AI Cameras Save Sea Turtles in Fishing Nets

TL;DR: Enzymatic recycling uses biological catalysts to selectively separate blended textiles into pure fibers, enabling infinite recycling without quality loss. Companies like Samsara Eco and Carbios are scaling the technology commercially, with major brands committing billions in supply agreements.

Somewhere in a facility in New South Wales, Australia, a batch of old nylon jackets is being dissolved not by harsh chemicals or intense heat, but by enzymes - microscopic biological machines that carefully snip apart polymer chains the way scissors cut thread. Within 48 hours, what was once a jacket becomes pure monomers, ready to be reassembled into virgin-quality fiber. This isn't a lab experiment anymore. It's happening at commercial scale, and it's about to change how the fashion industry thinks about waste.

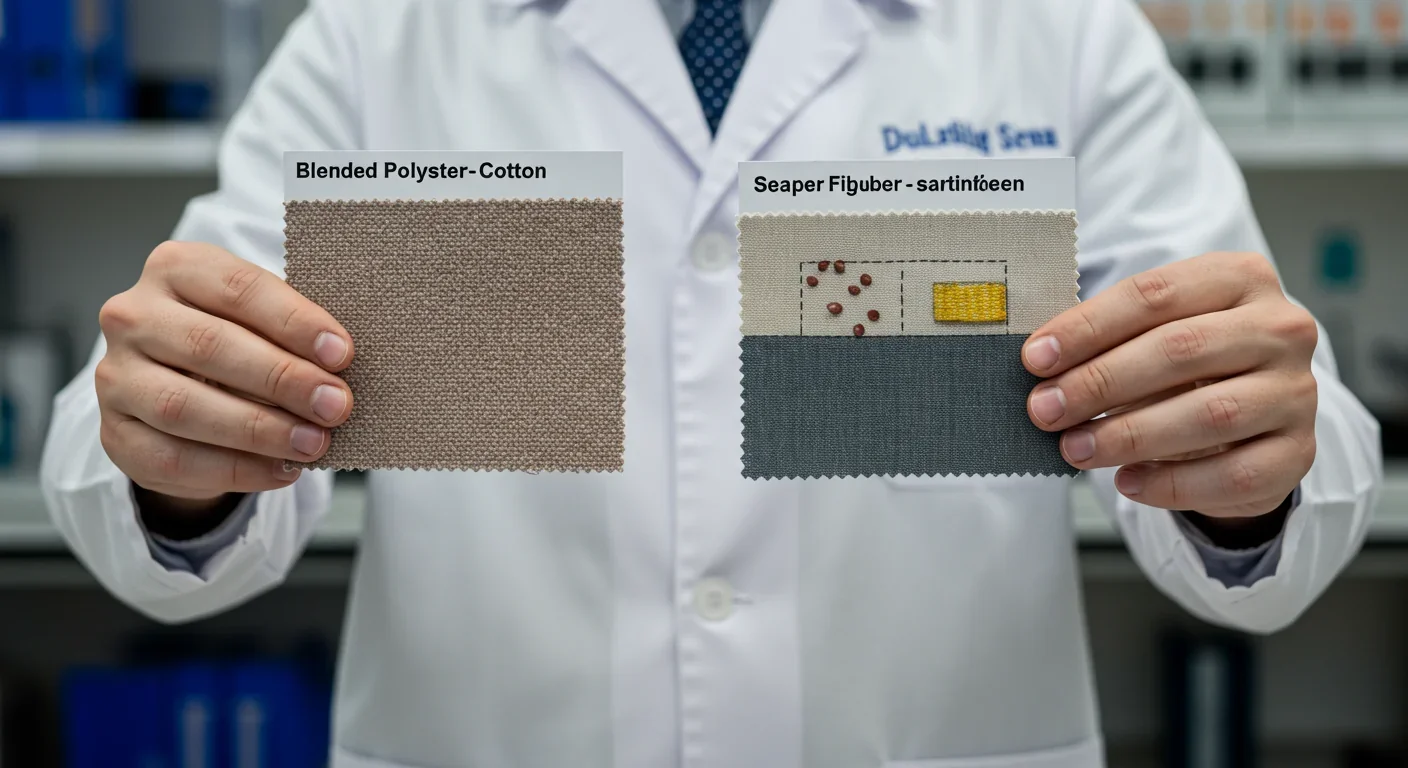

The global fashion industry produces over 92 million tons of textile waste every year, a figure projected to hit 134 million tons by 2030. Less than 1% of that material gets recycled back into new clothing. The reason? Most of our clothes are blends - cotton mixed with polyester, nylon woven with elastane - and conventional recycling can't separate them. Mechanical shredding downgrades fibers into filling material. Chemical processes require extreme temperatures and caustic solvents. But enzymes work differently. They're selective, breaking down specific polymers while leaving others untouched, and they operate under conditions mild enough to preserve fiber quality.

