3D-Printed Coral Reefs: Can We Engineer Marine Recovery?

TL;DR: Biological soil crusts are living communities of microorganisms that cover 11% of Earth's land and prevent desertification by reducing evaporation by 75%, stabilizing soil, and fixing atmospheric nitrogen in drylands worldwide.

Picture the desert as a battlefield where life fights an endless war against erosion. While most of us see empty sand and rock, there's an invisible army working beneath our feet. Biological soil crusts, or BSCs, those blackish, crusty patches you've probably stepped over without a second thought, cover about 11% of the planet's land surface and perform a quiet miracle: they stop deserts from consuming the world.

Biological soil crusts aren't just dirt. They're complex communities of cyanobacteria, lichens, mosses, fungi, and algae that weave together into a living carpet just millimeters to centimeters thick. The real architect here is Microcoleus vaginatus, a cyanobacterium that spins filamentous networks through soil particles like microscopic rebar in concrete.

These organisms don't just sit there looking bumpy. Laboratory studies show BSCs reduce evaporation by about 75% compared to bare soil. They create a 30-centimeter water accumulation zone beneath the surface and drop the soil's hydraulic conductivity by three orders of magnitude. Translation? Water that would've vanished into thin air instead gets locked underground where plant roots can reach it.

In China's Loess Plateau, field monitoring over 23 days during the rainy season revealed something striking: BSCs stabilized the evaporation front at 45 to 50 centimeters depth, while bare soil saw that front recede upward from 70 to 40 centimeters. During droughts, surface moisture variation dropped by 40% under BSC cover. During extreme rainfall, they prevented deep soil from becoming waterlogged, keeping moisture peaks at 48.3% instead of the 62.5% seen in bare ground.

What you're looking at is ecohydrological engineering. BSCs don't passively protect soil. They actively reshape how water moves through landscapes.

BSC formation begins with pioneer cyanobacteria colonizing disturbed or bare soil. These early settlers produce extracellular polysaccharides, or EPS, sticky substances that glue sand grains together and create a foundation for more complex life. Over time, lichens arrive, followed by mosses in wetter or cooler areas.

The whole succession can take years or even decades depending on climate and soil texture. Fine-textured, moist soils in temperate zones may recover crust cover in about two years after disturbance. Coarse, dry desert soils? More than 3,800 years in extreme cases. A single footprint can erase centuries of growth.

Once established, these crusts perform functions that dwarf their humble appearance. They contribute at least 15% to terrestrial net primary productivity and account for 40 to 85% of biological nitrogen fixation in drylands. Nitrogen fixation rates range from 0.7 to 100 kilograms per hectare per year, with global estimates around 27 to 99 teragrams annually.

Cyanobacteria dominate in hot, arid deserts like the Sahara and Australian outback. Lichens thrive in temperate and Mediterranean climates. Mosses take over in mid-to-high latitudes and polar regions, where moisture from fog, dew, and snowmelt sustains them even when rainfall is scarce.

The Namib Desert offers a striking example: high lichen cover persists in areas with almost no rain because fog rolls in from the Atlantic, condensing moisture that keeps the crust alive. This micro-climatic dependence means BSCs can flourish in surprising places, defying simple rainfall maps.

Remote sensing and dynamic vegetation models like LiBry have begun mapping global BSC distribution at 0.5-degree resolution, but gaps remain. Hyperspectral imaging, machine learning, and ground-truthing are converging to produce finer-scale maps that could guide restoration efforts with unprecedented precision.

Stabilization tops the list. Filamentous cyanobacteria and fungal hyphae bind soil particles, boosting aggregate stability and slashing erosion rates. In regions prone to wind and water erosion, this binding effect is the difference between stable ground and a dust storm.

Water infiltration improves under BSC cover, but the relationship is nuanced. Early-stage crusts can sometimes reduce infiltration by sealing pores, but mature, well-developed crusts with mosses and lichens often enhance it, channeling water deeper while reducing surface runoff.

