AI Cameras Save Sea Turtles in Fishing Nets

TL;DR: Modular electronics from Framework and Fairphone prove devices can be repairable, upgradable, and long-lasting. New right-to-repair laws are forcing manufacturers to rethink disposable design, though trade-offs in cost and size remain. The future depends on whether consumers value longevity over convenience.

By 2030, the global e-waste mountain will reach 82 million metric tons annually, each kilogram representing a phone discarded because a battery died, a laptop replaced because a port broke, a tablet binned because the screen cracked. But what if your next device was different? What if the broken part could simply be swapped out in minutes, keeping the rest of your tech running for years or even decades? This isn't science fiction anymore. A small group of companies is proving that electronics don't have to be disposable, and their success is forcing the entire industry to rethink how we build, buy, and trash our devices.

Something fundamental shifted in 2024. The European Union adopted sweeping right-to-repair legislation that requires manufacturers to make products easier and cheaper to fix. California, New York, and Colorado followed with their own laws, while Oregon went even further in 2025, banning "parts pairing," the practice where manufacturers use software to prevent third-party or DIY repairs.

These weren't just feel-good regulations. They represented a response to a crisis that was becoming impossible to ignore. In 2022 alone, humanity generated 62 million metric tons of e-waste, with only 17.4% of it properly recycled. The rest ended up in landfills or incinerators, leaching toxic materials into soil and water. The average American generated nearly 7 tonnes of e-waste annually, much of it from devices that could have been repaired but weren't designed to be.

The new laws forced a reckoning. Manufacturers could no longer hide behind proprietary screws, glued-together cases, or deliberately complex designs that made repair impossible for anyone but authorized service centers.

The new laws forced a reckoning. Manufacturers could no longer hide behind proprietary screws, glued-together cases, or deliberately complex designs that made repair impossible for anyone but authorized service centers. They had to provide parts, tools, and documentation. They had to design products people could actually fix.

And so, reluctantly at first, but with growing momentum, the industry started to change.

This wasn't the first time society wrestled with designed obsolescence. In the 1920s, a cartel of lightbulb manufacturers secretly agreed to limit bulb lifespans to 1,000 hours, even though they could easily make bulbs lasting much longer. The Phoebus cartel worked for years, keeping sales high by ensuring products failed on schedule.

By mid-century, planned obsolescence had become business gospel. General Motors popularized the strategy of yearly model changes to make older cars seem outdated. Consumer electronics followed the same playbook. When transistors replaced vacuum tubes in the 1960s, devices became more reliable, but manufacturers compensated by making them harder to repair and cheaper to replace than fix.

The personal computer revolution temporarily reversed this trend. Early PCs were gloriously modular because no single company controlled the entire ecosystem. You could upgrade your RAM, swap your graphics card, replace your hard drive. Hobbyists built machines from components, and repair shops thrived.

But the iPhone changed everything. When Apple released it in 2007, the device was a masterpiece of integration. Every cubic millimeter was optimized. Components were soldered, glued, and nested in ways that made the phone thinner, lighter, and more beautiful, but also nearly impossible to repair without specialized tools and expertise. Other manufacturers copied the approach because consumers clearly valued sleekness and performance over repairability.

The pendulum swung too far. By the 2010s, laptops had batteries you couldn't replace, phones with screens fused to frames, and tablets scored at 1 out of 10 on repairability scales. When something broke, you bought a new one. The entire business model depended on it.

Now, the pendulum is swinging back. Not because companies suddenly developed a conscience, but because laws, consumer pressure, and a handful of insurgent manufacturers proved there was another way.

Walk into any electronics store and most laptops look roughly the same: thin, sleek, sealed shut. The Framework Laptop looks similar until you realize every port is removable. Need USB-C instead of HDMI? Pop out the old module, snap in the new one. Spill coffee on the keyboard? Five screws and it's replaced. Want more storage? The SSD swaps in seconds. Battery degraded after three years? Here's a new one.

iFixit, the repair advocacy group that scores devices on repairability, gave the Framework Laptop a perfect 10 out of 10, the first laptop ever to achieve that score. The newer Framework Laptop 13 got the same score even though it's 15% smaller, proving you don't have to choose between compact design and repairability.

"Modular electronics are offering a practical and adaptable alternative to traditional integrated designs."

