3D-Printed Coral Reefs: Can We Engineer Marine Recovery?

TL;DR: Degrowth proposes intentional economic contraction in wealthy nations through progressive taxation, universal basic income, reduced working hours, and circular economies to achieve ecological balance. Real-world examples like Bhutan's Gross National Happiness, Scandinavia's circular initiatives, and global four-day workweek trials show these policies can maintain or improve wellbeing while cutting emissions. Critics warn of risks to developing nations, inflation, rebound effects, and political feasibility, but proponents argue a chosen recession beats ecological collapse.

By 2030, six of the nine planetary boundaries keeping Earth habitable will have been crossed. Yet even as climate disasters intensify, mainstream economists insist growth is non-negotiable. But a radical idea is gaining momentum among scientists and policymakers: what if we intentionally slowed the economy down?

This is the core philosophy of degrowth - a movement proposing we deliberately reduce production and consumption in wealthy nations to achieve ecological balance. It's not about poverty or scarcity, proponents argue, but about choosing prosperity without perpetual expansion. Think of it as a planned recession, but one designed to improve our lives rather than destroy them.

Degrowth challenges the fundamental assumption that has governed policy since the Industrial Revolution: that economic growth equals human progress. "Degrowth is important because it offers a critical rethinking of the traditional focus on economic growth, which often leads to environmental degradation and social inequality," explains the Institute of Sustainability Studies.

The numbers tell a sobering story. Nearly half of all historical carbon emissions occurred after 1990 - precisely when global climate action was supposed to begin. Transportation accounts for the largest share of direct U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, while 60% of electricity still comes from fossil fuels. The explosive growth of human production and social activities is the direct driver of climate change, making continuous GDP expansion incompatible with planetary survival.

Degrowth proponents argue this isn't a failure of technology or efficiency, but of the growth paradigm itself. The richest 1% consume twice as much CO₂ as the poorest 50%, revealing that overconsumption by elites - not population pressure - drives environmental collapse.

Unlike an economic crash, a planned contraction would be democratic and intentional. Here's how policy proposals break down:

Progressive Taxation to Fund Transition: Washington State's progressive tax package offers a real-world model. The proposal raises business taxes on corporations earning over $250 million annually and increases the base rate for wholesaling and manufacturing from 0.484% to 0.5%. It would generate nearly $12 billion over four years - funds that could finance universal basic income, job guarantees, and healthcare.

Closing the tax gap through enforcement creates additional fiscal space. Studies show a 6-to-1 return on IRS audits, and capital gains - highly concentrated among the top 1% - are taxed at lower rates than ordinary income despite discredited efficiency arguments justifying this preference.

Universal Basic Income to Decouple Survival from Growth: UBI trials in Namibia reduced household poverty from 76% to 37% and child malnutrition from 42% to 17% within one year. A 2024 U.S. study found that $1,000 monthly payments reduced work hours by just 1.3 hours per week - most spent on education or caregiving, not unemployment.

Georgetown professor Karl Widerquist calculated that guaranteeing UBI for all Americans above the poverty line would cost less than 3% of GDP - approximately $539 billion annually. By treating unpaid care work as economically valuable, UBI could substantially reduce gender-based economic disparities.

Reduced Working Hours Without Pay Cuts: The world's largest four-day workweek trial involved 2,896 employees across 141 organizations in six countries. Results were stunning: statistically significant improvements in burnout, job satisfaction, mental and physical health (all p<0.01), with 90% of companies choosing to maintain the shorter week afterward.

A UK scenario analysis found that a national four-day week could reduce car mileage by 9% by cutting weekly commuting miles by 558 million. A 10% reduction in work hours may lead to declines in ecological footprint by 12.1%, carbon footprint by 14.6%, and CO₂ emissions by 4.2%, according to a 2012 study of 29 OECD nations.

Local, Circular Economies Replacing Global Extraction: Circular economy principles turn waste into resources. Roma Grus's new 140-tonne-per-hour waste recycling plant in Sweden processes construction waste into recycled aggregates and sand, significantly cutting carbon emissions. In 2023, Circular Services put over 1 million tons of materials back into production supply chains, avoiding 1.6 million metric tons of emissions.

Local circularity reduces emissions linked to imported goods by 80% in C40 cities. The Petaluma Reusable Cup Project achieved 90%+ positive resident experience, demonstrating strong community pride from local initiatives.

