3D-Printed Coral Reefs: Can We Engineer Marine Recovery?

TL;DR: Coastal dune restoration is proving more effective and affordable than traditional seawalls for protecting shorelines from rising seas. Using native grasses, strategic fencing, and natural sand dynamics, communities worldwide are building flexible barriers that cost less, last longer, and provide multiple environmental benefits.

By 2050, over 200 million people living along coastlines will face chronic flooding from sea level rise. Hard infrastructure like seawalls and concrete barriers cost millions and often fail within decades, pushing erosion onto neighboring shores. But coastal communities worldwide are discovering a counterintuitive truth: the most effective flood defense doesn't come from engineering firms. It comes from sand, salt-tolerant grasses, and strategic fencing. Dune restoration projects are transforming vulnerable shorelines into resilient natural barriers, protecting billions in property while costing a fraction of traditional methods. What started as experimental conservation work has become a proven model for climate adaptation - one that works with nature instead of against it.

Coastal dunes function as dynamic shock absorbers between ocean and land. Unlike rigid structures that crack under repeated wave assault, dunes flex and reform, dissipating storm energy through their porous structure. The secret lies in their composition: multiple layers of sand held together by deep root networks from native grasses like American beachgrass, sea oats, and dune panic grass.

When storm surge hits a healthy dune, the first wave washes over the crest, losing momentum as water filters through sand. Subsequent waves encounter resistance from vegetation that bends but doesn't break. The dune itself may lose several feet of sand on its seaward face, but the root systems prevent catastrophic collapse. After the storm passes, wind patterns naturally deposit sand back onto the dune, beginning recovery.

Research from North Carolina's Outer Banks demonstrates that dune age and internal structure dramatically affect resilience. Older dunes with established root systems extending 6-8 feet deep withstand Category 3 hurricanes with minimal damage. Younger dunes, planted within the past 5-10 years, still provide substantial protection but may require rebuilding after major storms.

The protective capacity isn't just theoretical. During Hurricane Sandy in 2012, communities along the New Jersey coast with restored dune systems experienced 65% less property damage than areas with degraded or absent dunes. The dunes absorbed wave energy that would otherwise have destroyed homes and infrastructure blocks inland.

Modern dune restoration combines traditional ecological knowledge with contemporary engineering. The process typically begins with sand fencing - parallel rows of wooden slats that slow wind velocity near the ground, causing airborne sand to settle rather than blow away. As sand accumulates around the fences, workers plant native grasses in precise patterns.

Species selection matters enormously. New Zealand learned this the hard way after initially using exotic marram grass for dune stabilization. The grass created tall, steep dunes that looked impressive but collapsed during storms. Native species like pingao and Spinifex create lower-angle, more stable formations that handle wave action far better. The country has since transitioned to native plantings, with measurably improved storm performance.

Planting density and timing also affect success rates. Optimal spacing places grass clumps 18-24 inches apart in a grid pattern, allowing each plant's root system to expand without competing for nutrients. Planting during cooler months gives roots time to establish before summer heat and tourist foot traffic stress new growth.

Sand fencing techniques have evolved significantly. Traditional vertical slat fences work well for initial accumulation, but newer designs incorporate angled sections that direct sand deposition to specific areas. Some restoration projects use biodegradable coir logs - compressed coconut fiber tubes that hold shape long enough for vegetation to establish but eventually decompose rather than becoming litter.

The Gold Coast in Australia demonstrates how strategic dune management balances recreation with protection. The city maintains designated pathways with elevated boardwalks, concentrating foot traffic away from sensitive vegetation. Fenced restoration zones allow dunes to rebuild naturally while still providing beach access. This approach maintains tourism revenue while strengthening coastal defenses.

Florida's Pinellas County recently completed a $125 million beach and dune restoration project following hurricane damage. Rather than rebuilding seawalls, engineers pumped millions of cubic yards of sand onto eroded beaches and constructed new dune systems with native plantings. The project includes ongoing monitoring to track vegetation establishment and sand movement patterns.

Flagler County, Florida, took a different approach by working with private property owners to secure easements for dune restoration on residential shorelines. This public-private partnership model allows restoration on land that would otherwise remain vulnerable, extending protective barriers across previously fragmented coastlines.

In the Netherlands, coastal managers pioneered "dynamic dune restoration" that deliberately allows limited dune migration. Rather than completely stabilizing dunes in fixed positions, they permit natural movement patterns while controlling direction through strategic planting and sand management. This creates more resilient systems that adapt to changing wind and wave conditions.