- Industry Analysis, Titoma

Framework's approach is radically simple: assume people will want to repair and upgrade their devices, then design accordingly. Use standard screws. Make components easy to access. Publish repair guides. Sell spare parts at reasonable prices. The result is a laptop that can theoretically last decades, with periodic upgrades keeping it current.

Across the Atlantic, Fairphone took a similar philosophy to smartphones. The Dutch company created the world's first modular smartphone designed for longevity and ethical sourcing. The Fairphone 5, released in 2023, features 10 replaceable modules including the battery, camera, USB-C port, and even the speaker. Drop it and crack the screen? A new display costs €99 and takes 20 minutes to install with no special tools.

Fairphone's mission goes deeper than just repairability. The company sources conflict-free minerals, pays fair wages to factory workers, and designs for an eight-year lifespan with software updates to match. It's a direct challenge to the smartphone industry's two-year replacement cycle.

Both companies remain small compared to giants like Apple and Dell, but their influence far exceeds their market share. They proved modularity could work. They showed consumers cared. And they forced larger manufacturers to at least pretend to care about repairability.

If modular design is so great, why don't all electronics work this way? Because engineering is about trade-offs, and modularity comes with real costs.

Size and weight: Connectors take up space. A soldered component sits flush against the motherboard. A modular component needs a socket, retention mechanism, and space for fingers to grip it. Multiply that across dozens of components and your device grows noticeably thicker and heavier. In a world where customers obsess over millimeters and grams, that's a tough sell.

Cost: Connectors, fasteners, and reinforced frames add 15-30% to manufacturing costs, according to electronics manufacturing analysts. A modular phone might cost $200 more to produce than an equivalent integrated device. Manufacturers can pass some of that to consumers, but price-sensitive markets resist.

Reliability: Every connector is a potential failure point. Dust gets in. Contacts corrode. Mechanical stress loosens connections. A well-designed integrated product can actually be more reliable than a modular one, especially in harsh environments. That's why military and industrial applications often favor sealed, integrated designs despite repair challenges.

Performance: High-speed data connections work best when signals travel minimal distances. Gaming laptops and professional workstations achieve peak performance through tight integration of CPU, GPU, and memory. Modularity can introduce latency or signal degradation.

Waterproofing: Creating a water-resistant seal around a fixed component is straightforward. Creating one around a removable component that users might swap repeatedly is genuinely difficult. Apple's engineers will tell you (correctly) that gluing everything together helped achieve the IP68 water resistance consumers expect.

These aren't hypothetical concerns. Google's Project Ara, an ambitious effort to create a fully modular smartphone, collapsed in 2016 partly because the engineering challenges proved insurmountable at consumer-friendly price points.

These aren't hypothetical concerns. Google's Project Ara, an ambitious effort to create a fully modular smartphone, collapsed in 2016 partly because the engineering challenges proved insurmountable at consumer-friendly price points. You could technically make a phone where every component was swappable, but it would be thick, expensive, and fragile.

The question isn't whether trade-offs exist, it's whether they're worth it. Framework and Fairphone argue you can find a sweet spot where devices are modular enough to be repairable without being ridiculously bulky or expensive. The market seems to agree, at least for a growing niche.

Repairable electronics sound environmentally friendly, but do the numbers support the intuition? It depends how you calculate.

The straightforward case is easy. If you use a laptop for eight years instead of four because you can replace the battery and upgrade the RAM, you've cut your environmental impact in half. Manufacturing accounts for roughly 70-80% of a device's total environmental footprint, so using it longer dramatically reduces your per-year impact.

But the calculus gets complicated. A 2024 academic study in Frontiers in Sustainability found that for smartphones, the manufacturing emissions associated with creating a modular device can be 20-25% higher due to additional materials and complexity. If users don't actually keep the device longer, you've made things worse, not better.

The environmental benefit materializes only when people actually use the repairability features. If consumers buy a Framework Laptop but replace it after four years anyway because they want the latest processor, the extra manufacturing emissions weren't worth it. The system depends on changing behavior, not just technology.

