3D-Printed Coral Reefs: Can We Engineer Marine Recovery?

TL;DR: Abandoned fishing nets kill marine life for decades, but AI drones, grassroots cleanups, and international policy are turning the tide on ocean's deadliest pollution.

Right now, while you read this, tens of thousands of fishing nets are silently strangling marine life across the planet's oceans. They're not attached to boats. Nobody's coming back for them. They're just out there, drifting through the water column like invisible death traps, killing everything they touch. Scientists call them "ghost gear," and they've become the ocean's most lethal form of pollution - surpassing even the notorious plastic bags and straws that dominate environmental headlines.

Here's what makes ghost gear uniquely terrifying: unlike most marine debris that eventually sinks or washes ashore, abandoned fishing nets keep doing exactly what they were designed to do. They catch fish. They entangle turtles. They snare dolphins and seals. And because modern fishing gear is built from synthetic materials designed to last decades, these nets can continue their grim work for generations. In the Florida Keys alone, scientists estimate over a million abandoned lobster and crab pots litter the seafloor, with 85,000 actively "ghost fishing" right now.

The scale is staggering. More than 60% of the surface debris in the North Pacific Gyre - that infamous garbage patch twice the size of Texas - is fishing-related equipment when measured by weight. We're not talking about scattered beer cans or plastic bottles. We're talking about industrial-scale fishing apparatus, abandoned either through storms, accidents, or simple economic calculus when retrieval costs more than replacement.

