3D-Printed Coral Reefs: Can We Engineer Marine Recovery?

TL;DR: Fashion rental platforms are transforming clothing consumption by making single-wear garments both economically viable and environmentally sensible. This comprehensive analysis examines their business models, environmental impact, consumer psychology, and scalability potential.

Every second, a garbage truck full of textiles gets landfilled or incinerated. Not every hour. Not every minute. Every single second. The fashion industry generates this staggering waste because most garments live short, lonely lives - worn a handful of times before exile to the back of closets or straight to landfills. But what if that designer dress you wore once to a wedding could have 30 more lives? What if the blazer gathering dust in your wardrobe could earn its environmental cost through circulation rather than stillness?

Fashion rental platforms aren't just changing how we access clothes. They're rewriting the entire value equation of ownership versus use. By 2030, circular fashion business models - including rental, resale, and repair - could unlock a $700 billion opportunity in a market drowning in its own excess. The question isn't whether rental makes sense anymore. It's whether traditional ownership can justify itself against a model that delivers fashion's pleasure without its planetary price tag.

For decades, clothing rental meant tuxedo shops and prom dress boutiques - niche services for one-off occasions. Then Rent the Runway arrived in 2009 with a radical premise: designer fashion could become a service, not a product. Access over ownership. Circulation over storage.

The numbers now vindicate that bet. The global apparel rental market hit somewhere between $2.24 and $6.2 billion in 2023, growing at roughly 7% annually. Rent the Runway forecasts double-digit subscriber growth, planning to expand inventory 134% and launch over 90 new brands. Urban Outfitters' rental arm Nuuly saw subscription sales jump 55.6% to $112.5 million in a single quarter, posting its first annual operating profit of $13 million.

Profitability in fashion rental comes from subscription recurrence, not one-off transactions. A garment that sells once for $200 can generate that amount multiple times through circulation.

Profitability stems from subscription recurrence rather than one-off rentals. Nuuly's model thrives because subscribers keep coming back, transforming what retailers call "dead inventory" into continuously monetized assets. A garment that might sell once for $200 can generate that amount several times over through repeated rentals, especially if it enters circulation during peak demand windows.

The peer-to-peer model takes this further by eliminating inventory costs entirely. Pickle, a rental marketplace, raised $12 million after capturing 25% of women aged 18-35 in Manhattan. Their platform lets individuals monetize their own closets, turning personal wardrobes into distributed rental fleets. No warehouses. No bulk purchasing. Just people sharing what already exists.

For consumers, the math is straightforward. Renting a $2,000 gown for $150 beats buying it for one wedding. But subscription models change the calculation from cost-per-wear to access-per-month. A $98 monthly subscription might deliver three outfits that would cost $600 to purchase - and you can swap them endlessly. The value proposition shifts from "do I need this item?" to "do I want perpetual wardrobe refresh?"

Rental platforms love to tout sustainability credentials. Rent the Runway claims its model has displaced 1.6 million new garment productions since 2010, with lifecycle assessments showing 24% water reduction, 6% energy reduction, and 3% CO2 reduction per rental versus purchase.

Extending garment life by nine months can slash carbon footprints by 33% and water and waste footprints by 22%. Every time a dress circulates instead of sitting idle, its production impact gets amortized across more wearers. One item doing the work of thirty means twenty-nine fewer manufacturing cycles - fewer dyes, fewer factories, fewer shipments from production facilities.

But the environmental story isn't simple. Dry cleaning, used by major platforms, consumes three to six times the energy of conventional washing. Each rental requires protective plastic wrapping and hangers, generating persistent packaging waste even when platforms switch to reusable mailers. The British Fashion Council estimates that returns from rental garments generate 350,000 metric tons of carbon emissions - equivalent to Samoa's entire annual output.

"Last-mile deliveries could prompt a 32% jump in carbon emissions by 2030 due to increased consumer expectations for both at-home convenience and speedy delivery."

- Accenture Sustainable Last Mile Report

Last-mile delivery poses the biggest challenge. Accenture research suggests such deliveries could drive a 32% jump in carbon emissions by 2030 as consumers demand faster, more convenient service. A rental model optimized for convenience - next-day delivery, unlimited swaps - can actually increase environmental impact compared to occasional retail trips.