Bhutan's Gross National Happiness Framework: Bhutan introduced Gross National Happiness (GNH) in the 1970s, officially adopting it in 2008. "We consider Gross National Happiness more important than Gross Domestic Product," declared King Jigme Singye Wangchuck in 1972. The framework surveys 133 questions across nine domains: Culture, Time-use, Good Governance, Community Vitality, Living Standards, Health, Education, Environment, and Psychological Well-being.

GNH offers a dual role: philosophical guidance and quantitative policy evaluation. Finance Minister Namgay Tshering developed taxation laws evaluated through the GNH framework to ensure meaningful, sustainable growth. Bhutan maintains that only 1.4% of its land is non-forest, with 85% forest cover.

Yet Bhutan's model reveals tensions. The 2022 GNH survey showed a happiness score of 0.781 - only 3.3% higher than 2015. Youth unemployment reached 28.6%, tourism revenue collapsed during the pandemic (2023 saw only one-third of 2019 visitors), and the planned Gelephu Mindfulness City threatens to displace 10,000 farmers. Critics note Bhutan ranks 90th in press freedom, down from 33rd.

The Bhutanese concept of 'chokkshay' - the knowledge of enough - mirrors degrowth's core idea that contentment can replace endless consumption. But implementation challenges show that wellbeing metrics alone cannot secure sustainable development without addressing systemic economic pressures.

Scandinavia's Circular Economy Revolution: Sweden aims for zero waste through laws and incentives. A 2024 law mandates that everyone - households and businesses - separate food waste, which is converted into biogas to replace fossil fuels. Nearly 3 billion bottles and cans are recycled annually through the 'pant' deposit system - so ingrained that 'panta' is now a Swedish verb.

Producer responsibility legislation from 1994 made businesses responsible for packaging waste collection and recycling, creating market-driven incentives for circular design. In 2017, the government reformed taxes so people could get cheaper repairs on used items. In 2023, Swedish households and businesses generated 4.1 million tonnes of municipal waste (392 kilos per person), with 39% recycled and 59% turned into energy.

In 2024, H&M and Vargas Holding launched Syre, a textile company focusing on polyester-to-polyester recycling, with sales expected to start in 2026. Sweco's report for the Nordic Council recommends targeted fees on fast fashion, VAT reductions for second-hand trade and repair services, and R&D funding for circular business models.

Netherlands' Green Hydrogen Pilots: The Groenvermogen pilot programme supported 12 projects with a €100 million budget. H2 Hollandia produces approximately 300,000 kg of hydrogen per year from surplus solar power. XINTC's smart electronics ensure electrolysers switch on and off at high frequency, maximizing efficiency of renewable energy conversion.

These projects link nearby solar and wind farms directly to hydrogen production and use, creating local, low-carbon fuel cycles that support energy independence.

Business Models Embracing Degrowth: Mud Jeans operates a "Lease A Jeans" programme in the Netherlands, where customers lease rather than buy denim garments, with the company retaining ownership and handling maintenance and recycling.

Buy Me Once is a UK retailer promoting sustainable consumption by offering products designed to last a lifetime, focusing on quality over quantity.

Patagonia's Worn Wear program repaired over 130,000 items in 2024, keeping them out of landfills. 95% of Worn Wear customers reported increased brand loyalty.

Interface's Net-Works initiative collected and processed over 2 million kg of discarded fishing nets, transforming them into carpet tiles through their ReEntry program.

Degrowth combines critiques of capitalism, colonialism, patriarchy, productivism, and utilitarianism into a holistic socio-ecological vision. The core argument: capitalist economic growth inevitably drives continuous production and consumption, directly increasing greenhouse gas emissions and resource extraction.

The Debt Trap Argument: Post-growth advocates argue that debt expansion creates a structural incentive for perpetual growth incompatible with ecological and social limits. The Post Growth Institute claims that total debt always expands in modern capitalist systems, setting us up for economic collapse, while total ecological footprint always expands, setting us up for environmental collapse.

Hans Christoph Binswanger's analysis of the monetary growth imperative argues that the combination of credit money and compound interest creates an inherent need for economic growth. Karl Marx viewed capitalism as unable to stand still, requiring continual expansion to survive through mechanisms of competition and accumulation.

The Decoupling Myth: Degrowth proponents reject the idea that economic growth can be "decoupled" from environmental harm. The European Environmental Bureau stated in 2021 that "there is no empirical evidence supporting the existence of decoupling of economic growth from environmental pressures on the scale needed to address environmental breakdown."

