3D-Printed Coral Reefs: Can We Engineer Marine Recovery?

TL;DR: Digital pollution taxes could transform the data center industry by making environmental costs visible, driving a technology sprint toward renewable energy and efficiency innovations while reshaping the global geography of cloud computing.

Every time you ask ChatGPT a question, somewhere in Virginia or Texas, a server farm gulps down enough electricity to power a small town for a day. By 2030, data centers will consume 945 terawatt-hours annually, double what they use today. That's more energy than entire nations burn through. And here's the uncomfortable truth: actual emissions are probably 662% higher than Big Tech admits. We've built an invisible infrastructure that's choking the planet, and most people have no idea it exists.

What if we made the cloud expensive to pollute?

A growing movement wants to tax digital pollution the same way we tax carbon from cars and factories. It's a radical idea that could either accelerate the green tech revolution or kneecap the digital economy. The stakes couldn't be higher, because AI is about to make everything worse.

Let's start with something you probably don't think about: the physical reality of the internet. Every Instagram story, every Netflix binge, every late-night Wikipedia rabbit hole runs through massive warehouses filled with computers that never sleep. These data centers now account for roughly 1-2% of global electricity consumption, a number that sounds small until you realize it's equivalent to the entire aviation industry's carbon footprint.

Goldman Sachs projects a 165% increase in data center power demand by 2030, driven almost entirely by artificial intelligence. Training a single large language model can emit as much carbon as five cars over their entire lifetimes. And we're not training one model, we're training thousands, then running billions of queries through them every day.

The numbers get worse when you look at where these facilities actually get their power. Despite tech companies' loud commitments to renewables, data centers in Virginia, Texas, and California top the charts for CO2 emissions because they're plugged into grids still dominated by fossil fuels. The gap between corporate sustainability pledges and physical reality has become a canyon.

Here's what researchers found: Big Tech has been using creative accounting to mask its environmental impact. They buy renewable energy credits while their actual data centers run on coal and natural gas. One analysis concluded that if you measure actual grid emissions rather than offset purchases, the industry's carbon footprint is seven times larger than reported.

This accounting sleight of hand can't last forever. As AI demands explode and grids strain under the load, policymakers are starting to ask a question that makes tech executives nervous: Should companies pay for the environmental damage their digital infrastructure causes?

The concept isn't as exotic as it sounds. We've taxed pollution for decades, from carbon levies on factories to fees on plastic bags. Digital pollution taxes simply extend that logic to the cloud.

Most proposals focus on one of two approaches. The first taxes energy consumption directly, charging data centers per kilowatt-hour above a certain threshold or efficiency standard. The second taxes carbon emissions, calculated from the actual grid mix powering each facility. Some combine both, creating a two-tier system that rewards renewable energy adoption while penalizing inefficiency.

France and Austria have already experimented with adjacent concepts through their digital services taxes, though these focus on revenue rather than environmental impact. Austria's tax on digital advertising raised €103 million in 2023, a modest sum that barely registered in government budgets. But it established a precedent: digital operations can be taxed based on their externalities.

A true digital pollution tax would work differently. Instead of targeting revenue, it would measure actual environmental impact using metrics like Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE), a ratio comparing total facility power to computing equipment power. Modern hyperscale data centers achieve PUE scores around 1.2, meaning only 20% of energy goes to cooling and infrastructure rather than computation. Legacy facilities often hit 2.0 or worse, wasting half their power on overhead.

The tax structure could reward efficiency by setting thresholds: facilities below 1.3 PUE pay a lower rate, those above 1.8 pay premium rates. Add in a carbon multiplier based on grid emissions intensity, and suddenly there's a powerful incentive to both improve efficiency and relocate to regions with clean grids.

Denmark has floated a variation targeting water consumption, since data centers guzzle enormous quantities for cooling. In water-stressed regions, this matters as much as energy. A comprehensive digital pollution tax might bundle energy, carbon, and water into a single environmental impact score.