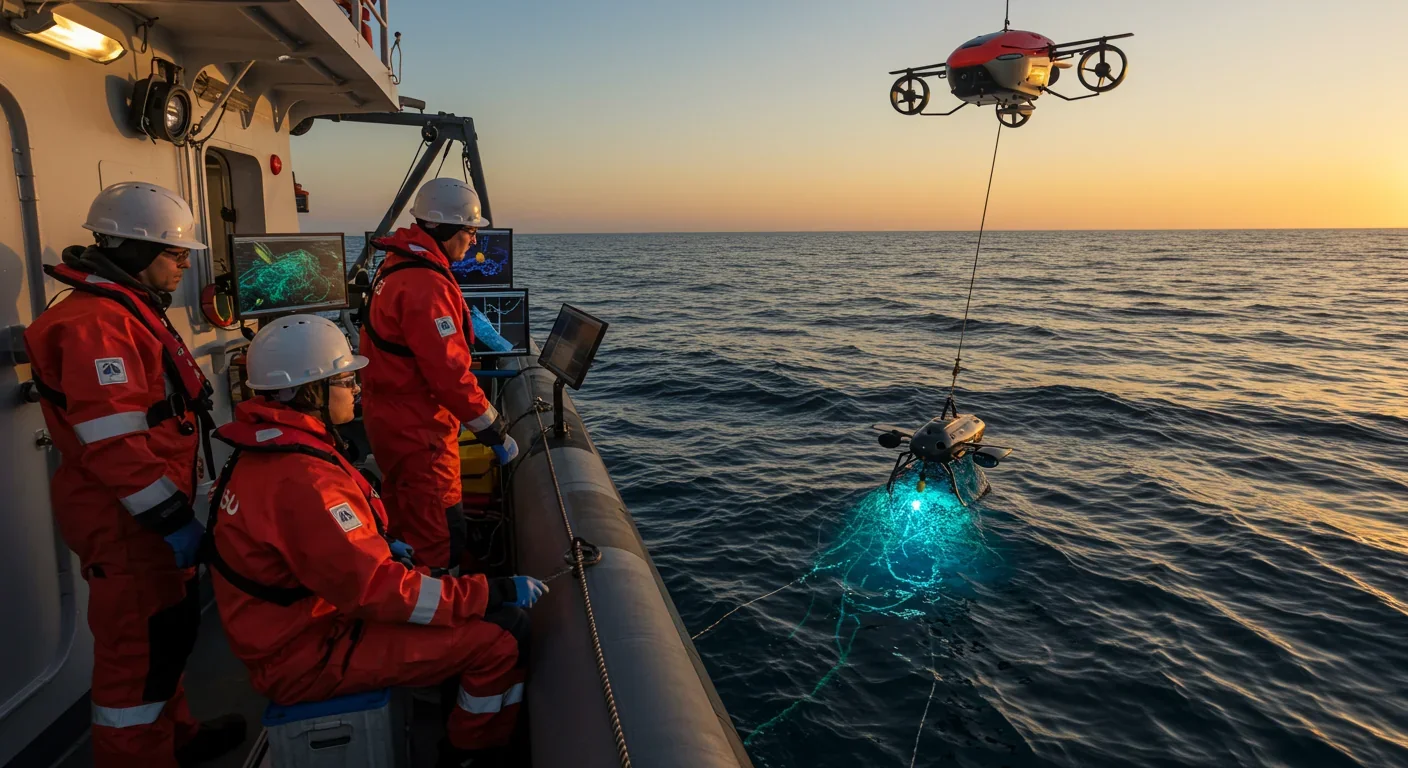

But here's the twist: this nightmare scenario has sparked one of the most innovative and collaborative conservation movements of our time. From AI-powered drones mapping ghost nets along remote coastlines to grassroots diving teams pulling traps from coral reefs, a global network of scientists, fishermen, tech innovators, and conservationists is waging an increasingly effective war against the ocean's silent killers.

Ghost gear doesn't just kill individual animals - it reshapes entire ecosystems. When 45% of marine mammals listed on the International Union for Conservation of Nature's Red List have been negatively affected by abandoned fishing equipment, we're witnessing a systematic threat to biodiversity that rivals climate change in its immediacy.

The mechanics of ghost fishing create a perverse feedback loop. A lost net catches fish. Those trapped fish attract predators. The predators become entangled. Their decomposing bodies attract scavengers. The cycle continues, sometimes for decades, with a single net potentially killing thousands of animals before it finally biodegrades - a process that can take up to 600 years for some synthetic materials.

Research from the International Seafood Sustainability Foundation reveals that ghost gear particularly devastates sea turtle populations. These ancient mariners, already struggling with habitat loss and climate change, face entanglement rates that make survival to reproductive age increasingly improbable. In some regions, ghost nets account for more turtle deaths than all other human activities combined.

The economic toll matches the ecological damage. Globally, an estimated 90% of species caught in lost gear are commercially valuable, and some fish stocks experience up to a 30% decline due to ghost fishing. This isn't just an environmental problem - it's actively undermining the livelihoods of fishing communities worldwide. Fishermen compete against their own abandoned equipment for increasingly scarce resources.

Even coral reefs, already stressed by warming oceans and acidification, face additional pressure from ghost gear. Nets draped across reef structures block sunlight, smother polyps, and create abrasion zones where constant wave action grinds synthetic fibers against living coral. A single abandoned net can devastate hundreds of square meters of reef habitat, destroying in hours what took centuries to build.

The fight against ghost gear has entered a new era, powered by technologies that would have seemed like science fiction a decade ago. In Australia's Northern Territory, researchers deployed drones equipped with specialized cameras to scan vast stretches of remote coastline. The results were both alarming and encouraging: they identified ghost nets at a rate of approximately one per kilometer of coast - far higher than previous ground surveys suggested. But crucially, they now know where to look.

The WWF Baltic has taken detection a step further, combining drone imagery with machine learning algorithms that can distinguish abandoned nets from natural kelp forests and other underwater features. This AI-assisted approach has increased detection rates by 300% compared to traditional survey methods, transforming what was once a needle-in-haystack problem into a targeted removal operation.

In Scotland, scientists are testing acoustic tracking systems that could revolutionize prevention. By attaching small, biodegradable acoustic tags to fishing gear, they can track equipment in real-time and locate it if lost. The tags cost less than $5 each - a fraction of the gear's value - and the system has already helped recover equipment that would otherwise have become ghost gear.

