3D-Printed Coral Reefs: Can We Engineer Marine Recovery?

TL;DR: Architects are designing skyscrapers as 'material banks' that can be systematically deconstructed and their components reused, turning cities into sustainable resource hubs. Material passports digitally track every component's value, while modular construction and reversible design principles can reduce demolition waste by up to 90%.

By 2050, experts predict that urban areas will contain more valuable materials than many natural mining sites. The construction sector already gobbles up 50 percent of Europe's raw materials and generates 60 percent of its waste. But architects worldwide are flipping this equation upside down, designing skyscrapers not as monuments of permanence but as carefully organized material warehouses, ready to be harvested when their time is done.

These aren't just greener buildings. They represent a fundamental reimagining of architecture itself, where every beam, panel, and fixture carries a digital passport documenting its journey and future value. Welcome to the era of urban mining skyscrapers, where cities become self-sustaining resource hubs and demolition transforms into strategic material recovery.

At the heart of this transformation sits a deceptively simple innovation: the material passport. Think of it as a birth certificate, medical record, and instruction manual rolled into one digital document for every component in a building. Madaster, a pioneering platform in this space, records materials and products incorporated into buildings, tracking quality, origin, and crucially, disassemblability.

These aren't static files gathering digital dust. They're living inventories that transform how stakeholders think about building value. When Triodos Bank designed its new office in Zeist, Netherlands, every component was catalogued in an online repository, effectively creating a material bank that could be resold in the future. The building achieved a BREEAM Outstanding Certificate while fundamentally challenging the notion that structures must be permanent.

Material passports give materials an identity that outlives any single building, ensuring components receive and keep value through possible reuse after deconstruction.

Material passports do something remarkable: they give materials an identity that outlives any single building. According to research on material passports, this identity ensures materials receive and keep value through possible reuse after deconstruction. Dutch studies suggest this approach can increase a building's residual value by 7-15%, turning what would be demolition waste into depreciable assets.

The economic logic is compelling. Buildings become living balance sheets where every component has tracked value. Investors can assess not just what a structure is worth today, but what its constituent materials will be worth in 30, 50, or 100 years. This shifts incentives dramatically. Suddenly, using demountable components and enabling higher collateral valuations makes financial sense, not just environmental sense.

Creating a material bank requires rethinking construction from the ground up. Traditional buildings use permanent connections - welds, chemical adhesives, embedded fasteners - that make selective deconstruction nearly impossible. Reversible building design takes the opposite approach: structures are deliberately engineered to come apart.

The principles sound straightforward but demand meticulous planning. Architects favor mechanical fasteners over chemical bonds, modular components over custom builds, and accessible joints over hidden connections. Zero-bonding systems, inspired by Japanese wood-joining technique kigumi, dispense entirely with permanent bonding, relying instead on precise fit and inherent structural strength.

This isn't just theory. The People's Pavilion in Eindhoven was built entirely from borrowed or recycled construction materials and returned to owners after use. "We took the circular idea to a maximum level," explained Peter van Assche of Bureau SLA. Every element was tracked, and every connection was reversible.

Structural engineering in these buildings becomes a fascinating constraint puzzle. How do you create robust, safe high-rises that can also be taken apart? EVstudio's Reversible Design system demonstrates one answer: prefabricated modular components designed from conception for easy disassembly. The approach offers the same benefits as traditional modular construction - faster build times, consistent quality, cost savings - while adding adaptability and future-proofing.

"We took the circular idea to a maximum level."

- Peter van Assche, Bureau SLA

The integration between architecture and engineering must be seamless from day one. Poor coordination between disciplines can create systems that look reversible on paper but prove difficult to disassemble in practice. Reversible Architecture and Reversible Engineering, as EVstudio terms them, must work in perfect harmony to avoid locking in components that can't be extracted without damage.

Modularity amplifies the urban mining concept. When building components are standardized and interchangeable, they become more valuable as future resources. Modular off-site construction now leverages AI-augmented BIM to create complex geometries - staggered modules, curved surfaces, angled walls - while keeping each unit standardized for assembly and later disassembly.

EVstudio's Reversible Design can reduce demolition waste by up to 90% compared to traditional methods. That's not incremental improvement; it's a categorical shift in how we think about building lifecycles. Prefabricating components offsite cuts construction timelines and labor costs while reducing material waste before structures even stand.