That said, the potential is enormous. Americans could save $40 billion annually if they repaired devices instead of replacing them, according to consumer advocacy groups. The US alone generates 6.9 million tonnes of e-waste yearly. If even a quarter of that could be avoided through repair, you'd eliminate nearly 2 million tonnes of waste, along with all the mining, manufacturing, and shipping emissions required to create replacement devices.

The circular economy potential extends beyond just repair. Modular devices enable easier recycling because components can be separated rather than shredded together. Specialized refurbishers can harvest working modules from damaged devices and recombine them into functional units, something nearly impossible with integrated electronics.

Perhaps most important, modular design changes manufacturing supply chains. When a component goes obsolete or becomes unavailable, an integrated device requires complete redesign. A modular device just needs a new version of that one module. This reduces waste throughout the production chain and makes businesses more resilient to supply chain disruptions like the chip shortages of 2021-2023.

Consumer surveys reveal a paradox. A Windows Report survey found that 57% of people want the freedom to repair devices at home, and 89% see e-waste as a major concern. Yet repair rates remain stubbornly low.

Convenience: Taking your laptop to a repair shop or spending 30 minutes replacing a module yourself will always be less convenient than clicking "buy now" on a replacement. Modern life runs on convenience, and even simple repairs require time and motivation most people lack.

Knowledge gaps: Many consumers don't realize their devices can be repaired. They assume a cracked screen means a dead phone. Manufacturers have actively cultivated this perception for years by making repair seem difficult or risky.

Cost calculations: Authorized repairs are often priced at 60-80% of a new device's cost, making replacement seem logical. A $300 screen replacement on a $400 phone makes no economic sense, even though the actual repair cost for parts and labor should be under $100.

Fashion and features: Let's be honest - people like new things. New devices come with better cameras, faster processors, and new colors. Keeping your old laptop running might be environmental, but it's not exciting. Tech companies spend billions cultivating the desire for the latest model.

"We face significant barriers to fix many products - barriers imposed by the manufacturers."

- Washington repair shops action letter

Network effects: If nobody you know repairs their devices, you won't either. Repair culture has to reach critical mass before it feels normal rather than eccentric. Right now, walking into a café with a 6-year-old phone marks you as either very practical or very broke, not as environmentally conscious.

The right-to-repair legislation addresses some of these barriers by forcing manufacturers to offer parts at reasonable prices and provide repair documentation. But laws can't make repair cool or convenient. That requires cultural change.

Early signs suggest the change is happening, slowly. iFixit reports that their repair guide traffic has grown 40% year-over-year since 2020. YouTube repair videos get millions of views. Reddit communities like r/repair_tutorials have hundreds of thousands of members. A generation of users is learning that fixing things is empowering, not intimidating.

The modular electronics movement isn't winning on altruism. It's winning because real business models support it, and real money is at stake.

Independent repair shops are the most obvious beneficiaries. Right-to-repair laws legitimize their existence and guarantee access to parts and information. The consumer electronics repair market was valued at $27 billion in 2023 and is projected to reach $43 billion by 2032, growing 5.8% annually. Every device that can be repaired instead of replaced feeds this ecosystem.

Consumers benefit from lower total cost of ownership. Framework openly publishes cost comparisons showing their laptops cost less over five years than comparable devices from Apple or Dell once you account for repair and upgrade savings. A battery replacement costs $89 instead of $400 at an Apple store. Storage upgrades cost 50% less than buying a higher-spec model initially.

Manufacturers might seem like losers in this scenario, but forward-thinking companies see opportunity. Selling replacement modules creates recurring revenue without the overhead of full device manufacturing. Framework's marketplace for modules and upgrades generates ongoing income from existing customers rather than requiring constant new customer acquisition.

Component suppliers win because modularity increases demand for standardized parts. Instead of each manufacturer using custom SSDs soldered to motherboards, modular laptops use industry-standard M.2 drives, expanding the market for suppliers.

Employers and institutions appreciate modularity for fleet management. If you manage 1,000 laptops, being able to quickly swap a failed module instead of shipping the entire unit for repair or replacement saves enormous time and money. Intel has advocated for modular PC design partly because corporate customers want it.

Environmental compliance is increasingly expensive for companies. Extended producer responsibility laws are spreading, making manufacturers pay for recycling the products they sell. Devices that last longer and generate less waste reduce these costs. Several academic studies have found that modularity reduces total lifecycle costs for producers when all regulatory and disposal costs are included.

