3D-Printed Coral Reefs: Can We Engineer Marine Recovery?

TL;DR: Scientists are relocating endangered species to new habitats as climate change makes their native homes uninhabitable. While some projects like the Florida torreya relocation show promise, critics warn this controversial strategy could create invasive species and ecological disasters worse than extinction itself.

Imagine waking up to discover your home is no longer livable. The temperature has risen 5 degrees, water sources have dried up, and the ecosystem you depend on has collapsed. You'd move, right? But what if you're a tree, rooted to one spot, or a butterfly whose wings can only carry you a few miles? That's the predicament facing millions of species as climate change transforms their habitats faster than they can adapt. Some scientists believe we need to help these species relocate before it's too late. Others warn that moving species could trigger ecological catastrophes worse than extinction itself.

For generations, conservation meant one thing: protect species where they live. Build reserves, eliminate threats, restore habitats. But climate change has rewritten the rulebook. Species are losing their homes not to bulldozers or poachers, but to shifting temperature zones and altered rainfall patterns that render their native ranges uninhabitable.

Enter assisted migration, also called assisted colonization or managed relocation. The concept is deceptively simple: if a species can't reach suitable habitat on its own, we move it there. Scientists identify locations with the right climate conditions, transport individuals, and hope they establish thriving populations. It's conservation meets climate adaptation, with humans actively reshaping where species live to match where they can survive.

The urgency is real. Climate zones are shifting poleward at roughly 17 kilometers per decade. Plants and animals are trying to keep pace, but many can't move fast enough. Mountain species are running out of altitude as temperatures rise. Coastal ecosystems face drowning from sea level rise. Species with limited dispersal ability, like many plants and insects, simply can't cross the landscapes humans have fragmented with cities, farms, and highways.

The Florida torreya tells one of assisted migration's most compelling success stories. This ancient conifer once thrived in the ravines of northern Florida and southern Georgia, but by the 1950s, a fungal disease and changing climate had decimated populations. Fewer than 1,000 individuals remained, none reproducing successfully in the wild.

In 2008, a citizen group called Torreya Guardians began relocating seedlings 600 kilometers north to the mountains of North Carolina. Critics called it reckless. Regulators worried about creating an invasive species. But by 2018, documentation showed the relocated trees weren't just surviving but thriving. They were producing viable seeds and next-generation saplings, something they hadn't done in their native range for decades.

The bay checkerspot butterfly offers another validation. Researchers studying this California species used climate modeling to identify sites that would become suitable habitat as temperatures warmed. When they introduced butterflies to these predicted zones, the populations established successfully, matching the model's projections. The experiment demonstrated that science could reliably identify where species would thrive in a warmer future.

Forest managers in North America are conducting perhaps the largest assisted migration experiments. They're planting tree seedlings from populations hundreds of kilometers south of traditional planting sites, anticipating that today's southern climate will be tomorrow's northern climate. The approach aims to maintain productive forests as climate zones shift faster than trees can migrate naturally.

Every conservation biologist knows the horror stories. Cane toads released in Australia to control beetles instead became an ecological disaster, poisoning native predators across the continent. Kudzu vine, introduced to control erosion in the American South, now smothers millions of acres. These cautionary tales fuel the primary objection to assisted migration: today's climate refugee could become tomorrow's invasive monster.

The fear isn't hypothetical. A species that behaves benignly in its native ecosystem, constrained by predators, competitors, and diseases, might become dangerously aggressive when relocated. Without these natural checks, a transplanted species could outcompete native organisms, alter food webs, or transform entire ecosystems in unforeseen ways.

Yet the data suggests the risk may be lower than instinct suggests. A review of 468 documented species invasions found that only 14.7% occurred on the same continent where the species originated. Most successful invasions involved long-distance jumps between continents or islands, not the relatively short relocations typical of assisted migration projects. When species move within their continent, they encounter ecosystems that already share many characteristics with their home range.

