3D-Printed Coral Reefs: Can We Engineer Marine Recovery?

TL;DR: By 2050, 216 million people could be displaced by climate change, yet international law doesn't recognize them as refugees. Pacific islands are sinking, legal frameworks are failing, and we're running out of time to respond with dignity.

By 2050, 216 million people could be forced to move within their own countries because of climate change. That's roughly the combined population of France, Germany, and the United Kingdom, all displaced by rising seas, failed crops, and uninhabitable temperatures. It's not some distant nightmare, it's already unfolding in places like Kiribati, Bangladesh, and the Marshall Islands, where entire communities are planning their exit strategies.

The strange thing is, international law doesn't recognize these people as refugees. They're moving, but they're invisible to the legal frameworks designed to protect displaced populations.

The tiny Pacific nation of Tuvalu is experiencing sea level rise 1.5 times faster than the global average. NASA projects that half of its capital, Funafuti, will be underwater by 2050. This isn't gradual, manageable change. It's existential.

Kiribati faces the same fate. The government has already purchased land in Fiji as an insurance policy for when, not if, their islands become uninhabitable. Over 12,000 Marshallese now live in Springdale, Arkansas, making it the largest Marshallese diaspora outside the Marshall Islands themselves. They're climate refugees in all but name.

What happens when an entire nation loses its territory? Current international law says that statehood cannot continue without a population or natural territory. When these islands go under, their citizens won't just lose their homes, they'll lose their country. They'll become stateless people, adrift in a legal vacuum.

Three forces are driving this crisis, and they're all accelerating.

First, there's sea level rise. Coastal areas housing hundreds of millions of people are becoming increasingly vulnerable. Bangladesh, home to 170 million people packed into river deltas barely above sea level, is already dealing with regular flooding that forces families to constantly adapt and relocate.

Second, extreme weather events are multiplying. Hurricanes, floods, droughts, they're not just more frequent, they're more intense. Communities that once experienced a devastating storm every generation now face them every few years. Recovery becomes impossible when the next disaster hits before you've rebuilt from the last one.

Third, resource scarcity is pushing people to move. Water sources are becoming salinized, farmland is turning to desert, and fish populations are collapsing. When you can't grow food or access clean water, migration isn't a choice, it's survival.

These aren't isolated problems. They compound. Drought drives rural populations into cities, overwhelming infrastructure. Coastal flooding contaminates freshwater supplies. Failed harvests trigger food price spikes that destabilize entire regions.

The vast majority of climate migrants move within their own countries. A farmer in Nepal whose land becomes unproductive moves to Kathmandu. A Bangladeshi fishing family displaced by coastal erosion relocates to Dhaka. These internal migrations strain cities that are already struggling.

Cross-border migration is trickier because there's no legal framework for it. The 1951 Refugee Convention was designed for people fleeing persecution, not environmental catastrophe. Climate change isn't recognized as grounds for refugee status, leaving millions in legal limbo.

Some countries are negotiating bilateral agreements. Australia and Tuvalu signed the Falepili Union, the world's first bilateral climate mobility treaty, which allows up to 280 Tuvaluans to migrate to Australia annually with full rights to work, study, and settle. It's a start, but it only covers one small nation.

Regional patterns are emerging. Pacific islanders are moving to Australia, New Zealand, and the United States. Sub-Saharan Africans facing desertification and drought are heading north toward Europe or into neighboring countries. Central Americans fleeing crop failures and water scarcity move toward the United States.

These aren't desperate masses storming borders. They're families making calculated decisions about where they can build a life when their homeland becomes unlivable.

International law hasn't caught up with reality. The Refugee Convention offers no protection for people displaced by climate change because environmental factors aren't considered persecution. Legal experts describe this as a governance vacuum.

Some argue for expanding the definition of refugee to include climate displacement. Others propose a new international treaty specifically for environmental migrants. A third approach focuses on bilateral and regional agreements, like the Australia-Tuvalu deal.

Each option has problems. Expanding the Refugee Convention could undermine protections for political refugees by diluting the definition. A new treaty would take decades to negotiate and might never achieve broad ratification. Bilateral agreements help individual countries but don't address the systemic nature of the crisis.

Meanwhile, people are moving. The legal frameworks will eventually catch up, probably after millions have already been displaced without protection.

The Compact of Free Association allows Marshallese citizens to live and work in the United States without a visa, but these protections are neither permanent nor comprehensive. When the islands become uninhabitable, what happens to these agreements? Can you return to a country that no longer exists?

