AI Cameras Save Sea Turtles in Fishing Nets

TL;DR: Humanity extracts 50 billion tonnes of sand annually, making it the world's second-most consumed resource after water. This investigation reveals how unregulated mining is erasing islands, fueling violent black markets, and threatening coastal ecosystems while viable alternatives remain underutilized.

Every year, humanity consumes enough sand to build a wall 27 meters high and 27 meters wide around the entire equator. We're extracting 50 billion tonnes annually, making sand the second-most consumed natural resource on Earth after water. Yet this abundance is an illusion. The sand crisis isn't coming - it's already here, erasing islands from maps, fueling violent criminal networks, and threatening the concrete foundation of modern civilization.

The contradiction seems absurd. How can we be running out of something that covers deserts and beaches? The answer reveals a blind spot in how we think about resources: not all sand is created equal, and we're depleting the useful kind faster than geological processes can replenish it.

Sand might seem interchangeable, but construction-grade material requires specific properties that most sand lacks. River and marine sand grains are angular and rough, formed through centuries of geological weathering. These irregular surfaces create the binding strength needed for concrete and glass.

Desert sand, by contrast, is useless for construction. Wind erosion rounds the grains into smooth, polished spheres that cannot bond effectively in concrete mixtures. This is why Saudi Arabia, despite sitting atop vast desert dunes, imports sand from Australia for its building projects.

Not all sand is created equal. Desert sand is too smooth for construction, forcing even sand-rich nations to import the angular varieties needed for concrete.

The distinction matters because 75-80% of concrete is sand. Every kilometer of highway needs approximately 30,000 tonnes. An average house requires 200 tonnes of sand. When you consider that China used more concrete between 2011 and 2013 than the United States consumed during the entire 20th century, the scale becomes clear.

Global demand is projected to double by 2060, driven by urbanization in Asia and Africa. The natural sand market is expected to reach 2,233 million tonnes worth $114.9 billion by 2030, expanding at just 1.0% CAGR - far slower than consumption rates.

We're facing a geological speed limit. Rivers and oceans create construction-grade sand over millennia through erosion and weathering. Human extraction operates on quarterly earnings cycles. The mismatch is creating a resource crisis that rivals anything involving oil or rare earth minerals.

The modern sand crisis traces back to the post-World War II construction boom. As economies rebuilt and populations urbanized, concrete became civilization's default material. Unlike wood or stone, which require skilled labor, concrete democratized construction. Pour it into a mold, wait for it to harden, and you have a building.

This accessibility triggered exponential growth. Global concrete production increased from roughly 133 million cubic meters in 1950 to over 4 billion cubic meters today. Each cubic meter requires approximately 1,500 kilograms of sand.

Three historical forces converged to accelerate consumption:

Infrastructure megaprojects became national symbols of development. China's construction spree during its economic boom created demand that emptied riverbeds across Southeast Asia. India's highway expansion program, aiming to connect every village with paved roads, requires sand volumes that exceed sustainable extraction rates.

Land reclamation emerged as a solution for space-constrained nations. Singapore has imported over 517 million tonnes of sand since 1990, literally expanding its territory by 25%. The city-state's appetite created such demand that neighboring countries banned exports, triggering a regional crisis documented in Harvard Design Magazine.

Urbanization patterns shifted billions of people from rural areas to cities requiring massive infrastructure. The United Nations estimates that by 2050, 68% of humanity will live in urban areas, each requiring roads, buildings, and utilities - all made possible by sand.

"Every major technological transition creates resource bottlenecks we fail to anticipate. Now the concrete age is hitting geological limits."

- Resource Economics Analysts

The lesson from history is clear: every major technological transition creates resource bottlenecks we fail to anticipate. The Industrial Revolution depleted forests for charcoal. The automotive age created oil dependency. The digital economy spawned rare earth scarcity. Now the concrete age is hitting geological limits.

The consequences of unsustainable extraction are no longer theoretical. They're reshaping coastlines, destroying ecosystems, and destabilizing communities.

River sand extraction has become the second-most widespread human activity in coastal areas after fishing. In India, unregulated mining has caused entire river islands to disappear. The environmental damage cascades:

Riverbeds deepen when sand is removed, lowering water tables and threatening water supplies for agriculture and drinking. In Kerala, India, sand mining has lowered groundwater levels so dramatically that wells in nearby villages have run dry.

Bridge foundations become exposed as the riverbed drops, creating structural risks. Dozens of bridges in India have collapsed or been condemned after sand extraction undermined their supports.

