3D-Printed Coral Reefs: Can We Engineer Marine Recovery?

TL;DR: The circular economy redesigns our production systems to eliminate waste entirely by keeping materials in continuous use. From Patagonia's repair programs to industrial symbiosis and digital watermarking technology, companies are proving that waste is a design flaw we can engineer away.

Every year, humanity produces over 2 billion tons of solid waste. If current trends continue, that number will balloon to 3.4 billion tons by 2050. We've built an economic system that takes, makes, and throws away at a scale the planet can't sustain. But what if waste wasn't an inevitable endpoint? What if our entire production model could be redesigned so trash simply doesn't exist?

This isn't wishful thinking. The circular economy is already transforming how we design, produce, and consume, turning yesterday's waste streams into tomorrow's valuable resources. From Patagonia telling customers not to buy their products to industrial parks where one factory's exhaust becomes another's raw material, companies worldwide are proving that waste is a design flaw, not a fact of life.

The circular economy rests on three core principles that fundamentally break from the linear take-make-dispose model. First, eliminate waste and pollution by designing them out from the start. Second, circulate products and materials at their highest value, keeping them in use as long as possible. Third, regenerate nature rather than just doing less harm.

These aren't incremental improvements. They represent a complete reimagining of how economies function. In a linear system, value flows in one direction: from extraction through production to disposal. In a circular system, value cycles continuously. Products become services. Waste becomes feedstock. The end of one process marks the beginning of another.

Design decisions made in early product development lock in 70-80% of a product's final cost and environmental impact. That's where circular thinking creates the biggest leverage. When designers start with questions like "How will this be disassembled?" or "What happens when this product's first life ends?", entirely new solutions emerge.

The Ellen MacArthur Foundation, which has united over 1,000 organizations worldwide behind circular goals, frames it simply: a circular economy eliminates waste and pollution, circulates products and materials at their highest value, and regenerates nature. It's designed to thrive within planetary boundaries, not exceed them.

Patagonia made headlines with their "Don't Buy This Jacket" campaign, but the outdoor apparel company wasn't just making a political statement. They were pioneering a business model where durability, repair, and reuse generate more value than constant consumption.

Patagonia's CEO recently reminded the industry why this approach works financially, not just ethically. By building products that last decades and offering lifetime repairs, Patagonia creates customer loyalty that transcends any single purchase. Their Worn Wear program takes back used gear, repairs it, and resells it, capturing value that would otherwise be lost to landfills.

This model is spreading. At least 15 outdoor gear brands now run repair, resell, or upcycle programs. What started as a niche sustainability initiative has become a competitive differentiator. Customers increasingly choose brands that help them consume less, not more.

The shift extends beyond outdoor gear. Product-as-a-service models are redefining ownership across industries. When Philips sells lighting as a service instead of light bulbs, they maintain ownership of the fixtures and have every incentive to make them last as long as possible. The customer gets light; Philips retains materials.

One of circular economy's biggest technical challenges has been sorting waste streams with enough precision to recover high-value materials. That's changing thanks to digital watermark technology pioneered by the HolyGrail initiative.

These tiny, imperceptible codes embedded in packaging create a digital product passport. When packaging reaches a sorting facility, scanners read the watermarks and separate materials at article level, distinguishing food-grade plastic from non-food-grade, different polymer types, and even brand ownership. This granularity wasn't possible with near-infrared sorting alone.

HolyGrail 2.0 proved the technology works in real commercial plants, not just labs. The initiative grew from 31 members to 176, demonstrating how industry-wide collaboration can accelerate technology adoption. By agreeing on a common standard upfront, competitors avoided the fragmentation that often stalls new systems.

The next phase, HolyGrail 2030, aims to prove economic viability across the entire value chain. Technical feasibility is necessary but not sufficient. For circular innovations to scale, they must deliver returns for every stakeholder, from brand owners to recyclers.

Industrial symbiosis takes circular thinking to the systems level. Instead of individual companies optimizing their own processes, entire industrial parks are designed so waste from one facility becomes raw material for another.