Nutrient cycling gets a turbo boost. Cyanobacteria and cyanolichens fix atmospheric nitrogen, turning inert gas into bioavailable nutrients. They also release organic carbon into the soil, feeding microbial communities and supporting the sparse vascular plants that define dryland biodiversity.

BSCs even moderate soil temperature and pH, creating microhabitats for seeds and seedlings. Some plant species depend on BSCs for germination cues and early-stage protection from desiccation.

Livestock grazing ranks as one of the most devastating disturbances. In Patagonian rangelands, light grazing caused an 85% loss of BSC cover. Medium grazing pushed it to 89%. Heavy grazing obliterated 98%. Hooves compress the crust, livestock tear up the filamentous networks, and repeated trampling prevents recovery.

Off-road vehicles, hiking, mining, and military exercises inflict similar damage. A single tire track or boot print can destroy BSC that took decades to form. Recovery time ranges from 50 to 250 years in the American Southwest, depending on moisture and temperature.

Mining activity not only crushes crusts physically but also impairs cyanobacterial photosynthetic potential, delaying biological recovery even after the machinery leaves.

Climate change introduces a double threat. Rising temperatures and shifting precipitation patterns alter the delicate moisture balance BSCs depend on. Drought impacts BSCs more severely than increased rainfall helps them, according to research in Spain's Tabernas Desert. Prolonged dry spells reduce metabolic activity, shrink cover, and shift species composition toward more stress-tolerant but less functionally diverse assemblages.

China's Loess Plateau provides one of the most dramatic examples of large-scale ecological restoration. After decades of overgrazing and cultivation turned the region into an eroded wasteland, authorities implemented grazing bans, terracing, and vegetation planting. BSCs returned naturally as human pressure eased, stabilizing slopes and reducing sediment loads in the Yellow River.

In the American Southwest, land managers use protective fencing, trail design, and public education to shield cryptobiotic soil from recreational damage. Signs reading "Don't Bust the Crust" remind hikers to stay on designated paths. Some agencies close sensitive areas during recovery periods.

Active restoration techniques are emerging. Coarse litter application, vascular plant establishment, and direct inoculation with native cyanobacteria and lichens have shown promise in small-scale trials. Removing stressors like grazing and vehicle traffic remains the easiest and most effective intervention.

Australia's outback has seen experimental BSC inoculation projects where researchers cultivate cyanobacteria in nurseries, then spray them onto degraded soils. Early results suggest colonization accelerates, though long-term success depends on follow-up protection from disturbance.

In the Sahel, community-led initiatives combine BSC protection with agroforestry and rotational grazing. Local knowledge about seasonal migration routes and traditional land use helps identify areas where BSCs can recover without conflicting with livelihoods.

Effective BSC conservation requires integration into land-use planning at multiple scales. National policies should recognize BSCs as critical infrastructure for dryland ecosystems, not just interesting biology. Zoning regulations can designate BSC-rich areas as protected zones where grazing, mining, and recreational access are restricted or managed.

At the farm and ranch level, rotational grazing systems that allow long rest periods, strategic water point placement to reduce trampling hotspots, and livestock density limits can reduce BSC damage. Research shows even moderate grazing intensity causes severe losses, so thresholds must be conservative.

For mining and energy development, pre-disturbance surveys should map BSC distribution, and operators should be required to avoid high-value areas or fund restoration elsewhere. Post-mining reclamation plans must include BSC recovery targets and timelines, with performance bonds ensuring compliance.

Urban planners and transportation agencies can reduce vehicle impacts by restricting off-road travel, hardening routes with gravel or pavement in high-use areas, and enforcing penalties for violations. GPS tracking and remote sensing make enforcement more feasible than ever.

Public education is essential but not sufficient. Hikers who learn to recognize and avoid BSCs make a difference, but systemic change requires policy muscle. Protected areas, restoration funding, and enforceable regulations must back up the goodwill of individuals.

If you live in or visit drylands, start by learning to recognize BSCs. They look like dark, bumpy, or lumpy soil surfaces, often black, brown, or greenish, with visible texture distinct from bare sand or rock. Once you see them, you can't unsee them.

