3D-Printed Coral Reefs: Can We Engineer Marine Recovery?

TL;DR: The degrowth movement proposes deliberate economic contraction in wealthy nations to reduce ecological damage. While experiments show promise locally, political barriers and inequality concerns make wholesale adoption unlikely, though the concept challenges growth-dependent assumptions.

By 2030, several European cities will have deliberately slowed their economies, testing a radical theory: what if we chose recession over planetary collapse? The degrowth movement is no longer just academic debate. It's becoming policy, with real governments experimenting on real people. The question isn't whether this sounds extreme. It's whether continuing business as usual sounds survivable.

Degrowth challenges capitalism's fundamental assumption that economies must grow forever. The logic is deceptively simple: infinite growth on a finite planet is mathematically impossible. Yet our entire civilization runs on this contradiction. Stock markets reward expansion, politicians campaign on GDP growth, and economists treat stagnation like a disease.

The movement emerged from French anti-capitalist thinkers in the 1970s, but recent research shows it's gaining mainstream traction. Scholars like Serge Latouche and Jason Hickel argue we're not just facing climate change but a systemic polycrisis where ecological collapse, political dysfunction, and economic instability feed each other. Their solution? Stop treating growth as sacred and start designing for wellbeing instead.

What makes degrowth different from previous environmental movements is its willingness to name the taboo. We can't innovate our way out of this, they argue, because the problem is innovation in service of endless expansion. Every efficiency gain gets swallowed by increased consumption. We produce more food while hunger persists. We build cleaner cars while driving more miles. The treadmill speeds up, and we call it progress.

Mark Burton, a leading degrowth theorist, puts it bluntly: "We do not expect to win but we cannot afford to lose." It's an unusual rallying cry for a social movement, admitting defeat before the battle. But it reflects a stark calculation. The ruling class won't voluntarily relinquish growth. Collapse may be inevitable. So degrowth becomes about building alternatives within the cracks, preparing for a better collapse rather than the catastrophic one we're careening toward.

Here's where it gets uncomfortable. Degrowth advocates propose deliberately reducing economic activity in wealthy nations. Not the chaotic recession triggered by financial crashes, but planned contraction guided by democratic priorities. Think of it as economic chemotherapy: poisoning the tumor while trying to keep the patient alive.

The OECD's latest scenarios reveal the stakes. Without rapid emissions reductions, climate damage could shrink global GDP by 36% by 2100. That's not a recession. That's civilizational unraveling. By comparison, a controlled 2-3% annual contraction in high-income economies starts looking almost conservative.

How would it work? The policy toolkit includes shorter work weeks, consumption taxes on luxury goods, investment caps on extractive industries, and wealth redistribution through universal basic income. France already experimented with the 35-hour work week. Spain is piloting a 32-hour week. These aren't full degrowth policies, but they test the core premise: can people live better with less?

The environmental logic is straightforward. GDP correlates directly with carbon emissions, resource extraction, and waste production. Cut GDP in wealthy nations by 10%, and emissions fall proportionally, assuming you don't just offshore production to poorer countries. Couple that reduction with redistribution, so shrinking the economic pie doesn't devastate the working class, and theoretically you've bought time for the energy transition.

But theory meets reality in messy ways. COVID-19 gave us an accidental degrowth experiment. Lockdowns slashed economic activity globally. Air quality improved dramatically in cities from Los Angeles to Delhi. Emissions dropped. Wildlife reclaimed urban spaces. Then economies reopened, and emissions rebounded higher than before. The experiment proved we could reduce environmental impact quickly. It also proved we had no idea how to maintain gains without authoritarian measures or mass suffering.

Despite the academic origins, degrowth is being tested in small-scale experiments worldwide. Circular economy projects in the Netherlands demonstrate how biogas and biofertilizer markets can operate on waste streams rather than virgin resources. Production still happens, but it's decoupled from extraction.

Time-banking networks in Japan and Spain let people trade services without money, creating parallel economies that don't register as GDP but generate real value. Someone fixes your bicycle, you teach their kid guitar, they help your neighbor with gardening. The economy shrinks in monetary terms while community wealth grows.