Reversible Design can reduce demolition waste by up to 90% compared to traditional construction methods - a categorical shift in how we approach building lifecycles.

But modularity delivers another advantage rarely discussed: it creates secondary markets for building components. Because components are designed as personal property rather than fixed real estate, developers can buy, sell, or trade modules. This flexibility opens entirely new exit strategies and business models.

The Universeine project in Saint-Denis, France - an Olympic athlete village - illustrates this approach at scale. Built primarily of timber with minimal concrete, the complex was explicitly designed for later deconstruction and conversion to mixed-use development. It's not just a temporary structure; it's an investment in future materials with a current use case.

Digital tools make this possible. BIM integration allows project teams to embed material data directly into digital building models, automating updates as materials are added, modified, or removed. These models become the operational foundation for material passports, tracking component locations, specifications, and recovery procedures.

Financial incentives drive adoption faster than environmental concern, and material banks offer compelling economic advantages. Tax benefits alone make the approach attractive: major portions of reversible buildings can be treated as personal property, enabling cost segregation and accelerated depreciation.

Think about traditional demolition economics. Structures are torn down, materials are mixed into waste streams, and disposal costs money. The building owner pays to destroy value. With material banking, that equation inverts. Components retain documented value, creating assets on balance sheets rather than liabilities in landfills.

Insurance and financing industries are taking notice. Buildings with comprehensive material passports and proven deconstruction plans present different risk profiles than conventional structures. They're less likely to become stranded assets if market conditions shift because they can be reconfigured or relocated rather than abandoned.

Madaster's material passports meet requirements for various certifications and subsidies, helping projects achieve sustainability objectives while accessing financial incentives. Regulatory compliance becomes easier when every material and component is documented and tracked throughout its lifecycle.

The secondary market potential is just emerging. Right now, reselling building components happens through informal channels with high transaction costs. As material passports standardize documentation and digital marketplaces develop, trading structural elements could become as routine as trading construction equipment.

Early movers are already seeing financial benefits. Projects with detailed material documentation report faster permitting, easier financing, and premium valuations. Investors increasingly recognize that buildings designed for circularity are less exposed to future regulatory risk as governments tighten construction waste mandates.

Europe leads in practical implementation, driven partly by regulatory pressure and partly by cultural emphasis on resource efficiency. The BAMB 2020 project - Buildings as Material Banks - brought together 16 European parties including universities, building companies, and policy makers to develop reversible construction standards.

The INBUILT Project advanced urban mining concepts across multiple EU member states, demonstrating that material passports and reversible construction could work at scale. These weren't just pilot programs; they created frameworks that subsequent projects could adopt and refine.

Real buildings, not just concepts, now embody these principles. Beyond Triodos Bank and the People's Pavilion, projects across the Netherlands, Belgium, and France demonstrate various approaches to material banking. Some emphasize modular systems, others focus on sophisticated digital twins, and still others experiment with novel connection systems.

What's striking is how diverse the solutions are. There's no single template for creating a material bank building. Architects adapt principles to local contexts, building types, and material availabilities. A residential tower in Amsterdam employs different strategies than an office complex in Brussels or a mixed-use development in Lyon.

Yet common patterns emerge. Successful projects integrate material passports early in design, coordinate architecture and engineering from conception, select materials for recovery potential, and establish clear documentation protocols. They also engage with future users and deconstruction specialists during planning, not as an afterthought.

The Crystal Palace, designed by Joseph Paxton in 1851, offers historical precedent. This temporary structure used prefabricated modular iron and glass systems enabling rapid assembly, relocation, and eventual disassembly. What drove reversible design then was economic necessity; today it's environmental imperative combined with economic opportunity.

Don't mistake this vision for simple execution. Material bank buildings face genuine technical hurdles. Connections must be strong enough for decades of use yet accessible for future disassembly. That's a design paradox requiring innovative solutions.

Fire safety codes, structural regulations, and weatherproofing standards weren't written with reversible buildings in mind. Gaining approval often requires extensive documentation and testing to prove that demountable systems meet performance requirements. Regulators trained on permanent construction naturally question whether reversible designs sacrifice safety for sustainability.

Material passport maintenance presents another challenge. Buildings exist for decades, changing hands multiple times. How do you ensure digital documentation stays current through renovations, ownership transfers, and management changes? The concept of material passports requires that passports be kept up to date and maintained throughout a building's life, but mechanisms for guaranteeing compliance remain underdeveloped.

