The Repair Revolution: Why Fixing Things Saves the Planet

TL;DR: 3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

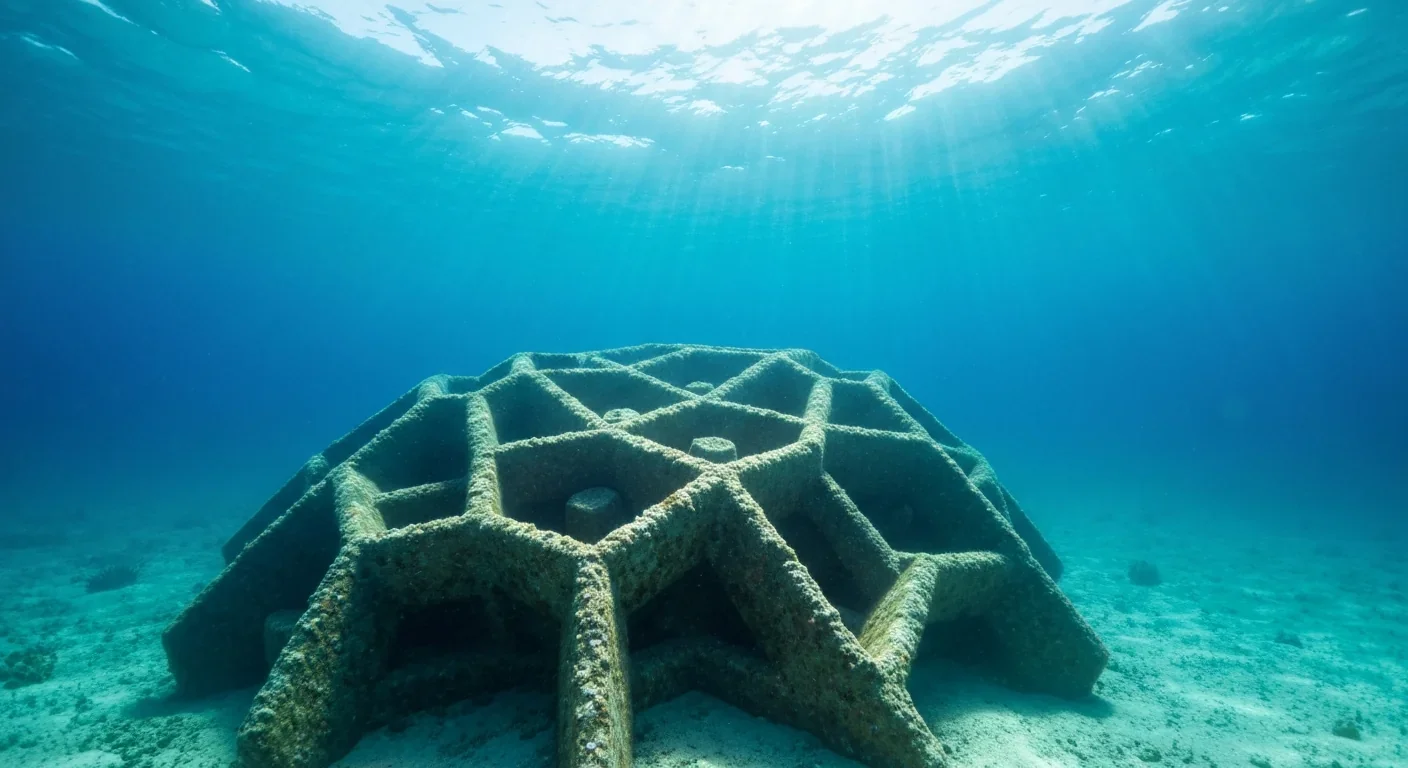

A team in Denmark just learned something expensive: baby corals are picky. Really picky. Their 3D-printed "wedding cake" structures, meticulously engineered from 70% sand and 30% pozzolanic cement, deployed with great ceremony into the Kattegat strait, sat mostly empty for months while natural reef fragments nearby teemed with new life.

The culprit? Surface chemistry at the molecular level.

It turns out that building a better reef is less about grand architectural statements and more about understanding what a millimeter-long larva can sense with its primitive nervous system. And that's forcing marine engineers to rethink everything from concrete formulas to printer nozzle designs.

