AI Cameras Save Sea Turtles in Fishing Nets

TL;DR: Artificial reefs transform sunken ships, oil platforms, and 3D-printed structures into thriving marine ecosystems. While controversies persist around materials and placement, these engineered habitats accelerate ocean restoration when integrated into comprehensive conservation strategies.

Off the coast of Virginia Beach, something remarkable is happening 100 feet beneath the waves. The USS United States, once the fastest ocean liner ever built, is being transformed into what will become the world's largest artificial reef. Within months of deployment, marine life that took decades to disappear from overfished waters will return en masse. It's a pattern repeating itself worldwide, from decommissioned oil platforms in the Gulf of Mexico to 3D-printed coral structures in the Mediterranean. These aren't just disposal projects disguised as conservation - they represent a fundamental shift in how humanity approaches ocean restoration.

Artificial reefs work because ocean ecosystems are built on hard surfaces. Natural reefs take centuries or millennia to form, but marine life doesn't wait around for geology. Drop a structure with the right characteristics - surface complexity, stable materials, strategic placement - and colonization begins within hours.

The science behind successful artificial reefs centers on understanding what marine organisms need. Research shows that surface texture matters as much as size. Barnacles, algae, and coral polyps need rough surfaces to attach. Small fish need crevices for protection. Larger predators need open water nearby for hunting. It's architectural design for a non-human clientele.

Engineers now use parametric intelligence to optimize reef structures before they hit the water. Smart Enhanced Reefs incorporate sensors that monitor water quality, biodiversity, and structural integrity in real time. These aren't passive structures anymore - they're responsive ecosystems that adapt to changing conditions.

Smart Enhanced Reefs use parametric intelligence to optimize water currents and organic particle retention in real time, creating an engineering-ecology feedback loop that natural reefs took millennia to develop.

The materials matter enormously. Early attempts using tire reefs proved catastrophic. Florida's Osborne Reef, created from two million tires in 1972, became an environmental disaster when hurricanes scattered the tires across natural reefs, smothering coral and creating a toxic cleanup nightmare that continues today.

Modern artificial reefs use purpose-designed concrete with specific pH levels to encourage coral attachment, steel cleaned of contaminants, and increasingly, 3D-printed structures that mimic natural reef complexity with precision impossible through traditional manufacturing.

The transformation of military vessels into marine habitats represents one of conservation's stranger success stories. The EPA's Ships to Reefs program has strict protocols - every piece of PCB-containing material removed, fuel tanks emptied, hatches opened to allow fish passage. What remains becomes prime real estate for marine colonization.

Within weeks of sinking, biofilm forms on surfaces. Within months, barnacles and oysters establish colonies. Within a year, small fish move in. Within five years, the structure supports a biomass density often exceeding nearby natural reefs.

The USS Oriskany, a 911-foot aircraft carrier sunk off Pensacola in 2006, now hosts more than 225 fish species. Its flight deck has become a gathering place for goliath groupers, critically endangered fish that can weigh 800 pounds. The carrier's internal spaces shelter smaller species, creating a vertical ecosystem stratified by light, current, and predator-prey relationships.

But not every vessel makes a suitable reef. Preparation costs can exceed $500,000 per ship. Environmental groups have challenged poorly cleaned vessels, arguing that toxic materials leach into surrounding waters. The debate illustrates a larger tension: whether artificial reefs genuinely restore ecosystems or simply concentrate existing fish populations in convenient locations for commercial fishing.

When oil companies propose converting offshore platforms into reefs, environmentalists split into opposing camps. One side sees ecological opportunity - structures that already host thriving marine communities, converted at a fraction of the cost of full removal. The other sees corporate greenwashing - companies avoiding expensive dismantling obligations by rebranding abandonment as conservation.

"California's 27 offshore platforms support an estimated biomass per unit area 27 times higher than natural reefs nearby. These structures have created vertical habitats in deep water where natural reefs don't exist."

- Scientific American

The data complicates simple narratives. California's 27 offshore platforms support an estimated biomass per unit area 27 times higher than natural reefs nearby. These structures have created vertical habitats in deep water where natural reefs don't exist, allowing species to inhabit zones previously unavailable to them.

Yet critics point to ongoing contamination risks, arguing that industry-funded studies downplay long-term environmental costs. They note that companies save billions in decommissioning expenses through Rigs to Reefs programs, raising questions about whose interests these conversions truly serve.