Without legislative support, material passports' potential remains limited because building codes rarely recognize materials as depreciable assets throughout their multi-building lifecycle.

Standardization emerges as a persistent barrier. Without industry-wide standards for material documentation, connection systems, and component dimensions, each project effectively starts from scratch. The lack of standardisation and regulation creates inconsistencies and difficulties for implementation, limiting the secondary market potential that makes material banking economically attractive.

Digital infrastructure lags behind ambition. While platforms like Madaster provide material passport services, integration with broader building management systems, regulatory databases, and secondary markets remains fragmented. AI-assisted updates and automation within BIM show promise, but most implementations still require substantial manual data entry and maintenance.

Material science itself presents frontiers. Many high-performance materials crucial for modern construction - specialized composites, advanced concrete mixes, high-grade steel alloys - aren't designed for disassembly or recycling. Developing materials that maintain performance while enabling recovery requires research investment and market development.

Yet innovations keep emerging. Digital twins now incorporate material passport data, creating dynamic models that track building performance and material conditions in real-time. IoT sensors monitor structural loads, environmental exposure, and component wear, feeding data back to passports and informing recovery decisions.

Some architects are experimenting with corrugated cardboard, scaffolding, metal profiles, and slender wooden ribs - unconventional materials that challenge assumptions about permanence and durability. These explorations ask fundamental questions about how long buildings need to last and what trade-offs we're willing to make for reversibility.

Market dynamics alone won't drive transformation at the necessary scale. Without legislative support, material passports' potential remains limited because building codes rarely recognize materials as depreciable assets.

European regions are moving fastest on policy frameworks. The EU's Circular Economy Action Plan explicitly addresses construction materials, setting targets for resource recovery and mandating transparency in material sourcing. Some member states go further, requiring material passports for large construction projects or offering tax incentives for designs that facilitate deconstruction.

France's environmental regulations now encourage reversible construction in public buildings. The Netherlands incentivizes material passport adoption through subsidy programs. Belgium experiments with deposit-refund schemes for building components. These aren't uniform policies, but they signal regulatory direction.

Yet challenges persist. Building codes are notoriously slow to evolve, reflecting decades of accumulated precedent and conservative risk assessment. Introducing reversible design principles requires not just new regulations but retraining code officials, revising engineering standards, and updating professional certifications.

Liability frameworks remain murky. Who's responsible if a component fails after being reused from another building? How do warranties transfer when materials move between structures? Insurance markets haven't developed products tailored to reversible construction's unique risk profile.

Intellectual property questions also emerge. If a building component is patented, can it be resold freely in secondary markets? Do material passports need to disclose proprietary manufacturing details that companies consider trade secrets? These legal puzzles lack clear answers.

Despite obstacles, policy momentum builds. As more demonstration projects prove technical viability and economic benefits, regulatory barriers that seemed insurmountable become negotiable. Early adopters are creating the evidence base that policy makers need to justify reform.

The environmental case for urban mining skyscrapers is straightforward but profound. Construction accounts for some 50 percent of raw material consumption in Europe and 60 percent of waste, according to United Nations estimates. Shifting even a fraction of that to material recovery would dramatically reduce environmental impact.

Carbon footprints tell the story. Producing virgin steel, concrete, and aluminum requires enormous energy, predominantly from fossil fuels. Recovering materials from existing buildings cuts embodied carbon significantly. A steel beam extracted from a deconstructed building and reused carries only the disassembly and transportation carbon, not the full production footprint.

"Material passports transform buildings from disposable commodities into durable goods with multiple lives."

- Building as Material Banks Initiative

The reduction compounds over building lifecycles. If materials cycle through three or four buildings over a century instead of being produced once and discarded, the cumulative environmental savings multiply. This long-term perspective shifts how we calculate sustainability, focusing on material flows over time rather than single-project impacts.

Designing for future reuse minimizes materials in landfills and reduces the environmental impact of deconstruction itself. Selective disassembly generates far less dust, noise, and waste than demolition by wrecking ball or explosive. Communities around building sites experience less disruption.

Water usage drops too. Material processing consumes vast quantities of water; material recovery requires far less. Mining operations, whether for metals or aggregates, often contaminate local water supplies; urban mining eliminates that pressure.