Barcelona pioneered the "superblock" model, reclaiming car-dominated streets for pedestrians. Traffic didn't disappear; it redistributed. But the change reduced consumption of gasoline, decreased pollution-related health costs, and created public space that doesn't require purchasing anything to enjoy. It's degrowth in physical form, trading automotive GDP for livability.

At the Oslo degrowth conference, activists organized a "degrowth and delinking tent" focused on Samir Amin's concept of delinking - severing dependency on global capitalism's extractive trade relationships. It's not isolationism but selective integration, choosing which global connections serve local wellbeing versus which ones funnel wealth upward and resources outward.

The European Union's circular economy initiatives have reduced landfill waste by 25% in participating regions while creating new jobs in repair, refurbishment, and recycling. It's not full degrowth, but it demonstrates that economic contraction in extractive sectors doesn't require proportional job losses if you simultaneously expand regenerative industries.

These experiments share a pattern. They work locally, improve quality of life, and reduce ecological footprint. But they struggle to scale. National governments remain wedded to growth targets. International trade agreements penalize countries that restrict extraction. And financial systems punish stagnation with capital flight. The experiments prove the concept while simultaneously revealing the political barriers.

The objections to degrowth aren't subtle. Critics argue it's political suicide, economic catastrophe, and social regression rolled into one. Let's take them seriously, because if degrowth can't answer these challenges, it remains a utopian fantasy.

First, the employment crisis. Modern economies are employment machines designed to run at full capacity. Reduce production, and people lose jobs. Degrowth scholars argue that work-sharing and universal basic income can soften the blow. Reduce everyone's hours instead of eliminating jobs. Provide income floors so consumption shifts toward needs rather than luxuries. But implementing this at scale requires political will that simply doesn't exist in most democracies.

Second, the inequality trap. Recessions always hit the poor hardest. The wealthy have assets that weather downturns. Workers have wages that evaporate when businesses contract. Aurora Despierta, a degrowth researcher, warns that ruling classes could appropriate degrowth rhetoric to justify austerity without redistribution. "Degrowth for the masses, luxury for the elite" is the nightmare scenario, where environmental rhetoric masks old-fashioned class war.

Third, the global justice problem. Wealthy nations telling developing countries to abandon growth ambitions is neocolonialism dressed in green. Research shows that while the global economy has doubled since 2000, poverty persists and planetary boundaries are breached. But for someone in rural India or Kenya, "degrowth" sounds like perpetual poverty while Americans continue consuming ten times their share.

Degrowth proponents insist the movement is only for wealthy nations that have already industrialized. Poor countries should develop, they argue, while rich countries contract to create ecological space. But global capitalism doesn't allow such neat divisions. Supply chains tangle economies together. Capital flows wherever returns are highest. A recession in Europe or North America cascades into export-dependent economies in the Global South.

Fourth, the feasibility question. Vincent Liegey notes that while the message of "no infinite growth on a finite planet is becoming intuitive," translating intuition into policy is another matter. Democratic systems require voters to choose less. That's asking turkeys to vote for Thanksgiving. Politicians who campaign on shrinking the economy don't win elections. They lose deposits.

If degrowth is to move from fringe theory to actual policy, it needs a political strategy that doesn't require mass enlightenment or ecological dictatorship. Some theorists, like Anna Gregoletto, propose a "dual strategy" combining grassroots prefigurative spaces with state intervention. Build community alternatives that demonstrate better ways of living, while simultaneously pushing for policy changes that scale those alternatives.

The state's role becomes crucial. Without strong public institutions, degrowth devolves into survivalism and local fiefdoms. But with progressive state capacity, governments can redistribute resources, coordinate reduction in harmful industries, and invest in care work, education, and ecological restoration - sectors that employ people without destroying the planet.

Universal basic income keeps appearing in degrowth proposals as the policy lynchpin. It decouples survival from employment, allowing economic contraction without mass destitution. Pilot programs in Kenya, Finland, and California show mixed results but consistent findings: people don't stop working, but they do choose work that's more meaningful even if it pays less. That shift from monetized growth to purposeful activity is exactly what degrowth envisions.