Climate migration reshapes economies in complex ways.

For sending countries, it's often catastrophic. Young, working-age people leave, draining the labor force. Tax revenues decline. Economic activity contracts. The people most able to adapt and rebuild are the ones who leave first, creating a downward spiral.

But there are exceptions. Remittances from migrants can be lifelines for communities back home. A Bangladeshi worker in Malaysia or a Pacific islander in New Zealand sends money that supports extended family networks, funds small businesses, and keeps local economies afloat.

For receiving countries, the picture is mixed. Economic analyses suggest that migration can boost GDP when migrants fill labor shortages and bring skills. Australia's deal with Tuvalu includes provisions for education and employment because they recognize the economic value of integrating climate migrants.

But there are real costs too. Housing, healthcare, education, these all require investment. Communities experiencing rapid demographic change can face social tensions. Politicians often exploit these fears, framing climate migrants as threats rather than people seeking safety.

The irony is stark. The countries that contributed most to climate change, wealthy industrialized nations, are the ones most resistant to accepting climate refugees. The countries bearing the brunt of displacement often had minimal historical emissions.

Climate migration creates cascading health crises. Screening in Kiribati revealed rates of diabetes and hypertension among women of childbearing age that exceed comparable populations in Australia or New Zealand. Contaminated water sources, disrupted food systems, and environmental stress are creating public health emergencies.

When people move, they often end up in overcrowded urban slums or displacement camps with inadequate sanitation, limited healthcare, and poor nutrition. Disease spreads quickly in these conditions.

Security concerns are real but often exaggerated. Climate change can exacerbate existing tensions, particularly when resources become scarce. But the idea that climate refugees will trigger mass conflict is mostly fear-mongering. Most migration happens peacefully, even when it's desperate.

The social impact on host communities deserves attention. Rapid demographic change challenges local infrastructure and services. Schools become overcrowded, housing becomes expensive, and social cohesion can fray. These are manageable problems with proper planning and investment, but they require political will.

Some countries are getting creative. Bangladesh has developed cyclone shelters and early warning systems that have dramatically reduced death tolls from storms. They're building floating agriculture systems that can withstand flooding. These adaptation measures buy time, but they're not permanent solutions.

Médecins Sans Frontières is working in Kiribati to rehabilitate contaminated wells and install rainwater harvesting systems. These low-cost interventions improve immediate living conditions and reduce pressure to migrate.

The international community is slowly waking up. Climate adaptation funding is increasing, though it remains far below what's needed. The UN has established a Loss and Damage Fund to compensate countries for climate impacts, but the funding mechanisms are still being negotiated.

Some cities are implementing managed retreat, buying out homeowners in flood-prone areas and restoring natural barriers like wetlands. It's expensive and politically difficult, but it's more humane than waiting for disasters to force people out.

Universities and think tanks are studying the problem. Researchers are tracking migration patterns to help policymakers anticipate where people will move and plan accordingly. This kind of forward-looking analysis is essential for managing what's coming.

We need legal frameworks that recognize climate displacement as a distinct category requiring protection. This doesn't mean abandoning the Refugee Convention, it means updating our legal architecture to match 21st-century realities.

We need substantial increases in climate adaptation funding. The current commitments are nowhere near adequate for the scale of the challenge. Wealthy nations that benefited from fossil fuel development have a moral and practical obligation to help vulnerable countries adapt.

We need regional cooperation agreements that establish orderly pathways for climate migration. The Australia-Tuvalu treaty is a model, even if it's imperfect. Southeast Asian nations, Pacific island countries, and African regional bodies should be negotiating similar arrangements.

We need to invest in resilience and adaptation in vulnerable countries. Helping people stay home when possible is better than managing mass displacement. This means climate-resilient agriculture, water infrastructure, coastal defenses, and early warning systems.

We need to reframe the conversation. Climate migrants aren't invaders or burdens, they're people whose homes are becoming uninhabitable through no fault of their own. Many bring skills, education, and determination. Countries that welcome and integrate them effectively will benefit.

Individual action matters less here than collective political will, but there are still meaningful steps.

Support organizations working on climate adaptation in vulnerable regions. Groups like the International Organization for Migration and NGOs focused on climate resilience are doing essential work.

Advocate for policy changes. Contact your representatives about climate adaptation funding, international cooperation on migration, and expanding legal protections for climate refugees.