If implemented globally, digital pollution taxes would fundamentally reshape the economics of cloud computing. Consider the math: a hyperscale data center consuming 100 megawatts pays roughly $50-80 million annually for electricity. Apply a carbon tax of $50 per ton to emissions from fossil fuel sources, and facilities on dirty grids could see energy costs jump 30-50%.

For companies operating on thin margins, that's existential. It would make operating in coal-heavy regions like parts of China or India dramatically more expensive than running facilities in Norway or Iceland, where geothermal and hydro provide nearly carbon-free power. One analysis found that improving PUE from 2.0 to 1.3 could cut operational costs by 35%, incentive enough even without taxes.

Cloud service prices would almost certainly rise, though probably not as much as industry lobbyists claim. The hyperscalers, Google, Amazon, Microsoft, operate at such scale that they could absorb moderate tax increases while still maintaining profitability. Smaller providers might get squeezed, accelerating industry consolidation.

There's a precedent here. When Europe implemented strict data privacy regulations through GDPR, tech companies screamed that compliance costs would cripple innovation. What actually happened? Large companies invested in compliance infrastructure and passed modest costs to customers. Small fly-by-night operations shut down. The industry adapted and kept growing.

Regions piloting carbon pricing have seen similar patterns. Sweden's carbon tax, now at $130 per ton, didn't destroy its economy; it accelerated clean energy adoption and spawned new green tech industries. Finland, Switzerland, and the Netherlands followed similar paths.

The real economic impact might be geographic redistribution. Data centers would migrate toward locations with three advantages: cool climates (less cooling energy), clean grids (lower carbon taxes), and political stability (regulatory certainty). Think Scandinavia, Canada, Iceland, and New Zealand. Places with hot climates and coal-heavy grids would become economic dead zones for cloud infrastructure.

This creates winners and losers among nation-states. Countries that invested early in renewable grids suddenly have a competitive advantage in attracting digital infrastructure investment. Those that didn't face a choice: rapidly decarbonize or watch the industry flee.

The lobbying war over digital pollution taxes has already begun, though it's playing out behind closed doors rather than in public. Tech industry groups argue that targeted environmental taxes would amount to double taxation, since many jurisdictions already have carbon pricing mechanisms. They're pushing instead for voluntary commitments and industry self-regulation.

Environmental advocates counter that voluntary pledges have failed spectacularly. Despite loud net-zero commitments from every major tech company, actual emissions keep rising because AI demand outpaces efficiency gains. Greenpeace has been particularly harsh, calling out Microsoft, Google, and Amazon for "climate hypocrisy" in using renewable energy credits to mask fossil fuel dependence.

The tax policy debate has gotten technical and fierce. How do you measure emissions from facilities that share power with other buildings? What about data centers that use waste heat for district heating systems? Should colocation facilities be taxed differently than hyperscale operations?

Some proposals include exemptions for essential services, arguing that taxing hospital records systems or financial transaction processing differently than entertainment streaming makes moral sense. Others worry that carving out exceptions creates loopholes and gaming opportunities.

International coordination presents another massive challenge. If Europe implements strict digital pollution taxes but Asia doesn't, companies will simply move operations to avoid the levy. This triggered the same problem digital services taxes faced, where unilateral action by individual countries created a fragmented global landscape vulnerable to regulatory arbitrage.

The OECD has floated the idea of a coordinated global framework, similar to its work on corporate minimum taxes. Get enough countries to commit simultaneously, and the race-to-the-bottom dynamic weakens. But achieving that level of international cooperation on a novel tax category seems optimistic, especially given geopolitical tensions.

Meanwhile, some tech companies are quietly hedging their bets. Rather than fight the concept outright, they're trying to shape implementation details in their favor. Microsoft, for instance, has supported carbon pricing in principle while lobbying for gradual phase-ins and credits for renewable energy investments. It's the classic strategy: accept the inevitable but slow it down and water it down.

