within its narrow scope, it delivers measurable results that can protect economically valuable ice and buy time for communities dependent on glacial water. The science is sound, the implementation is proven, and the local benefits are real.

But it doesn't scale. It can't scale. The economics, logistics, and environmental trade-offs prevent blankets from becoming anything more than a boutique intervention protecting tiny fractions of the world's ice. And that's the core tension: we're deploying a technique that can save a few hectares while losing hundreds of thousands, creating dramatic images of human intervention that might distract from the harder truth that only emissions cuts can actually stabilize glaciers.

Is wrapping glaciers in plastic ingenious adaptation or ecological hubris? The answer is probably both - a brilliant demonstration of human creativity applied to a problem so large that brilliance alone can't solve it. We can drape fabric over ice and measure reduced melt, proving our technical capability. But we can't drape fabric over the atmosphere, and that's where the real problem lives.

Wang Feiteng's hope - that one day we won't need to cover glaciers - points toward the only future where glaciers survive: one where we've decarbonized aggressively enough to stabilize temperatures at levels ice can tolerate. Until then, blankets remain what they've always been: a temporary cover for something fragile, buying time we haven't yet proven we'll use wisely.

The glaciers don't care whether we think the blankets are clever or futile. They only respond to temperature. And right now, despite our best fabric and engineering, the temperature keeps rising.

Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at our galaxy's center, erupts in spectacular infrared flares up to 75 times brighter than normal. Scientists using JWST, EHT, and other observatories are revealing how magnetic reconnection and orbiting hot spots drive these dramatic events.

Segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) colonize infant guts during weaning and train T-helper 17 immune cells, shaping lifelong disease resistance. Diet, antibiotics, and birth method affect this critical colonization window.

The repair economy is transforming sustainability by making products fixable instead of disposable. Right-to-repair legislation in the EU and US is forcing manufacturers to prioritize durability, while grassroots movements and innovative businesses prove repair can be profitable, reduce e-waste, and empower consumers.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

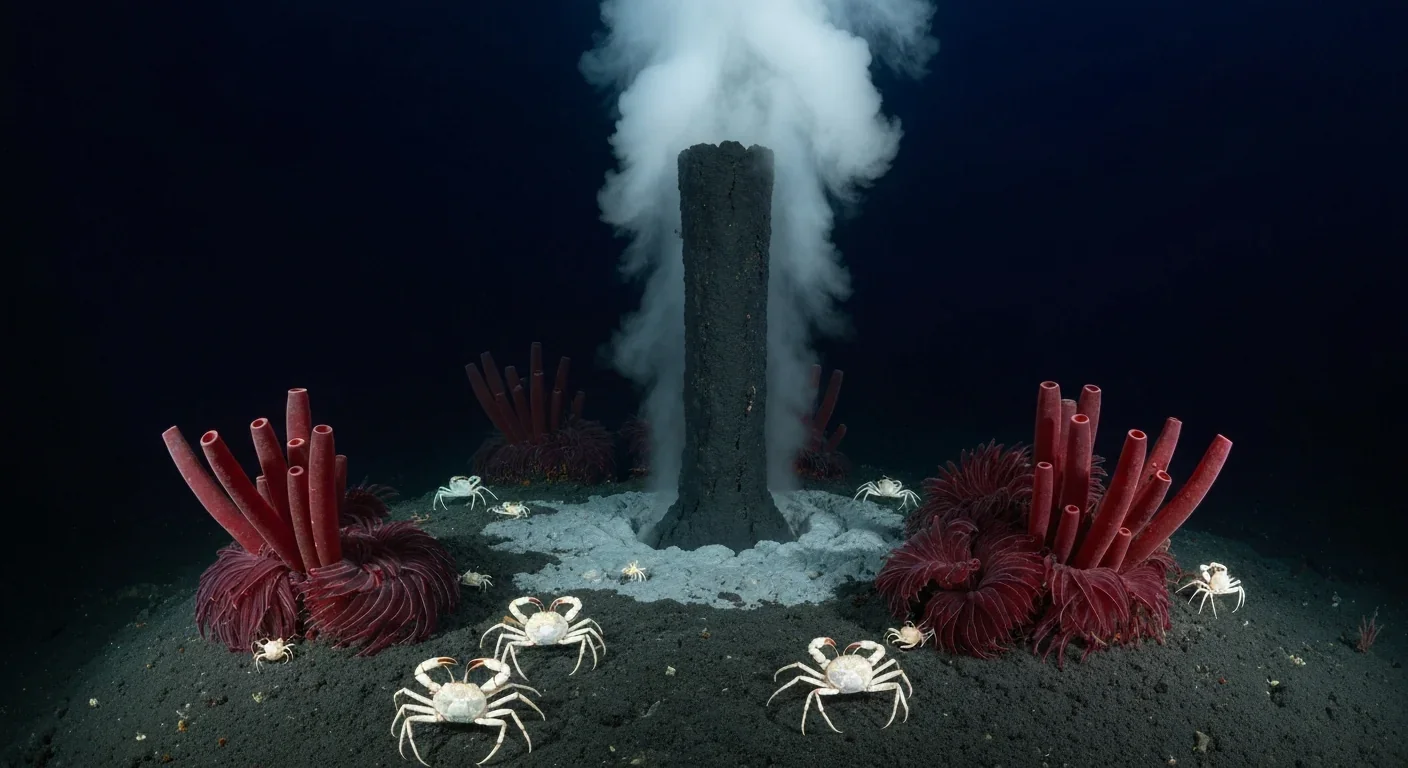

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Library socialism extends the public library model to tools, vehicles, and digital platforms through cooperatives and community ownership. Real-world examples like tool libraries, platform cooperatives, and community land trusts prove shared ownership can outperform both individual ownership and corporate platforms.

D-Wave's quantum annealing computers excel at optimization problems and are commercially deployed today, but can't perform universal quantum computation. IBM and Google's gate-based machines promise universal computing but remain too noisy for practical use. Both approaches serve different purposes, and understanding which architecture fits your problem is crucial for quantum strategy.