China's northwestern deserts face different challenges - shifting sands threatening infrastructure rather than storm surge. Researchers there successfully stabilized active dunes using native grasses adapted to arid conditions. The techniques developed for inland dunes have applications for coastal restoration in arid climates where traditional salt marsh plants struggle.

Naples Botanical Garden in Florida transformed a degraded beach into a demonstration restoration site that doubles as education space. Visitors learn about native dune plants, proper beach behavior to protect vegetation, and the connection between healthy dunes and storm protection. The project shows how restoration can serve multiple community goals beyond just coastal defense.

Traditional hard infrastructure carries hidden costs that dune restoration avoids. A concrete seawall protecting a mile of shoreline might cost $5-10 million to construct, requires maintenance every 15-20 years, and often accelerates erosion on adjacent properties. Communities end up paying for the downstream effects of their own protection efforts.

Dune restoration for equivalent shoreline coverage typically costs $500,000-$2 million, depending on site conditions and labor costs. Maintenance involves periodic replanting and fence repair, but established systems become largely self-sustaining within 5-7 years. The cost differential becomes even more favorable over time as natural systems adapt and strengthen rather than degrading.

The World Bank analyzed coastal protection investments in tourism-dependent regions and found nature-based solutions delivered better long-term returns. Beach and dune restoration maintained tourism revenues while reducing disaster recovery costs. Hard infrastructure sometimes protected immediate coastal assets but damaged the beach amenities that attracted tourists in the first place.

Insurance markets are starting to recognize these differences. Some coastal property insurers offer premium reductions for homes protected by certified dune restoration projects, similar to discounts for hurricane shutters or reinforced roofing. This creates financial incentives for property owners to support restoration efforts.

Federal and state funding increasingly prioritizes nature-based solutions. NOAA's Restoration and Nature-Based Solutions programs provide grants and technical assistance for coastal communities pursuing dune restoration. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act allocated billions for coastal resilience, with preference for projects demonstrating multiple benefits - flood protection, habitat creation, recreation access.

Successful restoration requires more than good techniques and adequate funding. It demands legal frameworks that protect restored dunes from development pressure and community buy-in from residents who use beaches recreationally.

Many coastal states now mandate setback distances for new construction, requiring buildings to be placed a minimum distance from the high tide line. These regulations preserve space for dune formation and migration. Some jurisdictions prohibit removing sand or vegetation from designated restoration zones, with fines for violations.

Public access presents one of the trickiest policy challenges. People want to enjoy beaches, but foot traffic destroys the vegetation that stabilizes dunes. The solution involves strategic access points with defined pathways, elevated walkways over sensitive areas, and education about staying on designated routes. Signage explaining why restrictions exist increases voluntary compliance dramatically.

Community involvement transforms restoration from a top-down government project into shared ownership. Volunteer planting events build connection between residents and their coastline. School groups that participate in restoration develop understanding about coastal processes that shapes future beach behavior. Surf clubs and fishing groups often become restoration advocates once they understand how healthy dunes support the recreational resources they value.

Tourism-dependent communities initially worry that dune restoration will make beaches less attractive or accessible. Experience shows the opposite. Well-designed restoration enhances beach experiences by creating natural beauty, providing habitat for shorebirds and sea turtles, and reducing erosion that narrows usable beach area. Marketing beach communities as environmentally responsible destinations appeals to growing numbers of eco-conscious travelers.

Current dune restoration designs work well for present conditions and near-term sea level projections. But climate models suggest acceleration in coming decades that could outpace natural dune building. Adaptation strategies are already evolving.

"Managed retreat" sounds defeatist but simply means moving development away from the most vulnerable shorelines, allowing dune systems space to migrate landward as seas rise. Communities in the Outer Banks and Cape Cod have begun buying out the most at-risk properties, converting them to conservation land where dunes can expand naturally.

Some restoration projects now incorporate higher elevations than historical dune heights, building in extra capacity for future storm surge. This requires more sand placement initially but creates additional protection margin as seas rise.

Hybrid approaches combine natural and engineered elements. TrapBag systems - sand-filled geotextile containers - can form a storm-resistant core while vegetation grows on the seaward face. The bags provide immediate protection while the natural dune develops around them. If designed properly, the artificial core becomes invisible within 2-3 growing seasons.

Research into salt-tolerant plant species continues as rising seas increase salinity in dune ecosystems. Breeding programs are selecting for grasses that maintain strong root systems in higher-salt conditions. Some restoration projects now use mixed plantings that include species currently found further south, anticipating range shifts as climate changes.

Dynamic monitoring allows adaptive management. Drone surveys track vegetation coverage and sand volume changes. When monitoring reveals erosion hotspots or vegetation failure, managers can intervene quickly rather than waiting for catastrophic damage. This responsive approach maintains protection even as conditions change.