The regulatory landscape reflects this ambiguity. Some states, like Louisiana and Texas, have embraced platform conversions, using cost savings to fund marine conservation programs. California maintains stricter requirements, insisting that platforms be partially removed even when converted to reefs, ensuring companies bear significant decommissioning costs.

Commercial fishers have understood artificial reef benefits for decades. Studies in the Mediterranean show catch rates near artificial reefs can be three to five times higher than surrounding areas. This concentration effect drives much of the political support for reef programs - fishers want more reefs, recreational divers want more dive sites, and coastal communities want more tourism.

But does concentrating fish populations help or harm overall fishery health? The "attraction versus production" debate has raged for years. Do artificial reefs create new habitat that supports additional fish, or do they simply aggregate existing populations in ways that make overfishing easier?

Recent research suggests the answer is "both." Well-designed reefs in appropriate locations can increase local carrying capacity, supporting larger populations. Poorly placed reefs might concentrate fish without providing adequate food sources, creating ecological traps that make populations more vulnerable.

The economic benefits extend beyond fishing. Florida's artificial reef program generates an estimated economic impact of $5 billion annually through recreational diving and fishing. Coastal communities increasingly view reef deployment as economic development strategy, not just environmental restoration.

This economic dimension complicates conservation goals. When artificial reefs become tourism infrastructure, management priorities shift toward maximizing visitor experience rather than ecological outcomes. The most biologically productive reef designs might not create the best diving experiences, forcing managers to balance competing objectives.

Not every artificial reef succeeds. The Osborne tire reef disaster remains the most spectacular failure, but it's not alone. Concrete structures have crumbled prematurely. Metal has corroded faster than expected. Reefs have been placed in locations with unsuitable currents or sediment conditions, getting buried or swept away.

India's recent artificial reef experiments illustrate both promise and pitfalls. Some structures deployed off Kerala showed rapid colonization and supported increased fish populations. Others failed to attract marine life or suffered structural damage during monsoon seasons, highlighting the importance of local environmental knowledge in design and placement.

The most critical lesson from artificial reef failures: they cannot compensate for broader ecosystem destruction. Deploying reefs while ignoring overfishing, pollution, and climate change is like installing smoke detectors while the house burns.

The failures teach critical lessons. Material selection must account for long-term environmental conditions, not just initial cost. Placement requires detailed understanding of currents, sediment transport, and seasonal variations. Monitoring needs to continue for years, not just the first few months when public attention remains high.

Perhaps most importantly, artificial reefs alone cannot compensate for broader ecosystem destruction. They work best as part of comprehensive conservation strategies that address overfishing, pollution, and climate change. Deploying reefs while ignoring these fundamental threats is like installing smoke detectors while the house burns.

Zaha Hadid Architects' collaboration with marine scientists represents a new approach to reef design. Using computational modeling and 3D printing, they create structures that mimic natural reef complexity at multiple scales - from microscopic surface texture that encourages coral polyp settlement to macro-level forms that create diverse current patterns and habitat zones.

The technology allows rapid iteration. Researchers can test designs virtually, optimize for specific species or locations, and print custom structures at relatively low cost. Clay printing offers particular promise, using locally-sourced materials that integrate with natural sediments and provide ideal pH for coral growth.

Early deployments of 3D-printed reefs in Monaco and the Netherlands show encouraging results. Coral recruitment rates exceed those on traditional concrete structures. Fish diversity increases more rapidly. The ability to embed sensors during printing enables detailed monitoring without retrofitting existing structures.

However, scaling remains challenging. 3D printing works well for research projects and small deployments, but large-scale reef creation still requires more conventional approaches. The technology is evolving rapidly, though - what seems experimental today might become standard practice within a decade.

The integration of Internet of Things sensors into reef structures enables unprecedented understanding of ecosystem dynamics. Temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen, turbidity, acoustic signatures - all monitored continuously and transmitted to researchers.

This data revolution changes how we evaluate reef success. Instead of periodic diver surveys providing snapshots, smart reefs offer continuous observation. Researchers can correlate environmental conditions with biological responses, identifying optimal parameters for different species and life stages.

Hydrophone arrays detect changes in reef soundscapes as ecosystems develop. Healthy reefs are noisy places - snapping shrimp, feeding fish, and vocalizing marine mammals create acoustic signatures that indicate biodiversity levels. Smart reefs can alert managers when acoustic patterns suggest ecosystem stress before visual surveys would detect problems.

The monitoring capabilities also enable adaptive management. If sensors detect declining oxygen levels or water quality issues, managers can intervene quickly. If certain habitat zones attract target species, future designs can emphasize those characteristics. The feedback loop between deployment and design accelerates learning.