Biodiversity benefits emerge indirectly. Less demand for virgin materials means less habitat destruction from mining, quarrying, and logging. Natural landscapes remain intact when cities supply their own material needs through recovery and reuse.

Yet we should temper enthusiasm with realism. Not every component will be reusable. Some materials degrade, others become contaminated, and still others fall out of regulatory compliance. Real-world recovery rates will be lower than theoretical maximums. Even optimistic projections suggest 70-80% material recovery, not 100%.

Transport emissions matter too. Moving components between buildings consumes energy. If deconstruction happens in Paris and reuse occurs in Madrid, transportation carbon could offset some recovery benefits. Successful urban mining will need to emphasize local material loops where possible.

The net calculation still favors material banking overwhelmingly. But honest accounting requires including all impacts, not just the favorable ones.

While Europe pioneers policy and practice, different regions are developing distinct approaches to material banking shaped by local conditions and cultural values.

Japan's traditional architecture offers ancient wisdom. Japanese wood-joining technique kigumi has created structures that stand for centuries while remaining fully demountable. Temples are periodically disassembled, components are repaired or replaced, and buildings are reassembled - material banking before the term existed.

Singapore, facing extreme land constraints, treats building materials as strategic resources. The city-state explores underground material storage facilities where recovered components await reuse. Material passports integrate with national digital identity systems, creating comprehensive tracking.

North American adoption lags but shows promise. Cost pressures in construction create openness to modular approaches, even if environmental motivation is weaker. Developers increasingly recognize that adaptable buildings retain value better in changing markets.

In rapidly developing economies like India and Nigeria, material banking could leapfrog traditional construction methods. Why build permanent structures destined for demolition when you can create adaptable material banks from the start? The economic case is especially strong where infrastructure needs are immense and capital is scarce.

China presents a fascinating paradox. The country's construction boom created unprecedented material demand, but also generated expertise in large-scale prefabrication. If policy priorities shift toward circularity, China's manufacturing capacity could quickly pivot to producing standardized, recoverable building systems.

Cultural attitudes toward buildings vary dramatically. Some societies value permanence and tradition; others embrace change and adaptability. Material banking aligns more naturally with cultures that see buildings as tools rather than monuments. Marketing the concept requires tailoring messages to local values.

Geopolitical implications lurk beneath the surface. Countries with limited natural resources gain strategic advantage through effective urban mining. Material self-sufficiency reduces dependence on resource-exporting nations and insulates economies from commodity price volatility.

Realizing the urban mining vision requires workforce capabilities that barely exist today. Deconstruction specialists need to assess buildings, plan selective dismantling, and execute component recovery while maintaining quality. That's different from demolition crews or construction workers.

Architecture and engineering curricula must evolve. Tomorrow's designers need training in reversible principles, material passport systems, and lifecycle analysis. Many programs still emphasize permanent construction, leaving graduates unprepared for circular approaches.

Digital skills become essential. BIM literacy, data management, and passport platform proficiency matter as much as traditional drafting and specification writing. The integration of photorealistic PBR files and digital documentation bridges virtual and physical realms, requiring hybrid skill sets.

Code officials and inspectors need retraining too. Evaluating reversible buildings demands different expertise than assessing conventional construction. Understanding demountable connections, modular systems, and passport documentation becomes part of the regulatory role.

New career paths are emerging. Material passport specialists, deconstruction planners, component certification experts, and circular economy consultants barely existed a decade ago. Now they're in demand, and universities are developing programs to train them.

Labor unions and trade organizations are adapting. Some embrace the transition, seeing opportunities for skilled workers in assessment and selective disassembly. Others worry about job losses if construction slows because buildings last longer and materials cycle rather than being continually replaced.

The reality will likely be job transformation rather than elimination. Construction employment may shift from continuous new building to more maintenance, upgrading, and strategic reconfiguration. Workers need support through this transition - retraining programs, credential pathways, and income bridges.

What does this mean for you? If you're involved in real estate, construction, or investment, material banking will reshape your field within a decade. Projects without material passports may face financing challenges as lenders recognize long-term value in documented buildings.

For architects and engineers, mastering reversible design principles is becoming as essential as understanding structural loads or building codes. Clients increasingly ask about lifecycle costs and end-of-life plans, not just initial construction budgets.

Policy makers at every level should engage with material banking now. Zoning codes, building regulations, and economic development incentives all need updating to facilitate rather than hinder reversible construction. Cities that act early will attract innovation and investment.