Stay on trails and durable surfaces. If no trail exists, walk on rock, gravel, or already disturbed ground. Avoid camping on BSCs; choose sandy washes or previously used sites instead.

Advocate for BSC protection in land-management decisions. Attend public meetings about grazing permits, mining proposals, or trail development. Ask whether BSC surveys have been conducted and what mitigation measures are planned.

Support organizations working on dryland conservation, restoration ecology, and sustainable land use. Donate, volunteer, or amplify their messages on social media.

For land managers, farmers, and ranchers, explore rotational grazing, fencing, and water management strategies that reduce pressure on BSCs. Engage with extension services, soil conservation districts, and researchers who can provide site-specific guidance.

Policymakers should fund BSC research, mapping, and restoration at scales that match the challenge. The data exists. The techniques are being refined. What's missing is political will and budgets that reflect the importance of these invisible ecosystems.

Desertification threatens food security, water supplies, and livelihoods for billions of people. As climate change accelerates and human populations grow, pressure on drylands will intensify. BSCs won't solve everything, but they represent a low-cost, nature-based solution that works if we let it.

We're finally developing the tools to map, monitor, and restore BSCs at meaningful scales. Machine learning can identify crust types from satellite imagery. Drones can survey large areas quickly. Genetic techniques can match inoculum to local conditions, improving restoration success rates.

But all the technology in the world won't matter if we keep crushing these ecosystems faster than they can recover. The choice is ours: keep treating deserts as empty wastelands, or recognize the hidden power of the living skin that holds them together.

Next time you see a patch of bumpy, blackish soil in the desert, remember: you're looking at a hydrological engineer, a nitrogen factory, and an erosion barrier rolled into one. Step carefully.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