Still, "lower risk" isn't zero risk. Scientists worry particularly about relocating species to islands or isolated ecosystems with many endemic species. A single aggressive newcomer could devastate communities that evolved in isolation. The consequences of getting it wrong could be irreversible.

The ethical debate around assisted migration cuts deep. Critics frame it as dangerous hubris, humans arrogantly rearranging nature without understanding the consequences. One scientist called it "the ultimate meddling," a Promethean overreach that treats ecosystems as Lego sets we can reconfigure at will.

The counterargument is equally powerful: we've already transformed the planet's climate and fragmented its landscapes. Doing nothing condemns species to extinction when we could save them. From this perspective, assisted migration isn't hubris but moral obligation, a form of planetary hospice care for species our actions have endangered.

The debate also touches on profound questions about what we're trying to preserve. Is the goal to maintain species in their "natural" ranges, even as those ranges become death traps? Or is it to ensure species survive somewhere, anywhere, even if that means fundamentally reshaping where they live? When Yellowstone's climate no longer supports lodgepole pine forests, should we let them die or plant different tree species adapted to the new conditions?

Some conservationists argue we should accept that ecosystems are dynamic, not static museums. If climate change is creating novel ecosystems with no historical precedent, perhaps assisted migration is simply accelerating inevitable changes. Others counter that this thinking abandons the preservation ethic that has guided conservation for over a century.

Not every endangered species is a candidate for assisted migration. Scientists have developed rigorous criteria to distinguish appropriate candidates from risky ones. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) released updated guidelines in 2025 that provide a structured decision-making framework.

Priority candidates typically share several characteristics. They face imminent extinction in their current range due to climate change. They have limited ability to disperse naturally across human-modified landscapes. They show high specificity for particular climate conditions rather than being generalists. They have low invasive potential based on their behavior in similar ecosystems.

The assessment process resembles clinical triage. Scientists model the species' current climate niche, project where suitable conditions will exist in coming decades, and identify potential relocation sites. They evaluate whether the target ecosystem can support the species without negative impacts on resident organisms. They consider whether climate projections are certain enough to justify the intervention.

Feasibility matters too. Some species require such specialized conditions or complex ecological relationships that relocation is effectively impossible. Others, like many plants and some insects, are relatively easy to move and establish. Cost-benefit analysis weighs heavily in a world of limited conservation resources.

The framework also addresses an uncomfortable reality: not everything can be saved. When assisted migration resources are finite, which species deserve priority? Ecologically important species that support entire food webs? Charismatic species that inspire public support? Evolutionarily distinct species representing millions of years of unique adaptation? These triage decisions carry moral weight.

The regulatory landscape for assisted migration is a labyrinth. In the United States, the Endangered Species Act was written to protect species in their native ranges, not to facilitate moving them elsewhere. Relocating an endangered species to a new state might technically violate laws designed to prevent species introductions.

International borders add another layer of complexity. If the ideal climate refuge for a Canadian species lies in Montana, moving it requires navigating two countries' environmental regulations, property rights, and potentially conflicting conservation philosophies. The problem intensifies for species whose future range crosses multiple national boundaries.

Property rights create practical barriers too. Private landowners might understandably object to scientists introducing new species onto their land, especially if those species could potentially become agricultural pests or reduce property values. Securing sufficient protected habitat in predicted future climate zones often proves impossible.

Insurance and liability questions loom large. If an assisted migration project inadvertently creates an invasive species that damages agriculture or natural ecosystems, who bears responsibility? Should government agencies or research institutions that conduct translocations carry liability insurance? The lack of clear legal frameworks makes many institutions reluctant to proceed with projects even when the science supports them.

Some regions are developing specific assisted migration policies. Canadian provinces have begun incorporating climate-adapted seed transfer into forestry guidelines, allowing tree seeds from warmer regions to be planted in anticipation of climate change. Australia has conducted trials for threatened species like the mountain pygmy possum. But globally, policy lags far behind the pace of climate change.