What appears as green growth in high-income nations is largely artificial, achieved by offshoring production and shifting emissions to lower-income countries. Decoupling achieved in wealthy nations is production-based, not consumption-based - goods are made elsewhere, but emissions still occur.

The Innovation Funding Paradox: Critics of degrowth argue that with reduced income, developed countries will have fewer resources for climate mitigation and adaptation technologies. The most innovative countries - USA, Switzerland - have the highest GDPs. But degrowth advocates counter that innovation funding can be redirected from military spending, corporate subsidies, and wasteful consumption.

Modern monetary theory, suggested by Jason Hickel, proposes financing degrowth through sovereign money creation combined with taxation and price controls to mitigate inflation.

The Global South Development Dilemma: Degrowth of high-income countries would destabilize lower-income countries due to economic interdependencies. Low-income economies depend on exports of natural resources to high-income countries. Currently, 63% of global carbon emissions come from developing countries, meaning reducing GDP in wealthy nations has limited effect on global emissions.

With 712 million people still in extreme poverty worldwide, critics argue degrowth risks leaving the poorest behind. The COVID-19 crisis increased poverty in the global south, demonstrating how economic contractions in the North harm developing nations.

Degrowth proponents acknowledge this tension. The movement considers the global south exempt from degrowth, but this creates paradoxes. If wealthy nations reduce consumption while poorer nations continue extraction and pollution, global inequities may worsen. Degrowth must include systemic reforms of global trade, finance, and governance to mitigate risks to the Global South.

Rebound Effects Could Backfire: Degrowth proposals such as basic income and reduced working hours may trigger rebound effects, potentially increasing consumption rather than reducing it. With more leisure time and guaranteed income, people might fly more, drive luxury vehicles, or consume more entertainment - all carbon-intensive activities.

A 2019 U.S. survey found 43% support for UBI, rising to 67% among ages 18-29 but dropping to 40% for those 50-64. Studies from Western countries show UBI recipients reduce labor force participation, which critics argue undermines productivity and economic resilience.

Inflation and Fiscal Pressure: Critics believe UBI would be a massive drain on the economy. Funding it would require huge tax hikes or wealth redistribution, potentially discouraging productivity and innovation. A $1,000 monthly stipend would cost about $3.81 trillion per year - 21% of U.S. GDP.

Funding UBI via reallocation from existing welfare budgets risks depriving vulnerable groups needing specialized support, such as individuals with disabilities or chronic illness. Paul Boyce warns: "A UBI would essentially transfer wealth away from higher earners toward low earners. This spurs higher consumption... Rather than money going toward investment, it is going toward consumer goods," potentially driving inflation.

The Authoritarian Risk: Degrowth may pressure Western democracies toward authoritarianism. Democratic institutions are likely to resist voluntary contraction, potentially reverting to authoritarian governance. The only historical example of a stationary society was Japan's Edo period - a brutal dictatorship.

Degrowth policy proposals risk promoting authoritarian governance by undermining democratic institutions, as citizens accustomed to growth may not voluntarily accept contraction.

The Empirical Uncertainty: Three systematic reviews published between 2023 and 2025 in Ecological Economics showed divergent conclusions due to differing search terms and inclusion criteria. Only three articles on degrowth appear in the top five economics journals, with none directly addressing the concept in high-impact outlets.

Degrowth research remains largely Euro-centric, with limited engagement from mainstream economic journals and persistent reliance on theoretical models. Despite claims of reduced emissions, degrowth's practical impact remains uncertain because it is conceptualized as 'planned reduction' rather than spontaneous recession.

Empirical evidence suggests yes - under specific conditions.

The Work-Life Balance Evidence: The six-month four-day workweek trial demonstrated that income-preserving reduced hours improve workers' well-being across multiple countries. Mediation analysis showed work-ability, sleep, and fatigue as key mechanisms linking hour reduction to wellbeing. Workers felt more satisfied with job performance and reported better mental health after six months than before.

Shortening the workweek enhances mental and physical health, which could improve aggregate societal well-being even with lower economic output. Reduced working hours not only cut transportation emissions but also lower demand for office equipment, materials, and healthcare services.

The Quality-of-Life Frameworks: Bhutan's GNH framework and the Happy Planet Index demonstrate the feasibility of measuring prosperity without GDP growth. The Happy Planet Index, introduced in 2006, uses each country's ecological footprint as an indicator alongside standard wellbeing determinants. The 2012 list was topped by Costa Rica, Vietnam, and Colombia - not wealthy nations.