In Vietnam, industrial symbiosis represents a quiet revolution with billion-dollar potential. Steel mills supply slag to cement manufacturers. Chemical plants route waste heat to adjacent facilities. Wastewater from one process provides cooling or process water for another.

These symbiotic relationships don't happen by accident. They require physical proximity, compatible processes, and often regulatory frameworks that treat byproduct exchanges differently than waste disposal. But when the conditions align, the efficiency gains can be dramatic.

The economic logic is compelling. Companies participating in industrial symbiosis reduce disposal costs, secure cheaper inputs, and create revenue from materials they once paid to discard. The model has spread from pioneering sites in Denmark and Sweden to industrial zones across Asia, Europe, and North America.

Market forces alone won't drive circular transition fast enough. Policy is proving essential, particularly through Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) frameworks that make manufacturers responsible for products' entire lifecycle.

The EU Parliament recently approved EPR rules for textiles, requiring brands to financially support collection, sorting, and recycling infrastructure. Similar regulations are rolling out for packaging across multiple jurisdictions.

EPR fundamentally changes design incentives. When companies bear the cost of managing products at end-of-life, they suddenly have economic reasons to design for disassembly, use recyclable materials, and minimize packaging. What was once an externality becomes a line item.

Switzerland's circular economy approach combines EPR with broader resource efficiency standards, creating a comprehensive framework that addresses extraction, production, consumption, and recovery. The Swiss model shows how policy can coordinate action across the value chain.

Regulations also create level playing fields. When EPR requirements apply to all competitors, first movers aren't penalized for taking on additional costs. The EU's revised Waste Framework Directive extends this logic to food and textile waste, sectors that have historically escaped comprehensive regulation.

Standards and certification systems help companies navigate circular design and signal credibility to customers. The Cradle to Cradle Certified framework sets rigorous criteria across material health, material reutilization, renewable energy use, water stewardship, and social fairness.

Products earn certification levels (Bronze, Silver, Gold, Platinum) based on how well they meet circular principles. The framework pushes beyond "less bad" to "more good", asking not just "Does this product minimize harm?" but "Does it contribute positively to ecological and social systems?"

ISO 59010 provides another pathway, offering a practical playbook for companies transitioning from linear to circular business models. The standard helps organizations assess current practices, identify circular opportunities, and implement changes systematically.

These frameworks matter because circular economy can't remain a vague aspiration. Companies need clear metrics, verifiable standards, and third-party validation to move from principles to practice.

Biomimicry offers a powerful lens for circular innovation: studying nature's 3.8 billion years of R&D to solve human design challenges. Ecosystems produce no waste. Every output from one organism becomes input for another. Energy flows from the sun. Materials cycle indefinitely.

The Biomimicry Institute recently unveiled AskNature Chat, an AI-powered tool that helps designers find nature-inspired solutions to technical problems. Need a non-toxic adhesive? Look at how mussels attach to rocks. Want self-healing materials? Study how skin repairs itself.

Research on bioinspired approaches highlights both the potential and philosophical-ethical implications. Biomimicry isn't just about copying natural forms but understanding underlying principles, adaptation strategies, and ecosystem dynamics.

Why biomimicry matters for sustainability comes down to this: nature has already solved most of the problems we're trying to address, without toxic materials, waste, or fossil fuels. Learning from living systems accelerates circular innovation while reducing trial-and-error costs.

Textiles represent one of circular economy's toughest challenges. The industry produces massive volumes, uses complex material blends, and operates on fast-fashion cycles that prioritize cheap over durable. But change is coming.

Closed-loop textile recycling systems are revolutionizing sustainable fashion by breaking garments down to fiber level and spinning new yarn without virgin materials. The technical hurdles are significant since most clothing mixes cotton, polyester, elastane, and other fibers that are difficult to separate.

Chemical recycling offers one pathway, dissolving fabrics to recover pure polymers. Mechanical recycling tears materials apart and re-spins them, though this typically reduces fiber quality. Comprehensive guides to closed-loop systems detail the infrastructure, technology, and supply chain coordination required.