Despite regulatory challenges, assisted migration projects are underway worldwide. The scope ranges from modest experiments to ambitious ecosystem transformations that could redefine conservation practice.

In California, researchers are exploring assisted migration for the Quino checkerspot butterfly, which has disappeared from much of its historic range around Los Angeles and Orange County. Climate models suggest suitable habitat is shifting northward and to higher elevations. Test introductions to predicted suitable sites could provide a refuge population before the species vanishes entirely from the region.

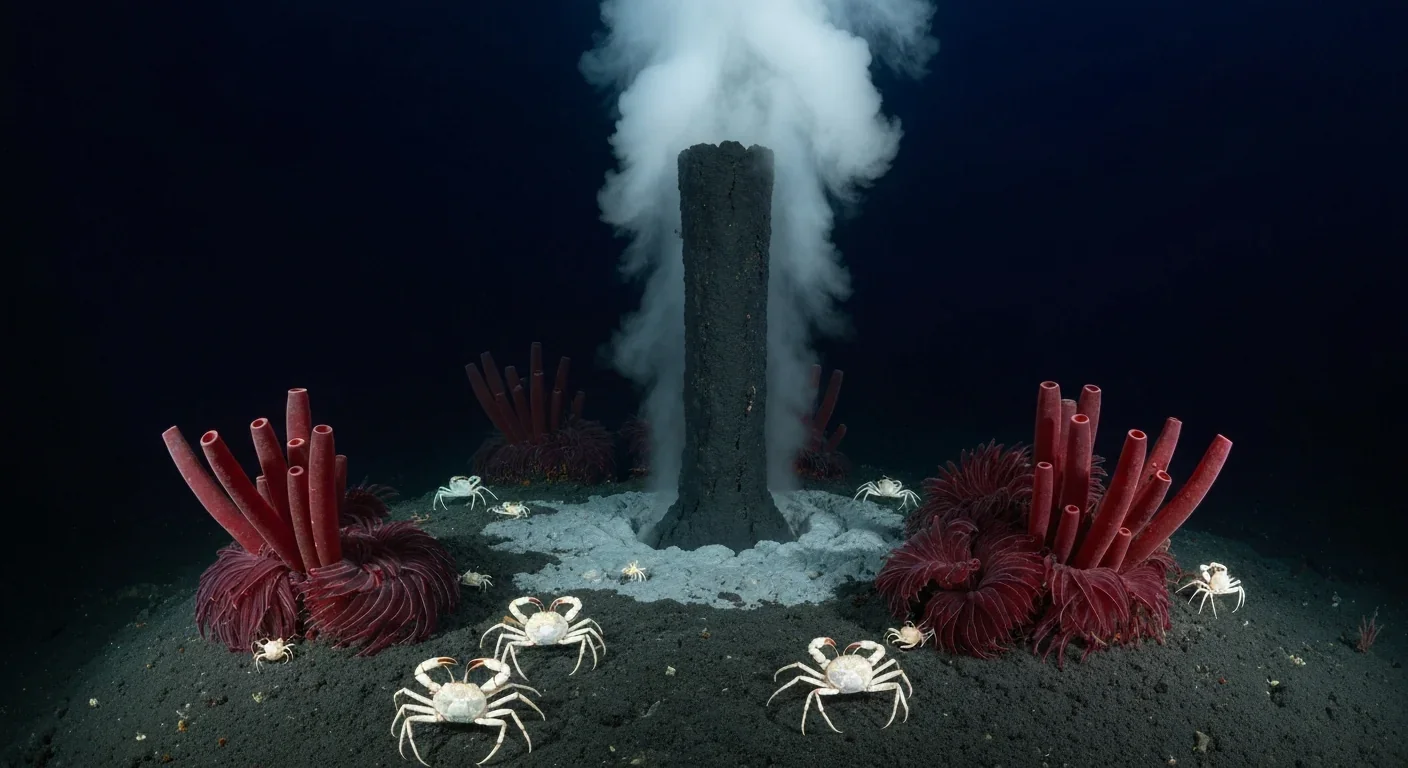

Coral reef scientists are pioneering assisted migration in marine ecosystems. As ocean temperatures rise, corals from warmer regions that have already adapted to higher temperatures are being relocated to cooler reefs likely to warm in coming decades. The approach aims to seed heat-tolerant genetics into vulnerable populations before mass bleaching events make restoration impossible. Fiji has incorporated this strategy into a national coral climate adaptation plan.