Five countries - Finland, Scotland, Wales, Iceland, and New Zealand - formed the Wellbeing Economy Governments (WEgo) network in 2020. New Zealand tabled the world's first 'wellbeing budget,' targeting 5% of overall spending to wellbeing initiatives.

The Pandemic Natural Experiment: The COVID-19 pandemic caused a 7% drop in global commercial commerce in 2020. In 2020, there was a sharp decline in emissions largely due to pandemic impacts on travel and economic activity. However, in 2022, U.S. greenhouse gas emissions increased 0.2% compared to 2021, and CO₂ emissions from fossil fuel combustion increased 8% relative to 2020.

This rapid rebound suggests that temporary economic contractions without structural changes cannot deliver sustained climate benefits. A study concluded that the direct effect of the pandemic response on global warming will likely be negligible, but a well-designed economic recovery could avoid future warming of 0.3°C by 2050.

The lesson: a chosen recession must be accompanied by permanent structural reforms - renewable energy investment, circular supply chains, wealth redistribution - or emissions will simply bounce back.

Degrowth requires coordination across political and social strata. Manuel and Mark's debate emphasizes that a dual strategy - combining top-down policy and bottom-up community action - is essential for scaling degrowth.

International Frameworks: Contraction and Convergence (C&C), conceived by the Global Commons Institute in the early 1990s, proposes reducing global emissions to safe levels (contraction) while bringing each country's per-capita emissions entitlement toward equality (convergence).

The model calculates a linear convergence rate, allowing the speed to be set between immediate and future dates. In 2009, the Met Office Hadley Centre agreed that C&C rates projected by GCI to keep within 2°C were better than the UK Government's Climate Act projections.

Critics argue per-capita focus may incentivize countries to boost population to acquire more entitlements. The Global Commons Institute incorporated a population base-year function to address this, limiting benefits of population growth beyond a chosen base year.

Ecosocialist Revolutionary Framework: The 18th World Congress of the Fourth International adopted a manifesto explicitly committing to global degrowth. With 150 delegates from 42 countries, the manifesto states "on a global scale carbon emissions will have to be drastically reduced, otherwise human life will be in mortal danger."

The manifesto outlines specific policies: reduced working hours, massified free public transport, and fundamental rights to water, housing, and health. It positions degrowth within an ecosocialist revolution that includes progressive taxation, public ownership, and systemic anti-capitalist measures.

The International Degrowth Network (IDN) advocates for "radical inclusivity" and "active resistance to systems of domination," calling for the Global South to use "anti-colonial and anti-imperial" actions to liberate itself from Global North imperial dynamics.

Scholarly Consensus Building: A 2025 Lancet Planetary Health review by Giorgos Kallis and colleagues cited 200+ scientific studies to support a post-growth thesis. A 2023 survey of nearly 800 climate-policy researchers found 73% support post-growth (45% agrowth, 28% degrowth).

"We know we're crossing [the boundaries]," said Kallis. "What the economy is doing is transforming matter into goods and services, and that transformation requires energy. If you have economic growth, you're going to use more matter, and you're going to use more energy."

Kallis acknowledged political will as the primary obstacle: "We see that the trends are moving very much in the other direction, so it's not just a matter of doing the analysis."

Mark H Burton frames degrowth as "better collapse" - a proactive transformation rather than reactive disintegration. "We do not expect to win but we cannot afford to lose," he writes. "Our approach will be collective not individual, caring, sharing and resisting, while always showing the way along the alternative degrowth pathway that we will be constructing as we go."

This realism distinguishes degrowth from utopian thinking. Proponents recognize capitalism will resist - Aurora Despierta warns elites may co-opt degrowth rhetoric just as they've greenwashed corporate responsibility.

The Strategic Incrementalism Path: Patrick Loftus proposes that "a brief period of 'green-growth decarbonization' could still serve as the beginning of a larger degrowth transformation." Strategic incrementalism identifies "low-hanging fruit" - public transport investment that reduces both emissions and dependence on mined materials for electric vehicles.

Degrowth should identify incremental opportunities within current institutions to demonstrate proof-of-concept before full structural change. These opportunities have "high decarbonization potential and relatively low implementation barriers."

The Planetary Boundaries Imperative: Six of nine planetary boundaries have been transgressed as of 2023: climate change (CO₂ at 423 ppm versus 350 ppm boundary), biosphere integrity, land-system change, freshwater change, nitrogen cycle, and phosphorus cycle.