Educate yourself about the human stories behind the statistics. First-person accounts from climate migrants make the crisis real in ways that numbers can't.

Support local integration efforts if climate migrants settle in your community. Welcoming newcomers, supporting language programs, and pushing back against anti-immigrant rhetoric all matter.

Most importantly, recognize that climate displacement is fundamentally a climate problem. The ultimate solution is dramatically reducing greenhouse gas emissions to slow the changes forcing people to move. Everything else is managing the consequences of our failure to act sooner.

We're in the early stages of what will be the defining migration crisis of the century. The 216 million projected internal migrants by 2050 is a conservative estimate. It assumes moderate climate scenarios and doesn't fully account for cascading effects or feedback loops.

Some researchers think the real number could be double or triple that. We don't really know because we've never seen displacement at this scale driven by environmental change.

What we do know is that it's happening now. Families in Tuvalu are teaching their children to speak English because they know they'll likely grow up in Australia or New Zealand. Farmers in Bangladesh are learning new trades because their land is disappearing under saltwater. Young people in the Marshall Islands are deciding between staying on islands that might not exist in 30 years or building lives elsewhere.

These aren't future scenarios. They're present realities. The question isn't whether millions will be displaced by climate change, it's whether we'll build the systems to manage that displacement with dignity and justice, or whether we'll let it unfold as a series of humanitarian catastrophes.

Right now, we're heading toward the second option. But we still have time to choose differently.

The people already moving because of climate change are showing us what's coming. The least we can do is pay attention and respond with the seriousness this crisis demands. Their futures depend on decisions being made today, in capitals and courtrooms and conference halls far from the places where rising seas are already swallowing the land.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