Property owners of existing buildings might explore retrofitting material passports. Even structures not designed for disassembly benefit from comprehensive documentation. When renovation or end-of-life arrives, that information enables better material recovery than going in blind.

Students choosing career paths should know that circular construction skills will be in high demand. Whether your interest is design, engineering, policy, or business, material banking creates opportunities across disciplines. The field needs pioneers, not just followers.

For everyone else, the transformation will mostly happen invisibly. Buildings will look similar from outside, but their internal logic and ultimate destiny will be radically different. Cities will gradually become the mines we depend on, extracting value from past construction rather than distant landscapes.

The skyscrapers rising today might still be here in 2100, but the ones designed as material banks won't be locked into their current form. They'll adapt, reconfigure, and eventually provide raw materials for whatever architecture our descendants need. That's not just sustainability; it's humility about how much we can predict and wisdom about keeping options open.

The question isn't whether cities will become material mines - material scarcity and climate pressure make that inevitable. The question is whether we'll plan for it or stumble into it.

Every skyscraper designed today will eventually face deconstruction. We can treat that as a disposal problem requiring demolition and landfilling, or we can recognize it as an opportunity requiring preparation and documentation. Material passports transform buildings from disposable commodities into durable goods with multiple lives.

This architectural revolution connects to broader economic transformation. Circular economy principles are reshaping manufacturing, agriculture, and energy systems. Construction is simply catching up, applying lessons other sectors learned: waste is just poorly organized resources, and thoughtful design at the start avoids costly problems at the end.

We're still early in this transition. Most buildings go up the old way, designed for a single life and destined for demolition. But the trajectory is clear. Material passports' concept is being developed by multiple parties primarily in European countries, and adoption is accelerating. Within a generation, reversible design could be standard practice, not experimental innovation.

That future city looks different from today's. Cranes still rise and buildings still climb, but the logic underneath shifts. Architects think in terms of material flows over decades. Engineers design connections for both strength and accessibility. Developers value adaptability as much as location. And when structures finally come down, specialized crews harvest components for their next life, not their final resting place.

The most profound change is conceptual. Buildings stop being monuments - permanent statements about power and wealth - and become temporary arrangements of materials in useful configurations. That's not diminishment; it's realism. Nothing lasts forever, and pretending otherwise just makes the eventual transition more wasteful and traumatic.

Urban mining skyscrapers accept impermanence while planning for continuity. The specific building is temporary; the materials are durable. That perspective fits our moment better than permanent construction ever could. We're living through profound economic, environmental, and social transitions. Our buildings should be as adaptable as we need to be.

Welcome to the era where cities mine themselves, where demolition becomes harvest, and where looking up at a skyscraper means seeing not just impressive architecture but a carefully organized warehouse of tomorrow's resources. The future isn't built on virgin materials extracted from distant mines. It's built on what we already have, if we're smart enough to design for it.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