"Transgressing one or more planetary boundaries may be deleterious or even catastrophic due to the risk of crossing thresholds that will trigger non-linear, abrupt environmental change within continental-scale to planetary-scale systems," warn the framework authors.

Intentionally reducing economic activity could keep CO₂ emissions below the 350 ppm threshold and return to a climate state compatible with the Holocene, reducing the risk of crossing tipping points.

The Circular Economy Transition Path: Transitioning from a linear economy to a circular economy would net 7 to 8 million jobs globally by 2030 and create 24 million green jobs in the U.S. by 2030, according to estimates.

Reshoring - relocating production back to home countries - facilitates shorter supply chains that reduce transportation-related carbon emissions while enhancing material traceability for closed-loop systems. Case studies across manufacturing sectors show reshored production enables local innovation and adopts advanced technologies like additive manufacturing and digital tracking.

While systemic change requires policy action, individuals can support degrowth principles:

Reduce Work Intensity: Advocate for four-day workweeks in your workplace. The evidence shows productivity can be maintained while improving wellbeing.

Support Circular Businesses: Choose companies offering repair services, leasing models, and lifetime warranties. Patagonia, Interface, and Mud Jeans demonstrate profitability is possible.

Demand Local Procurement: Push your local government to prioritize local suppliers and circular economy initiatives like reusable cup programs.

Vote for Progressive Taxation: Support candidates proposing wealth taxes, capital gains reforms, and UBI pilots.

Educate and Organize: Join organizations like the International Degrowth Network or local environmental justice groups. Share information about wellbeing economics.

Practice Voluntary Simplicity: Embrace Bhutan's concept of 'chokkshay' - the knowledge of enough. Consumption beyond sufficiency doesn't increase happiness.

Challenge Growth Rhetoric: When politicians promise economic growth as the solution to all problems, ask: Growth of what? For whom? At what environmental cost?

The choice before us isn't between growth and poverty, but between intentional transition and chaotic collapse. Degrowth proposes we consciously redesign our economic systems for wellbeing within planetary boundaries rather than wait for ecological catastrophe to force contraction upon us.

The evidence shows a planned recession - with progressive taxation, universal basic income, reduced working hours, and circular economies - can maintain or improve quality of life while cutting emissions. Bhutan's GNH framework, Scandinavia's circular initiatives, and global four-day workweek trials demonstrate these aren't fantasies but implementable policies.

Yet political will remains the bottleneck. Current economic structures, corporate interests, and cultural norms all reinforce the growth imperative. Degrowth's limited presence in mainstream economics journals and policy debates reflects not intellectual weakness but power asymmetries.

The movement's realism is its strength. "We do not expect to win but we cannot afford to lose," as Mark Burton says. Whether called degrowth, post-growth, or wellbeing economics, the fundamental insight remains: humanity would benefit more by aiming for ecological sustainability and staying within planetary limits than pursuing relentless growth.

The question isn't whether economic contraction will happen - climate breakdown and resource depletion make it inevitable. The question is whether we'll choose it consciously, equitably, and democratically, or whether it will be forced upon us through disaster.

A planned recession may be our best chance at a livable future. The alternative is an unplanned one.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