The Netherlands is working to close the textile loop through combined efforts in collection, sorting technology, and recycling capacity. Success requires coordination across brands, consumers, municipalities, and recyclers, each playing a role in keeping materials circulating.

Weaving sustainability into textile manufacturing means rethinking everything from fiber sourcing to dye chemistry to garment construction. The industry is beginning to design for disassembly, using mono-materials where possible and avoiding treatments that prevent recycling.

Electronic waste contains valuable materials - gold, silver, rare earth elements - often at higher concentrations than virgin ore. That makes e-waste less a disposal problem than a resource opportunity.

Recycling and urban mining in electronics turns discarded devices into feedstock. One ton of circuit boards contains more gold than one ton of gold ore. The challenge is extraction: electronics pack dozens of materials into compact assemblies using adhesives and proprietary designs that resist disassembly.

Why recycling your phone costs more than you think reveals the economic reality. Manual disassembly is labor-intensive. Automated systems require substantial investment. Recovered materials compete with cheap virgin extraction. Without policy intervention or design changes, phone recycling often loses money.

This is where design for circularity becomes critical. If manufacturers built phones for easy disassembly, standardized components, and transparent material composition, recovery economics would improve dramatically. Some jurisdictions are moving toward "right to repair" and design-for-recycling mandates to force this shift.

Circular economy transformation isn't just for corporations and policymakers. Individual choices and organizational practices matter.

Start by extending product life. Repair instead of replace. Buy durable goods designed to last. Use products fully before upgrading. These behaviors signal market demand for longevity, influencing how companies design and price offerings.

Choose circular business models when available. Rent, lease, or subscribe instead of owning. Buy refurbished. Participate in take-back programs. Support brands that prioritize repair, reuse, and material recovery.

For organizations, integrating circular design into product development requires upfront investment but pays dividends through reduced material costs, enhanced brand value, and future-proofed operations.

Advocate for supportive policy. EPR, right-to-repair, design standards, and infrastructure investment create conditions where circular practices can scale. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation identified misaligned market incentives, missing infrastructure, and lack of investment as primary barriers. Policy can address all three.

Measure and track circular performance. What gets measured gets managed. Companies increasingly report on material circularity, product longevity metrics, and waste diversion rates. Tools like product lifecycle management systems integrate circularity into design, engineering, and supply chain decisions from day one.

Circular economy isn't charity. The business case for circular models centers on capturing value that linear systems leave on the table. When products are designed for multiple use cycles, companies can sell the same materials many times over.

Service models generate recurring revenue streams. Instead of one-time sales, businesses build ongoing customer relationships. Maintenance, upgrades, and eventual material recovery create additional touchpoints and revenue opportunities.

Material security matters too. Building circular supply chains reduces dependence on virgin extraction subject to price volatility, geopolitical risk, and environmental constraints. Companies with circular supply chains insulate themselves from these uncertainties.

Climate benefits translate to economic value as carbon pricing expands. Circular practices typically reduce emissions through material efficiency, eliminating waste processing, and displacing virgin production. As governments implement carbon taxes and cap-and-trade systems, these reductions gain monetary value.

Emerging technologies are accelerating circular transitions. Digital product passports create transparency across supply chains, tracking materials from production through multiple use cycles to final recovery. Blockchain and IoT sensors enable this traceability at scale.

Advanced sorting technologies continue improving. AI-powered systems identify materials faster and more accurately than manual sorting or single-sensor approaches. This improves economics by increasing recovery rates and material purity.

Chemical innovations unlock new recycling pathways. Enzymes that break down plastics, solvents that separate blended fibers, and processes that recover rare earth elements from electronics expand what's technically recyclable.

Soil carbon credits represent a parallel circular system for agriculture, capturing atmospheric carbon in soils and creating financial incentives for regenerative practices. The market faces challenges around measurement and verification but shows how circular principles extend beyond manufactured goods.