Welcome to the strange intersection of computational design, marine biology, and industrial 3D printing, where scientists are racing to reverse-engineer one of nature's most complex construction projects before climate change makes the whole effort moot.

Half of the world's coral reefs have vanished since the 1950s. At 1.5°C of warming, 70-90% of what remains will die. Ocean acidification is turning seawater hostile to the calcium carbonate skeletons that corals build. Warming waters trigger bleaching events that leave vast underwater graveyards.

Traditional conservation approaches can't scale fast enough. Marine protected areas help, but they can't stop global warming. Coral gardening works, but growing fragments in nurseries and transplanting them by hand is labor-intensive and expensive. You need tens of thousands of volunteer dive hours to restore a single hectare.

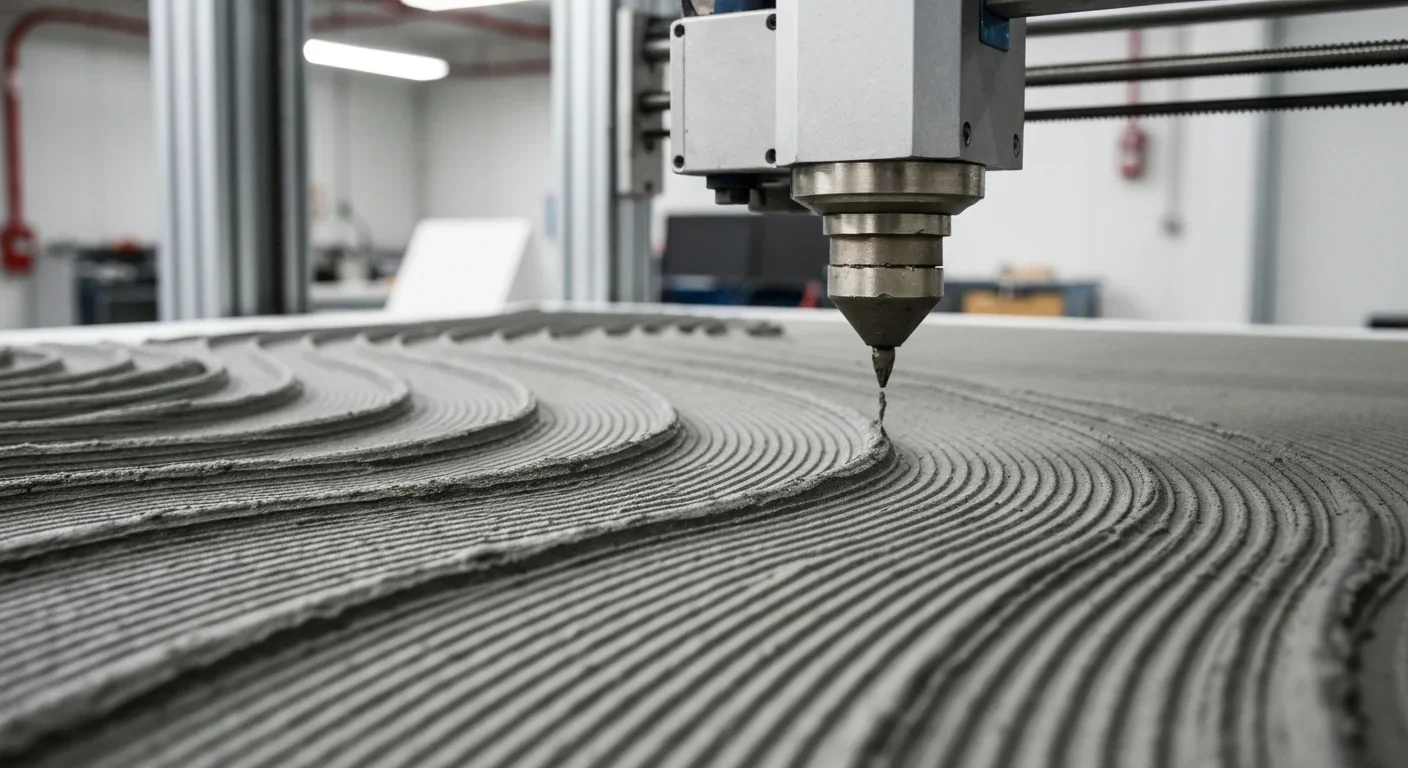

Enter the engineers with their Delta WASP 3MT CONCRETE printers and algorithmic design software, promising to manufacture coral habitat at industrial speed. It sounds like Silicon Valley solving nature, and initially, many marine biologists rolled their eyes.