More than 60% of post-consumer textiles are now blended fabrics, according to Refashion's 2023 estimate. That polyester-cotton T-shirt you're wearing? Conventional recycling can't handle it. The fibers are too intimately mixed. Mechanical recycling shreds everything together, producing short, weak fibers suitable only for insulation or rags - what the industry calls "downcycling." You can't make new clothes from it.

Chemical recycling has made some progress, but it typically relies on harsh solvents or high-temperature depolymerization that consumes significant energy and can degrade fiber quality. According to research published in Sustainability, even advanced chemical recycling of polyester uses up to 12% of the energy required to make virgin fiber - still a massive improvement, but with environmental tradeoffs.

The textile industry has been stuck in a bind: fashion increasingly demands performance blends (moisture-wicking, stretch, durability), but those same blends create an end-of-life nightmare.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency estimates 11 million tons of textile waste hit American landfills annually. Globally, the fashion industry contributes 1.2 billion tons of CO₂ each year.

Enzymatic recycling offers a way out, because enzymes are exquisitely selective. A cellulase enzyme will attack cotton's cellulose structure but ignore polyester entirely. A PETase enzyme will cleave polyester's ester bonds while leaving nylon untouched. This selectivity makes it possible to disassemble a blended garment piece by piece, recovering each fiber type in usable form.

Enzymes are proteins that catalyze specific chemical reactions. In nature, they help organisms break down complex molecules for energy - think of how your stomach enzymes digest food. Scientists have adapted this process for textiles by identifying and engineering enzymes that target specific polymer bonds.

Here's how it works in practice, based on research from North Carolina State University published in Resources, Environment and Sustainability. Take a cotton-polyester blend. Researchers apply a "cocktail" of cellulase enzymes in a mildly acidic solution - about as acidic as vinegar - at 50°C, roughly the temperature of a hot washing machine. Over the course of 48 hours, the enzymes systematically chop up the cellulose in cotton, breaking it into glucose molecules. The polyester? Completely untouched. After washing away the glucose, what remains is clean polyester fiber ready for recycling.

"We can separate all of the cotton out of a cotton-polyester blend, meaning now we have clean polyester that can be recycled."

- Dr. Sonja Salmon, Associate Professor, NC State University

The process is remarkably gentle. "It's a mild process - the treatment is slightly acidic, like using vinegar - and we ran it at 50°C, which is like the temperature of a hot washing machine," Salmon explains.

But there's a twist. Real-world garments aren't just fiber. They're dyed, treated with wrinkle-resistant finishes, coated for water resistance. These chemical treatments can block enzyme access. Graduate researcher Jeannie Egan found that on fabrics treated with durable-press chemicals, enzyme degradation dropped below 10% without pre-treatment. "Without pre-treating it, we achieved less than 10% degradation, but after, with two enzyme doses, we were able to fully degrade it," she noted. This means commercial-scale enzymatic recycling needs to account for garment finishes - either through pre-treatment steps or higher enzyme concentrations.

The process also yields valuable byproducts. The glucose released when cotton breaks down can feed anaerobic digesters to produce biofuel. Cotton fragments that resist enzymatic breakdown can serve as reinforcing agents in paper or composite materials. Even the "waste" has value in a circular system.

For synthetic-synthetic blends like polyester-nylon, the approach is similar but uses different enzymes. Samsara Eco's EosEco™ technology, for instance, uses proprietary enzymes to break down nylon 6,6 and polyester into their constituent monomers - the molecular building blocks. These monomers are chemically identical to virgin materials, so fibers made from them have no quality loss. It's true circular recycling: infinite loops without degradation.

Some companies are even using AI to design novel enzymes. Samsara Eco employs artificial intelligence to model protein structures and predict which enzyme variants will most efficiently cleave specific polymer bonds. This accelerates development from years to months and allows for highly tailored enzymes that work on real-world textile waste, not just lab samples.

Enzymatic textile recycling has moved beyond pilot plants. Several companies are now operating or building commercial-scale facilities, with major fashion brands signing long-term supply contracts.

Samsara Eco is the current frontrunner. The Australian company has developed EosEco™, an enzymatic process that recycles nylon 6,6, nylon 6, polyester, and blended textiles. Unlike traditional recycling, which degrades fiber quality with each cycle, enzymatic recycling returns the polymer to monomers, enabling infinite recycling without quality loss. Samsara's facilities in Australia already enabled a sold-out Lululemon Anorak jacket line made from enzymatically recycled nylon.