The Quiver Tree Project in South Africa takes a different approach. Rather than moving endangered species, it's creating "migration corridors" of protected land that connect current habitats to projected future suitable areas. The hope is that species can naturally disperse along these corridors as climate zones shift, reducing the need for direct human intervention while still facilitating climate-driven range shifts.

Some projects focus on ecosystem function rather than individual species. Functional assisted migration involves moving species specifically to maintain ecosystem services like pollination, seed dispersal, or nutrient cycling as native species decline. If warming kills off important pollinators in a region, introducing pollinator species from warmer areas might preserve the ecosystem's productivity even if the specific species composition changes.

Nature has been conducting assisted migration experiments for millennia, though we called it something else: agriculture, horticulture, and accidental introductions. These historical precedents offer both encouraging successes and sobering warnings.

Humans have successfully relocated thousands of crop species far outside their native ranges. Potatoes from South America now thrive in Idaho. Wheat from the Middle East feeds North America. Rice varieties from Asia grow in California's Central Valley. These relocations succeeded because humans carefully managed the recipient ecosystems, controlled competitors, and provided favorable conditions.

But agricultural successes may offer false confidence. Crop species are typically domesticated generalists selected for adaptability, not specialized wild species with narrow ecological requirements. The careful management that makes agriculture work would be impossible across thousands of square kilometers of wild habitat.

The history of conservation translocations provides more relevant lessons. Species reintroductions to their historic ranges have about a 50% success rate under ideal conditions. Assisted migration faces additional challenges because the recipient ecosystem is outside the species' known range, meaning we're guessing about whether conditions will truly be suitable.

Some relocated species have surprised scientists by thriving in unexpected ways. The American pika, a small mountain mammal, was predicted to suffer dramatically from warming temperatures. Instead, recent research shows pikas are adapting remarkably well, occupying warmer sites than models suggested possible. The findings remind us that species sometimes have hidden resilience we fail to predict.

Conservation operates with brutally limited resources. The money spent relocating one charismatic species could fund habitat protection for dozens of less glamorous organisms. This reality forces uncomfortable calculations about assisted migration's opportunity costs.

Translocation expenses vary wildly by species. Moving a few hundred butterfly larvae to a new hillside might cost tens of thousands of dollars. Relocating large mammals or establishing new populations of long-lived trees could run into millions. Monitoring and adaptive management over decades adds ongoing costs that many projects fail to budget adequately.

The alternative of doing nothing also carries costs, though they're harder to quantify. When a species goes extinct, we lose not just that organism but its ecological relationships, potential future benefits, and a thread in the web of life that took millions of years to evolve. How do we value what extinction erases?

Some economists argue that assisted migration could prove more cost-effective than traditional conservation approaches in a rapidly changing climate. Instead of fighting to maintain species in increasingly unsuitable habitats through ever-more-expensive interventions, relocation accepts that ranges must shift and works with that reality rather than against it.

But this calculus only works if relocations succeed more often than they fail. Every failed project not only wastes resources but potentially creates new problems requiring additional spending to remedy. The financial risk of getting it wrong could undermine broader conservation efforts.

Assisted migration isn't the only tool for helping species adapt to climate change. Conservation strategies exist along a spectrum from passive to active intervention, each with different risk-benefit profiles.

Habitat corridors offer a less interventionist approach. By protecting and restoring connected landscapes, we enable species to shift their ranges naturally as climate changes. This strategy avoids the risks of assisted migration while still facilitating climate adaptation. However, it only works for species capable of dispersing on their own and requires protecting vast landscapes that may not be feasible in densely populated regions.