But then the data started coming in.

At current warming rates, 70-90% of remaining coral reefs could vanish by mid-century. Traditional restoration methods cannot scale fast enough to counter this loss.

Understanding why 3D-printed reefs work, or don't, requires understanding the settlement phase in a coral's life cycle. For a few days after spawning, coral larvae drift as free-swimming planulae, carried by currents until chemical and physical cues tell them it's time to settle.

This moment is everything. Choose wrong and the larva dies within days, eaten by fish or smothered by algae. Choose right and it transforms into a polyp, begins laying down calcium carbonate, and starts a colony that could live for centuries.

So what makes a surface attractive?

Researchers at the University of Hawai'i tested various geometries and found that small spiral-shaped shelters, printed in ceramic, increased baby coral settlement 80 times compared to flat surfaces. Survival rates over a year improved 50-fold.

The secret was mimicking natural crevices, those tiny protected spaces where larvae instinctively seek refuge from predators and strong currents. The "helix recess" design was inspired by watching larvae in nature, which almost always choose tight, sheltered spots to begin their transformation.

But geometry alone isn't enough.

Ordinary Portland cement seems like an obvious choice for underwater construction. It's cheap, durable, and widely available. There's just one problem: it kills coral larvae.

Well, not directly. But its surface pH in marine environments climbs to around 13 in pore solutions, creating a hostile microchemical environment. When Dutch researchers tested various concrete formulations, they found that CEM I (standard Portland cement) supported settlement rates of just 4% ± 3%, even with a four-week-old biofilm present.

Compare that to CEM III, a blend that incorporates ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBFS). Same test, same biofilm age: 30% ± 6% settlement. That's nearly eight times higher.

The difference? Magnesium content. GGBFS concrete releases more magnesium into the water column, and cold-water coral larvae are strongly attracted to it. The material also happens to have a lower carbon footprint than standard cement and better long-term durability in seawater. A rare conservation win where environmental and engineering interests align.

Terracotta clay tells a different story. Archireef in Hong Kong pioneered reef tiles from this material, marketing it as "non-toxic and fully eco-friendly." Early colonization data looks promising, and the material is genuinely inert in seawater. But porosity matters too. Geopolymers and lime-sediment substrates showed low settlement rates, possibly because they leach trace elements that interfere with biofilm development.

Material choice isn't just about durability. It's about creating chemical conditions that microbes like, so biofilms form, which then release the molecular signals that coral larvae recognize as "home."

"Three-dimensional printing with natural material facilitates the production of highly complex and diverse units that is not possible with the usual means of mold production."

