AI Cameras Save Sea Turtles in Fishing Nets

TL;DR: AI-powered robots are revolutionizing recycling by sorting materials 10x faster than humans with unprecedented accuracy, reducing contamination by 40%, and making previously uneconomical materials profitable to recover - transforming waste management economics while cutting global emissions.

The recycling bin has been a symbol of environmental responsibility for decades, but there's a dirty secret the industry doesn't advertise: traditional mechanical recycling is astonishingly inefficient. Contamination rates at facilities regularly hit 25%, meaning a quarter of what gets sorted ends up in landfills anyway. Human sorters, working at breakneck speed, can only process 50 to 80 items per hour while making countless judgment calls about materials they glimpse for mere seconds. This bottleneck has plagued recycling economics for generations, making many materials too expensive to recover and dooming promising recyclables to incinerators. But walk into a modern materials recovery facility today, and you'll witness something radically different: AI-powered robotic arms moving with inhuman precision, identifying and sorting up to 1,000 items per hour with accuracy that borders on supernatural.

This is Mechanical Recycling 2.0, and it's rewriting the economics of waste management from the ground up.

The robots transforming recycling facilities don't just move faster than humans - they see differently. Modern waste sorting systems combine multiple vision technologies that work together like a high-tech detective squad. High-resolution cameras capture images of materials moving on conveyor belts at speeds that would blur to human eyes. Near-infrared spectroscopy identifies plastic types by analyzing how different polymers reflect light - distinguishing PET from HDPE from polypropylene in milliseconds. Some advanced systems even use hyperspectral imaging, which analyzes hundreds of wavelengths simultaneously to detect material composition with laboratory-grade precision.

But the real magic happens in the machine learning algorithms processing all this data. These AI systems have been trained on millions of images, learning to recognize materials from countless angles, in various states of degradation, covered in labels, crushed, or partially obscured. Where a human sorter might hesitate when encountering a crumpled aluminum can with a plastic cap still attached, AI vision systems analyze the object in 111 different categories simultaneously, making split-second decisions about optimal sorting.

AI robots can process up to 1,000 items per hour with 95%+ accuracy - more than 10 times faster than human sorters while maintaining superior precision.

The physical manipulation comes from robotic arms equipped with specialized grippers. Companies like AMP Robotics have developed gripping systems that can handle everything from lightweight plastic films to heavy glass bottles, adjusting grip pressure and approach angle based on what the vision system identifies. These robots work tirelessly, making 70 to 80 picks per minute without fatigue, bathroom breaks, or the respiratory issues that plague human sorters exposed to dust and contaminants.

The integration of these technologies represents a fundamental shift. Traditional optical sorters could identify materials but relied on air jets to separate them - a method that works well for rigid containers but fails miserably with flexible films or small items. Robotic systems physically grasp and place items, enabling recovery of materials that were previously considered uneconomical to sort.

The application of robotics to waste sorting didn't emerge from the recycling industry itself - it migrated from automotive manufacturing and warehouse automation. But the challenges proved vastly different. Assembly line robots work in controlled environments with predictable objects arriving in known orientations. Waste streams are chaos incarnate: crumpled containers, tangled materials, liquids, food contamination, and infinite variation in size, shape, and condition.

Early attempts at automated waste sorting in the 1990s relied on basic optical sensors that could distinguish a few material types. These systems worked adequately for single-stream recycling of clean, dry containers but struggled with the messy reality of municipal waste. The breakthrough came when machine learning advanced enough to handle uncertainty and variation - when algorithms could be trained to recognize "aluminum can" across thousands of variations rather than requiring exact matches to predetermined templates.

Google's partnership with recycling facilities demonstrated the power of applying tech-industry machine learning expertise to waste sorting. By training neural networks on massive datasets of waste imagery, they achieved recognition accuracy that exceeded human performance in controlled tests. This wasn't just incremental improvement - it was a paradigm shift that made previously impossible sorting tasks suddenly viable.

"Artificial intelligence will revolutionise recycling by enabling facilities to recover materials that were previously too expensive or difficult to sort."

- ZenRobotics research summary

The historical parallel is striking. Just as the printing press democratized information by making copying exponentially faster and cheaper, AI sorting systems are democratizing material recovery by making it economically feasible to recycle materials that were previously too expensive to process. Rare plastics, multi-layer packaging, small metal components - all become recoverable when sorting costs plummet.