Location matters enormously. Walking, biking, or using public transit to a local pickup point can reduce transportation impact by 85% and overall rental impact by 15%. Platforms experimenting with electric vehicle fleets and consolidated delivery routes show promise, but scaling these approaches remains challenging.

Then there's the rebound effect. Research from EDHEC and UCL Louvain found that rental can "encourage counterproductive behaviors." Some consumer segments - particularly those motivated by novelty and stimulation - use rental to increase overall consumption rather than replace purchases. They rent and buy, treating rental as fashion exploration that fuels additional spending.

The environmental case for rental rests on two assumptions: high circulation rates and genuine displacement of new purchases. When platforms achieve both, the math works. When they don't, rental becomes an addition to consumption rather than a substitution for it.

Fashion serves psychological needs beyond function. Clothing signals identity, marks occasions, builds confidence, and participates in social rituals. Rental challenges deep assumptions about ownership, personal hygiene, and the meaning of "mine."

Research using the Stimulus-Organism-Response framework reveals that rental adoption depends on emotional states - enjoyment, trust, perceived value - more than rational cost-benefit calculations. People need to feel good about renting, not just understand its logic.

Hygiene concerns remain the most visceral barrier. Transparent sanitation workflows differentiate platforms competing for trust. Some advertise ISO 14001 certification or ozone sanitization. Others provide detailed documentation of cleaning protocols. The rental industry's resilience to hygiene concerns depends less on the actual cleanliness - which is typically hospital-grade - than on visible assurance that cleanliness is taken seriously.

Size and fit present technical challenges with psychological consequences. Virtual try-on technology and AI-driven sizing recommendations directly impact return rates and customer satisfaction. When items fit well on first delivery, rental feels magical. When they don't, it feels like failure - compounded by the hassle of returns.

Demographics show predictable patterns. North America leads with 39% market share, concentrated among urban professionals aged 25-45. These consumers value variety and novelty, seek sustainable options, and have occasion-based needs (work events, social functions) that don't justify permanent wardrobe expansion. They're digitally native, comfortable with subscription models, and 72% explicitly cite environmental concerns as motivating rental choices.

For Gen Z, non-ownership signals savviness rather than deprivation. They've grown up with Spotify and Netflix - fashion rental feels like a natural extension rather than a compromise.

Gen Z approaches rental differently from millennials. For younger consumers, non-ownership signals savviness rather than deprivation. They've grown up with Spotify and Netflix, where access trumps ownership. Fashion rental feels like natural extension rather than compromise. The psychological friction isn't "why would I rent clothes?" but rather "why would I own clothes I rarely wear?"

Making rental work at scale requires solving problems that don't exist in traditional retail. Inventory must circulate constantly. Quality control needs to catch damage after every use. Cleaning must be efficient yet thorough. Logistics must minimize cost and environmental impact while delivering convenience.

Advanced warehouse management systems combined with RFID tracking create visibility from receipt to dispatch. Every garment becomes a tracked unit with usage history, condition assessments, and predictive maintenance scheduling. The technology enables platforms to know not just where items are, but which ones are approaching retirement and which styles drive repeated requests.

Circular design principles - high cotton content, removable components, durable construction - directly enhance rental feasibility by simplifying cleaning and extending viable circulation periods. Rental-optimized garments use materials that withstand repeated professional cleaning without degradation. Removable embellishments allow customization while enabling thorough sanitation. Reinforced stress points delay the wear patterns that eventually force retirement.

Rent the Runway's strategy includes back-in-stock notifications and personalized styling concierges that transform logistics challenges into engagement opportunities. When your desired item isn't available, the notification system becomes a future promise rather than a disappointment. When your taste profile is understood, recommendations feel curated rather than algorithmic.

The logistics burden explains why profitability has been elusive for many platforms. Operating margins get squeezed by cleaning costs, shipping expenses, damage rates, and the capital tied up in inventory. Platforms solving these challenges often do so through vertical integration - controlling the entire chain from acquisition through end-of-life disposal - and through technology that optimizes circulation patterns to maximize wears per garment before retirement.