The shift toward nature-based coastal protection represents more than just a technical change in flood defense strategies. It signals a broader recognition that human engineering alone cannot overcome natural forces of the scale climate change is unleashing.

Dune restoration succeeds because it works with natural processes rather than trying to dominate them. Sand moves, vegetation grows and dies, dunes erode and rebuild - these cycles continue regardless of human preference. Smart coastal management harnesses these processes, directing them toward protective outcomes while accepting that absolute control is impossible.

The economic case strengthens as climate impacts intensify. Every dollar spent on prevention reduces future disaster recovery costs by an estimated four to six dollars. Communities investing in dune restoration now are essentially buying insurance against catastrophic flooding, except the premium buys permanent improvements rather than just coverage.

Perhaps most importantly, restored dunes provide benefits beyond flood protection. They create habitat for endangered species like piping plovers and sea turtles. They filter stormwater runoff before it enters the ocean. They offer recreational and aesthetic value that enhances quality of life and property values. This multiplier effect makes restoration investment far more valuable than single-purpose infrastructure.

As more communities implement restoration projects and share results, the knowledge base improves rapidly. Techniques that failed get discarded, successful approaches get refined and replicated. What began as experimental ecology is maturing into proven engineering practice, backed by decades of performance data and increasingly sophisticated modeling.

The coastline is changing. The choice facing coastal communities isn't whether to respond but how - with brittle, expensive infrastructure that fights nature, or flexible, affordable systems that channel natural processes toward human goals. The evidence suggests sand and grasses, properly managed, outperform concrete and steel. That's not romanticism about nature. It's just engineering informed by reality.

Millions of people live where land meets sea. Their homes, businesses, and communities face growing threats from rising water and intensifying storms. The solution is literally under their feet - it just needs to be rebuilt, protected, and given room to do what dunes have done for millennia. The question isn't whether dune restoration works. It's whether we'll implement it widely enough, quickly enough, to make a difference before the water rises too far.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