The economics work if your business model values customer lifetime value over short-term sales volume. Framework raised $18 million in Series A funding and sells thousands of units monthly, proving investor confidence. Fairphone has survived over a decade and released five phone generations. Neither company is threatening Apple or Samsung yet, but both are profitable and growing.

The repair movement looks different around the world, shaped by local economics and culture.

Europe leads on legislation. The EU's right-to-repair directive and aggressive e-waste regulations reflect a culture that values sustainability and consumer protection. European consumers pay more for products but expect them to last longer. Fairphone, appropriately, is based in Amsterdam.

United States shows a split personality. States like California and New York pass strong repair laws, while federal action remains stalled. American culture values convenience and newness, but also rugged individualism and self-reliance. The DIY repair community is strong and vocal, though still a minority.

East Asia presents a paradox. Countries like Japan and South Korea produce much of the world's consumer electronics but have weak repair cultures at home. New devices are status symbols; keeping old ones suggests financial struggle.

East Asia presents a paradox. Countries like Japan and South Korea produce much of the world's consumer electronics but have weak repair cultures at home. New devices are status symbols; keeping old ones suggests financial struggle. However, repairability scores are starting to matter in these markets as younger consumers become more environmentally conscious.

Africa, Latin America, and South Asia have robust informal repair economies by necessity. When a new smartphone costs three months' wages, people repair. Street vendors fix phones with improvised tools and salvaged parts. These regions may leapfrog wealthy nations in repair culture because they never developed the disposable mindset. But they lack the regulatory frameworks to force manufacturers to support repair officially.

China is fascinating. As the world's largest electronics manufacturer, Chinese companies could easily embrace modular design - or resist it to protect existing business models. Recent signs point toward openness. Companies like Lenovo and Huawei are experimenting with modular laptops for business markets, though consumer products remain sealed.

The movement toward repairability will succeed globally only if different regions learn from each other. Europe's regulatory frameworks, America's DIY culture, and Asia's manufacturing expertise need to converge into global standards that make modular design the default rather than the exception.

The transition to modular electronics is happening, but it won't be instant or automatic. You can accelerate it.

Vote with your wallet. When buying electronics, prioritize repairability. Check iFixit's repairability scores before purchasing. Fairphone, Framework, and a growing list of others are proving consumer demand matters. Every purchase signals to manufacturers what you value.

Learn basic repair skills. You don't need to be an engineer. Replacing a phone battery or laptop RAM takes 15 minutes and requires only YouTube and basic tools. iFixit offers free repair guides for thousands of devices. Each successful repair builds confidence and saves money.

Support right-to-repair legislation. Check if your state or country has pending repair bills. Consumer advocacy groups like PIRG make it easy to contact legislators with one click. Laws matter - they change what's possible.

Challenge planned obsolescence. When a manufacturer claims a device can't be repaired, ask why. Post online. Leave reviews. Companies care about reputation. Public pressure works.

Extend device lifespans. The environmental benefit of modular design only materializes if you actually keep devices longer. Before replacing a working device, honestly ask whether you need the upgrade or just want it. Maybe the answer is want, and that's okay sometimes. But consciousness matters.

Support local repair shops. They're not just fixing your stuff - they're building the infrastructure for a circular economy. Repair shops create local jobs that can't be outsourced and keep money in communities.

Push for standardization. The beauty of modular PCs in the 1990s was interchangeable components. We need industry standards for laptop batteries, phone screens, and other common components. Write to manufacturers asking them to adopt standards. Join or support organizations advocating for interoperability.

Modular electronics won't kill the throwaway tech era overnight. Integrated designs have real advantages for certain applications, and consumer behavior changes slowly. But the trajectory is clear.

Right-to-repair laws are multiplying. The embedded module market for modular components is projected to grow 12% annually through 2030. Major manufacturers who ignored repair for years are suddenly releasing repair manuals and selling spare parts. Apple, the company that pioneered irreparable design, now offers self-service repair programs for some devices (though critics note the programs are deliberately complicated).

The next decade will determine whether modularity becomes mainstream or remains a niche. Market research firms project the repair services market could triple by 2035 if current trends continue. But that requires sustained consumer demand, continued regulatory pressure, and technological breakthroughs that minimize the trade-offs.