Rental promises circularity, but what happens when garments can't circulate anymore? After dozens of wears, even durable items reach retirement. Do they get recycled? Resold? Landfilled?

True circular models follow Ellen MacArthur Foundation principles: eliminate waste, circulate products, regenerate nature. In fashion rental, this means designing for disassembly, using recyclable materials, and creating reverse logistics for end-of-life processing.

Some platforms partner with textile recycling facilities that shred retired garments into fiber for insulation or new fabric. Others sell damaged inventory at steep discounts, extending life through continued use even if items no longer meet rental standards. The most sophisticated approach integrates material flow tracking, ensuring every retired item has a documented destination beyond landfill.

"Only 12% of fashion companies disclose annual production volumes, and even fewer track end-of-life outcomes for rental inventory."

- Business Waste Textile Facts Report

But transparency remains limited. Only 12% of fashion companies disclose annual production volumes, and even fewer track end-of-life outcomes for rental inventory. The industry needs standardized metrics and third-party verification to distinguish genuine circularity from circular marketing.

The Ellen MacArthur Foundation's Fashion ReModel project, backed by $15 million from H&M Foundation, aims to establish common definitions and principles for circular models. Without industry-wide standards, "circular" risks becoming another greenwashing buzzword - a claim without accountability.

Luxury brands initially viewed rental as brand dilution. If anyone could access Dior for $100, would people still pay $10,000 to own it? But perspectives are shifting as brands recognize rental as customer acquisition rather than cannibalization.

Some luxury houses now run in-house rental services, maintaining control over brand experience while gathering data on consumer preferences and usage patterns. This direct relationship reveals which styles get requested most, informing future design decisions based on actual wearing patterns rather than purchase intent.

Third-party platforms provide market access without brand infrastructure investment. Designers can test demand for new lines through rental before committing to production volume. Limited runs circulate through rental networks, creating exposure that drives eventual purchases among consumers who've tested the fit and feel.

The fast fashion sector faces different dynamics. For brands like H&M and Zara, rental represents both threat and opportunity. The market shift toward rental, resale, and repair could eventually reduce new clothing sales, particularly for trend-driven items with short relevance windows. But these brands also have scale to support rental infrastructure and established customer relationships to transition toward service models.

Fashion accounts for at least one-third of global carbon emissions, with textile waste filling 7% of landfill space worldwide. Governments are noticing. The European Parliament has pushed for extended producer responsibility, requiring brands to fund end-of-life textile processing. France has banned destruction of unsold clothing. The UK is considering tax incentives for rental and repair businesses.

Regulatory support could take multiple forms: tax breaks for circular business models, subsidies for rental infrastructure, mandatory take-back schemes, or carbon pricing that makes single-use ownership economically irrational. Environmental regulations increasingly favor models that extend garment life and reduce waste.

The most effective policy approach combines carrots and sticks - incentivizing circular models while increasing costs for linear fashion production and waste.

But policy risks exist. Poorly designed regulations could favor large platforms over peer-to-peer models, or impose compliance burdens that raise barriers to entry. Definitions matter: What qualifies as "circular"? How is environmental impact measured? Can rental platforms claim emissions reductions without tracking rebound effects?

The most effective policy approach likely combines carrots and sticks - incentivizing circular models while increasing costs for linear ones. If fast fashion faced taxes proportional to its waste generation, and rental services received subsidies proportional to garments displaced, market dynamics would shift decisively toward circulation.

Can rental scale from niche to mainstream? The trajectory looks promising but not inevitable. Several conditions need to align:

Technology must improve. Virtual fitting needs to work flawlessly. Logistics must become dramatically more efficient. Cleaning protocols need to balance thoroughness with environmental impact. AI-driven styling must predict preferences accurately enough that subscribers always find desirable options available.

Consumer psychology must evolve. Ownership remains deeply embedded in identity formation and social signaling. Rental will need to offer not just equivalent value but superior experience - more variety, better quality, enhanced discovery - to overcome ownership's psychological gravitational pull.

Economics must prove durable. Current profitability for leaders like Nuuly suggests the model works, but many platforms have struggled with unit economics. Sustainable margins require high circulation rates, low damage rates, efficient logistics, and strong subscriber retention. Not every operator will thread that needle.