- Prof. Ezri Tarazi, Technion's Architecture and Town Planning Faculty

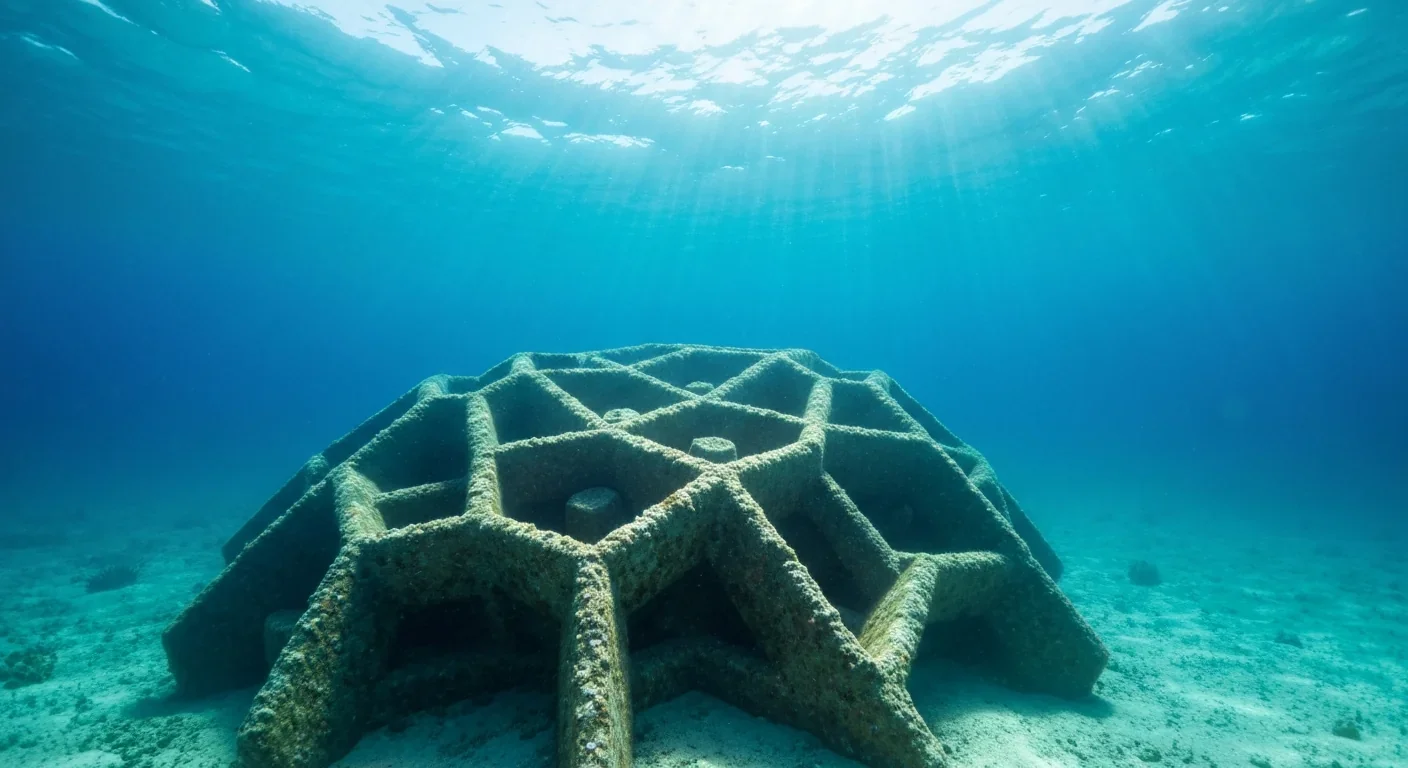

Here's where it gets interesting. The presence of a four-week-old biofilm increased larval settlement ninefold on CEM III substrates, jumping from 6% to 30%. For CEM I, even biofilm couldn't compensate for the underlying chemistry, maxing out at 4%.

Biofilm presence appears to override surface pH as a settlement cue. That's a critical design insight: engineers shouldn't just optimize substrate chemistry for larvae directly, but for the bacterial communities that colonize first and send out the chemical "all clear" signal.

This introduces a temporal dimension to reef design. A freshly deployed structure isn't functional until biofilms establish. That takes weeks to months depending on water temperature, nutrient levels, and microbial seed populations. Researchers at Bar-Ilan University are exploring ways to accelerate this by pre-seeding structures with microbial cultures before deployment, essentially jump-starting the ecological clock.

But there's another layer of complexity. Not all rough surfaces are created equal.

Surface roughness is good for larvae, right? More texture means more surface area, better grip, more hiding spots.

Mostly true. But when researchers at the Australian Institute of Marine Science tested composite substrates, they discovered something counterintuitive: mechanical heterogeneity at the sub-10 µm scale strongly deterred settlement.

Adding tiny glass fibers to create micro-roughness? Larvae avoided it. The theory is that at this scale, the surface feels hostile to the larva's sensory cells, even though it looks textured and complex at the millimeter scale that engineers typically design for.

This matters because 3D printing nozzles create layer lines and surface artifacts that vary depending on nozzle size, print speed, and material viscosity. Smooth prints underperform compared to rough prints, but there's a sweet spot. Too rough at the wrong scale, and you're accidentally building a repellent.

Computational design tools are now modeling surface texture at multiple scales simultaneously, using algorithms to optimize roughness between 100 µm and 5 mm while avoiding micro-heterogeneity below 10 µm. It's not enough to CAD a complex shape anymore. You have to simulate how the printer will render it, then predict how biofilms will colonize it, then estimate how larvae will respond.

Let's talk about real projects, not lab experiments.

Reef Design Lab has deployed structures in the Maldives and Australia. Early monitoring shows fish using them as shelter and algae colonizing within months. Octopuses have been spotted in Spanish projects in Santander Bay. The structures are working as habitat, though comprehensive coral recruitment data over multi-year timescales is still limited.