Ex situ conservation, preserving species in zoos, botanical gardens, and seed banks, provides an insurance policy. If wild populations collapse, captive populations can potentially be reintroduced later. But maintaining species outside their ecosystems for decades is expensive and doesn't preserve the ecological relationships that make species meaningful parts of functioning ecosystems.

Evolutionary rescue through selective breeding or genetic modification represents the most interventionist approach. Scientists could potentially enhance species' heat tolerance, drought resistance, or other climate-relevant traits. This strategy raises even more profound ethical questions than assisted migration, amending the genetic makeup of wild species to match our altered planet.

Some researchers advocate for "rewilding" approaches that focus on restoring ecosystem processes rather than preserving specific species assemblages. This philosophy accepts that ecosystems will transform under climate change and aims to maintain their functionality even if the species composition changes dramatically.

Each approach has ardent advocates and critics. The reality is that comprehensive climate adaptation for biodiversity will likely require all these strategies applied strategically based on specific circumstances rather than one-size-fits-all solutions.

Assisted migration stands at an inflection point. The next ten years will likely determine whether it becomes a mainstream conservation tool or remains a controversial last resort rarely employed.

Climate impacts are accelerating faster than many models predicted. Range shifts, phenology changes, and population declines are happening in real-time across ecosystems worldwide. This urgency is pushing conservationists to move beyond endless debate toward practical experimentation.

Scientific tools for evaluating assisted migration candidates are rapidly improving. Climate models are becoming more precise at predicting local-scale habitat changes. Genomic techniques can assess species' adaptive potential and identify populations with genes suited for future conditions. Risk assessment frameworks are becoming more sophisticated at evaluating invasive potential.

Public attitudes may be shifting too. As climate change impacts become more visible and species extinctions more frequent, tolerance for bold interventions could grow. The generation coming of age now has never known a stable climate and may view actively managing species ranges as necessary rather than hubristic.

Legal and regulatory frameworks are slowly catching up. More jurisdictions are developing specific policies for climate-adaptive conservation, creating pathways for assisted migration projects that previously existed in legal limbo. International bodies are developing guidelines to coordinate cross-border efforts.

The first generation of assisted migration projects is producing results that will inform future decisions. We're learning which species relocate successfully, which ecosystems prove resilient to newcomers, and what factors predict success or failure. This evidence base will allow more informed risk assessment and better targeting of resources.

But challenges remain formidable. Political opposition to environmental regulation is growing in some regions. Funding for conservation continues to shrink relative to the scale of biodiversity crisis. Climate change itself is accelerating, narrowing the window for effective intervention.

Here's what almost no one wants to acknowledge: we're already conducting assisted migration, just accidentally and chaotically. Every time a ship's ballast water introduces marine species to a new port, every time nursery plants carry hitchhiking insects across continents, every time warming allows southern species to survive northern winters, we're reshaping where species live.

The question isn't whether species will move under climate change. They will, either dying out, shifting on their own, or being inadvertently relocated through human activity. The question is whether we'll guide some of these movements strategically based on science and ethics, or whether we'll let chance determine which species survive and where.

Choosing to never attempt assisted migration is itself a choice with profound consequences. It means accepting that many species lacking natural dispersal ability will go extinct even though suitable habitat exists elsewhere. It means watching ecosystems unravel when keystone species disappear, potentially triggering cascading extinctions. It means future generations inheriting a biologically impoverished planet because we were too cautious to act when action might have mattered.

But choosing to embrace assisted migration also carries weight. It means accepting responsibility for outcomes we can't fully predict. It means risking unintended consequences that could harm the ecosystems we're trying to protect. It means fundamentally altering our relationship with nature from preserving what exists to actively managing what will be.

Neither choice is comfortable. Both involve profound ethical and practical challenges. But increasingly, the luxury of avoiding the choice is disappearing. Climate change is forcing our hand, demanding that we decide what we're willing to do to preserve the living world through the transformations ahead.