Environmental claims must be verified. As rental grows, scrutiny will intensify. Lifecycle assessments need third-party validation. End-of-life tracking must become standard. Rebound effects require honest measurement. Greenwashing will eventually face consequences.

Infrastructure needs investment. The rental sector needs local hubs, efficient reverse logistics, and cleaning facilities that use eco-friendly methods. This requires capital and coordination that current fragmentation doesn't support.

The most transformative possibility isn't that rental replaces ownership, but that it changes what ownership means. Imagine closets where half the items are owned and half are perpetually rotating rentals. Purchases become selective investments in pieces you'll wear repeatedly, while rental fills seasonal needs, trend exploration, and occasion-based gaps. The two models coexist, each optimized for different use cases.

By 2030, rental fashion could represent a significant fraction of the $700 billion circular fashion opportunity. Or it could remain a niche serving urban professionals and special occasions. The difference depends on whether platforms can solve the logistics puzzle, whether consumers embrace access over ownership at scale, and whether environmental benefits prove genuine rather than theoretical.

Every garment tells two stories. One is about style, identity, and the joy of wearing something that makes you feel like your best self. The other is about resources consumed, waste generated, and the planetary account ledger that fashion has overdrawn for decades.

Rental doesn't eliminate fashion's environmental burden. But it changes the denominator in the equation - spreading production impact across many wearers instead of one. When that dress you wore to three events gets worn to ninety events across thirty people, the carbon per wear drops dramatically. When your closet contains curated essentials you love plus rotating rentals for variety, you've effectively expanded your wardrobe while shrinking its footprint.

The rental revolution isn't really about clothing. It's about reimagining value in an age of abundance, asking whether access can replace ownership without sacrificing pleasure, and testing whether circular models can scale in an economic system built for linear consumption.

Fashion rental makes single-wear sensible by making multiple wears inevitable. The question isn't whether rental works - the market is proving it does. The question is whether it can scale fast enough to matter, and whether "better than buying new" is good enough when the planet needs "good enough" to mean genuinely regenerative.

Your closet is full of clothes you rarely wear. So is everyone else's. Maybe the revolution isn't finding new things to buy. Maybe it's finally using what already exists.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