The transition from prototype to production has happened with remarkable speed. AMP Robotics alone raised $91 million in late 2024 to accelerate deployment, signaling investor confidence that this technology is ready for scale. Their systems are already operating in facilities across North America, processing millions of tons of recyclables annually.

In Seattle, an Amazon-backed startup deployed AI robots that increased aluminum recovery rates by 30% in the first six months of operation. The facility now captures lightweight aluminum foil and crushed cans that previously escaped to landfills because human sorters couldn't reliably spot them on fast-moving conveyor belts. This wasn't theoretical improvement measured in lab conditions - it was tons of valuable material redirected from waste streams to manufacturing feedstock.

Chicago provides another compelling case study. A recycling plant using AI and robotics reported that contamination rates dropped from 23% to 14% after installation, a reduction that dramatically improved the value of their sorted materials. Lower contamination means better prices from manufacturers who buy recycled feedstock, directly improving facility economics. The plant also reported a 35% decrease in worker injuries, as robots took over the most hazardous sorting positions where workers are exposed to sharp objects, broken glass, and hazardous materials.

Waste Robotics developed plug-and-play systems specifically designed for retrofitting existing facilities. Instead of requiring complete facility redesigns that cost millions, their modular robots can be integrated into current operations for a few hundred thousand dollars. This dramatically lowers the barrier to entry, enabling smaller regional facilities to access technology previously available only to major metropolitan sorting centers.

Facilities integrating AI sorting report contamination reductions of nearly 40% and efficiency improvements of 60%, with payback periods of just 18 to 36 months.

The numbers are compelling. Facilities integrating AI sorting report 60% increases in overall efficiency, processing substantially more material with the same footprint. The reduction in contamination - nearly 40% in many cases - transforms economics. When contamination drops, the value of sorted materials rises, often by enough to cover the cost of the robotic systems within 18 to 36 months.

The financial case for robotic sorting initially seems counterintuitive. Why invest hundreds of thousands or millions in automation when human labor is readily available? The answer lies in the total cost equation.

Human sorters require wages, benefits, training, protective equipment, workers' compensation insurance, and management overhead. Turnover rates in the industry are notoriously high - the work is physically demanding, monotonous, and exposes workers to unpleasant and sometimes hazardous conditions. Recruiting and training replacements costs money and creates periods of reduced productivity.

Robots, by contrast, work 24/7 with minimal supervision. Maintenance costs are predictable and scheduled. There's no turnover, no sick days, no degradation in performance during night shifts or summer heat waves. When EverestLabs analyzed the economics, they found that robotic systems typically achieve payback within three years even before accounting for improved material recovery and reduced contamination.

The real economic transformation comes from recovering materials that were previously uneconomical. Every percentage point improvement in recovery rates translates directly to revenue. Aluminum, for instance, has high intrinsic value - but only if it's captured and sorted with minimal contamination. Robotic systems that boost aluminum recovery by 20 to 30% can generate enough additional revenue to justify their cost on aluminum alone, with all other material improvements representing pure upside.

Market analysts project the waste sorting robots market will grow from $180 million in 2025 to over $450 million by 2030, representing a compound annual growth rate exceeding 20%. This isn't speculative growth driven by hype - it's grounded in facilities seeing genuine return on investment and expanding their automation as a result.

The economics also benefit from network effects. As more facilities adopt AI sorting, the machine learning models improve. Companies like Greyparrot reported detecting and classifying 40 billion waste objects in 2024 alone, with each detection making their algorithms marginally better at handling edge cases and unusual materials. This creates a virtuous cycle where early adopters benefit from continuous improvement without additional investment.

The environmental implications extend far beyond the recycling facility. Higher recovery rates and lower contamination enable true circular economy loops that were previously theoretical.

Consider plastics. Contaminated mixed plastic waste typically gets downcycled into low-grade applications or incinerated for energy recovery. Clean, properly sorted plastics can be recycled back into food-grade containers or technical applications, displacing virgin petroleum-based production. AI sorting systems that can distinguish between PET, HDPE, PP, PS, and PVC with 95%+ accuracy enable closed-loop recycling that genuinely reduces raw material extraction.

The impact on metals recovery is equally significant. Aluminum recycling saves 95% of the energy required for primary production from bauxite ore. But that benefit only materializes if the aluminum is actually recovered and sorted cleanly enough for manufacturers to use. Robotic systems that increase aluminum recovery from 60% to 85% don't just improve by 25 percentage points - they deliver an additional 42% of material that would otherwise require energy-intensive primary production.

"Widespread adoption of AI sorting could reduce global carbon emissions by 50 to 100 million tons annually by 2030 - equivalent to removing 10 to 20 million cars from roads."