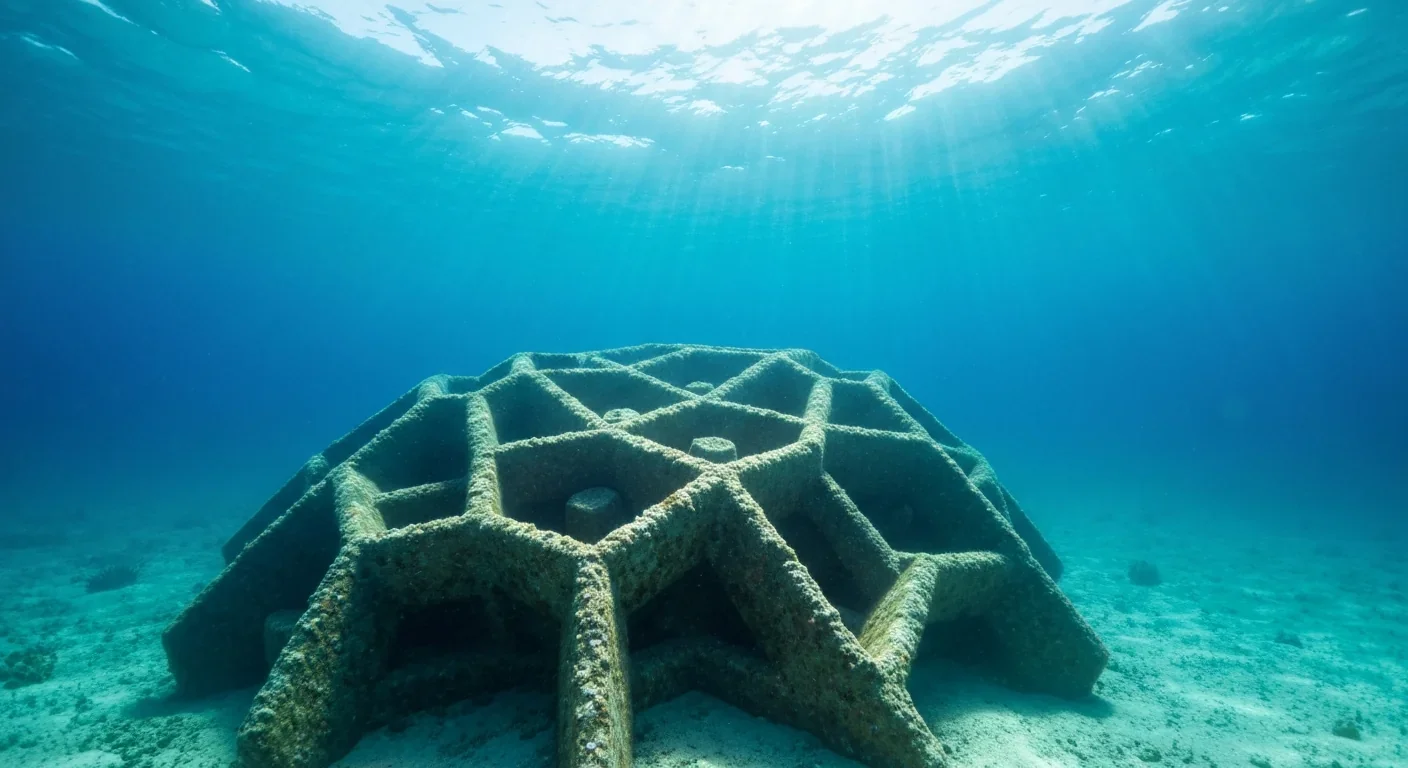

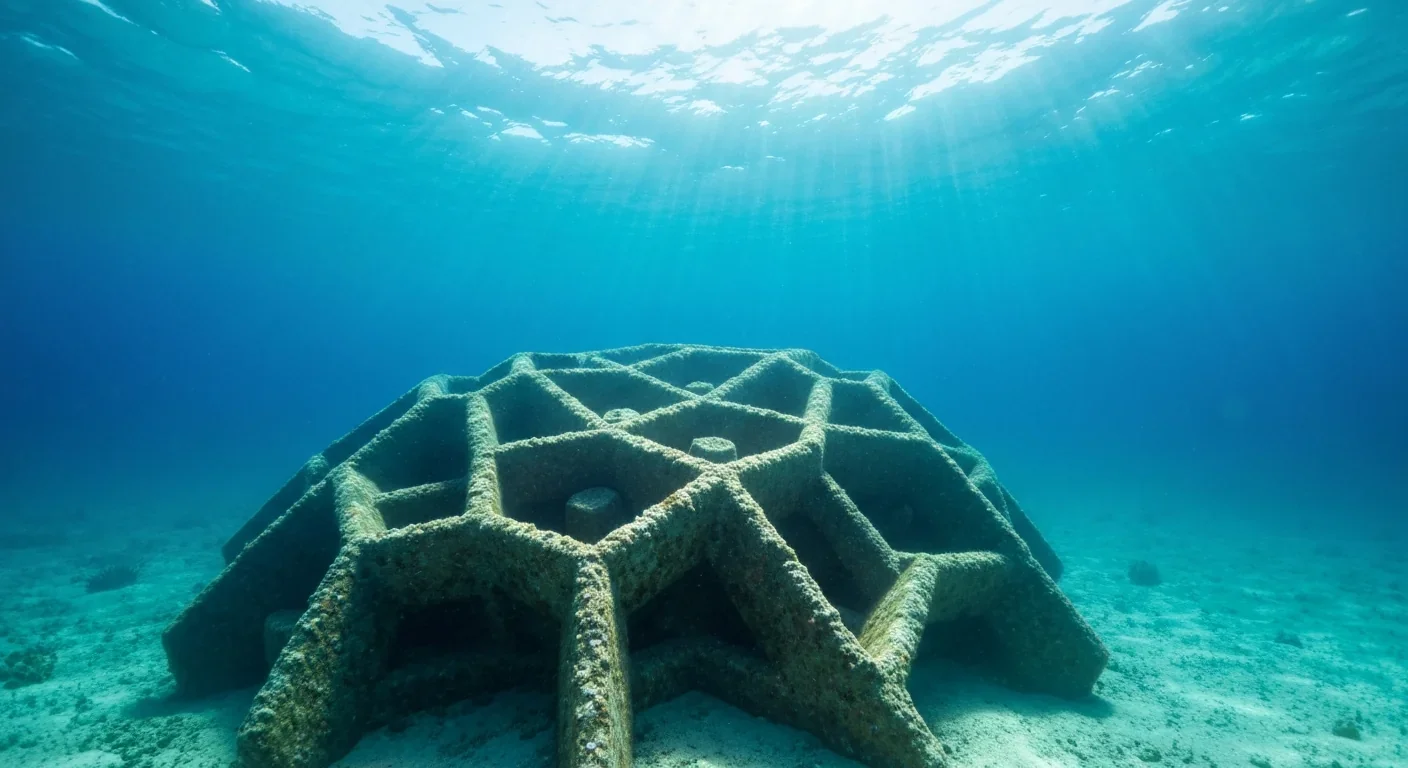

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