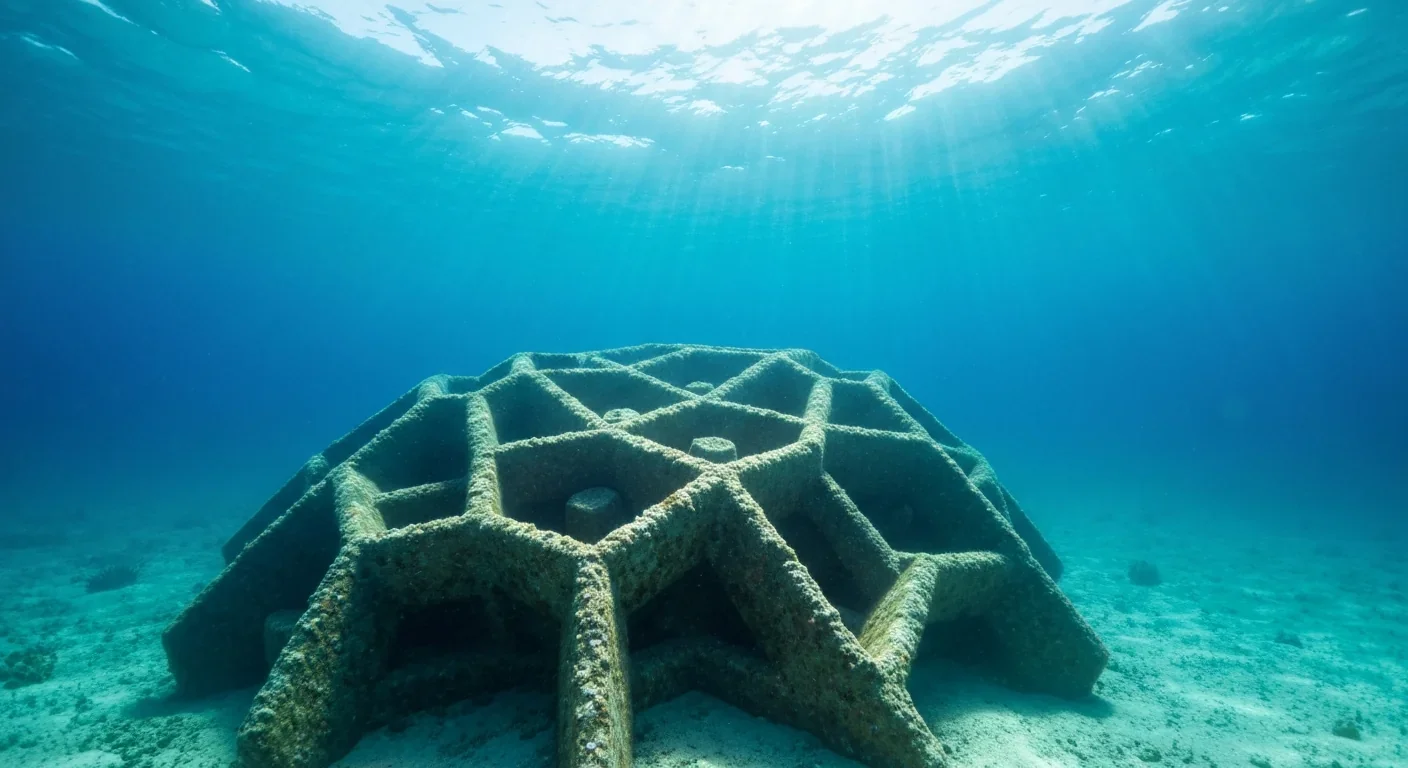

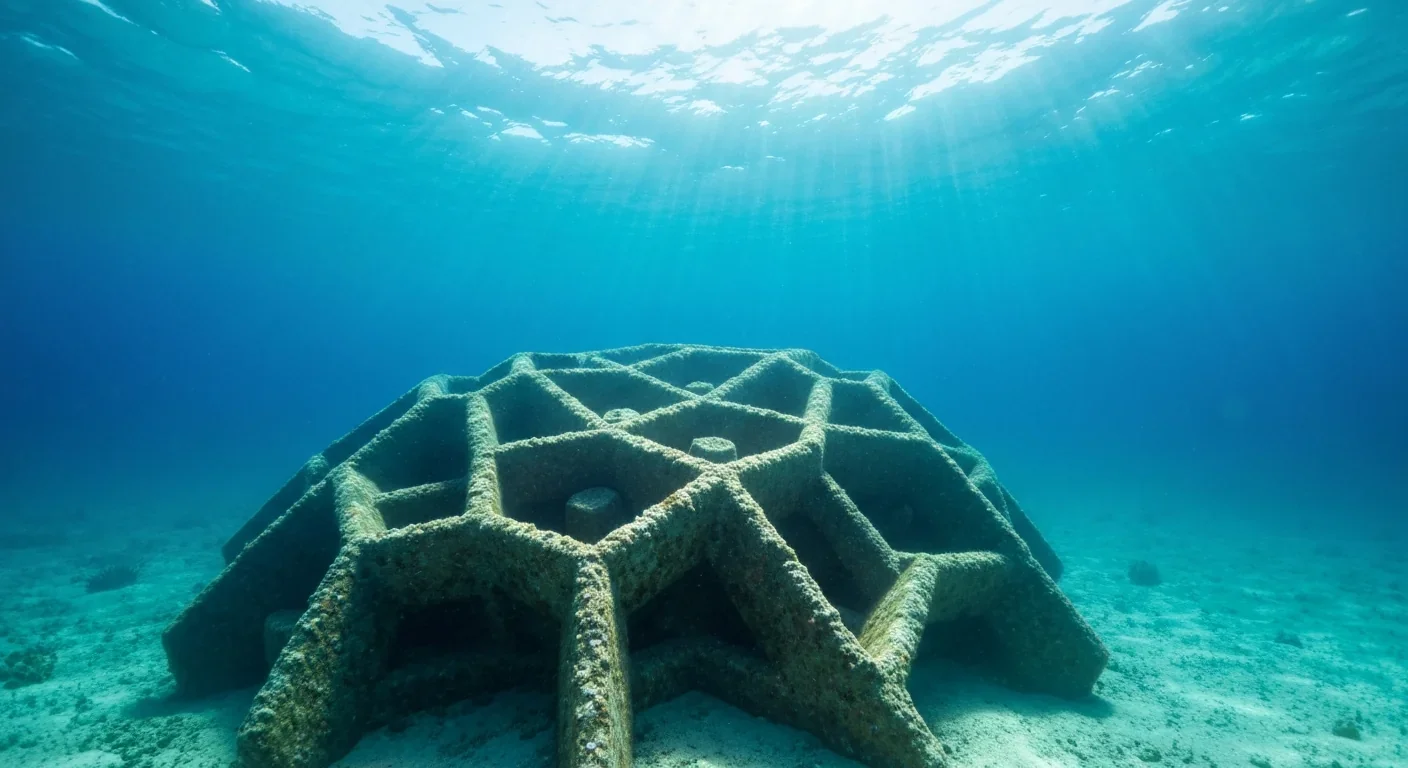

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