Ecosystems collapse when sediment dynamics change. Fish species that depend on specific riverbed conditions disappear. Migratory birds lose nesting sites. The biodiversity impacts extend hundreds of kilometers downstream as altered sediment flows disrupt marine habitats.

As river sources dry up, extraction has moved offshore. The UN estimates that marine sand mining exceeds 6 billion tonnes annually, often in poorly regulated waters.

Recent research from Stanford's Center for Ocean Solutions found that sand dredging encroaches on marine protected areas, violating conservation boundaries with impunity. The rising tide of sand mining poses a growing threat to marine life through habitat destruction and sediment plumes.

Ocean mining creates underwater deserts. Dredging equipment scrapes the seafloor, destroying coral formations, seagrass beds, and the organisms that depend on them. Greenpeace reports that sediment clouds from mining operations can smother marine life across areas spanning hundreds of square kilometers.

Between 2005 and 2020, at least 24 Indonesian islands vanished entirely due to sand extraction - literally erasing territory from maps.

The most dramatic evidence comes from Southeast Asia, where sand smuggling has erased dozens of Indonesian islands from official maps. Singapore's insatiable demand created a black market that literally dismantled neighboring nations' territory, grain by grain.

Indonesia eventually banned sand exports, but illegal operations continued. Smugglers would anchor fleets of ships near uninhabited islands, pump the sand aboard, and disappear before authorities arrived. Between 2005 and 2020, at least 24 Indonesian islands vanished entirely.

The geopolitical implications extend beyond environmental damage. When islands disappear, so do maritime boundaries and exclusive economic zones. Nations lose territorial claims, fishing rights, and resource access - all for sand worth a few dollars per tonne.

When demand outstrips legal supply, organized crime fills the gap. The sand mafia phenomenon rivals drug trafficking in violence and corruption in parts of Asia.

In India, illegal sand mining operations kill dozens of people annually through both accidents and violence. Journalists investigating sand theft have been murdered. Government inspectors face death threats. Local communities challenging illegal extraction risk reprisals.

The economics are straightforward. River sand that costs $3-5 per tonne to extract legally sells for $15-30 in urban markets. Profit margins comparable to narcotics, with far lower enforcement risk, attract sophisticated criminal networks.

China's experience illustrates the enforcement challenge. When the government imposed stricter regulations on river sand extraction, prices increased by 600% almost overnight. The price spike created enormous black market incentives while legal sources couldn't meet demand.

"The regulatory framework remains inadequate globally. Most nations lack comprehensive sand mining laws, creating enforcement gaps that criminal networks exploit."

- Legal Framework Analysis, 2025

The regulatory framework remains inadequate globally. A 2025 analysis of legal frameworks found that most nations lack comprehensive sand mining laws. Jurisdictional disputes between federal, state, and local authorities create enforcement gaps that criminal networks exploit.

Indonesia's predicament demonstrates the international dimension. Despite export bans, illegal sand smuggling continues because neighboring countries need the resource and pay premium prices. Border enforcement across thousands of islands is nearly impossible.

The violence extends beyond human casualties. In many communities, sand mining destroys livelihoods. Fishing communities lose access to traditional waters as dredging operations take over. Cultural sites along riverbanks disappear into extraction pits. The social fabric tears as outside interests override local needs.

The extraction crisis intersects with climate change in ways that accelerate both problems. As sea levels rise, beaches provide natural barriers against storm surges and coastal flooding. But sand mining is destroying this defense precisely when we need it most.

Beaches exist in dynamic equilibrium. Rivers deliver sediment to the coast, ocean currents distribute it, and waves shape it into beaches. When upstream sand extraction depletes river sediment, beaches starve. When offshore dredging removes sand, coastal erosion accelerates.

The feedback loops are vicious. Coastal erosion threatens infrastructure, creating demand for concrete seawalls and land reclamation projects, which require more sand extraction, which accelerates erosion. We're trapped in a cycle where the solution to sand scarcity creates conditions demanding more sand.

Vietnam provides a case study in cascading failure. Extensive sand mining in the Mekong Delta has contributed to coastal erosion rates exceeding 50 meters per year in some areas. Communities that existed for generations have been abandoned as the sea reclaims the land.

The crisis demands urgent innovation across multiple fronts. Fortunately, alternatives are emerging that could reduce dependence on natural sand.

Manufactured sand (M-sand) is created by crushing quarried rock into construction-grade particles. The process involves crushing to create angular grains, washing to remove impurities, and grading to separate size fractions.