In 2024, Lululemon signed a 10-year offtake agreement with Samsara, committing to purchase enzymatically recycled fibers by 2030. The partnership includes $100 million in funding and plans for the world's first nylon 6,6 enzymatic recycling facility in Southeast Asia, targeted to be operational by late 2026. According to Sarah Cook, Samsara's Chief Commercial Officer, "We're planning to build the world's first nylon 6,6 enzymatic recycling facility with NILIT Ltd. in Southeast Asia, which we're targeting to be operational by late 2026." The partnership aims to meet 30% of global nylon 6,6 demand.

Samsara is also opening a Commercial Innovation Hub in Jerrabomberra, New South Wales, in mid-2025, with plans for an international facility in 2028. CEO Paul Riley emphasizes the environmental advantage: "EosEco reduces the end-to-end recycling time, while also operating at a lower temperature and pressure to ultimately reduce waste and carbon emissions."

Carbios, a French biotech company, has focused on enzymatic depolymerization of PET polyester. While Carbios initially targeted plastic bottles, the company is now applying its enzyme technology to textile waste. The process breaks PET down to its original monomers (terephthalic acid and ethylene glycol), which can be repolymerized into virgin-quality polyester. Carbios is still in earlier stages of commercial scaling for textiles but has demonstrated the technology at pilot scale.

Eastman Chemical Company operates a molecular recycling plant in Kingsport, Tennessee, with capacity to process 110,000 metric tons of plastic waste annually, including polyester textiles. While Eastman's process is primarily chemical rather than purely enzymatic, the company is exploring hybrid approaches that combine enzymatic pre-treatment with chemical depolymerization to improve efficiency.

Syre, a textile-to-textile recycling company, uses a depolymerization process to produce BHET (Bis(2-Hydroxyethyl) terephthalate), an intermediate chemical that's then polymerized into PET. Syre claims its process reduces CO₂ emissions by up to 85% compared to oil-based virgin polyester. H&M has committed to a $600 million, seven-year offtake agreement with Syre, signaling strong brand confidence in advanced recycling technologies.

In Europe, enzymatic recycling capacity is projected at 50,000 tons per year according to Fraunhofer Umsicht data, a modest but growing share of the continent's overall chemical recycling infrastructure. This capacity represents enzymatic recycling's transition from research labs to industrial-scale deployment.

Meanwhile, researchers at the University of Amsterdam, in collaboration with Avantium, have developed a chemical hydrolysis process using superconcentrated hydrochloric acid (43% HCl) at room temperature to separate cotton from polyester. Published in Nature Communications, the process converts cotton into glucose suitable for bio-based plastics while leaving polyester intact for further recycling. Avantium tested the method in its Dawn pilot plant on actual post-consumer polycotton waste, achieving high glucose yields. Professor Gert-Jan Gruter notes, "Our techno-economic analysis looks rather favourable," positioning the technology for commercial scale-up. The glucose produced can feed Avantium's production of FDCA, a component in PEF polyester, creating a bio-based circular loop.

Reju, launched by former Adidas CEO Patrik Frisk, utilizes VolCat, an organic catalytic chemical recycling process for polyester textiles and packaging. The process extracts clean monomers while creating 50% less CO₂ compared to virgin polyester, according to the company.

The shift from pilot projects to commercial products is accelerating. Lululemon's sold-out Anorak jacket wasn't a publicity stunt - it was a market test that proved enzymatically recycled fibers meet high-performance standards for activewear. The jacket's success demonstrated that consumers can't tell the difference between virgin and enzymatically recycled nylon, a critical validation for scaling the technology.

Patagonia has partnered with multiple recycling innovators including Circ (cellulose recovery), Eastman (polyester recycling), and Aquafil (nylon regeneration) to integrate recycled fibers into new products. The outdoor brand's commitment to circularity has made it an early adopter and testing ground for emerging technologies.

H&M Group, one of the world's largest fashion retailers, has invested heavily in circular supply chains. Beyond the Syre offtake agreement, H&M has backed Ambercycle, a company developing enzymatic processes for polyester. These partnerships reflect a broader strategic shift: major brands are no longer treating recycled materials as niche or marketing gimmicks but as core supply chain components.

The circular fashion economy is valued at $7.63 billion in 2025 and projected to reach $18.42 billion by 2035 - growth driven by regulatory pressure, consumer demand, and economic benefits of securing stable, domestically sourced fiber supplies.