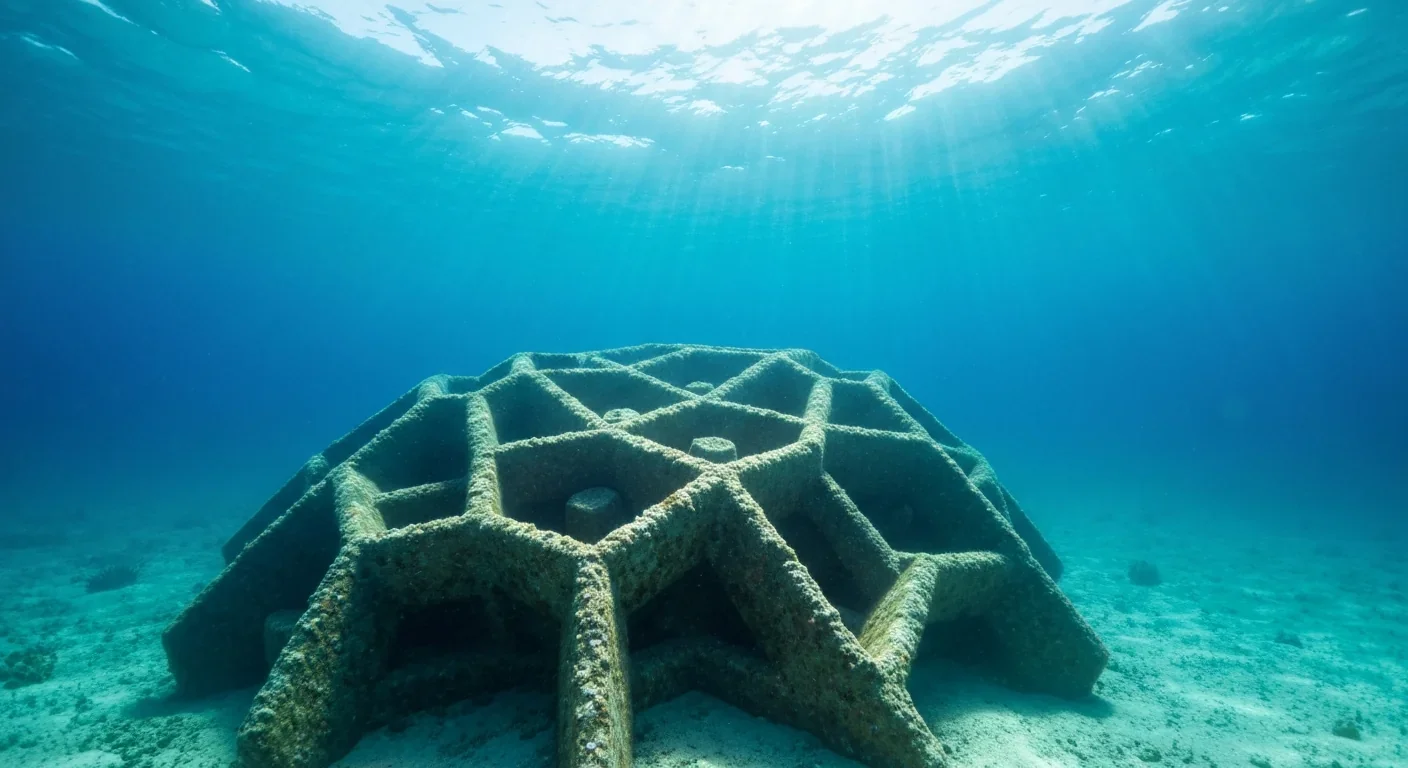

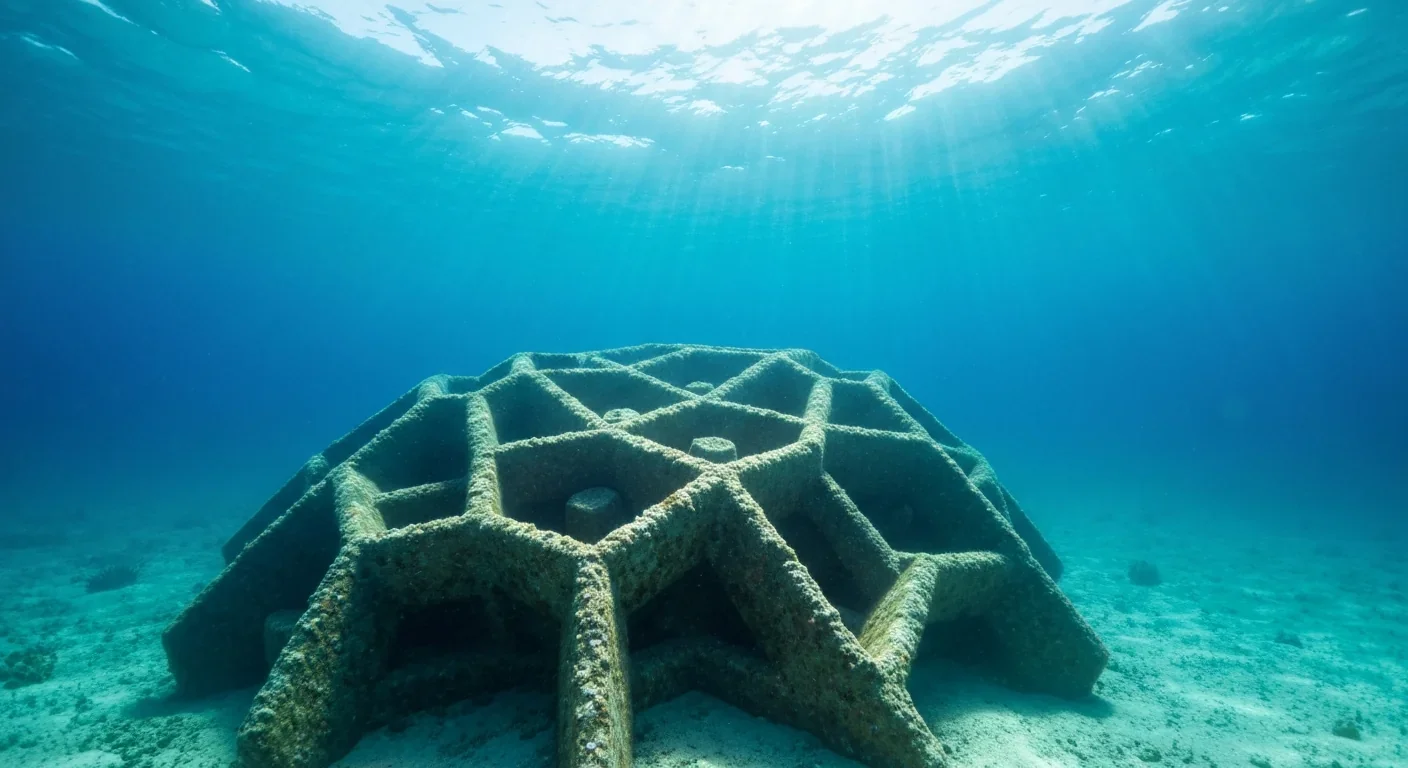

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

