3D-Printed Coral Reefs: Can We Engineer Marine Recovery?

TL;DR: The Amazon rainforest is approaching a critical tipping point where deforestation and climate change could irreversibly transform it into savanna. Scientists warn we have until the 2030s to reverse these trends before the ecosystem collapses.

By the mid-2030s, scientists predict the Amazon could reach a point where it can no longer sustain itself as rainforest. The world's largest tropical forest is inching toward a threshold that would transform it into something entirely different: a savanna-like ecosystem. This isn't science fiction or distant prophecy. Right now, parts of the Amazon have already flipped from absorbing carbon to emitting it, and the feedback loops driving that change are accelerating.

The concept of a tipping point isn't just dramatic language. When you clear enough forest, you disrupt the water cycle so severely that the remaining trees can't generate enough moisture to sustain themselves. The Amazon essentially makes its own rain through a process called moisture recycling. Trees pull water from the soil, release it through their leaves, and that moisture forms clouds that travel across the basin. Some of that water cycles through the forest five or six times before it finally reaches the Andes.

Cut down too many trees, though, and that cycle breaks. Research tracking 35 years of data shows that deforestation has accounted for 74% of the decline in dry season rainfall and about 17% of the temperature increase. The relationship isn't even linear - it follows a logarithmic curve, meaning the first waves of deforestation hit especially hard.

Most scientists point to somewhere between 20% and 25% forest loss as the danger zone. When you cross that threshold, the system can collapse into a self-reinforcing spiral. Less forest means less rain, which stresses the remaining trees, making them more vulnerable to fire and drought, which kills more trees, which reduces rain further.

Amazon forest cover dropped from 89.1% in 1985 to 78.7% in 2020. That's a 10.4 percentage point decline in just 35 years. If current rates continue, deforestation could hit 32.4% by 2035, pushing temperatures up another 2.64°C and slashing dry season rainfall by an additional 28 millimeters.

There's another piece of this puzzle that doesn't get enough attention: the so-called flying rivers. These aren't actual rivers in the sky, but massive streams of moisture that flow westward from the Atlantic across the Amazon basin. At least 75% of rainfall in the Amazon gets recycled this way. The forest acts like a giant atmospheric pump, moving water from one region to another.

Deforestation creates gaps in this moisture highway. When you clear a patch of forest, runoff can jump to 50% - all that water just flows away instead of cycling back into the atmosphere. The western Amazon, which depends heavily on moisture transported from the east, becomes especially vulnerable.

Infrastructure projects amplify the problem. The proposed BR-319 highway would cut through a critical corridor, potentially blocking moisture flow to downstream regions. Matt Finer, director of the Monitoring of the Andes Amazon Project, notes that most public discussion of the tipping point misses this complexity. It's not just about how many trees you cut down - where you cut them matters enormously.

If deforestation is pushing the Amazon toward a cliff, fire is the thing that could shove it over the edge. Brazil recorded more than 42,000 fires between January and August 2024, the highest count in nearly two decades. These weren't natural events. Most resulted from deliberate burning to clear land, made worse by drought conditions.

Fire fundamentally changes the forest. A rainforest isn't supposed to burn - it's too wet. But as deforestation and rising temperatures dry out the understory, flames can spread through areas that would have been fireproof a generation ago. Once fire gets into a tropical forest, it kills trees that took centuries to grow, releases massive amounts of carbon, and leaves the landscape more vulnerable to burning again.

The feedback loop becomes vicious. Drought leads to more fires, which kill more trees, which reduces rainfall, which causes more drought. The system starts consuming itself. Parts of the Amazon that historically absorbed carbon dioxide are now net emitters, largely because of this fire-deforestation-drought cycle.

Scientists warn that surpassing 1.5°C of global warming will trigger increasingly extreme and irreversible events in the Amazon. We're already seeing what that looks like. The 2023 drought was historic - rivers dried up, communities lost access to water, and the 2024 fire season that followed shattered records.

The ecological consequences of crossing the tipping point would ripple far beyond the Amazon basin. The forest currently holds something like 150 billion metric tons of carbon in its trees and soil. Converting that forest to savanna would release much of that carbon into the atmosphere, accelerating global warming in a way that no amount of emissions cuts could quickly counteract.