The Three Horizons innovation model helps organizations navigate circular transition by balancing current operations, emerging practices, and transformational innovations simultaneously. Companies can optimize existing processes while piloting new models and investing in longer-term capabilities.

Linear economics worked when the world seemed infinite and waste invisible. Neither assumption holds anymore. We face material constraints, climate destabilization, and pollution crises that demand fundamental redesign.

The circular economy offers more than waste management. It's a framework for prosperity within planetary boundaries, where economic activity regenerates rather than degrades natural systems.

What it really takes to design for circularity is commitment across entire value chains. Designers must think beyond form and function to material flows. Manufacturers need reverse logistics as sophisticated as forward supply chains. Policymakers must align incentives with circular outcomes. Consumers have to value durability and repairability.

The transformation is already underway. HolyGrail is sorting packaging with unprecedented precision. Patagonia is proving that "buy less" can be profitable. Industrial parks are achieving symbiosis. Textiles are closing loops. Electronics are becoming urban mines.

None of this is easy. Circular transitions face entrenched infrastructure, incumbent business models, and the sheer inertia of systems built over centuries. But the alternative - continuing to treat a finite planet as an infinite dump - isn't viable.

The circular economy transforms waste from an inevitable endpoint to a design flaw we're learning to eliminate. Every product designed for longevity, every business model based on service, every policy requiring producer responsibility, and every consumer choosing durability over disposability moves us closer to systems where trash simply doesn't exist.

That's not utopian fantasy. It's engineering, economics, and increasing necessity converging toward the same conclusion: the most valuable resource we have is the one we've already extracted. Keeping it in play isn't just environmental stewardship. It's the next chapter in economic evolution.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