Enzymatic recycling is particularly attractive because it de-risks supply chains. Fashion brands dependent on virgin polyester are exposed to oil price volatility and geopolitical disruption. Enzymatic recycling allows them to create closed loops, sourcing feedstock from their own garment take-back programs. Lululemon's 10-year contract with Samsara guarantees fiber supply through 2030, insulating the brand from commodity market fluctuations.

The environmental case for enzymatic recycling is compelling but nuanced. Let's break down the comparisons.

Versus Mechanical Recycling: Mechanical recycling - shredding textiles and re-spinning fibers - has minimal energy requirements but severe quality limitations. Each recycling cycle shortens fibers, making them progressively weaker. After one or two cycles, mechanically recycled fibers are only suitable for non-woven applications like insulation. Enzymatic recycling, because it returns materials to monomers, avoids this degradation entirely. You can recycle the same material infinitely without quality loss.

Versus Chemical Recycling: Traditional chemical recycling uses high heat (200-300°C) and aggressive solvents to break down polymers. While effective, it's energy-intensive and can produce hazardous byproducts. Enzymatic processes operate at 50-80°C - temperatures achievable with low-grade industrial heat or even solar thermal systems. Syre's process, for example, claims an 85% CO₂ reduction compared to virgin polyester. Reju's VolCat process reports 50% lower emissions. Samsara's EosEco™ operates at lower temperature and pressure, reducing both energy consumption and carbon footprint.

Versus Virgin Production: Making virgin polyester from petroleum is energy-intensive and contributes to fossil fuel dependency. Even with conservative estimates, enzymatic recycling uses a fraction of the energy. The University of Amsterdam's acid hydrolysis process, while using concentrated HCl, operates at room temperature, avoiding the massive heat inputs of virgin fiber production.

There's also the waste reduction angle. Eleven million tons of textile waste enter U.S. landfills annually. Globally, the fashion industry's 92 million tons of waste represents an enormous squandering of embedded resources - water, energy, raw materials. Enzymatic recycling transforms that waste into feedstock, closing the loop.

But enzymatic processes aren't zero-impact. Enzyme production itself requires fermentation facilities, often using genetically modified microorganisms to produce enzymes at scale. Some critics raise concerns about GMO use, though enzymes are proteins that denature (break down) after use and don't persist in the environment. There are also questions about energy inputs for enzyme production and the infrastructure needed to collect, sort, and pre-treat garments.

The net environmental benefit depends heavily on scale and system design. A recent study in Sustainability noted that enzymatic recycling processes may struggle economically during scale-up due to low concentrations of desired outputs after fermentation, meaning higher volumes and energy may be needed to achieve commercial viability. These are solvable engineering challenges, not fundamental barriers, but they matter for near-term deployment.

Enzymatic textile recycling works in the lab and at pilot scale. Scaling to millions of tons per year? That's where the hard problems emerge.

Feedstock Sorting and Preparation: Enzymes are selective, but they need to know what they're digesting. A bale of mixed textile waste containing cotton-polyester, nylon-spandex, wool-acrylic, and pure cotton garments requires sophisticated sorting. Near-infrared spectroscopy and AI-powered sorting systems are advancing rapidly - companies like Tomra have developed automated textile sorters - but the infrastructure isn't yet widespread.

"The large variety in materials means robust sorting is required to enable advanced recycling processes with maximum recovery and value."

- Dr. Thilo Becker, Senior Solution Manager, Tomra

Garment Finishes and Contaminants: As NC State's research showed, dyes and durable-press chemicals can inhibit enzyme access. Real-world garments also contain zippers, buttons, labels, and adhesives. Pre-treatment to remove contaminants or chemical pre-processing to improve enzyme accessibility adds cost and complexity. Some facilities may need to develop multi-stage processes: mechanical disassembly, chemical pre-treatment, enzymatic digestion, then separation and purification.

Enzyme Cost and Production: Enzymes are biological catalysts, meaning they're not consumed in the reaction - one enzyme molecule can break thousands of bonds. But producing enzymes at industrial scale requires fermentation facilities and purification systems. Enzyme cost has dropped dramatically over the past decade (thanks largely to advances in industrial biotechnology for biofuels), but it's still a significant operating expense. Companies are investing in enzyme engineering to improve activity (how fast they work) and stability (how long they last), both of which reduce costs.

Economic Viability: Enzymatically recycled fibers must compete with virgin materials on price and quality. Virgin polyester is cheap because it benefits from decades of optimization and economies of scale. Oil price crashes can make virgin fiber temporarily cheaper than any recycled alternative. For enzymatic recycling to reach true scale, it needs regulatory support (mandates for recycled content, landfill taxes, extended producer responsibility), brand commitments (long-term offtake agreements like Lululemon's), and consumer willingness to pay for sustainability.