Work-time reduction is the other pillar. France's 35-hour week didn't collapse the economy. Productivity adjusted. People adapted. Extending that model to 30 or 28 hours shares available work more broadly and reduces both production and consumption. You can't buy as much if you're earning less, but if everyone's in the same situation and basic needs are met through public services, the trade-off becomes livable.

Taxation shifts from income to resource use and wealth. Tax carbon, plastic, virgin materials, and financial transactions. Use revenue to fund public services and basic income. The economic incentive structure gradually tilts from "produce more" to "waste less." Companies innovate toward durability and repairability because planned obsolescence becomes prohibitively expensive.

These policies aren't fantasy. Versions exist in various countries. What's missing is the political coalition to implement them comprehensively. Degrowth UK researchers note that anti-fascist movements, climate strikers, and solidarity networks are potential allies. But forging that coalition requires navigating sectarian left politics, convincing unions that less work isn't code for unemployment, and preventing the right from weaponizing degrowth as excuse for austerity.

Abstract policy discussions obscure the practical question: how does degrowth affect individual daily life? Imagine a modest version implemented in, say, Sweden by 2035.

You work four days a week. Thursday is your new weekend day. Your salary is 20% lower, but universal basic income covers necessities, public transit is free, and healthcare remains robust. You can't afford a new phone every year, but the old one is designed to be repairable and upgradeable. Fashion cycles slow because fast fashion is taxed into oblivion.

Air travel is rationed through carbon quotas. You get one long-haul flight every two years, so international vacations require planning. But rail networks have expanded massively, turning weekend trips across Europe into pleasant overnight journeys rather than stressful airport ordeals. Domestic tourism replaces exotic escapes, which might sound like downgrading until you discover local wonders you'd always ignored while chasing distant destinations.

Consumption shifts from goods to services and experiences. You buy fewer things but invest in community activities - evening classes, sports clubs, local theater. Neighborhoods organize tool libraries and shared workshops, so you can access a drill or sewing machine without owning one. Home sizes stabilize because housing is decommodified - you can't speculate on real estate, reducing incentive for oversized homes.

Food culture changes. Meat becomes occasional rather than staple, not from prohibition but from removing agricultural subsidies that make industrial livestock artificially cheap. Diets shift toward seasonal, regional produce. Supermarkets shrink, local markets expand. It's less convenient in some ways, but food becomes more connected to place and season, which sounds romantic but is actually just how humans ate for most of history.

The hardest adjustment is psychological. Consumer capitalism conditions us to equate more with better. Degrowth requires internalizing that enough is sufficient. That shift doesn't happen through policy alone. It emerges from culture, community, and the visceral experience that a four-day work week with intact ecosystems beats a five-day grind on a dying planet.

The OECD analysis reveals an uncomfortable truth. Energy transition itself acts as a short-term economic drag. Retiring fossil fuel infrastructure before it's depreciated, building renewable capacity, and adapting supply chains all reduce GDP in the near term. Under certain scenarios, those costs could reduce global output by 9% by 2100 - even in a successful climate transition.

So the choice isn't growth versus degrowth. It's planned degrowth versus climate-imposed collapse. The former is a policy choice we can design to protect vulnerable populations. The latter is ecological realities imposing non-negotiable constraints regardless of our preferences. Crop failures don't care about GDP targets. Heat waves don't respect property rights.

Degrowth advocates argue we've already entered the age of involuntary contraction. Climate disasters destroy capital. Supply chain disruptions reduce efficiency. Resource scarcity drives inflation. We're experiencing economic volatility that looks suspiciously like early-stage collapse, but we keep pretending it's temporary disruption in an otherwise functional growth model.

The movement's provocation is to stop pretending. Accept that perpetual growth has ended. Now design the landing. That means redistributing shrinking resources more equitably, investing in resilience rather than expansion, and redefining prosperity as collective wellbeing rather than individual accumulation.