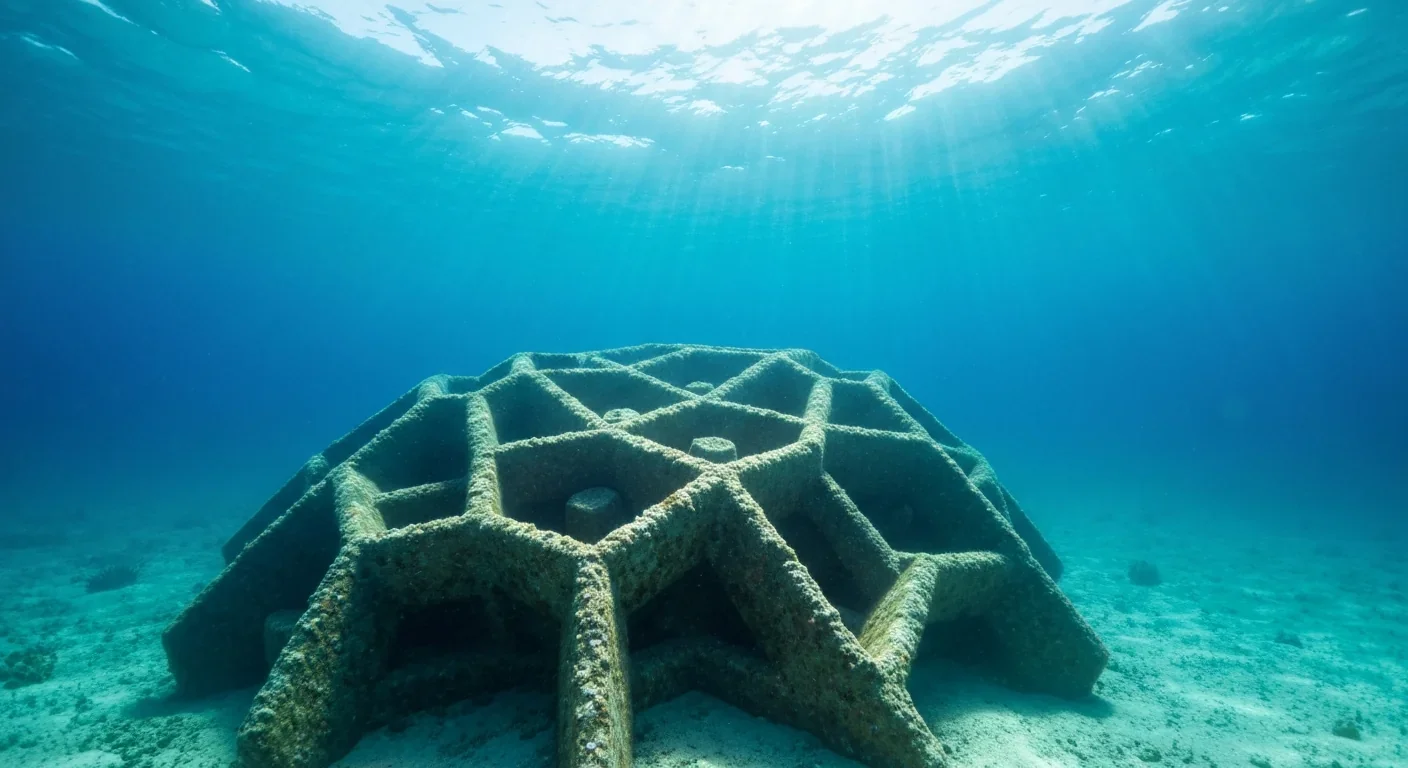

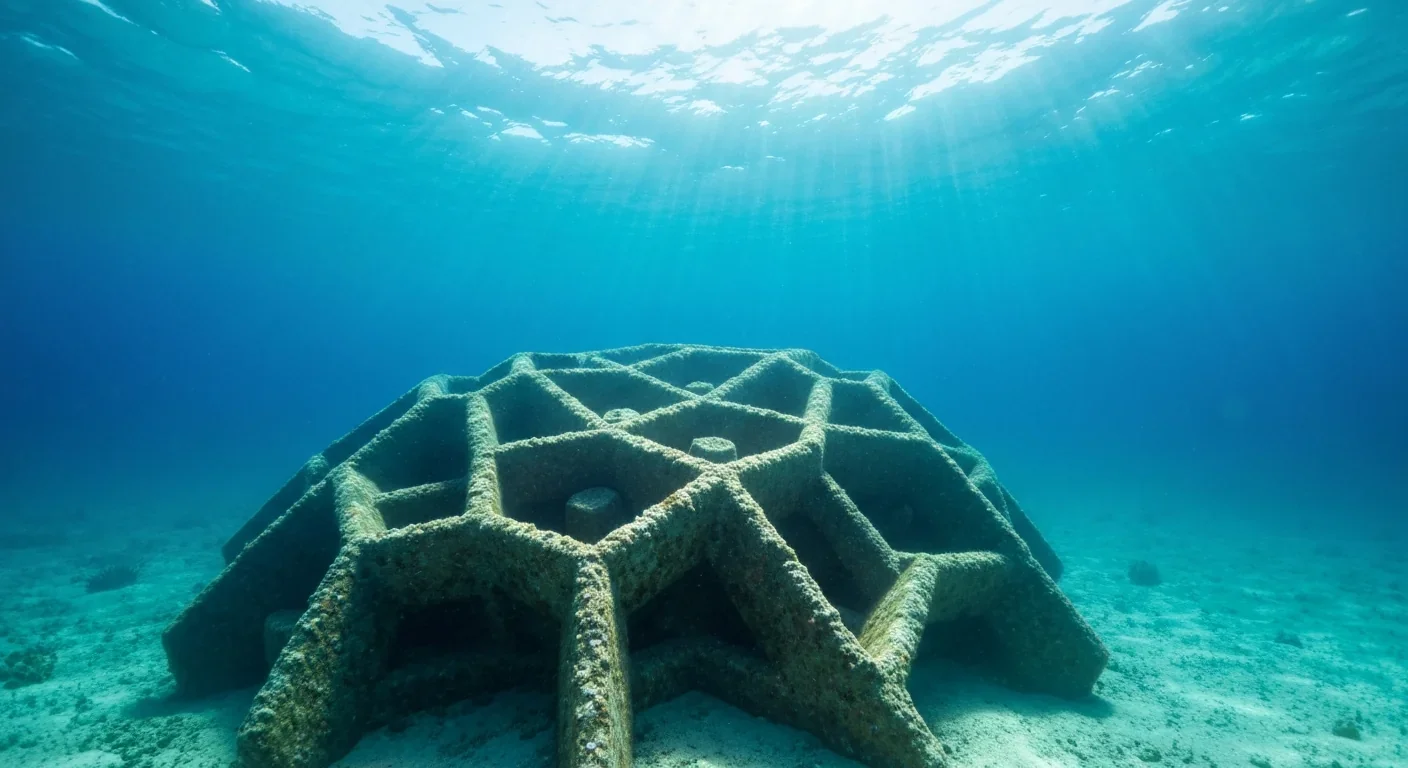

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