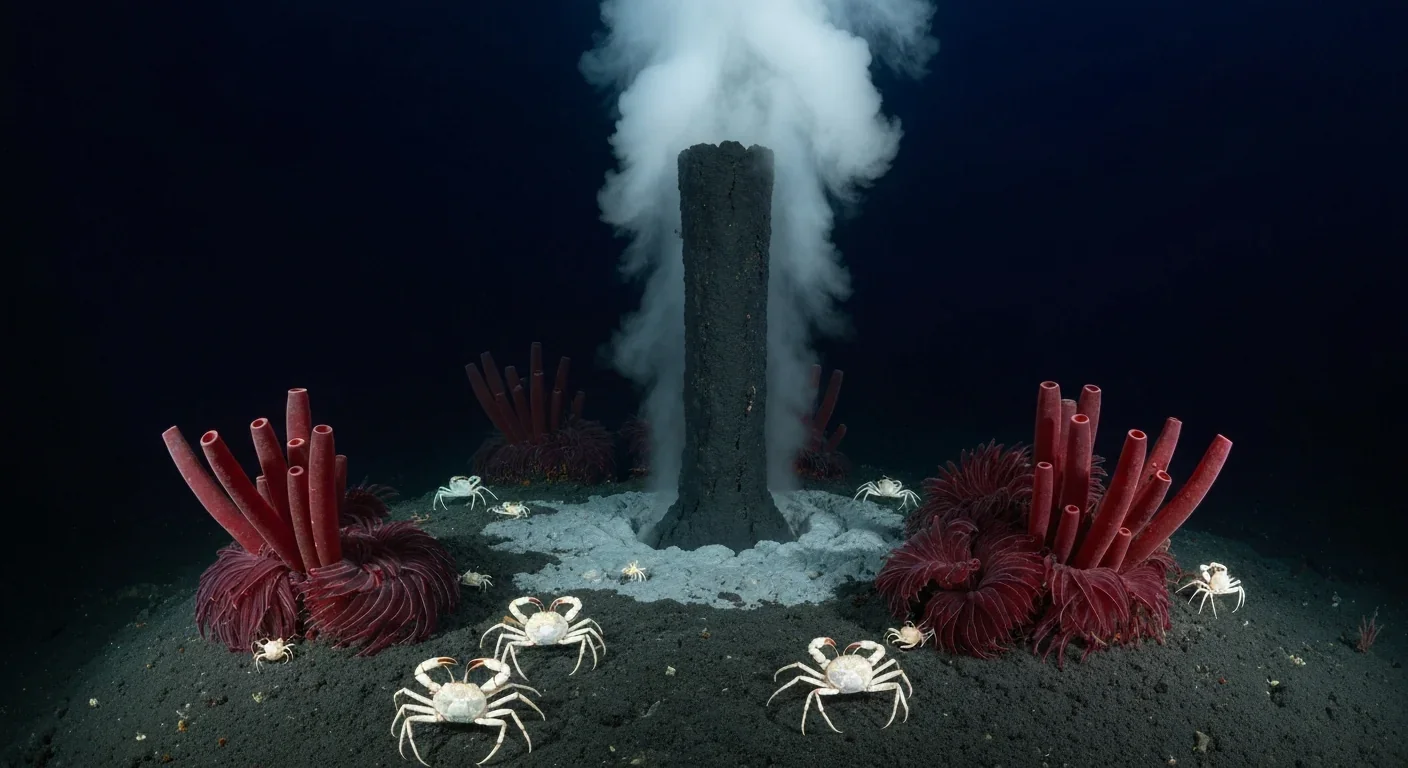

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