Archireef's terracotta tiles are installed in multiple Hong Kong sites. Denmark's Kattegat project is ongoing. The Florida Oceanographic Center has two large concrete structures in their Gamefish Lagoon, designed to support injured sea turtle recovery.

Each project took different design approaches. Some emphasize internal cavities for fish. Others focus on maximizing surface area for coral. A few integrate PVC inserts at the top for manual coral fragment transplants, hedging bets by combining artificial substrate with traditional restoration.

Cost is all over the map. Printera's Florida reefs cost roughly $4,000 each and took under 2.5 hours to print. That sounds reasonable until you realize reef restoration operates at scales measured in square kilometers, and these are small modules. The printer also has a height limit of one meter for the Delta WASP model, though Crane WASP systems can go larger at exponentially higher cost.

Scaling remains the central challenge. You can print a beautiful, biologically optimized reef tile in a morning. Printing 10,000 of them, transporting them to remote islands, and deploying them in rough seas? That's a different engineering problem entirely.

A single reef module costs $4,000 and takes 2.5 hours to print. To restore even 1% of lost habitat globally would require millions of modules, highlighting the scalability challenge.

Modern 3D-printed reefs aren't hand-designed by marine biologists sketching on whiteboards. They're algorithmically generated by software that combines photogrammetry scans of healthy natural reefs, environmental DNA sampling to identify local species, and parametric design rules that encode biological principles.

Bar-Ilan University's team scans underwater photographs to create 3D models of reefs, then uses those as training data for algorithms that can generate variations optimized for different environments. Crucially, the system allows feedback: post-deployment monitoring data can be fed back into the design loop to iteratively improve future structures.

This is closer to machine learning than traditional engineering. The software learns what works by analyzing which structures get colonized fastest, then generates new designs predicted to perform better. It's still early days, but the principle is sound - leverage computation to explore design space faster than humans can by hand.

Biomimicry plays a big role here. Natural reefs have fractal geometry, with structural complexity at multiple scales from centimeters to meters. Algorithmic design can replicate this automatically, generating sinuous curves, overhangs, and internal cavities that would be tedious or impossible to model manually.

Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations let engineers predict water flow through structures before printing them. This affects nutrient delivery to settled corals and influences how larvae are transported to different surfaces. A poorly designed flow pattern can create dead zones where water stagnates, or high-velocity channels that scour biofilms away.

Some teams are experimenting with AI optimization, training neural networks on reef performance data to suggest novel geometries humans wouldn't think of. It's speculative, but the data requirements are manageable because settlement outcomes can be measured in months rather than years.

Artificial reefs aren't new. Coastal communities have been sinking old ships, concrete modules, and "reef balls" for decades. These structures create habitat and attract fish, but they're blunt instruments compared to natural reefs.

Traditional reef balls are cast in molds, which limits geometric complexity. You can't create internal cavities with twisting passages or overhang structures that shelter larvae from predators. 3D printing removes those constraints entirely, allowing engineers to build geometries that would require impossibly complex molds.

Sunken ships work well for fish habitat but offer little for coral larvae. The metal surfaces are chemically unfriendly and lack the micro-texture that biofilms prefer. Concrete blocks are better but still lack the multi-scale complexity of natural reef structures.

Quantitative comparisons are sparse because long-term monitoring is expensive and few studies directly pit 3D-printed structures against traditional ones in controlled deployments. Anecdotal evidence suggests printed structures get colonized faster, but "faster" doesn't necessarily mean "better" in the long run. Ecosystem development takes decades, and most 3D-printed reef projects are less than five years old.

The real advantage of 3D printing isn't just geometry. It's customization. Traditional methods give you a few standard designs. 3D printing lets you optimize for specific sites, tailoring substrate chemistry, surface texture, and structural configuration to local conditions. That flexibility could matter a lot if restoration moves toward personalized, data-driven approaches rather than one-size-fits-all solutions.

Here's the uncomfortable truth: despite all this innovation, 3D-printed reef restoration remains tiny compared to the scale of reef loss.

Printing is slow. Even with industrial printers running 24/7, you're producing modules measured in cubic meters per day. Reefs degrade at scales measured in square kilometers per year. The Great Barrier Reef alone covers 344,000 square kilometers. If you wanted to replace even 1% of lost habitat with 3D-printed structures, you'd need millions of modules.