Mobile apps are turning citizen observers into a distributed early-warning system. The Responsible Seafood Advocate reports that platforms like "Ghost Fishing Spotter" allow recreational divers, sailors, and coastal residents to report sightings with GPS coordinates and photos. These crowdsourced databases have identified thousands of previously unknown ghost gear sites, many in marine protected areas where removal is now prioritized.

Perhaps most promising are the "smart floats" being developed in Norway - self-deploying buoys that use satellite connectivity and GPS to mark lost fishing gear locations automatically. When a trawl net or longline separates from its vessel, the float activates, transmitting coordinates directly to recovery teams. Early trials show an 80% recovery rate for marked gear, compared to less than 5% for traditional equipment.

While technology provides the tools, human determination drives the actual cleanup. The Northwest Straits Foundation has removed over 5,000 derelict fishing nets from Washington State waters since 2002, preventing an estimated 1.5 million pounds of bycatch. Their model combines volunteer divers, commercial salvage expertise, and local fishing community partnerships - a blueprint now replicated worldwide.

In Thailand, underwater citizen science initiatives trained recreational divers to document and, when safe, remove small ghost gear items during regular dives. This distributed approach doesn't just clean reefs - it creates tens of thousands of ocean advocates who understand the problem viscerally, having witnessed the carnage firsthand.

The Center for Coastal Studies concluded their 2025 recovery season by removing 47 tons of abandoned fishing gear from Massachusetts waters. Their team includes former commercial fishermen who bring invaluable knowledge about where gear tends to accumulate and how to extract it without causing additional habitat damage.

Organizations like Healthy Seas have pioneered a circular economy model: recovered ghost nets are cleaned, processed, and recycled into new products, including fishing gear, carpets, and activewear. This economic incentive transforms ghost gear from worthless ocean debris into a valuable resource, creating jobs in coastal communities while solving an environmental crisis.

The Olive Ridley Project focuses specifically on protecting sea turtles in the Indian Ocean. Their combination of emergency rescue operations, ghost gear removal, and fisherman education programs has documented over 1,000 turtle rescues from abandoned fishing equipment. More importantly, they've established partnerships with local fishing communities to prevent gear loss in the first place.

Individual cleanups matter, but systemic change requires policy frameworks that address root causes. The Global Ghost Gear Initiative (GGGI), launched in 2015, has grown to include 18 member governments and more than 120 organizations. It's become the primary international clearinghouse for best practices, standardized reporting, and coordinated action plans.

The GGGI model focuses on four pillars: building evidence about ghost gear impacts, identifying solutions for both prevention and removal, scaling proven interventions, and establishing enabling policy frameworks. This isn't just talk - member nations have committed to concrete targets, including mandatory gear marking, lost-gear reporting requirements, and penalties for non-compliance.

The International Seafood Sustainability Foundation published comprehensive guidelines in 2025 for developing national Plans of Action on managing abandoned, lost, and discarded fishing gear. These frameworks help countries move from awareness to implementation, with measurable milestones and accountability mechanisms.

Vessel tracking technology, promoted by organizations like Global Fishing Watch, is becoming mandatory in many jurisdictions. By monitoring fishing vessel movements and catch locations in real-time, authorities can correlate lost gear reports with specific vessels, creating economic incentives for better gear stewardship.

Some regions are experimenting with "gear libraries" where fishermen lease rather than own equipment. This model, similar to tool libraries in urban communities, ensures professional maintenance, encourages gear recovery, and reduces the economic pressure that sometimes makes abandoning damaged equipment seem rational.

Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) schemes are gaining traction, making fishing gear manufacturers and importers financially responsible for end-of-life management. Norway's program, which includes a small fee on new gear purchases to fund recovery operations, has achieved recovery rates exceeding 90% for tagged equipment.

The economic costs of marine pollution extend far beyond dead fish and damaged nets. The IUCN estimates that plastic pollution, including ghost gear, costs the global economy at least $2.5 trillion annually through impacts on fisheries, tourism, coastal communities, and human health.