Biodiversity loss would be staggering. The Amazon hosts roughly 10% of all species on Earth. Many of those species can't survive in savanna conditions. We're not just talking about jaguars and macaws - though we'd lose plenty of those too. The forest contains countless undiscovered species, many of which could hold keys to new medicines or agricultural innovations. Once they're gone, they're gone for good.

The hydrological changes would extend well beyond the forest itself. The Amazon generates atmospheric rivers that carry moisture south to agricultural regions in Brazil, Paraguay, and Argentina. Disrupt that flow and you affect rainfall patterns across a huge swath of South America. Studies suggest the Pantanal wetlands and agricultural zones could see significantly reduced precipitation, threatening food production for hundreds of millions of people.

Indigenous communities, who have stewarded the forest for millennia, would lose their homes and ways of life. About 400 indigenous groups live in the Amazon, speaking more than 300 languages. These communities have proven to be the most effective forest guardians, with deforestation rates in indigenous territories far lower than in unprotected areas. A savanna transition would destroy not just ecosystems but entire cultures.

Here's where the story gets more complicated. Recent research has found that large, old trees in the Amazon are more resilient than scientists expected. These giants are using rising CO2 levels to grow faster, essentially getting fatter as they pull more carbon from the air.

A study tracking thousands of trees found that big trees are actually thriving in some areas, defying earlier predictions of widespread die-off. The increased CO2 acts like fertilizer, allowing mature trees to bulk up their trunks and branches. This offers a sliver of hope - if we stop clearing forests and suppress fires, the trees that remain might have some capacity to adapt.

But this resilience has limits. These trees need water, and if deforestation keeps shrinking the forest and disrupting the hydrological cycle, even the toughest trees will eventually succumb. Research shows that trees rely heavily on recent rainfall during the dry season, meaning they're fundamentally dependent on the moisture recycling system staying intact. You can't CO2-fertilize your way out of a collapsed water cycle.

Understanding why the Amazon is being cleared requires looking at the economic forces at play. Cattle ranching drives the majority of deforestation, followed by soy production and logging. These industries generate short-term profits for landowners and contribute to Brazil's GDP, creating powerful incentives to keep clearing.

Government policies have oscillated wildly based on who's in power. Brazil dramatically reduced deforestation between 2004 and 2012 through a combination of satellite monitoring, law enforcement, and market incentives. Deforestation rates fell by more than 80%. But when political winds shifted and enforcement weakened, clearing surged again.

Infrastructure development poses another challenge. Roads like BR-319 promise to connect remote communities and stimulate economic development. But they also open up vast areas to illegal logging and land speculation. Every new road becomes a deforestation front, with settlers and businesses clearing forest on either side.

The economic calculation is myopic, though. The Amazon generates far more value as a functioning ecosystem than as cleared land. The forest regulates rainfall for agriculture across South America, potentially worth hundreds of billions of dollars. It holds genetic resources of incalculable value. And it stores carbon that, if released, would impose climate damages measured in trillions.

Preventing the Amazon from crossing its tipping point requires action on multiple fronts. First, deforestation needs to not just slow down but stop. Brazil has shown this is possible when there's political will. Satellite monitoring makes it easy to detect illegal clearing in near-real-time. The challenge is enforcement and providing economic alternatives to people who depend on forest clearing for their livelihoods.

Indigenous land rights offer one of the most cost-effective conservation strategies. Areas under indigenous management have deforestation rates five to ten times lower than similar areas without protection. Strengthening indigenous land tenure and supporting traditional management practices could protect huge areas at relatively low cost.

Restoration needs to become a priority, not just an afterthought. Degraded areas can be brought back, but it requires sustained effort and funding. Reforestation projects work best when they involve local communities and use native species. Some regions have shown that recovery is possible, with cleared areas gradually returning to forest when given the chance.

Climate finance could shift the economic equation. Brazil has proposed ambitious plans to fund forest protection through international climate financing. The logic is straightforward: wealthy countries that have already developed while clearing their own forests help pay to keep the Amazon standing, because everyone benefits from the climate stability it provides.