Beyond supporting fisheries and biodiversity, artificial reefs provide coastal protection benefits increasingly valuable as climate change accelerates. Well-designed structures can reduce wave energy by 30-70%, protecting shorelines from erosion while creating marine habitat.

Romania's Danube Delta project illustrates this multi-benefit approach. Researchers modeled artificial reef configurations to maximize both coastal protection and ecological function. The optimal designs reduced wave height significantly while creating diverse habitat zones for different species.

"Why build separate coastal protection infrastructure and conservation projects when one structure serves both purposes? The engineering challenges are significant, but the potential cost savings drive innovation."

- Coastal Engineering Researchers

This dual-purpose approach appeals to budget-conscious governments. Why build separate coastal protection infrastructure and conservation projects when one structure serves both purposes? The engineering challenges are significant - structures must withstand storm forces while maintaining the complexity marine life requires - but the potential cost savings drive innovation.

As sea levels rise and storms intensify, coastal communities face difficult choices about protection strategies. Traditional hardening with seawalls and riprap often degrades nearshore ecosystems. Artificial reefs offer a nature-based alternative that works with ecological processes rather than against them.

While artificial reefs create new habitat, they also serve as platforms for active coral restoration. Researchers grow coral fragments in nurseries, then transplant them to artificial structures designed to optimize survival. The combination of habitat creation and species reintroduction accelerates recovery.

The design of reef structures significantly influences restoration success. Surface geometry affects how water flows across surfaces, which determines nutrient delivery to coral polyps and waste removal. Orientation affects light exposure, temperature variation, and sedimentation. Getting these details right can double or triple coral survival rates.

Some restoration projects use drone technology to map reef structures, monitor coral growth, and guide management decisions. The combination of artificial substrate, coral cultivation, and advanced monitoring creates restoration approaches impossible even a decade ago.

But coral restoration faces fundamental challenges that technology alone cannot solve. Rising ocean temperatures from climate change threaten corals globally. Ocean acidification reduces the ability of corals to build skeletons. Without addressing these root causes, even successful local restoration might prove temporary.

Deploying artificial reefs requires navigating complex regulatory frameworks. In the United States, the EPA requires permits under the Marine Protection, Research, and Sanctuaries Act. States maintain additional requirements through coastal zone management programs. The approval process can take years and requires extensive environmental assessment.

International guidelines emphasize precautionary approaches. The London Convention regulates ocean dumping, including artificial reef deployment. Countries must ensure materials are environmentally safe, placement doesn't harm existing ecosystems, and monitoring continues long-term.

Successful artificial reef programs share key characteristics: thorough site assessments, purpose-built materials over waste disposal, long-term monitoring, and deep community engagement with fishers, divers, and coastal residents.

Best practices have emerged from decades of trial and error. Successful programs conduct thorough site assessments before deployment, selecting locations with appropriate depth, current, and sediment conditions. They prioritize purpose-built materials over waste disposal convenience. They implement long-term monitoring and adaptive management.

Community engagement matters enormously. Projects developed with input from fishers, divers, environmental groups, and coastal residents navigate regulatory processes more smoothly and achieve better outcomes. Local knowledge often identifies potential problems that desktop studies miss.

As ocean temperatures rise and acidification intensifies, artificial reefs face new challenges. Materials must withstand more intense storms. Designs must account for changing species ranges as tropical species move poleward. What worked in historical ocean conditions might fail in the rapidly changing environments ahead.

Some researchers focus on creating climate-resilient reefs - structures designed to support species and ecological functions even under future conditions. This requires understanding not just current ecosystems but projected changes over 50-100 year timescales.

Others question whether artificial reefs distract from more fundamental action on climate change. If rising temperatures make tropical waters uninhabitable for coral, deploying artificial reef structures in those locations might waste resources better spent on emissions reduction.

The debate reflects broader tensions in conservation biology. How much should we intervene to preserve species and ecosystems threatened by human-caused change? When does active management become futile resistance to inevitable transformation?

Artificial reefs work best when integrated into comprehensive ocean management. They cannot replace natural reefs, compensate for overfishing, or reverse climate change. But deployed thoughtfully, they accelerate ecosystem recovery, support biodiversity, and provide economic benefits to coastal communities.

The technology and understanding continue advancing rapidly. Startups developing new materials and designs attract investment from conservation organizations and venture capital alike. Governments increasingly view reef deployment as climate adaptation strategy. The field is maturing from experimental phase to established practice.