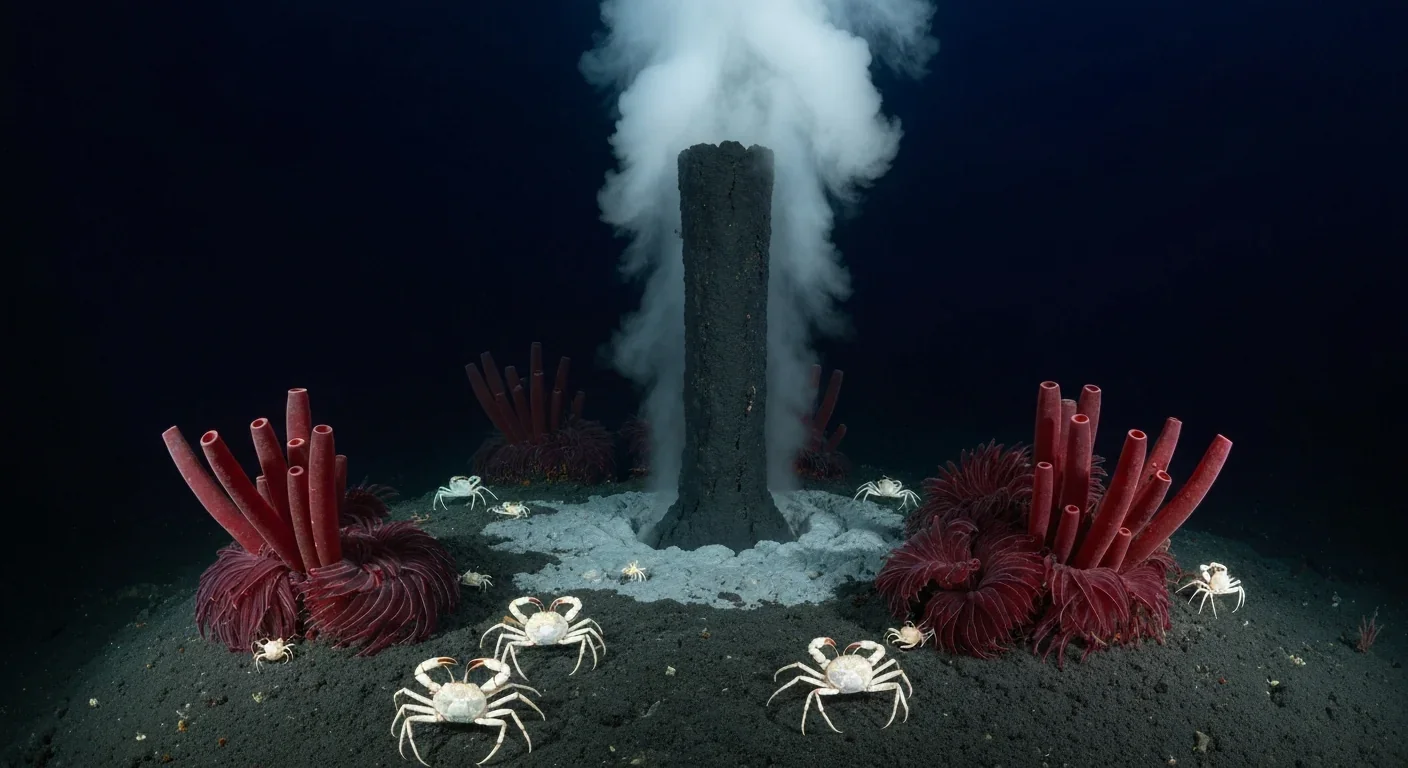

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