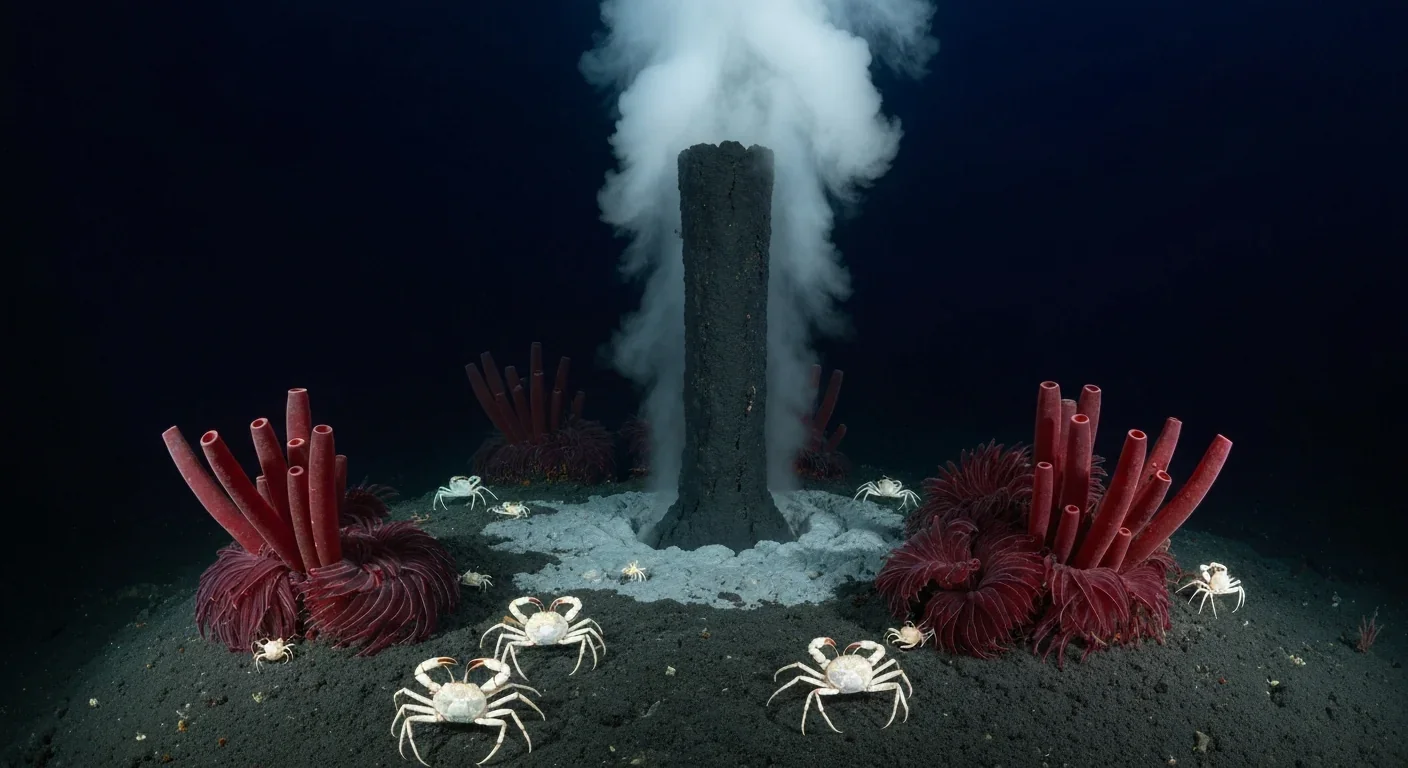

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