Here's where the story gets interesting. Taxes don't just punish bad behavior, they supercharge innovation to avoid the tax. A meaningful digital pollution levy could trigger a technology sprint that makes today's efficiency improvements look quaint.

Microsoft has already started building data centers with wood to reduce embodied carbon in construction materials. It sounds bizarre until you understand that concrete and steel production generate enormous emissions, so using engineered timber for structural elements cuts the carbon footprint of construction by 35% or more.

Water cooling innovations are advancing rapidly. Microsoft announced next-generation facilities that consume zero water for cooling, using advanced air cooling and waste heat recovery instead. These systems cost more upfront but would largely dodge water-based pollution taxes.

Some companies are pursuing even wilder solutions. One startup is building data centers that run exclusively on "stranded" renewable energy, basically setting up operations next to wind and solar farms that produce more power than local grids can absorb. They pay rock-bottom rates for energy that would otherwise be wasted, then use that cost advantage to undercut competitors.

The drive for improved Power Usage Effectiveness is accelerating. Google claims some facilities now achieve PUE scores as low as 1.1, meaning just 10% overhead. Getting there requires sophisticated AI-powered cooling management, optimized airflow design, and waste heat recovery systems that capture thermal energy for reuse.

There's even serious research into liquid cooling for chips, submerging servers in non-conductive fluids that absorb heat more efficiently than air. It sounds like science fiction but is already deployed in some high-performance computing centers. Scale that to hyperscale data centers and you could slash cooling energy by 40%.

Perhaps most importantly, a pollution tax would accelerate the shift to renewable power purchase agreements. Tech companies are already the largest corporate buyers of renewable energy, but their commitments would intensify dramatically if every kilowatt-hour of fossil fuel power cost 30-50% more through taxes.

This creates a fascinating feedback loop. As data center operators commit to larger renewable energy purchases, they provide guaranteed demand that makes new wind and solar projects financially viable. That accelerates grid decarbonization, which reduces everyone's tax burden, which makes the economics even better. Sweden and Denmark have already seen this pattern with their carbon taxes.

Not every country faces digital pollution taxes from the same starting position. The policy could accelerate existing inequalities or, designed thoughtfully, help level the playing field.

Wealthy nations with substantial renewable energy infrastructure, think Scandinavia, Canada, parts of Western Europe, would become even more attractive for data center investment. They already benefit from cool climates that reduce cooling loads. Add abundant hydro, wind, or geothermal power and suddenly they're the obvious choice for any company trying to minimize tax exposure.

Developing nations face a harder path. Countries investing heavily in coal power to meet surging electricity demand would see data center investment dry up overnight if global pollution taxes materialized. This matters because data center jobs are high-paying and the infrastructure supports digital economy growth.

But there's a counterargument: developing nations might leapfrog to renewables faster if digital pollution taxes change the economics. Just as many countries skipped landline telephone networks and went straight to mobile, they could skip fossil fuel grids and build renewable-first infrastructure to attract digital investment. Several African nations are already exploring this path, positioning themselves as future green tech hubs.

Climate justice advocates raise a different concern: who bears the cost? If pollution taxes raise cloud service prices, that hits everyone who depends on digital services, including schools, small businesses, and individuals in developing countries. The tax intended to punish polluters ends up as a regressive levy on digital access.

One solution is to recycle tax revenue into subsidies for renewable energy infrastructure in developing regions, creating a virtuous cycle where polluters fund the buildout of clean alternatives. But that requires international cooperation and trust that money will be used as intended, both in short supply.

China presents a special case. The country operates massive data center infrastructure, much of it powered by coal, but has also invested heavily in renewable energy manufacturing and deployment. How China responds to global digital pollution tax pressure could determine whether the policy succeeds or fragments into regional blocs with incompatible rules.