Small-scale fishing communities bear a disproportionate burden. When ghost gear depletes local fish stocks, it's not corporate fishing companies that suffer most - it's families dependent on daily catches for both income and protein. In developing nations along the equator, where alternatives are scarce, ghost gear effectively steals food from the poorest populations.

Tourism-dependent economies face different but equally serious impacts. Who wants to snorkel in a reef festooned with abandoned nets? The Marine Biodiversity Science Center documents how Marine Protected Areas struggle to attract visitors when iconic species like sea turtles and dolphins are regularly found entangled and dying.

Yet the economics also reveal opportunities. The ghost gear recovery industry now employs thousands of people globally. From specialized salvage operators to recycling facility workers to gear-marking technology companies, solving this crisis is creating a blue economy that builds wealth while restoring ocean health.

The scale of the ghost gear crisis can feel overwhelming, but individual actions aggregate into systemic change. Here's what actually moves the needle:

Support organizations doing recovery work. Groups like the Ocean Conservancy, Healthy Seas, and the Olive Ridley Project operate on surprisingly small budgets. A $50 donation can fund removal of several derelict traps or nets.

Choose seafood from certified sustainable sources. Look for Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) or Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC) certifications. These programs require gear marking, loss reporting, and recovery protocols. Your purchasing decisions create market incentives for better practices.

Get involved locally. Coastal cleanup events often encounter ghost gear. Organizations like the Northwest Straits Foundation train volunteers for safe removal. Even if you don't dive, documenting locations helps professional teams prioritize operations.

Advocate for stronger policies. Contact elected representatives to support mandatory gear marking, lost-gear reporting requirements, and funding for recovery programs. The GGGI provides policy templates that work - officials need to hear that constituents care.

Spread awareness. Ghost gear doesn't have the visceral impact of an oil spill or the photogenic appeal of a polar bear on melting ice. Most people have never heard of it. Sharing information transforms invisible problems into political priorities.

Consider citizen science. Apps like Ghost Fishing Spotter turn your observations into actionable data. If you boat, fish, dive, or simply walk beaches, you're potentially a valuable contributor to mapping and removal efforts.

The ghost gear crisis represents a peculiar form of environmental damage: it's almost entirely solvable with existing technology and proven methods. Unlike climate change, which requires transforming global energy systems, or ocean acidification, which demands atmospheric chemistry changes, ghost gear just needs to be found and removed. The tools exist. The methods work. What's required is sustained commitment and resources - both achievable through collective action.

By 2030, if current trends continue, we could see ghost gear recovery rates exceed new abandonment rates for the first time in industrial fishing history. That tipping point, where the ocean actually gets cleaner year over year, is within reach. It requires scaling proven interventions, implementing mandatory gear marking globally, and maintaining funding for recovery operations.

The next generation of fishing technology promises inherent solutions: biodegradable nets that harmlessly decompose if lost, smart gear with mandatory tracking, and equipment designed for easy recovery rather than abandonment. Some of these technologies already exist and need only market adoption and regulatory support to become industry standard.

Marine Protected Areas are expanding globally, and many now include dedicated ghost gear removal as part of their management plans. The Marine Biodiversity Science Center documents how MPAs with active removal programs show measurable biodiversity recovery within just a few years - proof that interventions work when adequately resourced.

The climate connection adds urgency: ghost gear doesn't just kill wildlife, it interferes with the ocean's capacity to sequester carbon. Healthy fish populations and intact coral reefs are critical carbon sinks. Research from Bow Seat demonstrates that ghost gear disrupts these natural climate solutions, making ocean cleanup a climate action multiplier.

Perhaps most importantly, the ghost gear fight has created unprecedented collaboration between groups that historically viewed each other with suspicion. Commercial fishermen work alongside environmental activists. Tech companies partner with grassroots diving organizations. Governments coordinate with NGOs. This coalition-building offers a template for addressing other complex environmental challenges.