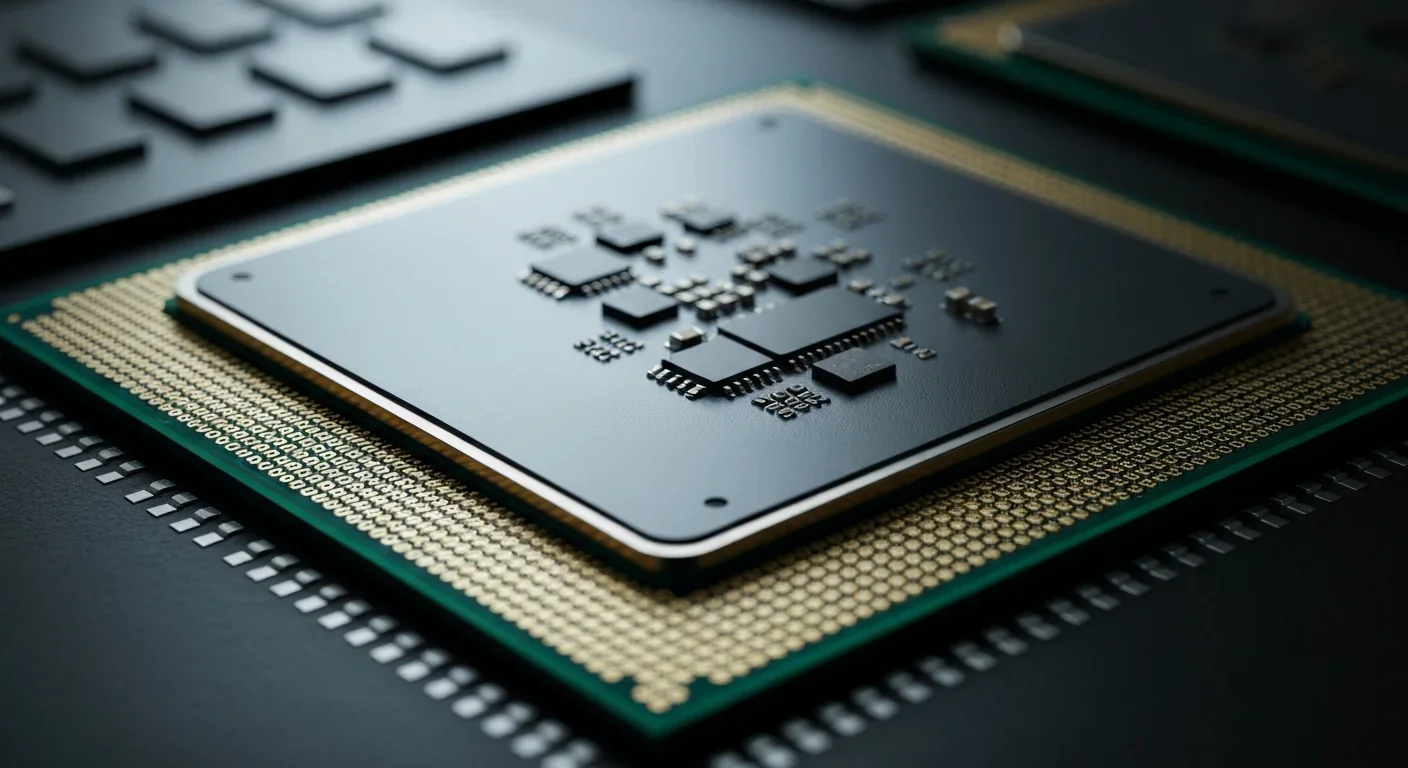

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.