There's also a question of fairness in historical emissions. The West built its digital infrastructure when nobody worried about carbon footprints. Is it fair to now impose taxes that prevent developing nations from following the same path? Climate negotiators have wrestled with this problem for decades without resolution.

The most likely scenario isn't a single global digital pollution tax emerging overnight. Instead, we'll probably see a patchwork of regional experiments that slowly converge or compete.

The European Union has the regulatory appetite and political capital to implement a comprehensive scheme within the next 3-5 years. They've already pioneered carbon border adjustment mechanisms for imports; extending that logic to digital services isn't a huge leap. Several EU members already operate carbon pricing systems they could expand to explicitly cover data centers.

California might move independently in the US, as it often does on environmental policy. The state's grid is increasingly renewable, giving local data centers a competitive advantage if pollution-based taxation arrives. Other blue states could follow, creating a fragmented American market.

Asia remains the wildcard. Japan and South Korea might align with Western approaches, while China pursues its own system tied to domestic policy goals. India, with its coal-dependent grid and booming digital economy, faces tough choices.

For the tech industry, the smart play is to get ahead of regulation rather than fight it. Companies already investing heavily in efficiency and renewables will have a seat at the table shaping policy details. Those still burning coal and hoping for the best will end up with rules written by their competitors.

Within a decade, we'll likely see some form of environmental accounting baked into data center economics, whether through explicit taxes, expanded carbon markets, or regulatory efficiency mandates that function like taxes. The exact mechanism matters less than the directional shift: the era of treating digital infrastructure's environmental impact as an externality is ending.

If you're a business leader, the message is clear: the cost of digital operations will increasingly reflect their environmental footprint. That means factoring carbon intensity into cloud vendor selection, not just price and features. It means asking potential data center partners about their PUE scores and renewable energy percentages.

For cloud providers, the transition window is closing. Facilities that can't achieve competitive efficiency metrics will become financial liabilities. The smarter operators are already building with 2030 in mind, assuming carbon costs will be meaningfully higher than today.

Engineers and technologists should focus on skills around energy efficiency, renewable integration, and environmental impact measurement. As these concerns move from nice-to-have to business-critical, expertise in green infrastructure will command premium salaries.

Policy makers need to think carefully about implementation details. A poorly designed digital pollution tax could kneecap innovation, drive facilities to jurisdictions with lax rules, or simply get passed on to consumers as higher prices without changing behavior. The best designs create strong incentives for improvement while providing transition periods and support for companies making good-faith efforts to decarbonize.

For individuals, the implications are subtler but real. The free-flowing abundance of cloud services might get a bit more expensive. But that cost could drive efficiency improvements that make services better while using less energy. We've seen that pattern before with cars, appliances, and buildings, where environmental regulations sparked innovation that improved products beyond just emissions.

Here's what this is really about: Can we build a digital civilization that doesn't cook the planet?

For the past three decades, we've treated data centers like they exist in some ethereal cloud, disconnected from physical reality. Every search query, every video stream, every AI-generated image arrives instantaneously and invisibly, so we forgot about the sprawling industrial infrastructure making it possible.

Climate change is forcing us to remember. The computation revolution and the climate crisis are colliding, and something has to give. Either we radically reduce the environmental impact of digital infrastructure, or we accept that our digital ambitions will accelerate ecological collapse.

Digital pollution taxes are one tool for threading that needle. Not a perfect tool, not a complete solution, but a mechanism for making environmental costs visible and creating market pressure to innovate.

The tech optimists believe we can engineer our way out, that better cooling, more efficient chips, and abundant renewables will let us keep growing digital services without growing emissions. The skeptics think AI's appetite for computation will outrun every efficiency gain, leaving us with a stark choice between digital abundance and climate stability.

The truth probably lies somewhere in between. We can have both, but not by accident. It will require deliberate policy choices, aggressive investment in clean energy, and a willingness to pay the true cost of our digital lives.