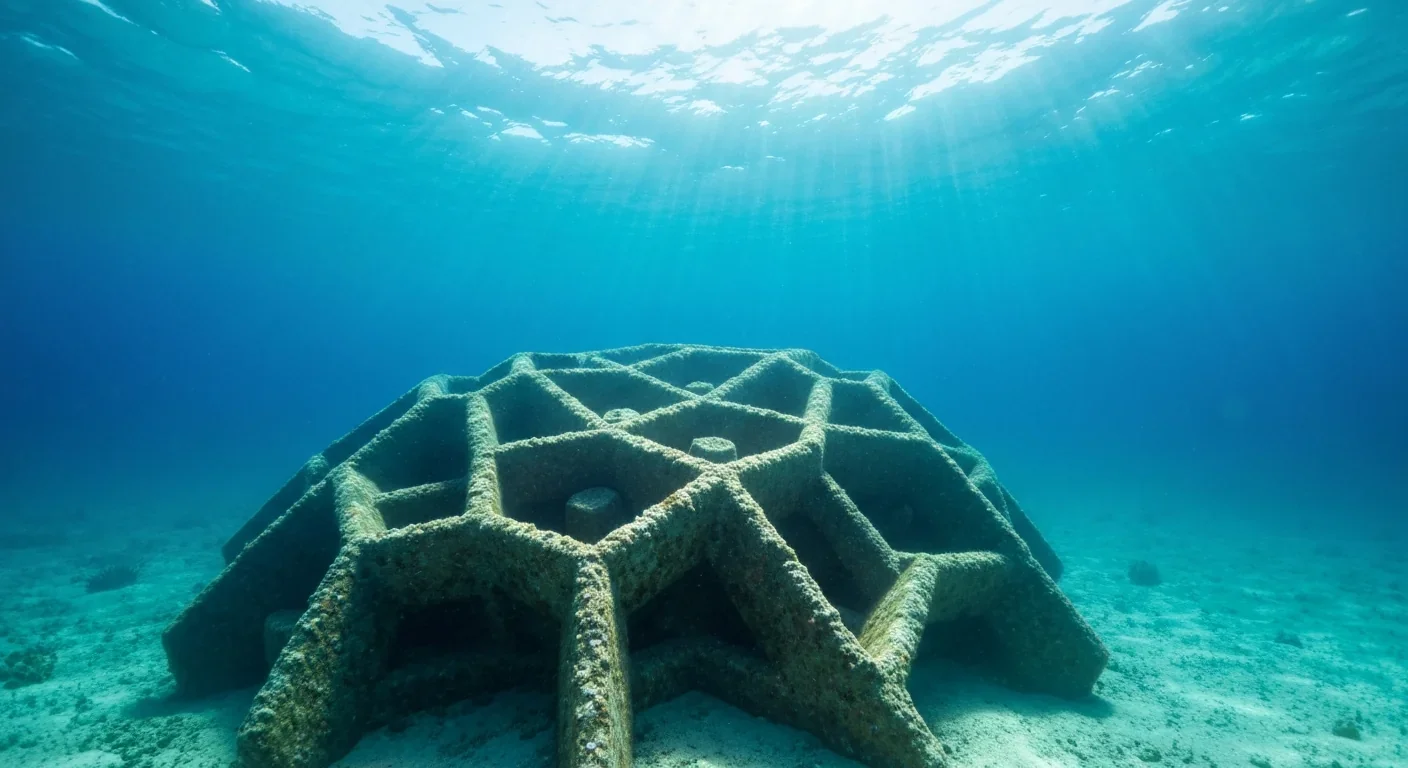

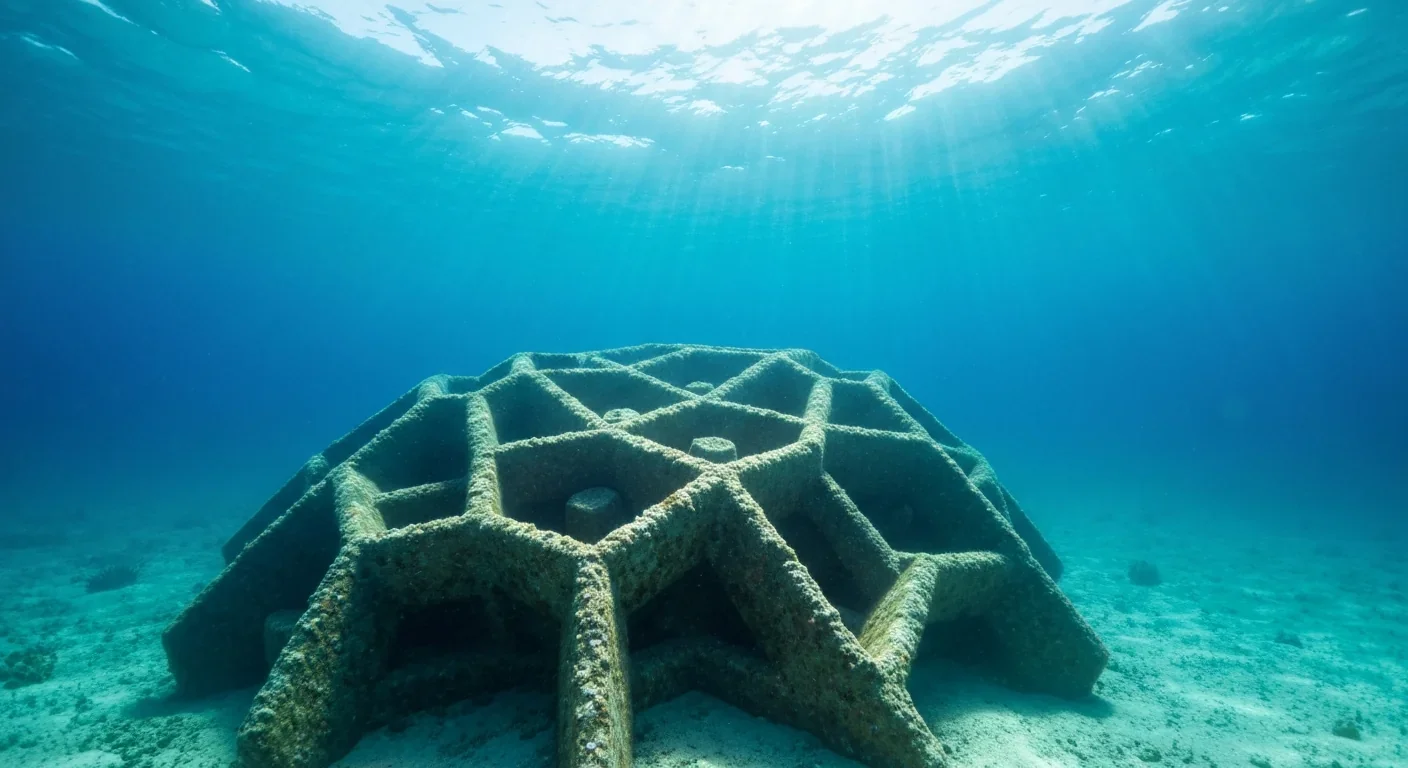

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