- Columbia University Climate Analysis

Some advanced applications extend beyond traditional recycling facilities. Researchers deployed AI-equipped bins in office buildings and public spaces that identify and sort materials at the point of disposal, eliminating contamination before materials even enter the waste stream. When the bin itself becomes an AI sorting agent, recycling rates in trial programs jumped from 30% to 70% because users couldn't contaminate streams even if they tried.

The climate implications are substantial. A Columbia University analysis estimated that widespread adoption of AI sorting could reduce global carbon emissions by 50 to 100 million tons annually by 2030 - equivalent to removing 10 to 20 million cars from roads. This comes from increased recycling displacing virgin material production, which is typically far more energy-intensive than processing recyclables.

Ocean plastic presents another frontier. Researchers developed an AI-enabled system for the Hudson River that uses floating pontoons equipped with cameras and robotic arms to capture and sort waste before it reaches the ocean. The system, funded by a $2.7 million NOAA grant, can identify and categorize plastic debris in real-time, prioritizing recovery of materials most harmful to marine ecosystems.

Despite impressive capabilities, AI sorting systems face real constraints that temper utopian expectations.

Material identification remains imperfect, especially for composite materials or items with multiple components. A yogurt container with an aluminum foil lid, paper label, and plastic base presents challenges. Should it be sorted as plastic? Aluminum? Contaminated waste? Human sorters can make contextual judgments based on facility capabilities and downstream requirements. AI systems follow programmed hierarchies that may not optimize for specific facility economics.

Small objects present physical challenges. Items smaller than a credit card often fall through conveyor gaps or are too difficult for robotic grippers to manipulate reliably. Flexible films - plastic bags, shrink wrap, bubble wrap - can wrap around equipment or confound vision systems that work best with rigid, three-dimensional objects. Some facilities address this by using specialized robotic systems designed specifically for films and flexibles, but this requires additional investment.

Environmental conditions affect performance. Dust, moisture, variable lighting, and temperature swings all impact vision system accuracy. Facilities need climate control and regular cleaning protocols to maintain optimal performance - expenses that erode some of the cost advantages versus human labor, which adapts naturally to imperfect conditions.

The algorithms themselves can embed biases. If training data predominantly features North American packaging, the system may struggle with products from other regions that use different materials, colors, or labeling conventions. International deployment requires retraining on locally relevant datasets, adding complexity for companies operating across multiple markets.

Capital costs, while increasingly competitive, still represent significant barriers for smaller operations. A fully automated sorting system can cost $500,000 to $5 million depending on scale and sophistication. Facilities processing less than 50 tons daily may struggle to justify the investment, potentially creating a technology divide where large urban facilities automate while rural and regional facilities remain labor-intensive.

Maintenance requires specialized expertise. When a human sorter calls in sick, you hire a temp. When a robotic system malfunctions, you need technicians familiar with industrial robotics, machine vision, and AI systems - skills in short supply in many regions. This creates dependencies on equipment vendors that can be problematic if a manufacturer exits the market or fails to provide adequate support.

The most intriguing development is the synergy between advanced mechanical sorting and emerging chemical recycling technologies. Chemical recycling breaks plastics down to molecular building blocks, enabling recycling of contaminated or mixed plastics that mechanical recycling can't handle.

AI sorting systems can dramatically improve chemical recycling economics by pre-sorting materials into optimal feedstock streams. While chemical processes can theoretically handle mixed plastics, they work most efficiently with relatively homogenous inputs. A robotic sorter that separates mixed plastics into polyolefin-rich and polyester-rich streams enables chemical recyclers to optimize process conditions for each stream, improving yields and reducing energy consumption.

This creates a tiered recycling hierarchy. The highest-quality materials get mechanically recycled back into comparable applications. Mid-grade materials get chemically recycled into virgin-equivalent feedstock. Only truly contaminated or non-recyclable materials proceed to energy recovery or landfill. Facilities implementing this approach report overall recycling rates exceeding 90%, compared to 60 to 70% for traditional mechanical-only operations.

Adoption patterns vary dramatically by region, shaped by economics, policy, and existing infrastructure.

Europe leads in deployment, driven by aggressive recycling targets and extended producer responsibility policies that make manufacturers financially responsible for end-of-life product management. Countries with landfill bans find AI sorting particularly attractive because improving recovery rates directly reduces expensive waste-to-energy or export costs. Finland's ZenRobotics pioneered heavy waste sorting robots specifically for construction and demolition debris, demonstrating that the technology applies beyond municipal solid waste.