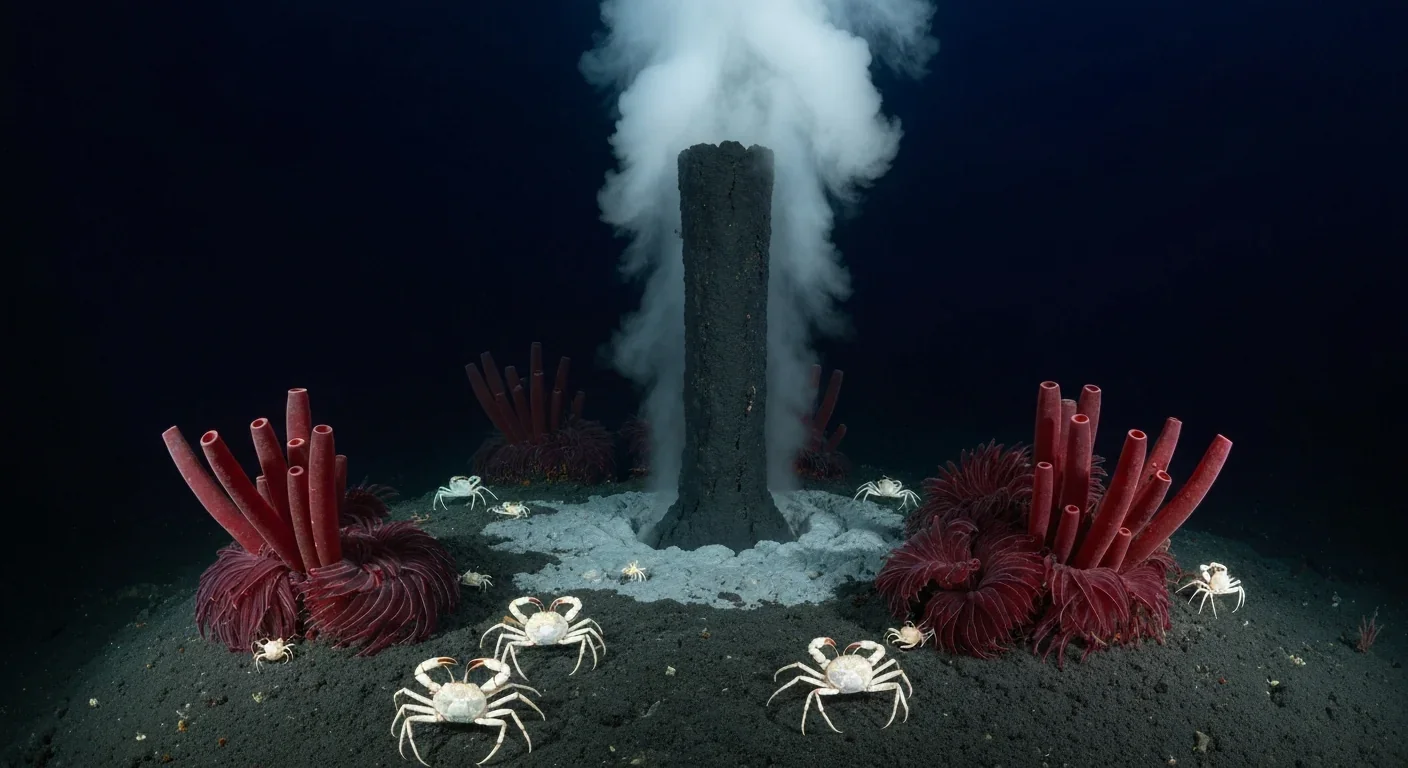

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