The species we move, the species we leave, and the species we lose will shape the ecosystems that define our planet for centuries to come. In that sense, we're all conservation biologists now, whether we wanted the job or not. The only question is whether we'll approach it thoughtfully or stumble through it blindly.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

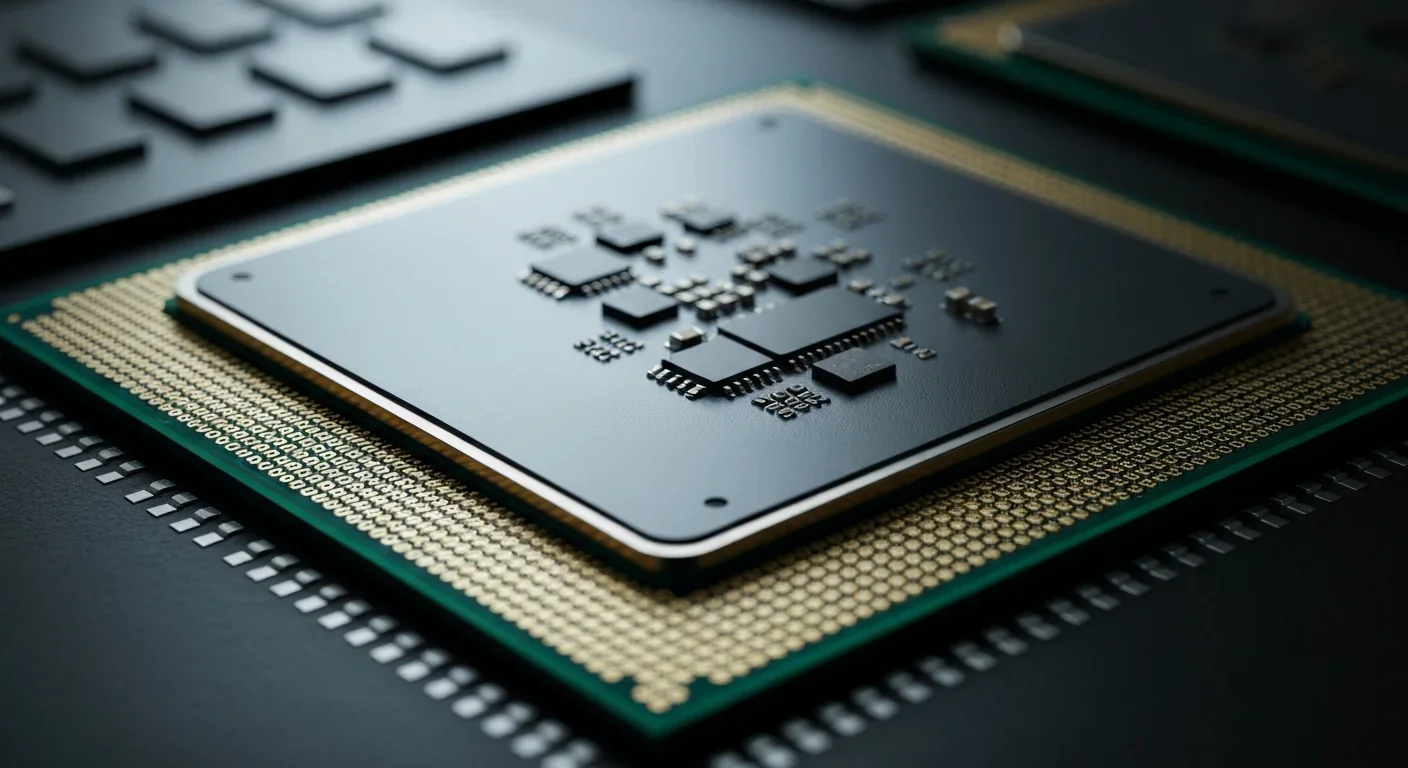

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.