Yet success requires learning from failures. The tire reefs and poorly cleaned vessels remind us that good intentions don't guarantee positive outcomes. Rigorous science, careful planning, long-term commitment, and honest assessment of what artificial reefs can and cannot accomplish - these determine whether projects restore ecosystems or create new problems.

As the USS United States settles to the ocean floor, it joins hundreds of structures worldwide in a vast unintentional experiment. We're learning to build underwater cities designed for non-human inhabitants, engineering ecosystems rather than simply protecting what remains. Whether this represents hubris or hope depends on the choices we make about design, deployment, and the broader systems these structures inhabit.

The ocean is still declining globally - overfished, polluted, warming. Artificial reefs are band-aids on wounds requiring surgery. But they're remarkably effective band-aids, and in conservation, we take victories where we can find them. Each successful reef project demonstrates that human engineering can sometimes support rather than destroy natural systems. That lesson, applied more broadly, might matter more than any individual structure we sink beneath the waves.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

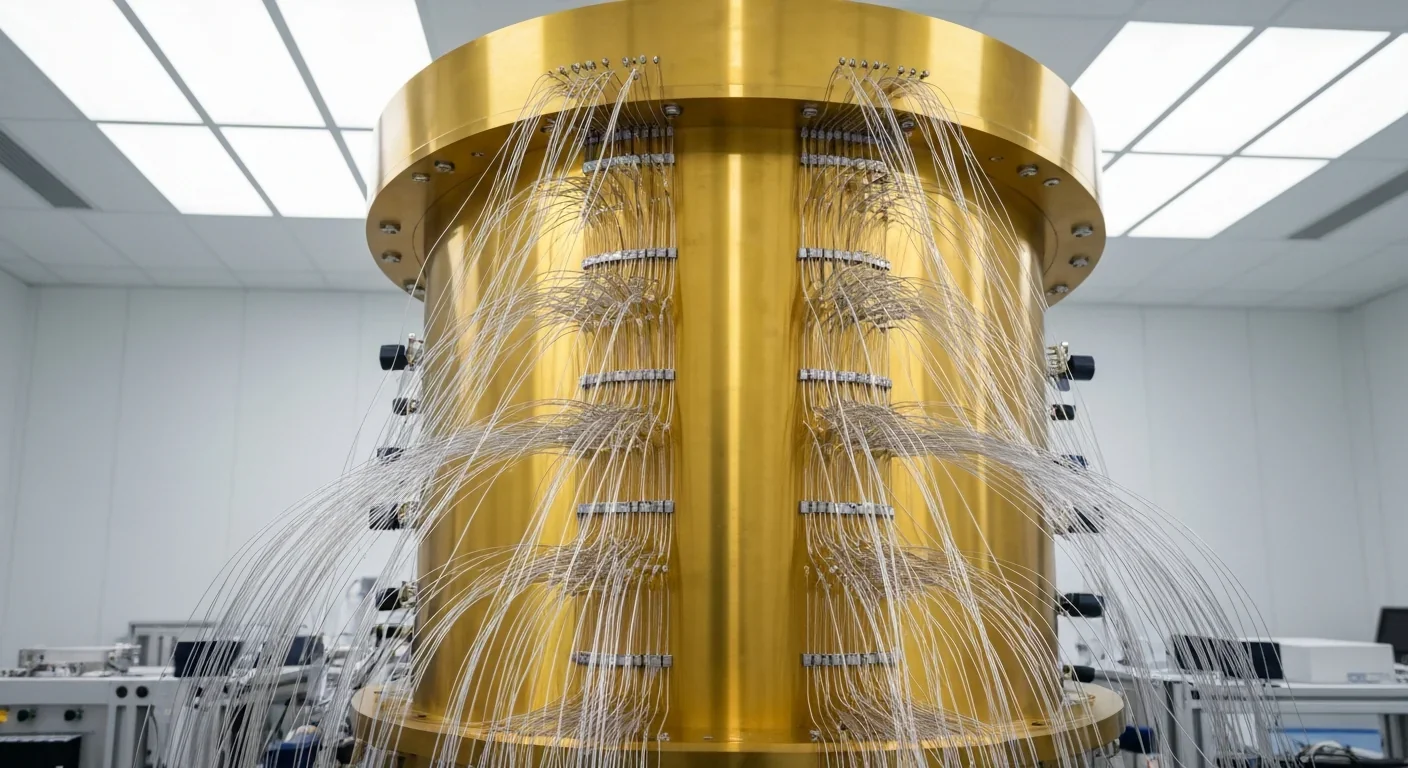

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.