Transport is brutal. Concrete structures are heavy. Shipping them to remote islands adds enormous cost and logistical complexity. You can't just print them on-site either, unless you're building a portable concrete 3D printer that works in tropical conditions with unreliable power.

Deployment is dangerous and skill-intensive. Divers must place structures precisely, often in strong currents or poor visibility. Large modules require cranes or specialized vessels. Monitoring requires repeat dive surveys to assess colonization.

Material costs add up quickly. GGBFS concrete is more expensive than standard cement. Ceramic printing is even pricier. Terracotta clay is cheap but less durable. Every material choice involves trade-offs between cost, performance, and durability.

Some researchers argue that hybrid approaches make more sense: use 3D-printed modules as seed structures, then accelerate colonization by transplanting coral fragments or actively seeding larvae during spawning events. Think of printed reefs as scaffolding rather than replacement habitat.

Not everyone is sold on 3D-printed reefs. Skeptics worry about greenwashing - corporations funding small, photogenic reef projects to offset far larger environmental damage elsewhere. A tech company deploying a few printed tiles while its data centers consume gigawatts sends a mixed message.

There's also concern about unintended consequences. What happens when these structures degrade over decades? Do they leach microplastics or concrete particulates that accumulate in sediments? Long-term ecological impacts are unknowable because the technology is too new.

Some marine biologists argue that focusing on artificial substrates distracts from the real problem: climate change. If warming and acidification continue unchecked, it won't matter how perfectly engineered your reef tiles are. Dead coral doesn't care about surface texture.

That critique is fair but incomplete. Yes, nothing fixes reefs without addressing carbon emissions. But restoration buys time. If we can keep remnant populations alive through the next few decades, they might survive long enough for atmospheric CO₂ to stabilize or for coral adaptation to catch up through assisted gene flow.

Printed reefs aren't a silver bullet. They're a tool in a much larger conservation toolkit that includes emissions reduction, marine protected areas, coral gardening, genetic rescue, and pollution control. Evaluated in that context, they're a reasonable bet - worth testing, refining, and deploying strategically in high-value sites.

"Offering 3D-printed habitats is a way to provide reef organisms a structural starter kit that can become part of the landscape as fish and coral build their homes around the artificial coral."

- Danielle Dixson, University of Delaware

The technology is advancing fast. Next-generation designs are exploring multi-material printing, where a single structure combines GGBFS concrete for structural strength with ceramic tiles for optimal larval settlement. Researchers are testing controlled-release substrates that gradually release calcium and magnesium ions to stimulate coral growth after settlement.

Some teams are integrating printed shelters into existing infrastructure, attaching them to seawalls and artificial breakwaters to add ecological function to structures built for coastal defense. This dual-purpose approach makes economic sense because it leverages existing deployment budgets.

Field monitoring is getting more sophisticated too. Autonomous underwater vehicles equipped with cameras can survey reef colonization at regular intervals, feeding real-time data back to design teams. Machine learning models analyze thousands of images to identify coral recruits, measure growth rates, and detect early signs of stress.

The cost curve is trending down as printing technology matures and production scales up. Today's $4,000 module might cost $1,000 in five years and $500 in ten. At those price points, restoration becomes viable at much larger scales.

But the fundamental challenge remains: we're trying to rebuild in years what nature took millennia to create, and we're doing it while the ocean itself is changing faster than corals can adapt. It's hubris to think technology alone can solve this. But it's also fatalism to assume nothing we do matters.

In 2026, coral restoration is still more art than science, more hope than proven solution. Every 3D-printed module deployed into tropical waters is an experiment, a data point in a global effort to understand whether human engineering can ever replicate the intricate complexity of natural ecosystems.

The optimistic case is that within a decade, we'll have reliable, scalable methods for producing reef substrate that accelerates natural recovery by 10x or more. Imagine coastal communities worldwide printing custom reef modules, deploying them during optimal spawning windows, and watching coral populations rebound in previously degraded areas.

The pessimistic case is that this all becomes moot because atmospheric CO₂ crosses thresholds that make reef ecosystems untenable regardless of substrate quality. Or that the technology works locally but can't scale to meaningful impact before political will and funding evaporate.

The realistic case is probably somewhere in between: printed reefs will work in specific contexts, fail in others, and become one component of adaptive reef management strategies that combine multiple approaches tailored to local conditions.