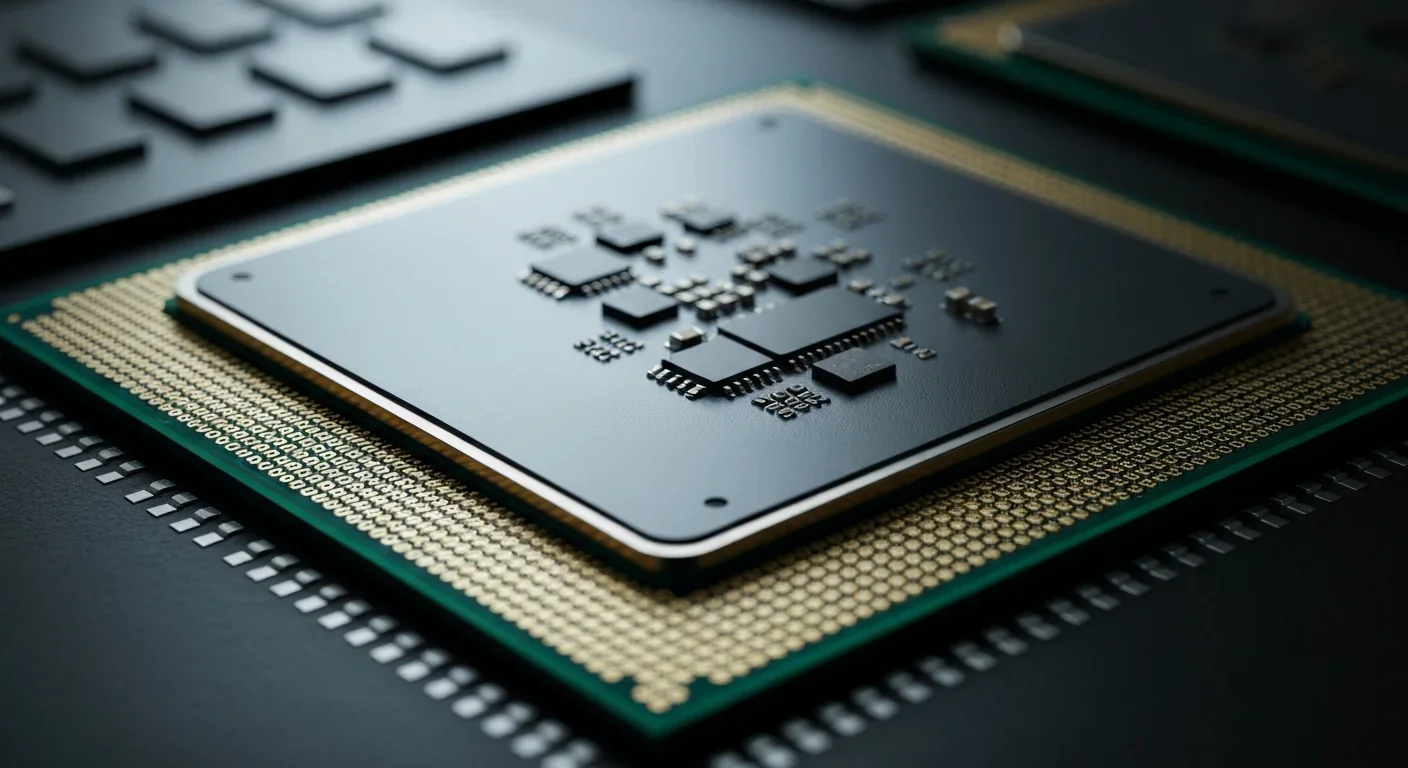

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.