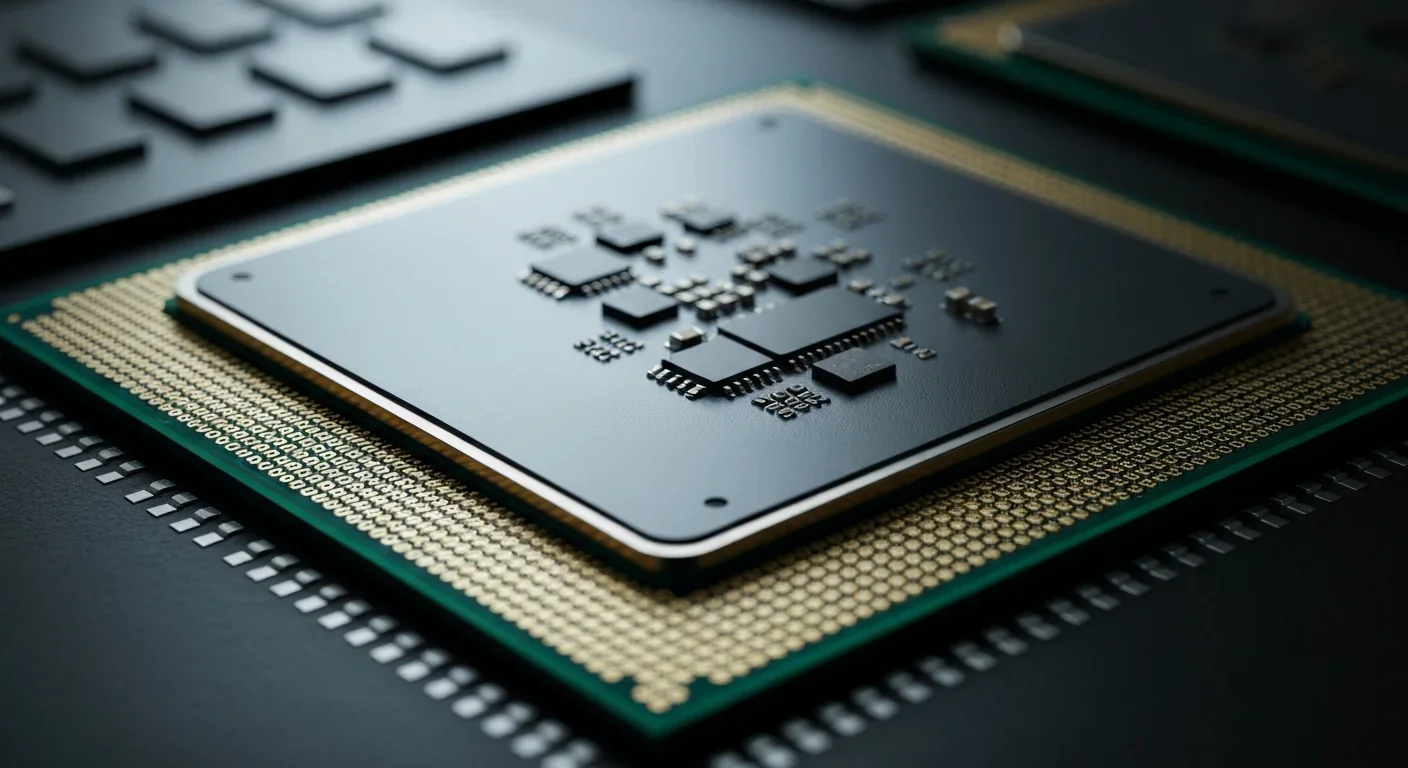

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.