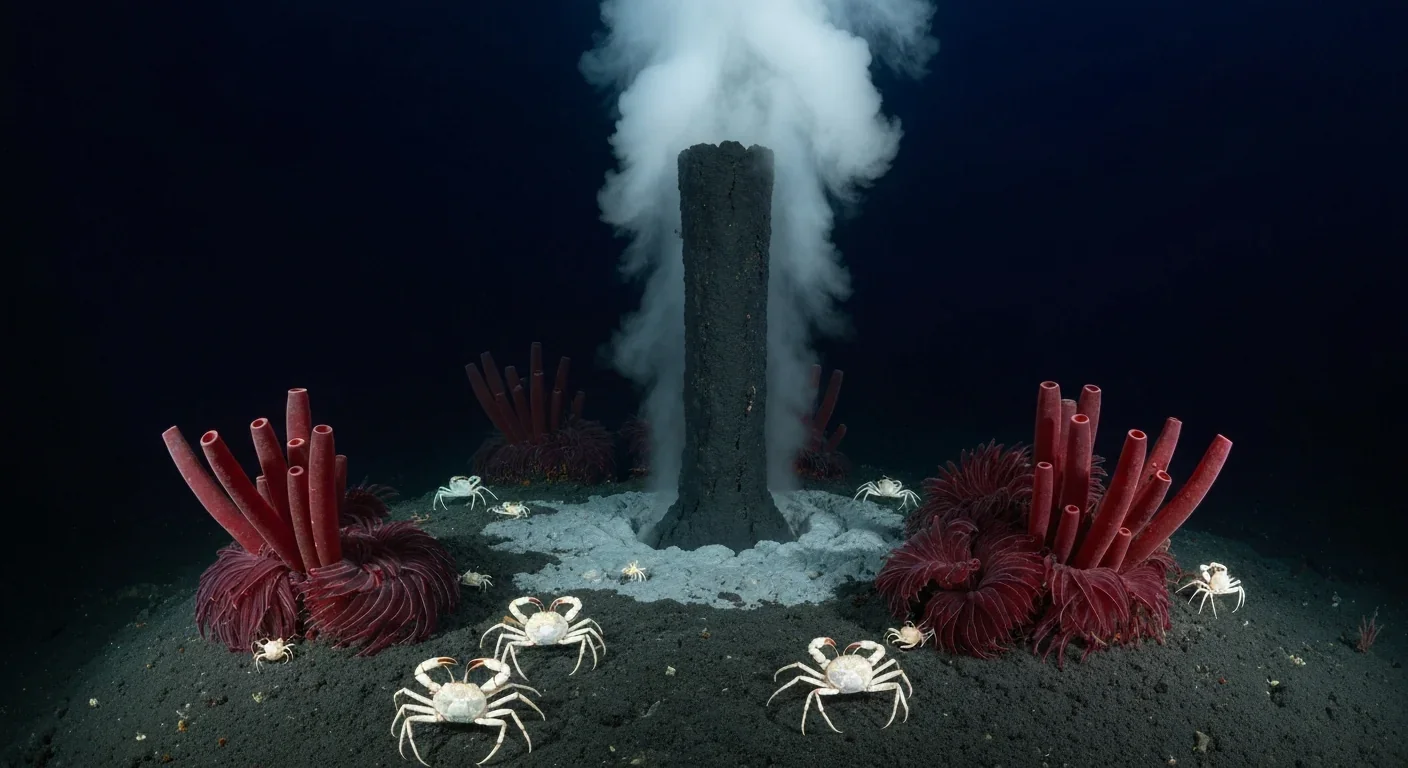

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

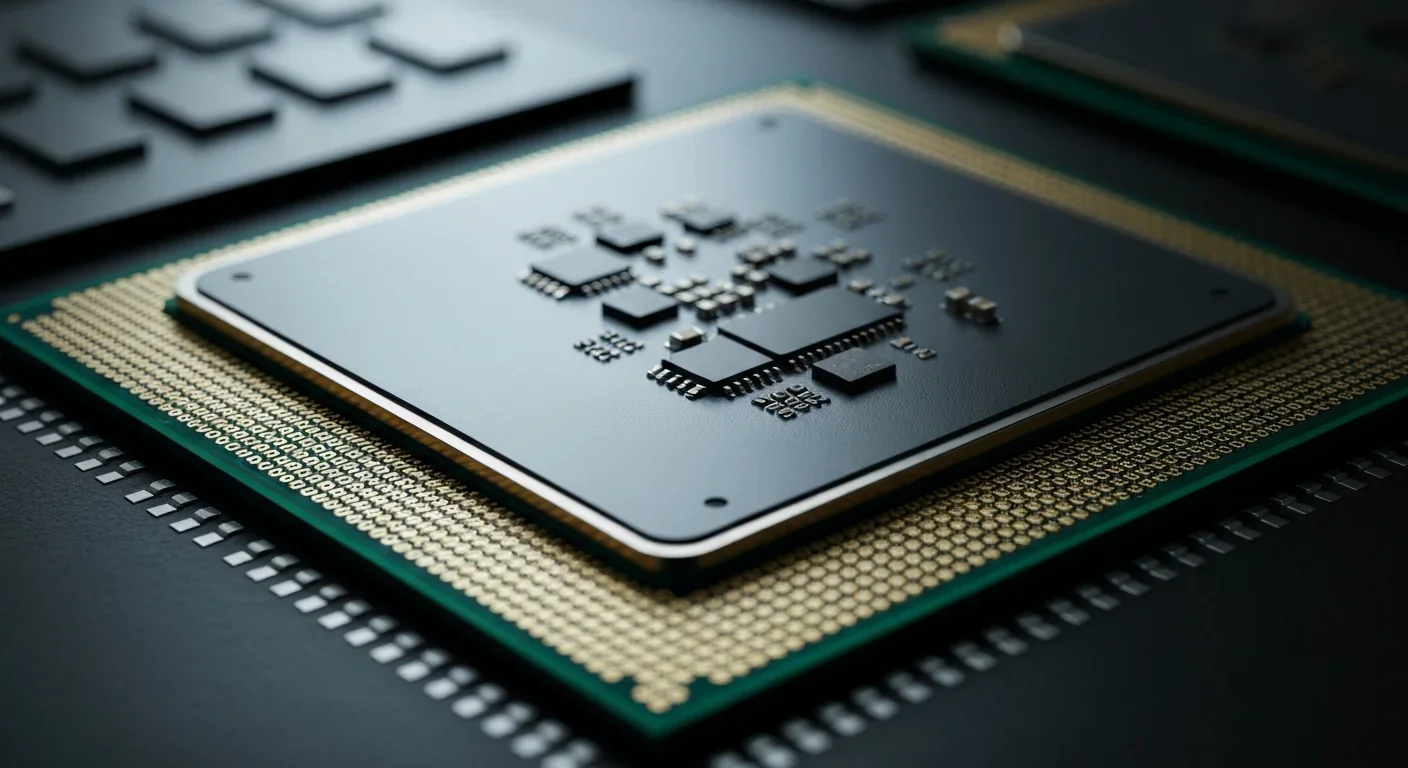

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.