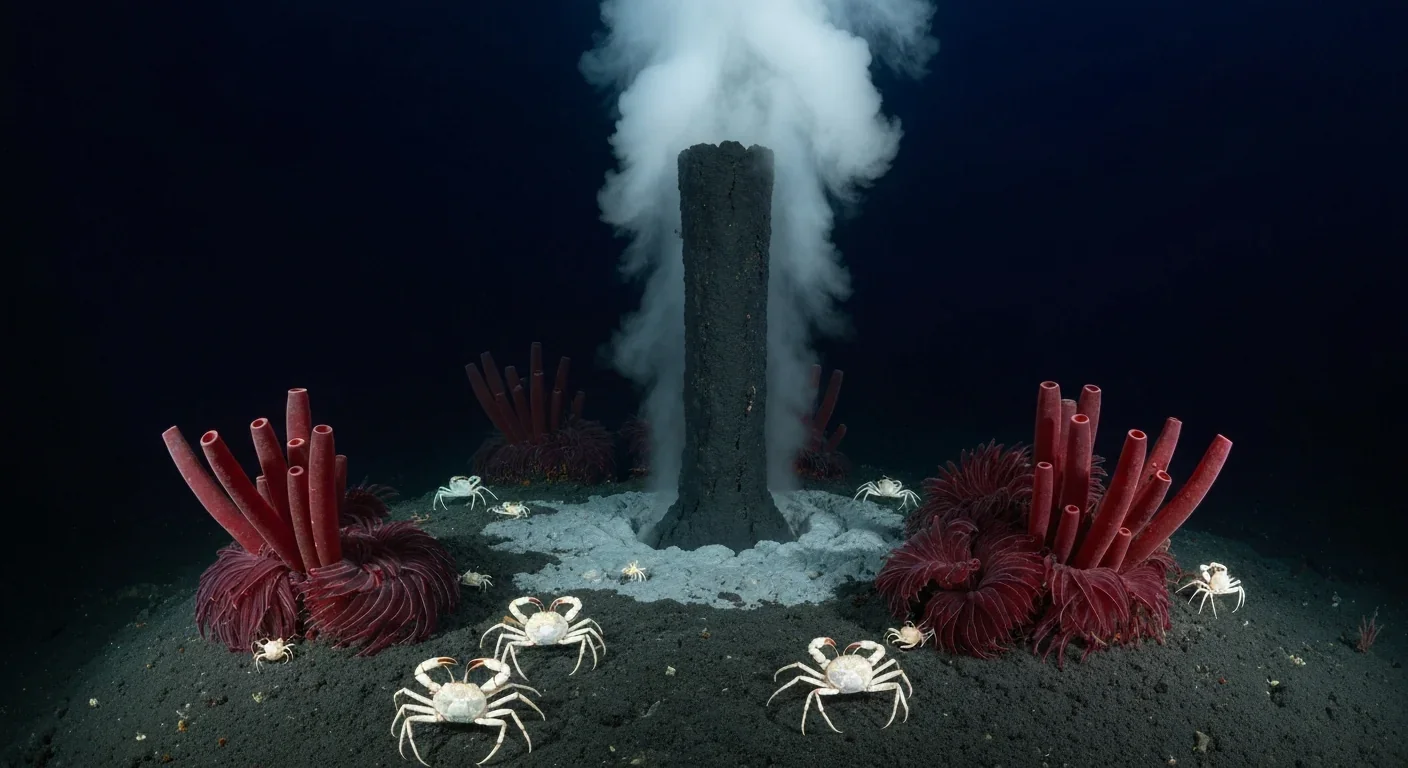

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