Global cooperation matters too. The Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization brings together the eight countries that share the basin, though coordination has been uneven. When neighboring countries work together on enforcement and monitoring, illegal activities become harder to hide.

Here's the uncomfortable truth: we're running out of time to get this right. The Amazon isn't going to collapse overnight, but the evidence suggests we're close enough to the threshold that the next decade or two will be decisive. Once the system tips into a new state, reversing it would take centuries if it's even possible at all.

The choices we make now about forest protection, climate policy, and development priorities will determine whether our children inherit a functioning Amazon rainforest or a degraded savanna. The science is clear about what's happening and what's at stake. What remains uncertain is whether we'll act on that knowledge before it's too late.

Every year of delay makes the challenge harder. Soil degradation from fires and farming reduces the forest's ability to regenerate. The longer we wait, the more extensive and expensive restoration efforts become. At some point, you pass the point where restoration is even feasible.

But the fact that we're not past that point yet means there's still a path forward. The Amazon has survived ice ages and millennia of climate fluctuations. What it can't survive is unchecked deforestation combined with rapid warming. We built the systems and policies that are driving the forest toward collapse. That means we can also build the systems and policies that pull it back from the edge.

The question isn't whether we can save the Amazon. The question is whether we will.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

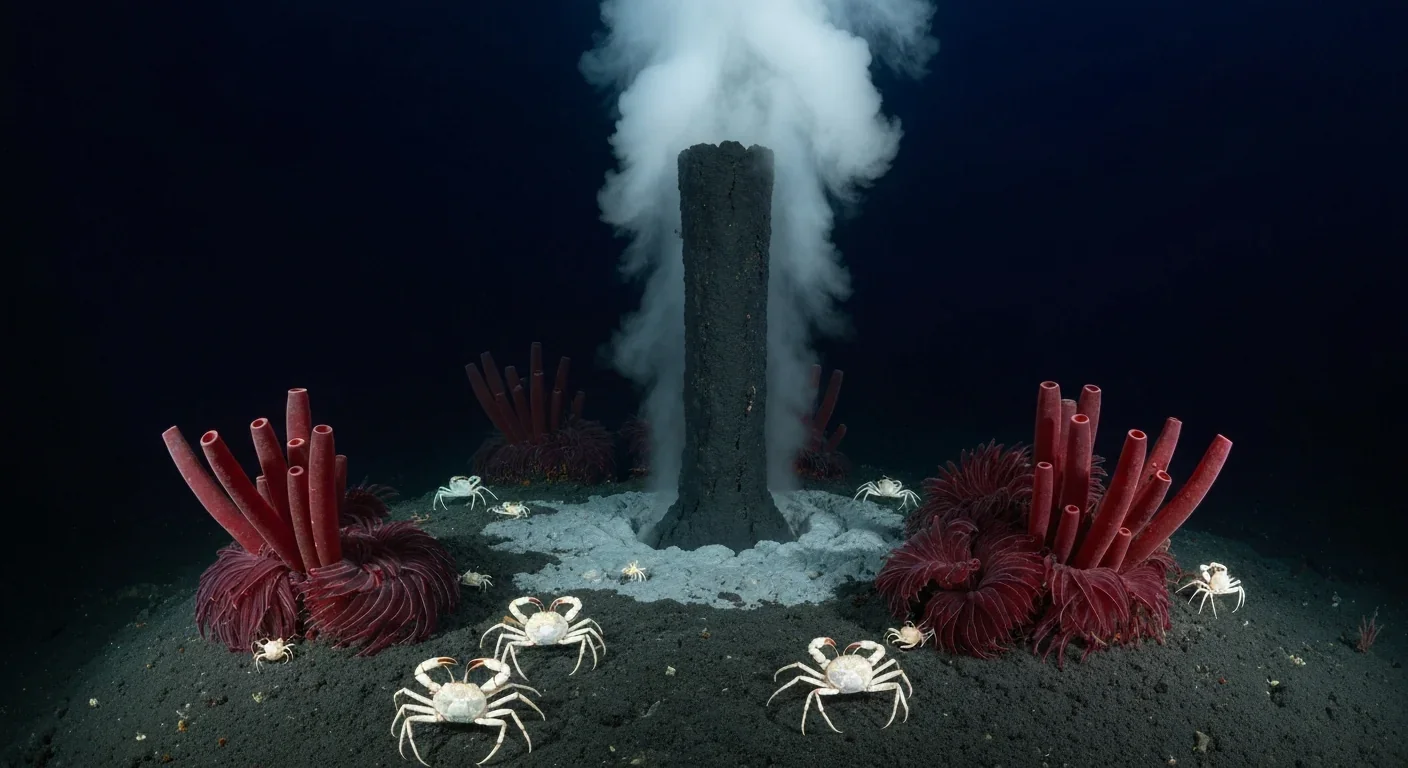

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

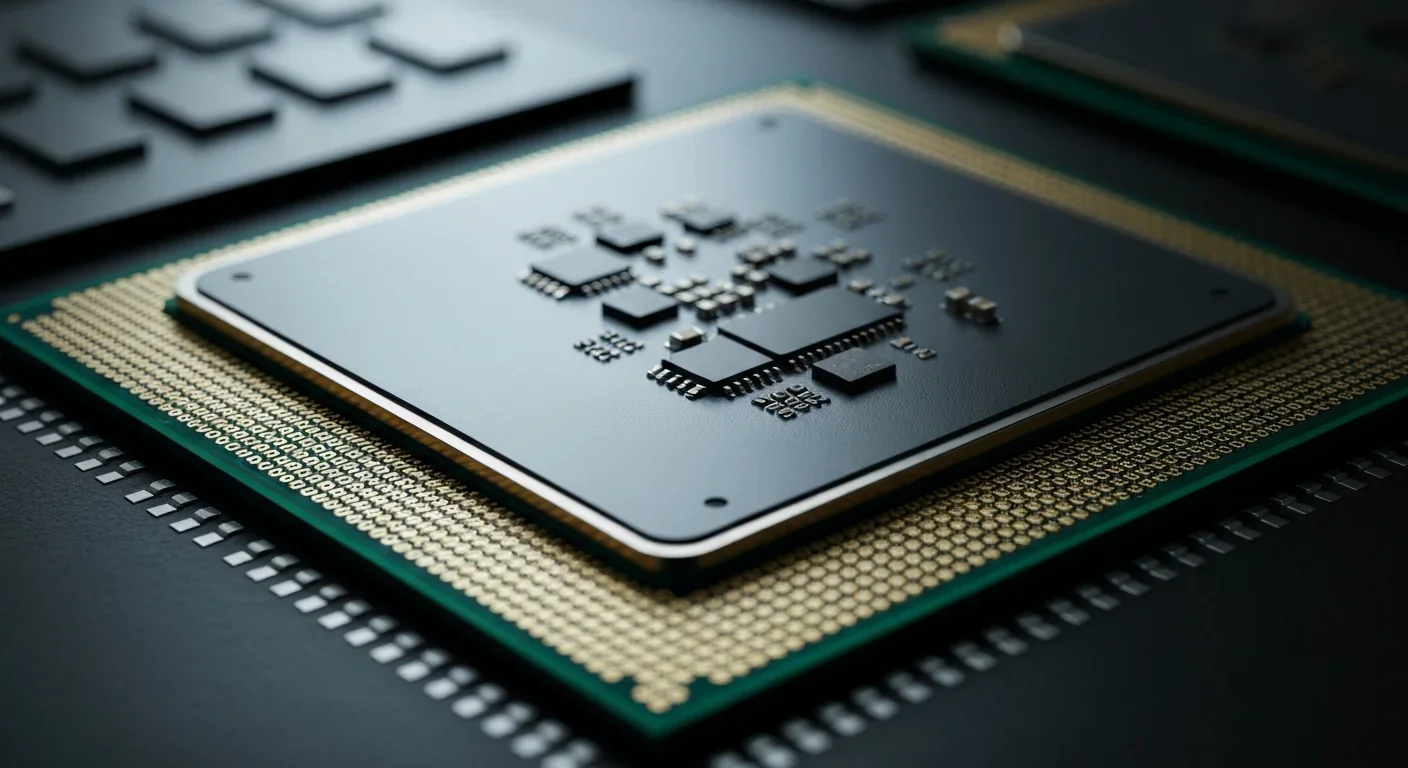

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.