The ocean's silent killers are being hunted down, one net at a time, by a growing army of innovators, activists, scientists, and reformed industries. They're not waiting for perfect solutions or complete funding. They're out there now, in research vessels and fishing boats and diving gear, pulling death traps from the water and preventing new ones from being lost. It's working. The question isn't whether we can solve the ghost gear crisis - it's whether we'll commit the resources to do it before another generation of marine life pays the price for our industrial fishing legacy.

Every recovered net represents hundreds of animals that won't die slow, terrible deaths. Every prevented loss means fish stocks that can rebuild. Every community that joins the effort creates ripple effects that extend far beyond cleaned coastlines. The ocean's ghosts are being exorcised, but the job's not finished. Not even close. And that's exactly why it matters that you now know they exist.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

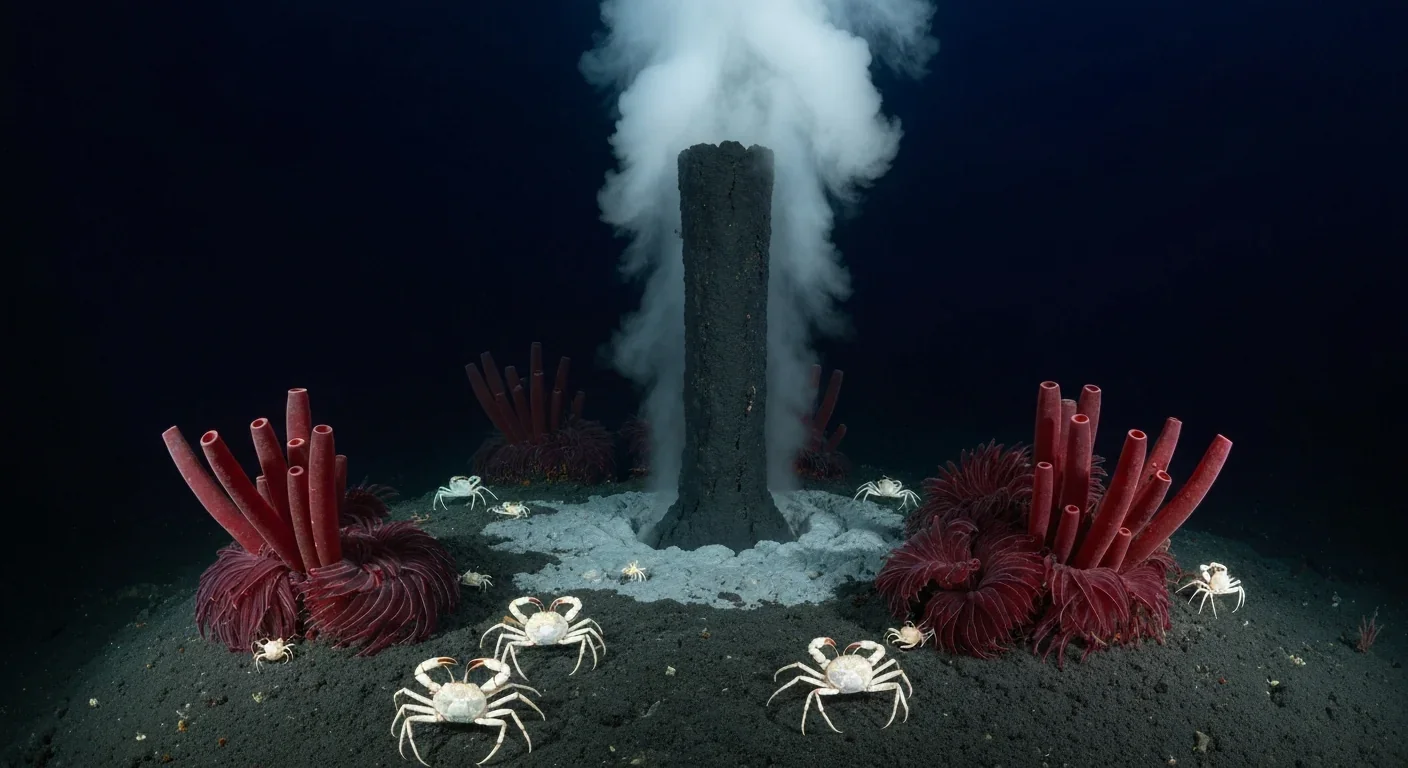

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

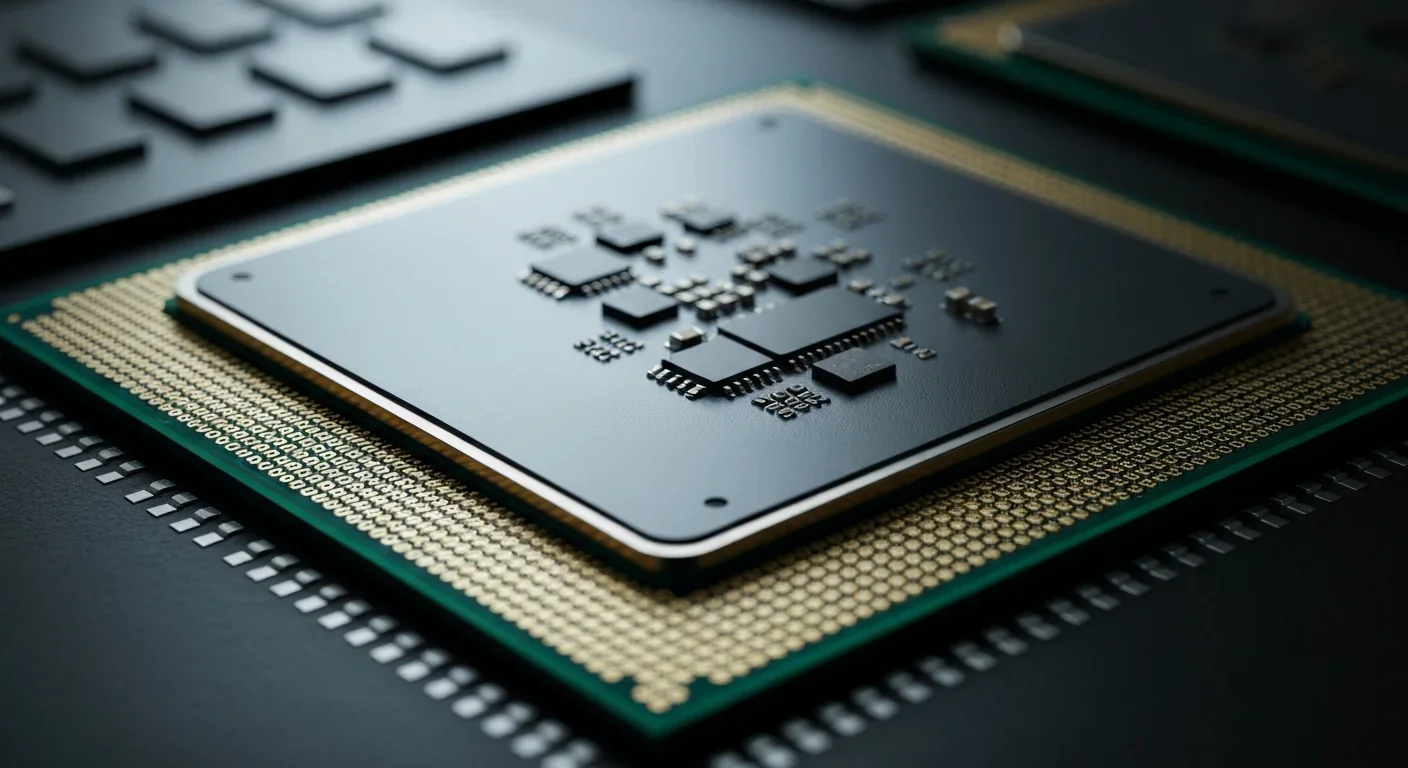

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.