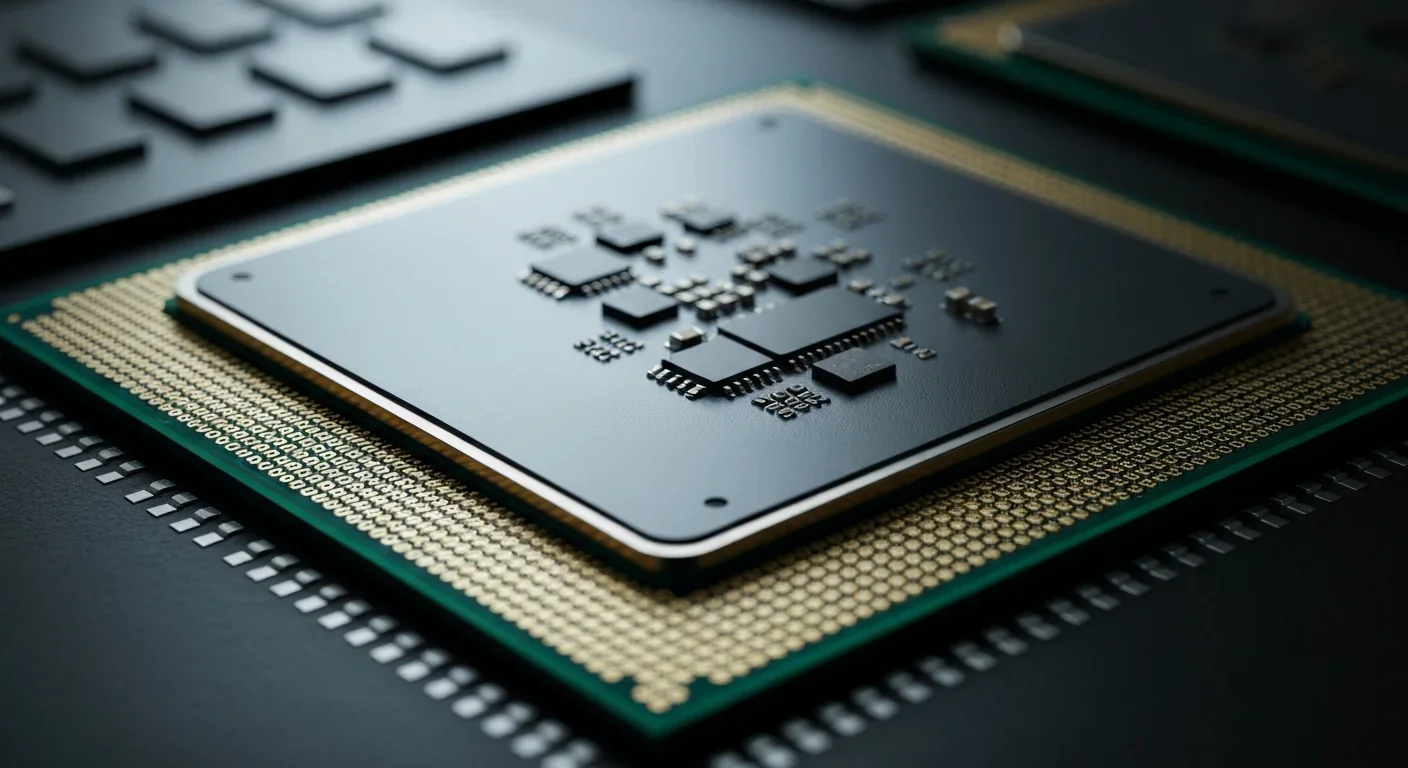

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.