North America is in rapid catch-up mode, accelerated by Extended Producer Responsibility legislation in states like California, Oregon, and Maine. Facilities are upgrading to meet stricter recycling targets and quality requirements, with AI sorting central to many upgrade plans. Private equity and venture capital are flowing into recycling technology at unprecedented levels, viewing automation as key to improving what has historically been a low-margin, operationally challenging business.

Asia presents a mixed picture. Japan leads in deploying sophisticated sorting for electronics waste, using robotic systems that can disassemble complex devices to recover rare earth elements and precious metals with precision impossible for human workers. China's waste import ban paradoxically accelerated domestic automation as the country built out infrastructure to process its own waste rather than exporting it. India and Southeast Asian countries are earlier in adoption curves, though pilot projects show promising results.

Developing nations face unique challenges. Labor costs that make automation uneconomical in high-income countries may be even more pronounced where manual sorting wages are lower. However, some regions are leapfrogging directly to AI systems to meet growing waste volumes that would require unmanageably large manual sorting workforces. Rwanda's Kigali uses AI sorting in a new facility that processes waste for a city growing too rapidly for traditional labor-intensive approaches to keep pace.

The trajectory is clear: waste sorting is becoming increasingly automated, intelligent, and integrated. Several trends will shape the next decade.

Miniaturization and cost reduction will make the technology accessible to smaller facilities. Companies are developing compact robots specifically designed for limited spaces and lower throughput, targeting the 70% of recycling facilities that process less than 100 tons daily and currently can't justify full-scale automation.

AI capabilities will continue advancing. Current systems identify materials; next-generation systems will predict maintenance needs, optimize sorting strategies in real-time based on downstream market conditions, and even provide actionable feedback to product designers about which packaging designs are most recyclable in practice versus theory.

Integration with municipal smart city infrastructure represents another frontier. Imagine waste bins that communicate fill levels and contamination data to collection trucks that optimize routes in real-time, delivering sorted materials directly to appropriate facilities. The Internet of Things meeting AI sorting could optimize the entire waste value chain, not just individual facilities.

The most transformative potential lies in redesigning products for automated recycling. As AI sorting becomes universal, manufacturers can design packaging that machines read easily, incorporating visual markers or material compositions optimized for robotic identification. This closes the loop: products designed for the sorting systems that will eventually process them, rather than forcing machines to handle packaging designed without recycling in mind.

Policy will accelerate adoption. Extended Producer Responsibility schemes make manufacturers pay for recycling, creating incentives to fund facility upgrades. Recycling mandates and landfill restrictions force municipalities to achieve targets only possible with advanced sorting. Subsidies and tax incentives in several jurisdictions specifically support automation investments, recognizing the public benefit of improved resource recovery.

This transformation creates both opportunities and dislocations. Recycling facility workers will need to evolve from manual sorters to robot supervisors and maintenance technicians - roles requiring different skills but potentially offering better wages and working conditions. Retraining programs will be essential to ensure workers aren't left behind as the industry automates.

For businesses, the message is clear: recycling is becoming more capable and cost-effective. Product designs and packaging decisions should account for AI sorting capabilities, optimizing for machine readability rather than human handling. As recovery rates improve, designing for recyclability translates more reliably into actual recycling rather than wishful thinking.

Consumers benefit from simpler recycling. As AI bins proliferate in public spaces, the burden shifts from "did I sort this correctly?" to simply disposing in designated receptacles and letting machines handle the complexity. This could finally deliver on recycling's original promise: environmental responsibility without requiring expertise to navigate confusing and inconsistent sorting rules.

Investment opportunities abound. Companies developing AI sorting technology, facilities upgrading infrastructure, manufacturers using recycled feedstock, and even real estate near automated recycling facilities all stand to benefit from this industrial transformation. The billions flowing into recycling technology represent bets that automation will finally make the industry consistently profitable while delivering environmental benefits.

The bigger story is what this tells us about technology and sustainability. For decades, environmentalism and economic efficiency seemed at odds - doing the right thing cost more. AI sorting demonstrates that advanced technology can align environmental and economic incentives. Making recycling more efficient doesn't require sacrifice; it requires better tools. That's the paradigm shift with implications extending far beyond waste sorting.

We're witnessing the emergence of an industrial sector that functions more like biology than traditional manufacturing. Natural ecosystems don't generate waste - every organism's output becomes another's input in efficient nutrient cycles. Mechanical Recycling 2.0, enabled by AI, brings industrial material flows closer to that biological ideal. Perfect circularity remains distant, but the gap is narrowing.