M-sand adoption has accelerated in regions facing natural sand shortages. India's construction sector has increasingly embraced manufactured alternatives as river sand becomes scarce and expensive. The material costs 30-40% less than natural sand in many markets while meeting construction standards.

However, manufacturing sand requires significant energy. Rock crushing operations consume electricity and generate carbon emissions. The environmental calculus isn't straightforward - manufactured sand reduces ecosystem destruction but increases carbon footprint. The optimal solution likely involves both, strategically deployed.

Buildings eventually get demolished. What if we treated demolished concrete as a sand source rather than landfill waste?

Recycled concrete aggregate is gaining traction as research validates its performance. New studies confirm that properly processed recycled concrete can replace 20-30% of natural sand in new concrete without compromising strength. Some applications can use 100% recycled content.

The global construction industry generates approximately 3 billion tonnes of demolition waste annually. If even 30% were recycled into aggregate, it would offset 900 million tonnes of natural sand extraction - nearly 2% of global consumption.

If 30% of demolition waste were recycled into aggregate, it would offset 900 million tonnes of natural sand extraction annually - nearly 2% of global consumption.

Challenges remain in scaling recycling infrastructure. Concrete must be separated from other demolition materials, crushed to specific sizes, and tested for quality. The logistics are more complex than simply mining a riverbed. But several European countries have made recycled aggregate mandatory for public infrastructure projects, proving feasibility.

The most profound solution might involve moving beyond concrete entirely for many applications.

Sustainable building materials are emerging across multiple categories:

Hempcrete uses industrial hemp fibers mixed with lime to create a carbon-negative building material. It absorbs more CO2 during growth than is emitted during production. Structural limitations prevent its use in high-rises, but it's viable for residential construction.

Bamboo grows 20 times faster than traditional timber and achieves compressive strength comparable to concrete in engineered applications. Southeast Asian architects are pioneering bamboo construction techniques that could reduce concrete demand.

Cross-laminated timber (CLT) enables wooden high-rise construction previously impossible with traditional framing. Buildings up to 18 stories have been constructed with CLT, sequestering carbon rather than emitting it.

Mycelium composites use fungal networks to bind agricultural waste into building materials. Still experimental, but pilot projects demonstrate potential for insulation and non-structural applications.

Technology alone won't solve the sand crisis without economic reforms that account for environmental costs.

Currently, sand pricing reflects extraction and transportation costs, not the value of ecosystem services or long-term resource availability. A tonne of river sand might cost $5, but the environmental damage from extracting it - lowered water tables, habitat destruction, coastal erosion - imposes costs potentially worth hundreds of dollars.

The global natural sand market projects steady growth to 2,099 million tonnes by 2035, worth $99 billion. Yet these projections assume continued externalization of environmental costs. Incorporating true costs would fundamentally alter market dynamics.

Several policy mechanisms could align prices with reality:

Extraction levies based on environmental impact rather than volume could fund restoration and create incentives for alternatives. Norway's sand extraction tax funds coastal monitoring and habitat restoration.

Tradable sand quotas similar to fishing rights would cap total extraction while allowing market mechanisms to allocate supply efficiently. The scarcity would be explicit rather than hidden.

Recycled content mandates requiring minimum percentages of recycled aggregate in concrete would create guaranteed demand for circular materials.

Extended producer responsibility making concrete producers financially liable for end-of-life recycling would internalize disposal costs and incentivize recyclability.

The economic transition will be disruptive. Construction costs would rise as sand prices reflect true scarcity. But the alternative - exhausting supplies while destroying ecosystems - imposes far greater long-term costs.

The sand crisis is fundamentally a governance failure. Most sand exists in commons - riverbeds, coastlines, ocean floors - making sustainable management a collective action problem.

Effective regulation requires coordination across multiple scales:

International frameworks are needed because sand flows across borders while environmental impacts don't respect boundaries. The United Nations Environment Programme has called for global sand governance, but implementation remains minimal.

National policies must balance development needs against resource sustainability. China's experience shows that regulation works - river sand extraction declined significantly after strict controls, though black markets partially offset the gains.

Local enforcement is critical since sand extraction is inherently local. Community-based monitoring, supported by technology like satellite imagery and drone surveillance, has proven more effective than distant bureaucracies in several pilot programs.

The legal framework challenges include definitional ambiguity about what constitutes sustainable extraction, jurisdictional disputes over offshore resources, and inadequate penalties that make violations economically rational.

Successful models are emerging. The Netherlands has established comprehensive marine spatial planning that designates extraction zones while protecting ecosystems. Australia's sand mining in Queensland operates under strict environmental bonds that companies forfeit if restoration targets aren't met.