The techno-economic analysis for Avantium's Dawn process looks "rather favourable," according to Professor Gruter, but that assessment is based on pilot data. Scaling from 1 ton per day to 100 tons per day often reveals unforeseen challenges - equipment wear, process variability, logistics bottlenecks.

Infrastructure and Investment: Building enzymatic recycling facilities requires significant capital. Samsara's $100 million funding round is substantial, but it's just one company. Reaching the scale needed to process even 10% of global textile waste would require billions in investment across collection, sorting, processing, and remanufacturing infrastructure. That investment is starting to flow - H&M's $600 million Syre deal, Lululemon's Samsara partnership, Patagonia's multi-company collaborations - but it's early days.

Regulatory and Standardization Gaps: There's no global standard for "enzymatically recycled" fiber. What quality metrics apply? How is it certified? What disclosure is required? The lack of standardization makes it difficult for brands to compare suppliers and for consumers to make informed choices. Industry groups are working on frameworks, but progress is slow.

Despite these challenges, momentum is building. The European Union's Circular Economy Action Plan and upcoming Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation will mandate higher recycled content and recyclability standards, creating strong incentives for enzymatic recycling. In the U.S., states like California are considering extended producer responsibility legislation for textiles. These policies will level the playing field, making recycled fibers more economically competitive.

Imagine a world where garment tags include a recycling code as clear as the ones on plastic bottles. You drop your worn-out jacket at a collection point, where it's scanned, sorted by fiber type, and routed to the appropriate recycling facility. Within weeks, the nylon is broken down to monomers, purified, and repolymerized into new fiber. A few months later, that same material is back on the rack as a new jacket - chemically identical to virgin, with zero quality loss.

That's the vision driving enzymatic recycling, and it's closer than you might think.

Samsara's 2026 Southeast Asia facility will process nylon 6,6 at commercial scale, supplying Lululemon and potentially other brands. If it hits its target of 30% of global nylon 6,6 demand, it will fundamentally reshape the synthetic fiber market. Other companies will follow. Carbios, Eastman, Syre, Reju - each is betting that enzymatic and advanced chemical recycling will become the industry standard.

The next five years will be critical. We'll see whether the technology can scale economically, whether collection and sorting infrastructure can keep pace, and whether brands and consumers commit to the circular model. Early signs are promising. The sold-out Lululemon jacket proved market demand. The $600 million H&M deal proved investor confidence. The EU regulations prove political will.

But challenges remain. We need better enzyme engineering to handle diverse garment finishes. We need automated sorting systems deployed at scale. We need harmonized standards so "recycled" means something consistent. And we need policy frameworks that make recycling economically rational, not just environmentally virtuous.

There's also a question of scope. Enzymatic recycling handles synthetic and cellulosic blends beautifully, but what about wool-synthetic blends? Silk-polyester? Leather alternatives? Each material combination may require tailored enzymes or hybrid processes. The research is ongoing - scientists are exploring enzymes for nylon, for elastane, for acrylic - but we're not there yet.

The circular fashion economy is projected to nearly triple in value over the next decade. That growth will be powered by technologies like enzymatic recycling, but also by changes in design (making clothes easier to disassemble), business models (rental and resale), and consumer behavior (buying less, choosing quality, repairing more).

Enzymatic recycling won't solve fashion's sustainability crisis alone. The industry still overproduces, still relies on exploitative labor, still markets disposability. But it's a crucial piece of the puzzle - a way to close the loop on materials, reduce waste, and break the dependency on virgin resources.

"Continuous collaboration across the entire textile value chain - manufacturers, brands, recyclers, and policymakers - is essential to achieve a truly circular system."

- Dr. Thilo Becker, Tomra

No single technology, company, or policy will get us there. It takes an ecosystem.

Within the next five years, you'll likely own clothing made from enzymatically recycled fibers, whether you know it or not. Major brands are already integrating these materials into their supply chains. The jacket you buy in 2027 might contain nylon from Samsara's Southeast Asia plant, polyester from Syre's depolymerization process, or cellulose from Avantium's glucose-to-fiber loop.

As a consumer, you can accelerate this transition by supporting brands that commit to circular practices, participating in garment take-back programs, and pushing for stronger recycling regulations. The technology exists. The business models are emerging. What's needed now is demand - from shoppers, from investors, from voters - for a fashion industry that doesn't treat clothing as disposable.

The enzymes are already working, quietly dismantling yesterday's waste into tomorrow's wardrobe. The question isn't whether circular fashion is possible - it's how fast we can scale it.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.