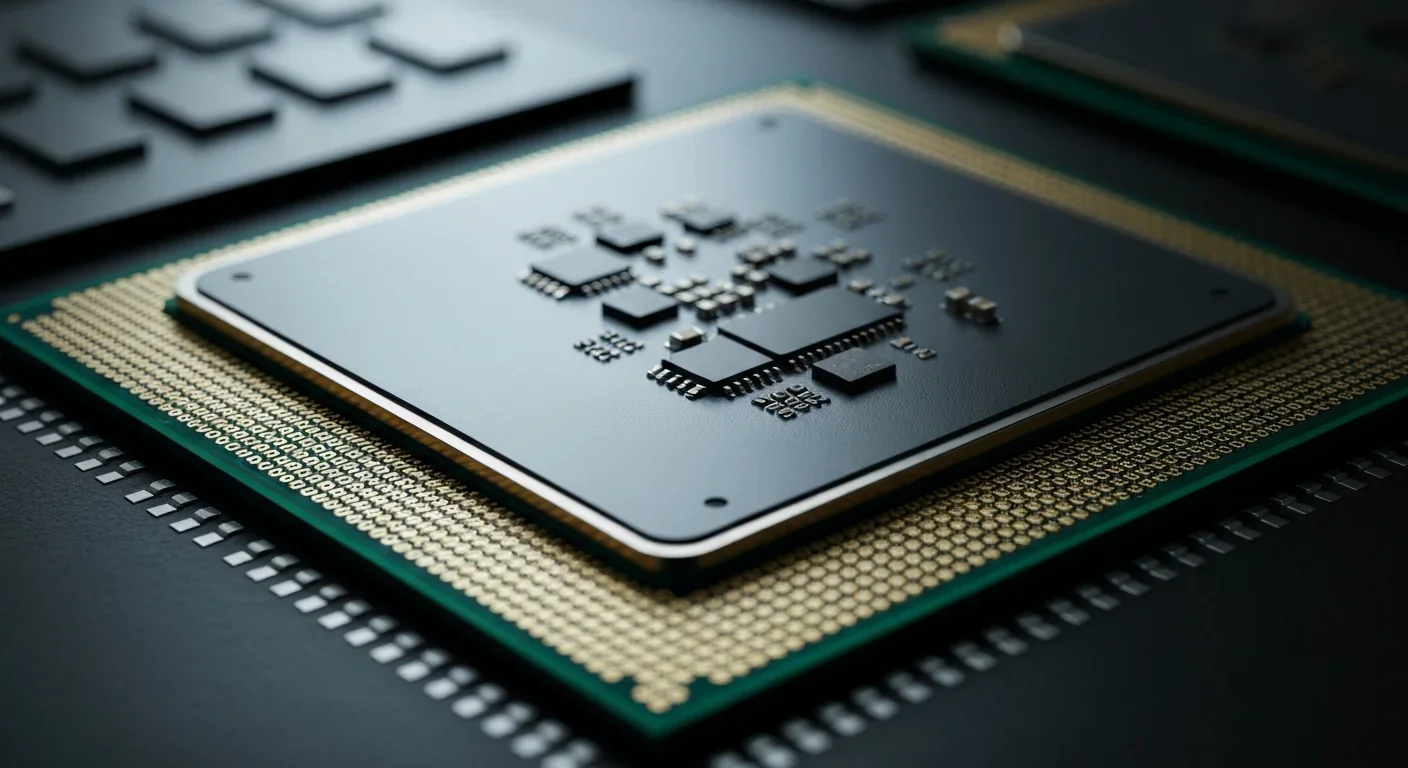

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.