Can Blankets Save Glaciers? The Alpine Ice Experiment

TL;DR: The repair economy is transforming sustainability by making products fixable instead of disposable. Right-to-repair legislation in the EU and US is forcing manufacturers to prioritize durability, while grassroots movements and innovative businesses prove repair can be profitable, reduce e-waste, and empower consumers.

By 2030, the way you think about your phone, laptop, or car could fundamentally shift. Instead of planning which model to buy next, you'll be choosing which components to upgrade. Instead of tossing a broken appliance, you'll know exactly where to get it fixed and how much you'll save. This isn't speculation, it's already happening. From European Union mandates forcing manufacturers to design repairable products to grassroots repair cafés teaching neighbors to fix toasters, a quiet economic transformation is building momentum. The repair economy represents one of the most practical sustainability movements most people haven't fully grasped yet, and it's poised to reshape how we manufacture, consume, and discard nearly everything.

The numbers are staggering. By 2021, humanity generated 57.4 million tonnes of electronic waste annually, with only 17.4% properly recycled. The rest ends up in landfills or informal recycling operations where toxic substances like lead, cadmium, and beryllium leach into soil and groundwater. This isn't just an environmental crisis, it's a resource hemorrhage. Every discarded smartphone contains rare earth elements that took enormous energy to extract and refine, now sitting in a dump instead of being recovered.

The automotive sector tells a parallel story. The global automotive repair and maintenance market was valued at $779.3 billion in 2024 and is projected to reach $1.35 trillion by 2034, growing at a 5.7% compound annual rate. In the US alone, the auto repair industry generated $71.6 billion in revenue in 2023 and employs 780,000 technicians. These figures reveal something crucial: repair is already big business. What's changing is who controls it and how accessible it becomes.

By 2021, humanity generated 57.4 million tonnes of e-waste annually, with only 17.4% properly recycled. The rest leaches toxic substances into our soil and water.

But the throwaway culture extends beyond electronics and vehicles. Fast fashion garments average just seven wears before disposal. Household appliances that once lasted decades now fail within years. The deliberate design of products with artificially limited lifespans, known as planned obsolescence, has become standard business practice. When Apple admitted to slowing down older iPhones to encourage upgrades, it settled a US lawsuit for up to $500 million. The case became a flashpoint, crystallizing public frustration with products designed to fail.

The European Union has emerged as the global leader in repair rights. The EU's Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation mandates that manufacturers design products for durability, repairability, and recyclability. The 2025-2030 working plan establishes specific timelines for implementing circular design requirements across product categories. These aren't suggestions, they're enforceable standards with market access at stake.

France pioneered repairability scoring, requiring manufacturers to display repair indices on electronics and household appliances. The scores consider factors like documentation availability, ease of disassembly, and spare parts pricing. Quebec followed with Bill 29, passed in 2023, which prohibits intentional product obsolescence and promotes repairability. The law represents a fundamental challenge to planned obsolescence as a business model.

In the United States, the movement operates state by state. Right-to-repair legislation has passed in multiple states, with varying scopes. Some focus on electronics, others on agricultural equipment. The impact is already measurable: right-to-repair laws affect 70% of independent repair shops, fundamentally altering their access to diagnostic tools, schematics, and replacement parts.

The agricultural sector provides a compelling case study. Farmers challenging John Deere's control over tractor repairs became a rallying point for the movement. When a $500,000 combine harvester breaks during harvest season, farmers can't afford to wait for authorized dealers. They need immediate fixes, and right-to-repair laws are finally forcing manufacturers to provide the tools and information to make that possible.

The repair economy creates different economic value than manufacturing new products. Instead of concentrating profits in large corporations, repair distributes economic activity across independent shops, refurbishment enterprises, and community initiatives. The refurbished electronics market is experiencing explosive growth, driven by both environmental awareness and economic pragmatism. Some projections show the global refurbished electronics market nearly tripling by 2034.

Independent garages hold 55% of the automotive service provider segment and are projected to grow at a 5% annual rate. These businesses represent local employment that can't be offshored or automated easily. A repair technician diagnosing a complex mechanical failure exercises judgment and skill that machines can't replicate yet. As vehicles become more sophisticated, with electric powertrains and advanced driver assistance systems, the diagnostic expertise required actually increases, creating demand for specialized training and tools.

"The shift toward electric and autonomous vehicles is rapidly expanding the scope of diagnostics and repair services, especially in independent garages that are adapting by investing in high-voltage diagnostic tools and specialized technician training."

- GMI Insights Industry Report

For consumers, the savings are substantial. Repairing a smartphone screen costs a fraction of buying a new device. Replacing a laptop battery extends usability for years at minimal expense. Upgrading sustainably by evaluating repair versus replacement based on actual cost and environmental impact becomes economically rational when repair options are accessible and affordable.