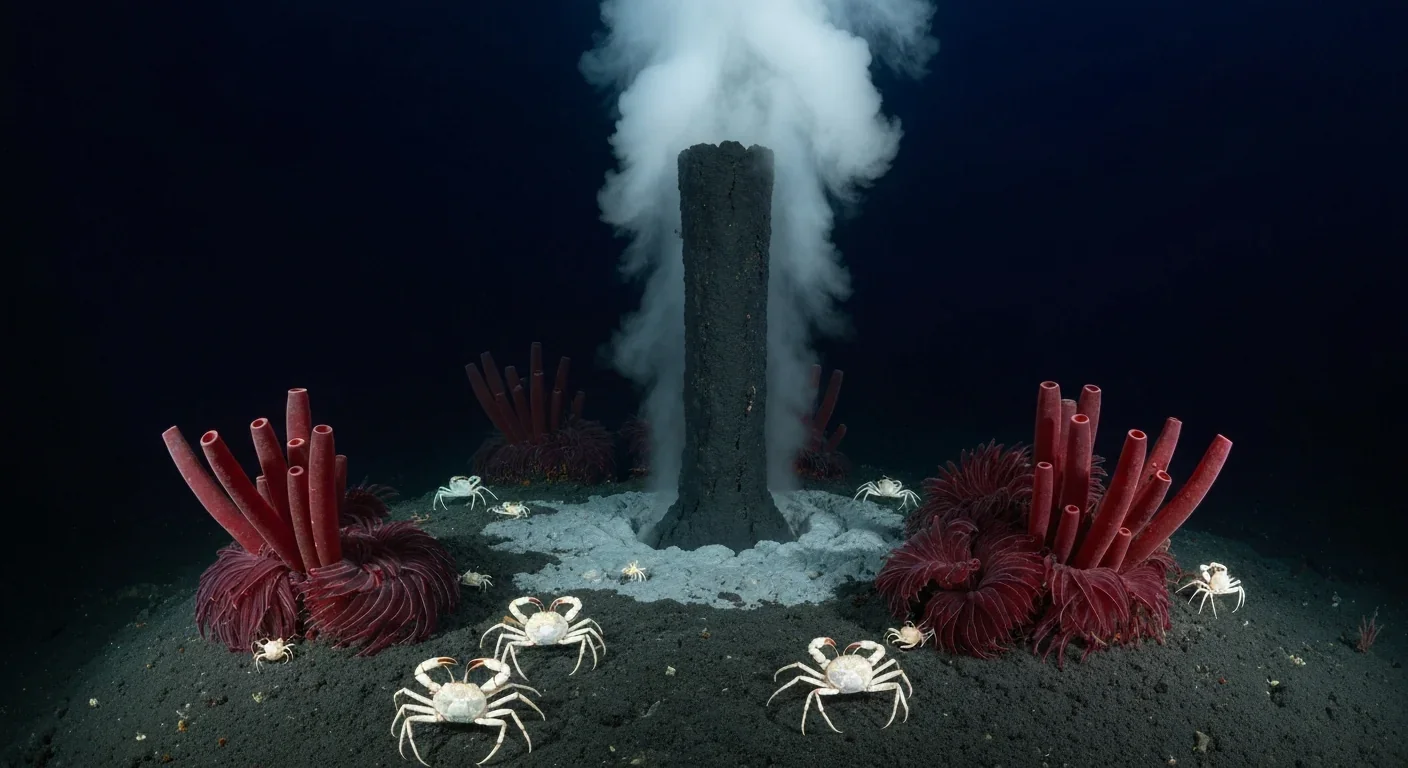

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

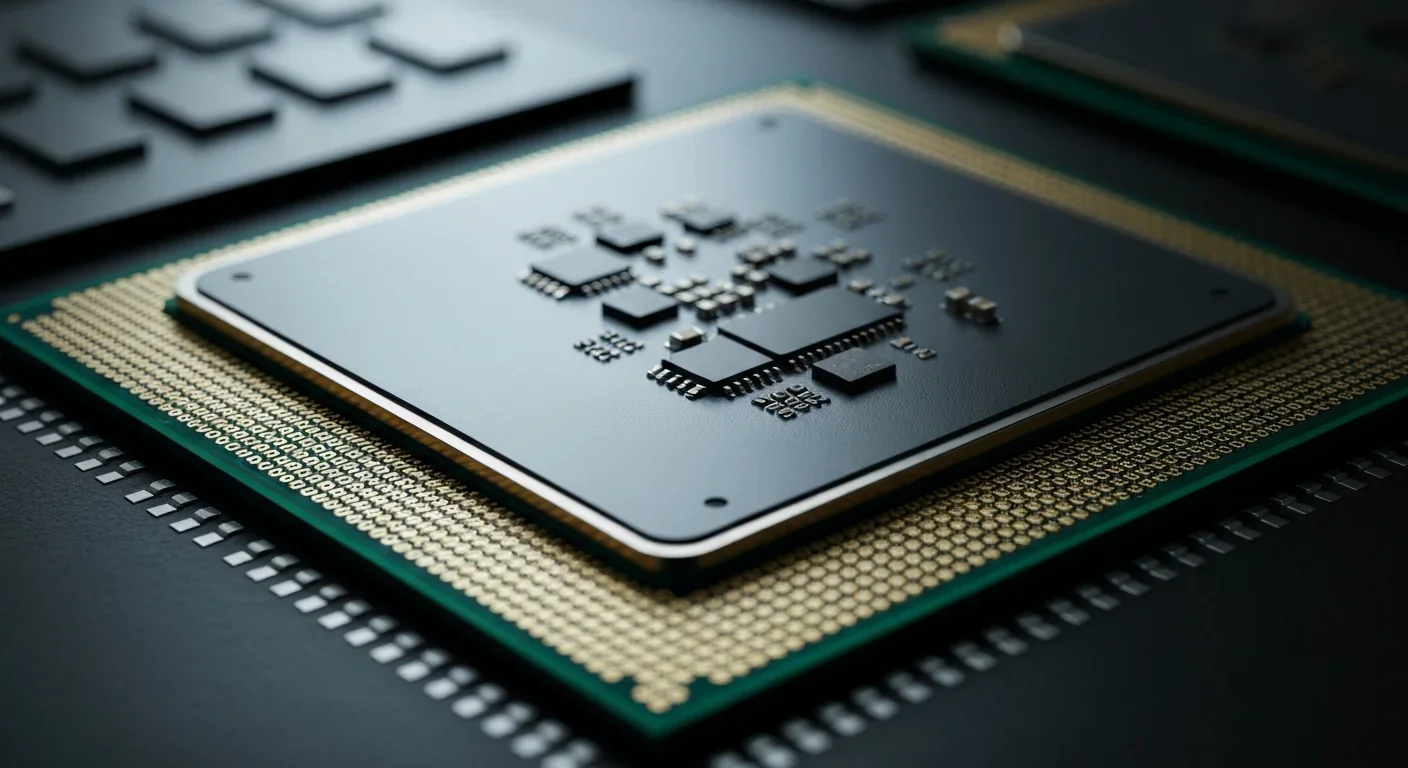

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.