What's certain is that marine engineers now have tools that didn't exist a decade ago. They can scan, model, print, deploy, and iterate faster than any previous generation of reef restoration practitioners. They can test dozens of designs in the time it used to take to test one.

That speed of experimentation gives us a fighting chance. Not certainty, but chance. And in the face of existential threats to ocean ecosystems, chance is worth pursuing with every tool we've got.

Whether baby corals ultimately accept our manufactured homes depends on whether we can solve thousands of small biological puzzles before the ocean changes too much to matter. So far, the larvae are teaching us that nature's engineering tolerances are tighter than we thought, and humility might be our most valuable design tool.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

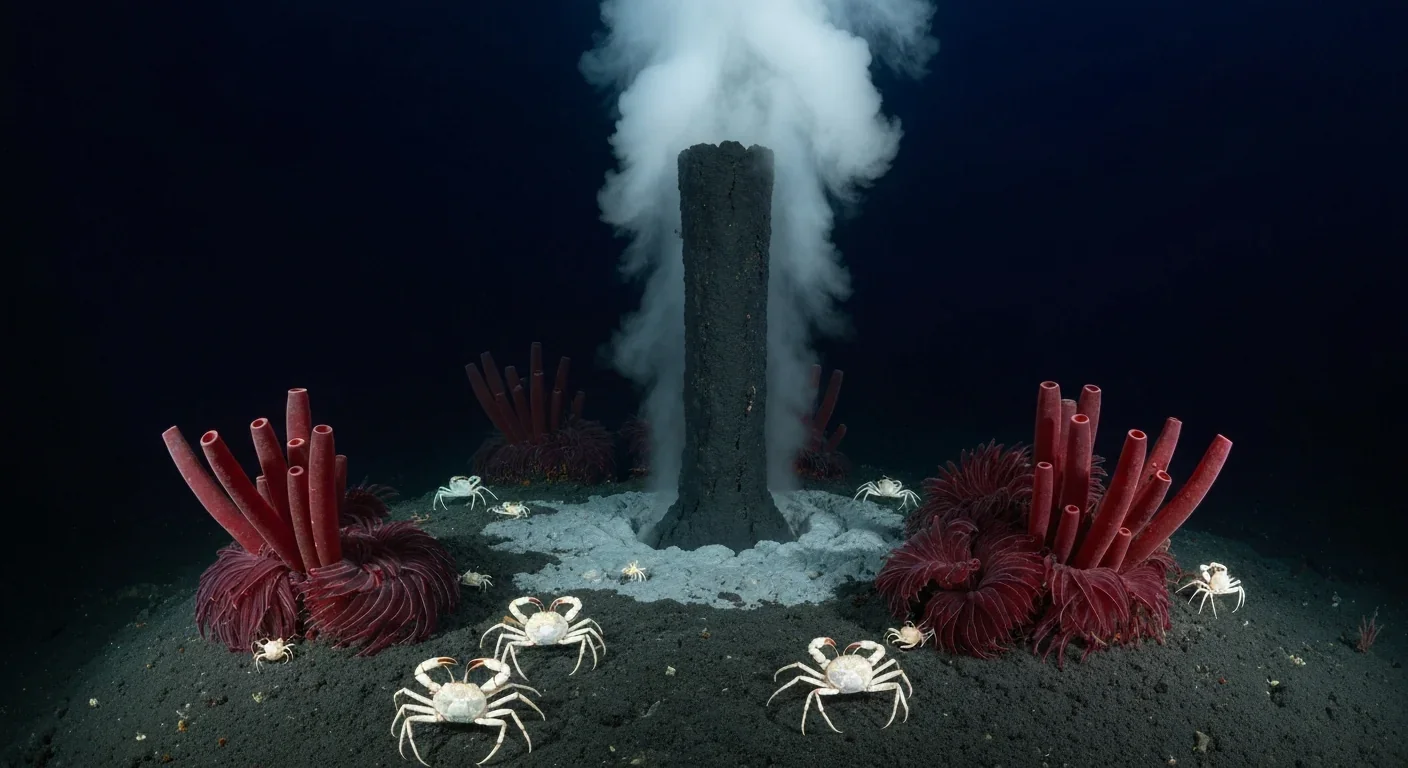

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.