We're not going back to 1990s PCs, bulky and beige. The future is devices as beautiful and powerful as today's, but designed with repair in mind from the first sketch. Manufacturers are starting to realize that "repairability can be a feature, not a compromise", as one industrial design firm put it.

The question is no longer whether we can design electronics that last. Framework and Fairphone proved we can. The question is whether we will - whether consumers, companies, and governments choose longevity over convenience, repairability over sleekness, sustainability over quarterly profits.

The answer is emerging, one replaced battery at a time. The throwaway tech era isn't dead, but it's starting to look mortal. And what comes next might actually be built to last.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

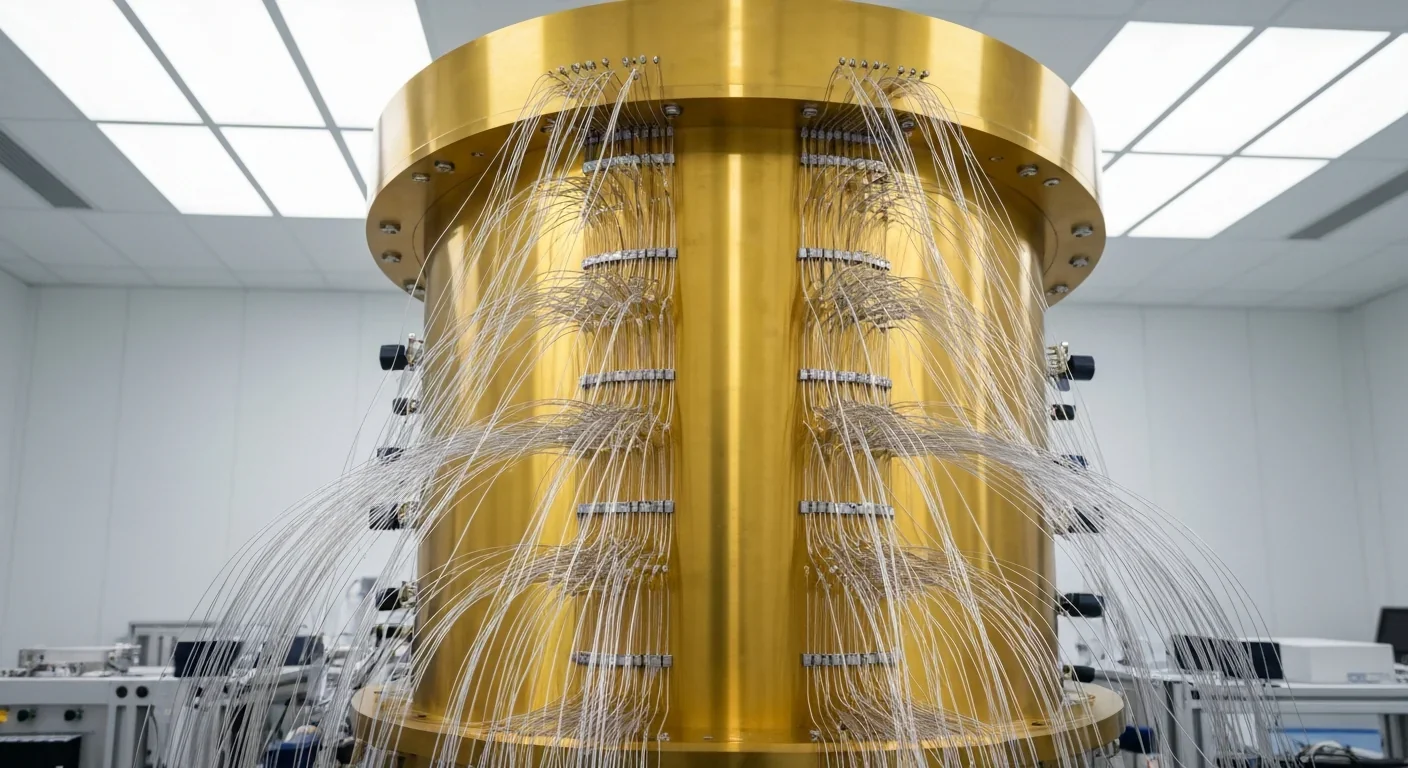

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.