The emergence of innovative refurbishment businesses demonstrates market demand. Companies specializing in electronics refurbishment apply rigorous quality assurance processes, offering warranties that rival new products. This expert refurbishment approach transforms used electronics from questionable purchases into viable alternatives, complete with transparent environmental impact metrics.

The environmental math is straightforward but profound. Manufacturing a new smartphone generates approximately 85% of its total carbon footprint. Using it for another year or two through repair creates a fraction of the emissions. Extending product lifespans represents one of the most efficient carbon reduction strategies available, requiring no new technology, just different business practices and consumer habits.

Beyond carbon, there's the resource dimension. Rare earth elements, precious metals, and specialized materials go into modern electronics. Mining these materials devastates landscapes and consumes enormous energy. When products designed for 10-year lifespans fail after three, we're essentially throwing away the embodied energy and materials. Repair and refurbishment keep those resources in productive use, reducing extraction pressure.

The concept of a circular economy frames repair as one component in a comprehensive system. Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) laws increasingly require manufacturers to take responsibility for products throughout their lifecycle, including end-of-life management. When combined with right-to-repair legislation, EPR creates powerful incentives for durability. If you're responsible for disposal costs, designing products that last longer and can be easily disassembled makes financial sense.

The integration of right-to-repair and EPR frameworks is emerging as a unified circular economy strategy in the US. Some states are implementing both simultaneously, creating regulatory ecosystems where repair becomes not just permitted but economically advantageous. Textile industries face similar pressures through textile EPR laws, which aim to address the waste generated by fast fashion through producer accountability.

Not everyone welcomes the repair revolution. Manufacturers built business models around predictable replacement cycles. Planned obsolescence isn't a conspiracy theory, it's a documented strategy. The Phoebus cartel in the 1920s explicitly limited lightbulb lifespans to increase sales, a practice that continues in various forms today.

Modern arguments against right-to-repair legislation center on intellectual property protection, safety concerns, and security risks. Manufacturers claim that providing repair information and parts access would expose proprietary technology to competitors and enable dangerous or ineffective repairs by unqualified technicians. These concerns aren't entirely unfounded, but critics argue they're overblown compared to the benefits of repair access.

Manufacturing a new smartphone generates 85% of its total carbon footprint. Extending its life by just one year through repair creates a fraction of the emissions.

The intellectual property versus repair rights debate presents genuine complexity. How do you protect legitimate innovation while ensuring consumers can fix what they own? The answer emerging from legislation worldwide involves balancing mechanisms: requiring repair information while protecting trade secrets, mandating parts availability while maintaining quality standards, enabling independent repair while preserving warranty protections for authorized service.

One particularly contentious issue is parts pairing, where manufacturers use software to reject replacement components not authorized by the original maker. Apple's practice of pairing screens, batteries, and other parts to specific devices means even genuine Apple components won't function properly if installed by third parties without proprietary tools. Critics call this anticompetitive; manufacturers claim it protects security and user experience.

The barriers to right to repair extend beyond manufacturer opposition. Repair infrastructure takes time to build. Technicians need training on new products. Spare parts supply chains must be established. Consumers need to shift ingrained habits of disposal. These systemic challenges mean that even with legislation in place, realizing a mature repair economy requires years of development.

While legislators debate and manufacturers resist, a grassroots repair culture has been growing for years. Repair Cafés started in Amsterdam in 2009 and have since spread globally, creating community spaces where people bring broken items and volunteers help fix them for free. The model builds repair skills while reducing waste, but it also creates something less tangible: social connection around sustainability.

These gatherings change people's relationships with their possessions. When you watch someone diagnose and fix your broken coffee maker, explaining each step, you gain confidence that repair is possible. The mystique around electronics and appliances dissolves when you see the actual components and understand how they work. This knowledge transfer represents cultural change as much as practical skill building.

iFixit has become the repair movement's information hub, publishing detailed repair guides and advocating for right-to-repair legislation. Their repairability scores for new products create market pressure, embarrassing manufacturers with low scores and rewarding those who design for repair. The site's teardowns of new devices, complete with X-ray imaging and detailed component analysis, demystify technology while documenting exactly how repairable (or unrepairable) products are.

Independent repair shops represent the commercial side of this culture. These businesses survived despite manufacturer obstacles through ingenuity, reverse engineering, and gray market parts. Right-to-repair laws vindicate their decades-long struggle for access to information and components. Many shops now expand services, offering diagnostics, upgrades, and refurbishment alongside basic repairs.