Critics call this defeatist. Degrowth theorists call it realistic. The debate may be moot. As global economic growth shows, doubling the economy didn't solve poverty and did breach planetary boundaries. We tried growth-led climate solutions for thirty years. Emissions kept rising. Perhaps the experiment failed.

If a country decided to pursue degrowth seriously, what would the roadmap look like? Based on existing research and experiments, here's a plausible pathway:

Phase One: Foundation (Years 1-3)

Implement four-day work week with proportional pay reduction but enhanced public services. Launch universal basic income at poverty-line level. Shift taxes from income to carbon, resource extraction, and wealth. Invest heavily in public transit, housing, and renewable energy. These changes are economically neutral or mildly contractionary but establish safety nets before deeper cuts.

Phase Two: Restructuring (Years 4-7)

Cap extraction industries and phase out fossil fuel subsidies. Mandate repairability and durability standards for consumer goods, effectively killing planned obsolescence. Implement progressive consumption taxes that make luxury spending prohibitive while keeping necessities affordable. Reduce work weeks to 30 hours. Expand free public services to include education, healthcare, childcare, and elderly care. GDP begins contracting 2-3% annually, but social indicators improve.

Phase Three: Stabilization (Years 8-15)

Economy reaches steady state at approximately 70% of original GDP. Emissions have fallen by 50%. Material footprint reduced by 40%. Inequality metrics improve as wealth redistribution takes effect. Cultural shift toward sufficiency rather than affluence becomes normalized. New industries in repair, restoration, care work, and local production employ people displaced from extractive sectors.

This timeline assumes democratic support, which is the plan's Achilles heel. Realistically, degrowth would likely emerge piecemeal through crisis-driven necessity rather than coordinated strategy. A major climate disaster triggers emergency measures. A financial crash discredits growth ideology. Political upheaval creates openings for radical policy. Degrowth becomes the default not because we chose it, but because alternatives collapsed.

The movement's challenge is preparing those alternatives so they're ready when crisis arrives. Prefigurative experiments, theoretical frameworks, and policy blueprints all serve as seeds that might germinate when conditions shift. Burton's resigned optimism - "we do not expect to win but cannot afford to lose" - reflects this long-game perspective.

For all its intellectual rigor, degrowth still hasn't solved fundamental tensions. How do you prevent wealthy individuals from hoarding resources while the collective degrows? Can democracies really vote for less, or does degrowth require some form of eco-authoritarianism? If rich countries degrow while developing nations continue industrializing, does that just shift production and emissions rather than reducing them globally?

The movement also struggles with diversity of perspectives. Critics note the absence of feminist, queer, and decolonial voices in mainstream degrowth discourse. If the theory emerges primarily from European academics, how does it avoid replicating colonial patterns where the Global North dictates development pathways for the South?

There's also the stubborn reality that human ingenuity has repeatedly broken through apparent limits. Malthus predicted famine when populations outstripped agriculture. The Green Revolution proved him wrong. Peak oil was supposed to collapse civilization in the 1970s. Fracking and renewables changed the equation. What if the next decade brings fusion power, carbon capture at scale, or some other breakthrough that makes degrowth unnecessary?

Degrowth theorists argue that betting civilization's survival on hypothetical future tech is reckless. Better to plan for scarcity and be pleasantly surprised by abundance than the reverse. But that conservative approach fights against centuries of progress ideology and modernist faith in human problem-solving.

So can a controlled recession save the planet? The evidence suggests it could reduce ecological damage significantly if implemented thoughtfully in high-income nations. The barriers aren't technical but political and cultural. We know how to consume less, work less, and distribute more equitably. We don't know how to convince majorities to vote for it or organize economies around it without triggering backlash.

Degrowth's value may lie less in its likelihood of being adopted wholesale and more in its role as a compass. It points toward the direction we need to move even if we never reach the destination. Every policy that shortens work weeks, expands public services, or caps resource extraction is a small step on the degrowth path, even if politicians don't call it that.