The robots sorting through our waste aren't just machines performing tasks humans would rather avoid. They're the infrastructure of a circular economy, the enablers of material loops that economic and technical constraints previously made impossible. As they multiply across facilities worldwide, they're quietly rewriting the fundamental economics of resource consumption.

That aluminum can you toss in the recycling bin has a better chance than ever of actually becoming another aluminum can rather than landfill. The plastic bottle might genuinely return as another bottle instead of being downcycled or burned. That's not a small thing. Multiply it by billions of items annually across thousands of facilities, and you've got the outline of an industrial transformation as significant as the assembly line revolution a century ago.

The future of recycling isn't just automated. It's intelligent, adaptive, and increasingly effective. The revolution is here, sorting through our waste stream one thousand items per hour at a time.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

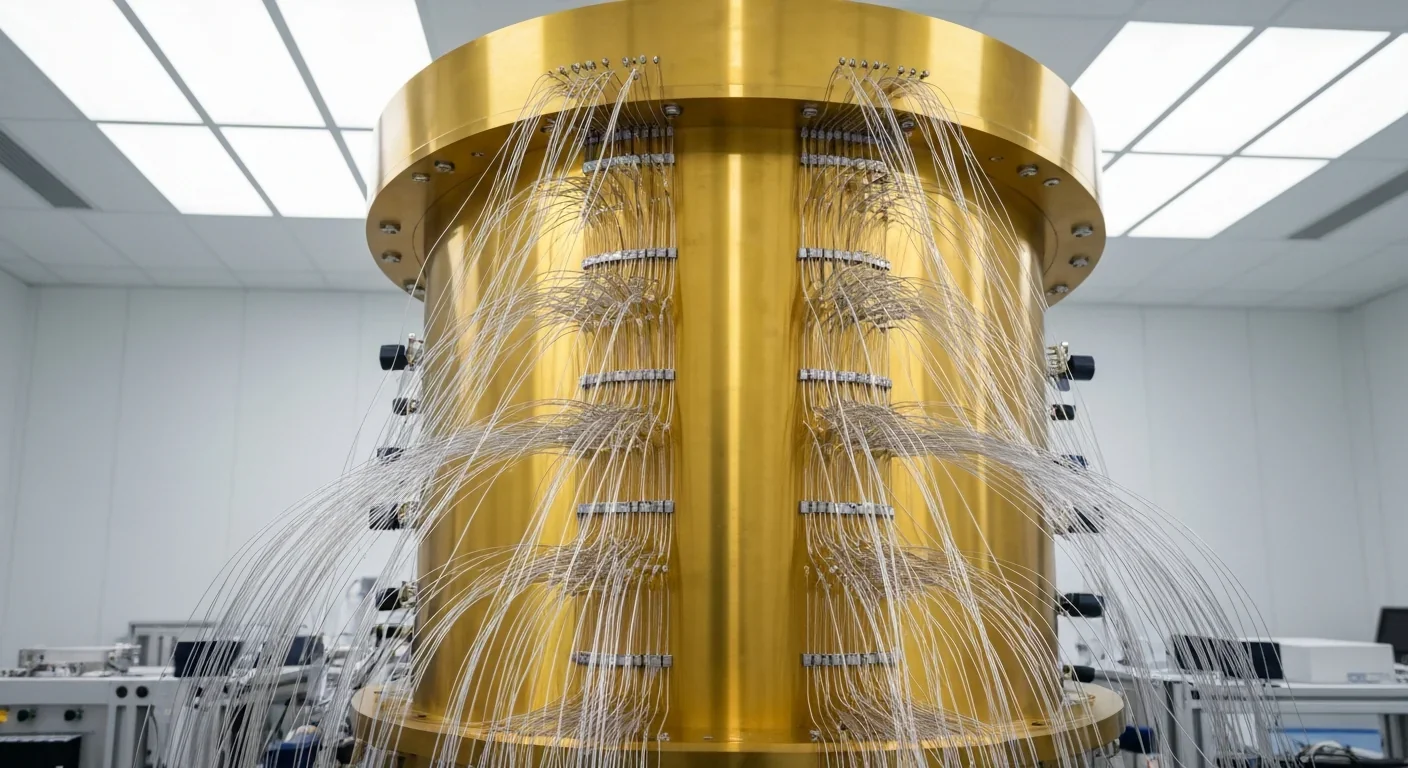

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.