Twenty years from now, we'll look back at today's data centers the way we now look at 1970s gas-guzzlers: inefficient dinosaurs from an era before we knew better. The question is whether we make that transition through market forces accelerated by smart policy, or through crisis-driven emergency measures after the damage is done.

The cloud isn't weightless. It's time we started treating it like the massive physical infrastructure it is, with all the environmental responsibility that implies. Digital pollution taxes might just be the wake-up call that forces us to build the future we claim to want: a digital civilization that actually lasts.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

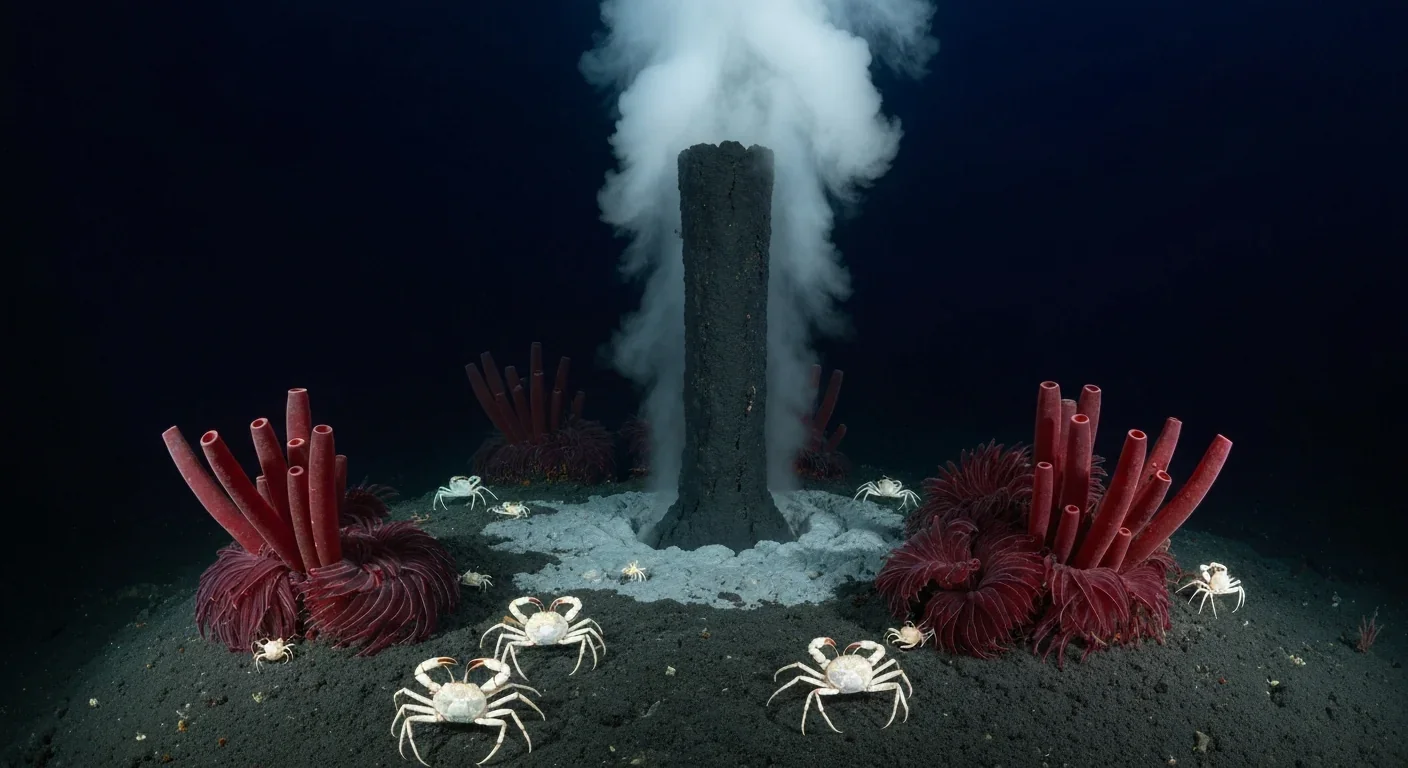

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

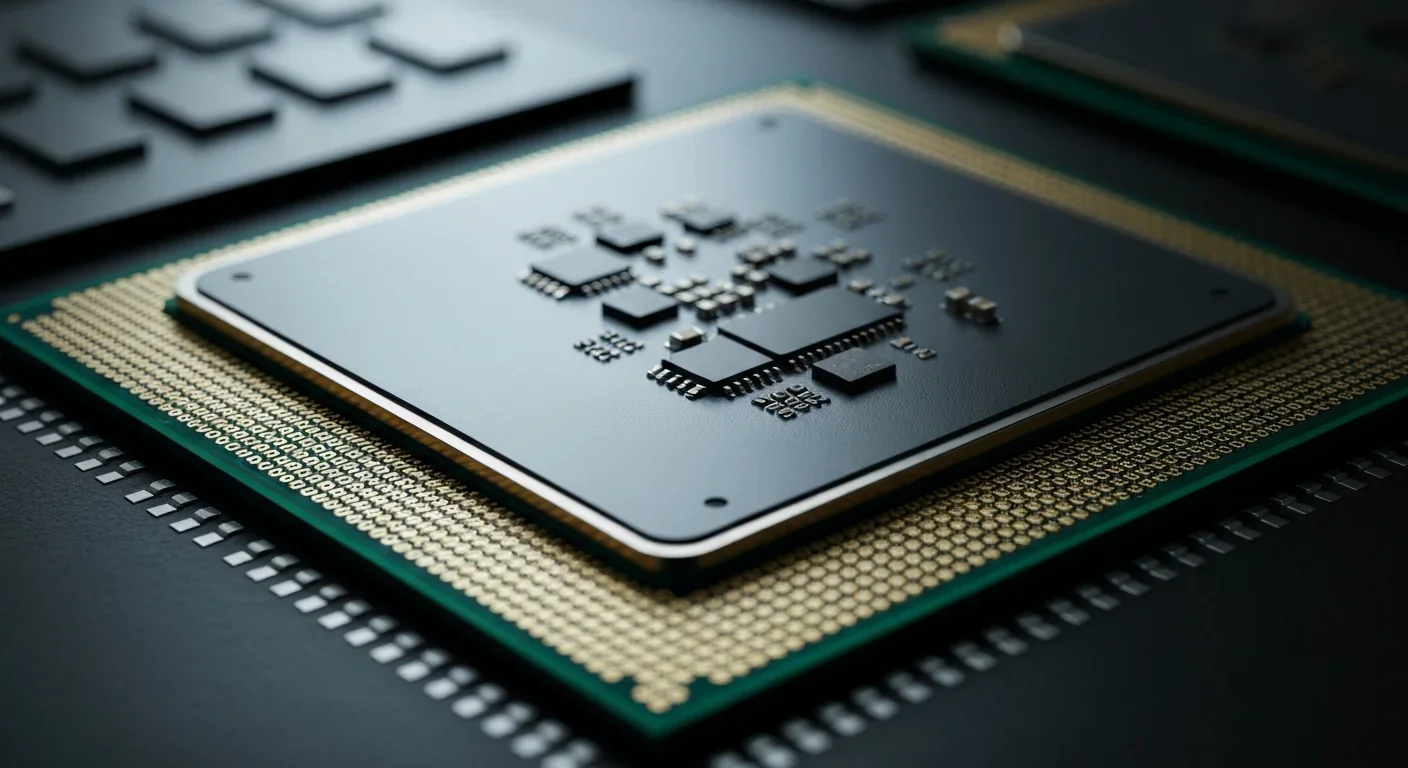

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.