The movement also serves as necessary counterweight to techno-optimism and green growth fantasies. It forces hard questions about whether we can truly decouple economic activity from ecological destruction at the speed and scale required. So far, the data says no. Every country that has reduced emissions while growing GDP either offshored dirty industries or experienced modest, temporary declines insufficient to meet climate targets.

The degrowth challenge to conventional thinking is simple but profound: prove that perpetual growth is compatible with planetary boundaries, or admit we need a different model. Three decades of climate negotiations haven't produced that proof. Maybe it doesn't exist.

Whether degrowth wins political victories or remains a radical fringe, the conversation it forces matters. We're heading for economic contraction one way or another - either chosen and managed, or imposed and catastrophic. The difference between those futures is everything. Degrowth offers a map for the former. We can dismiss it as utopian, but we better have an alternative ready when the current system hits its hard ecological limits.

The clock isn't just ticking. It's running out. And the degrowth movement's most valuable contribution might simply be this: it takes collapse seriously enough to plan for something better on the other side.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

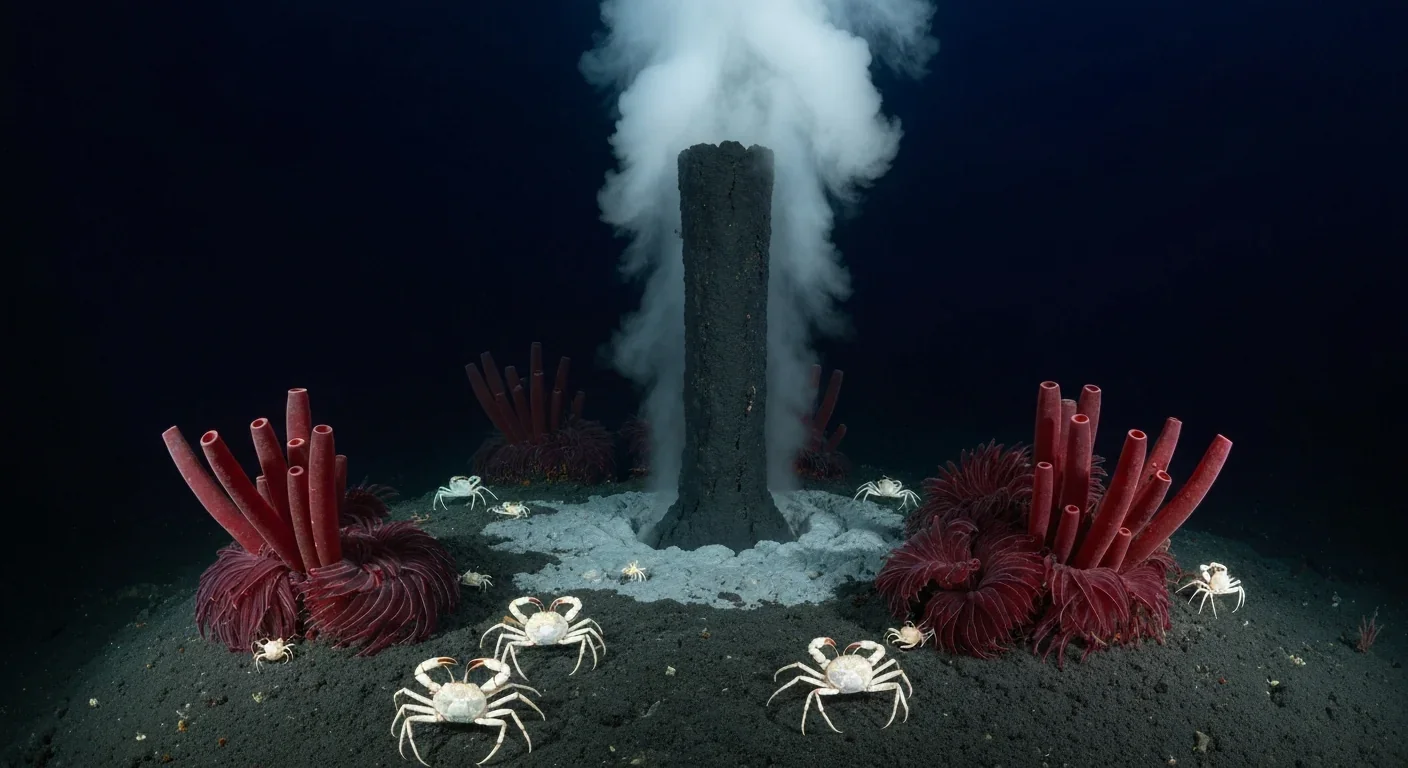

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

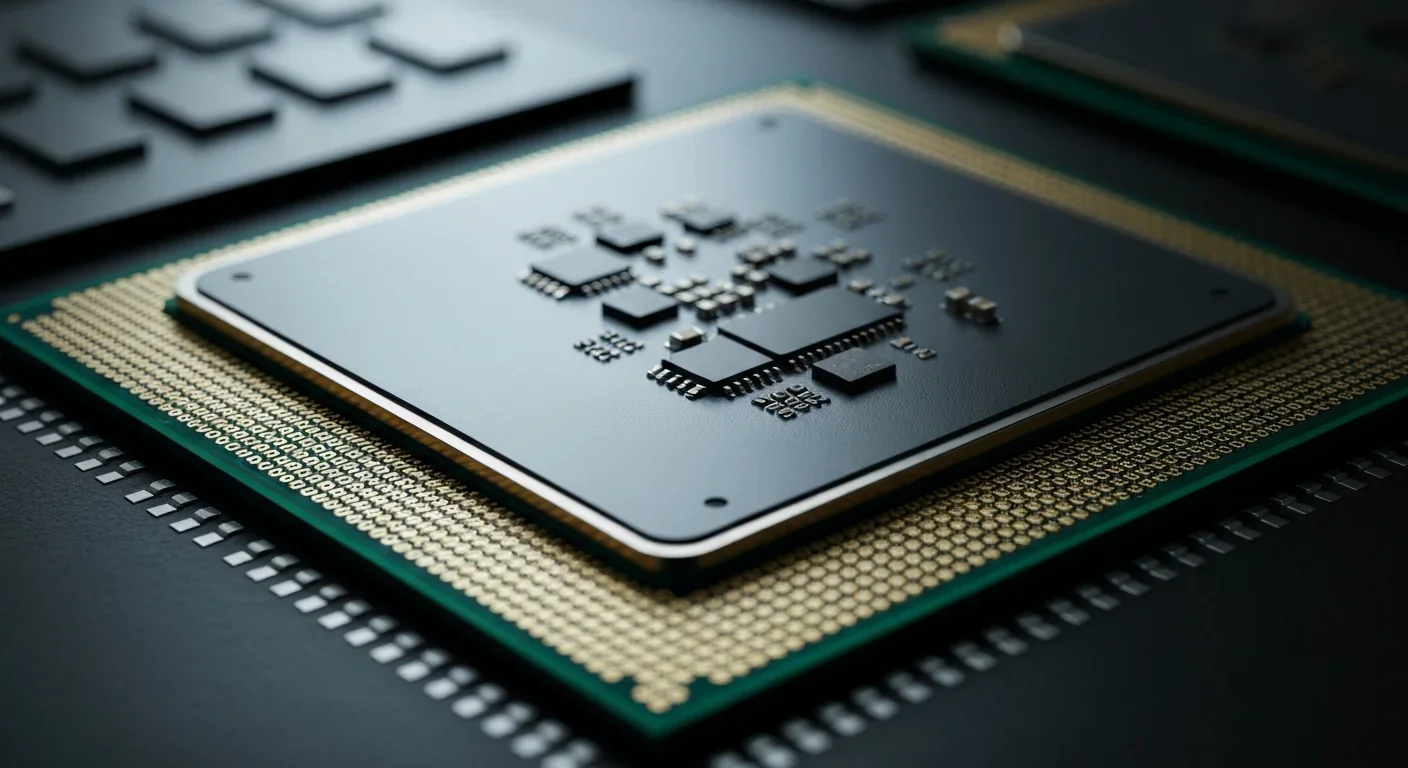

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.