Some manufacturers are adapting rather than purely resisting. Apple's Self Service Repair program, launched in 2021, allows customers to purchase genuine parts and rent specialized tools for DIY repairs. The step-by-step guides cover common repairs like screen and battery replacement for iPhones, iPads, and Macs.

However, critics note the program has significant limitations. iFixit's analysis of Apple's self-repair vision found the process surprisingly complex and expensive compared to third-party options. Tool rental fees, parts costs, and intricate procedures mean most consumers still choose professional repair or Apple's own service. The program may represent minimum compliance with repair pressure rather than genuine commitment to user repairability.

"Repair Cafés change people's relationships with their possessions. The mystique around electronics dissolves when you see the actual components and understand how they work."

- ESRAG Environmental Sustainability Report

Fairphone presents a contrasting approach. This Dutch company designs smartphones explicitly for longevity and repairability, with modular components that users can replace without tools or technical expertise. The business model proves that repairability can be a selling point rather than a concession. Fairphone's existence demonstrates that technical barriers to repair are often design choices, not engineering necessities.

The Framework Laptop takes similar principles to computing. Modular electronics with replaceable components allow users to upgrade specific parts, like memory or storage, without replacing the entire device. The mainboard itself can be swapped, effectively creating a new laptop while preserving the screen, keyboard, and chassis. This approach challenges the assumption that electronics must be sealed, irreparable units.

These companies remain niche players, but their growing market presence proves demand exists. As refurbished tech becomes a sustainable consumer choice gaining mainstream acceptance, the pressure on major manufacturers to offer genuine repairability increases. Market dynamics may ultimately accomplish what legislation alone cannot.

Projecting forward, a mature repair economy transforms multiple aspects of consumption and manufacturing. Products carry repairability scores as standard information, influencing purchase decisions like fuel economy ratings or energy efficiency labels. Manufacturers compete on durability and ease of repair, marketing 10-year support commitments and modular upgrade paths.

Independent repair networks expand dramatically, employing millions globally in skilled technical work. Training programs and certifications standardize expertise, creating career paths in repair and refurbishment. Community repair spaces operate in every neighborhood, offering tools, expertise, and parts access. The stigma of "used" or "refurbished" products evaporates as quality assurance and warranties make them equivalent to new.

Extended Producer Responsibility frameworks mature, creating closed-loop systems where manufacturers reclaim products at end-of-life, harvest components for refurbishment, and recycle materials for new production. Design for disassembly becomes standard practice, with products using standardized fasteners, clearly labeled components, and accessible repair documentation.

The environmental impact becomes quantifiable. Carbon emissions drop as product replacement rates decrease. Resource extraction slows as materials recirculate through repair and refurbishment cycles. E-waste volumes decline as products reach their designed lifespans rather than premature obsolescence. The circular design mandates doubling resource efficiency set targets that seemed ambitious in 2025 but become achievable through systematic repair integration.

Employment patterns shift. Manufacturing jobs in some sectors decline as replacement demand drops, but repair, refurbishment, and upgrade services absorb displaced workers into more distributed, local employment. The economic value of keeping products functional over decades exceeds the short-term profits of planned obsolescence.

Consumer empowerment reaches new levels. People understand what they own, how it works, and what options exist when it breaks. The learned helplessness created by sealed, unrepairable products gives way to informed decision-making. You don't need an engineering degree to assess whether repair or replacement makes more environmental and economic sense, you just need access to information and options.

The repair revolution isn't guaranteed. Manufacturer resistance, consumer habits, and infrastructure gaps could slow or derail progress. But the momentum is undeniable. Legislation continues passing, grassroots movements keep expanding, market opportunities attract investment, and environmental necessity drives urgency.

The real question isn't whether repair culture will grow, it's how fast and how comprehensively it transforms our relationship with the things we own. Every repaired phone, every refurbished laptop, every community repair workshop represents not just waste avoided but a different economic logic taking root.

This movement connects individual choices to systemic change in unusually direct ways. When you repair instead of replace, you're voting with your wallet for a different kind of economy. When you learn to fix something, you're building skills that resilience requires. When you support legislation and businesses prioritizing repairability, you're shaping markets and incentives.

The throwaway culture of the past century was built through deliberate decisions: design choices, business models, marketing, planned obsolescence. The repair economy will be built the same way, through thousands of decisions by consumers, businesses, policymakers, and technicians. The difference is we now understand the stakes, not just environmental catastrophe avoided, but a more equitable, resilient, and sustainable way of meeting human needs.

By 2030, fixing what you own may not just be possible, it might be the most impactful thing you can do for the planet. And unlike many climate solutions, this one saves you money while building skills and community. That's a revolution worth repairing for.

Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at our galaxy's center, erupts in spectacular infrared flares up to 75 times brighter than normal. Scientists using JWST, EHT, and other observatories are revealing how magnetic reconnection and orbiting hot spots drive these dramatic events.

Segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) colonize infant guts during weaning and train T-helper 17 immune cells, shaping lifelong disease resistance. Diet, antibiotics, and birth method affect this critical colonization window.

The repair economy is transforming sustainability by making products fixable instead of disposable. Right-to-repair legislation in the EU and US is forcing manufacturers to prioritize durability, while grassroots movements and innovative businesses prove repair can be profitable, reduce e-waste, and empower consumers.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

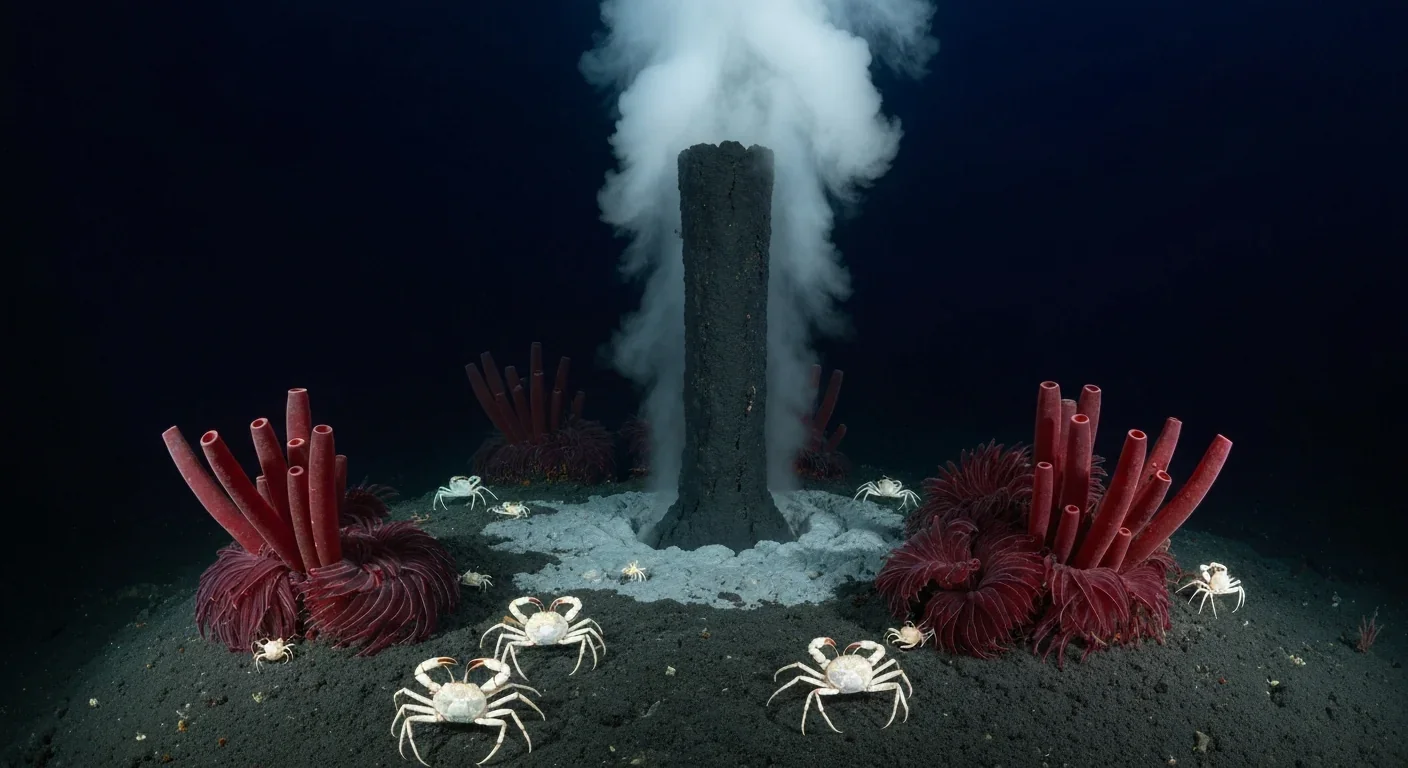

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Library socialism extends the public library model to tools, vehicles, and digital platforms through cooperatives and community ownership. Real-world examples like tool libraries, platform cooperatives, and community land trusts prove shared ownership can outperform both individual ownership and corporate platforms.

D-Wave's quantum annealing computers excel at optimization problems and are commercially deployed today, but can't perform universal quantum computation. IBM and Google's gate-based machines promise universal computing but remain too noisy for practical use. Both approaches serve different purposes, and understanding which architecture fits your problem is crucial for quantum strategy.