The sand crisis forces a confrontation with an uncomfortable truth: the physical infrastructure of modern civilization depends on consuming a finite resource faster than nature can replenish it.

We've treated sand as infinite because it's literally beneath our feet. That assumption is collapsing. The next decade will determine whether we transition to sustainable alternatives or face infrastructure constraints that limit development.

The path forward requires multiple simultaneous shifts. Technological innovation must produce viable alternatives at scale. Economic systems must price environmental costs honestly. Governance frameworks must balance development with resource stewardship. Social norms must shift from viewing sand as waste material to recognizing it as precious.

What happens when sand runs out? We don't have to find out. The solutions exist - manufactured alternatives, recycled aggregates, alternative materials, sustainable extraction practices. What's missing is the collective will to implement them before the crisis becomes catastrophic.

The choice is stark: transform how we build, or watch the foundation of civilization erode, one grain at a time.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

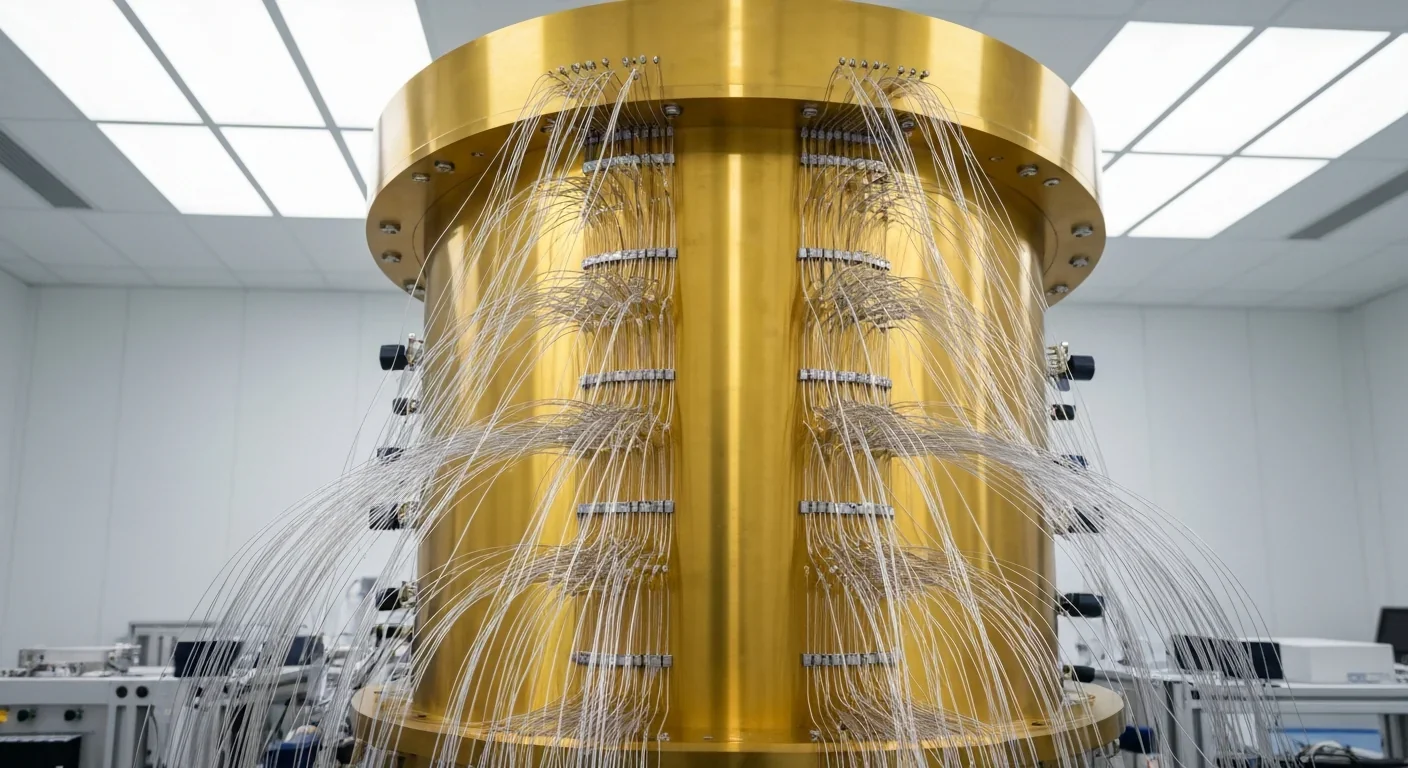

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.