3D-Printed Coral Reefs: Can We Engineer Marine Recovery?

TL;DR: Insect protein farms are transforming food production by converting organic waste into high-quality protein with unprecedented efficiency, dramatically lower environmental impact, and scalable economics that could reshape global agriculture within a decade.

By 2030, the global food system will need to feed nearly 9 billion people. Scientists predict that traditional livestock farming can't scale fast enough without devastating the planet. But what if the solution isn't bigger farms or better technology for raising cows and chickens? What if it's abandoning mammals and birds altogether for something humanity has overlooked for millennia: insects.

Right now, in warehouses from Bulgaria to Thailand, a quiet revolution is unfolding. Trillions of black soldier flies, crickets, and mealworms are transforming food waste into premium protein at a fraction of the environmental cost of conventional livestock. These operations aren't fringe experiments anymore. They're industrial-scale facilities backed by venture capital, regulatory approval, and growing consumer acceptance.

The science behind insect protein farms centers on one remarkable process: bioconversion. Insects like the black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) consume organic waste, from spoiled vegetables to brewery byproducts, and convert it into high-quality protein with astonishing efficiency.

Feed conversion ratio (FCR) measures how much feed an animal needs to gain one kilogram of body weight. The lower the number, the more efficient the animal. House crickets achieve an FCR of 0.9 to 1.1, meaning they need less than 1.1 kg of feed to produce 1 kg of body mass. Compare that to broiler chickens at 1.6, pigs ranging from 1 to 3, and beef cattle sitting at a staggering 4.5 to 7.5.

Why are insects so efficient? They're poikilothermic, which means they don't waste energy maintaining body temperature like mammals do. They also mature incredibly fast. Black soldier fly larvae fed mixed organic waste achieve hatchability rates of 98.7% and survival rates of 98.2%, with the shortest hatching time of just 3.1 days. The same larvae recorded a specific growth rate of 28% and an FCR of 1.1.

Recent advances at Nasekomo in Bulgaria have pushed efficiency even further. Their fully automated platform reports a feed conversion ratio of just 25%, meaning 4 kg of substrate yields 1 kg of insect protein. That level of efficiency makes traditional livestock look wasteful by comparison.

Livestock farming accounts for roughly 14.5% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Cattle alone contribute massive amounts of methane, a greenhouse gas 86 times more potent than CO2 over a 20-year period. Insect farming slashes those emissions dramatically.

The carbon footprint of insect protein production is minuscule compared to beef, pork, or poultry. Black soldier fly farms emit approximately 0.3 kg of CO2-equivalent per kilogram of protein produced. Beef production? Between 50 to 100 kg of CO2-equivalent per kilogram of protein. That's a reduction of over 99%.

Water use tells a similar story. Insect farming requires significantly less water than conventional livestock. Crickets need about 1 liter of water per kilogram of protein, while beef requires 15,000 liters for the same amount.

Land efficiency is where insects truly shine. Vertical farming setups allow insect operations to stack production in compact facilities. A warehouse the size of a basketball court can produce as much protein as a cattle ranch covering hundreds of acres. Insect farming enables urban and peri-urban production, reducing transportation emissions and bringing protein production closer to consumption centers.

Then there's the frass, the byproduct left after insects consume organic waste. Unlike manure from cattle or pigs, which poses environmental hazards when mismanaged, insect frass is rich in nitrogen and phosphorus and has a low carbon-to-nitrogen ratio, making it ideal for composting and soil enrichment. Poultry waste processed by black soldier fly larvae yields frass with C:N ratios between 16.9 and 17.8, perfect for rapid composting. Instead of waste creating pollution, it becomes a valuable agricultural input.

The insect protein market is experiencing explosive growth. In 2023, the global market was valued at approximately USD 185.8 million. Analysts project it will reach USD 1.14 billion by 2033, representing a compound annual growth rate of 19.8%. Some forecasts are even more bullish, predicting the market could hit USD 3.3 billion by 2030.

What's driving this growth? Feed demand, primarily. The aquaculture industry is hungry for sustainable protein sources, and black soldier fly larvae are increasingly used as fish feed. Fish farming operations face criticism for relying on wild-caught fish to produce fishmeal, depleting ocean stocks. Insect protein offers a closed-loop alternative that doesn't stress marine ecosystems.

Pet food represents another massive opportunity. Premium pet food brands are incorporating cricket and mealworm protein into their formulations, marketing them as sustainable and hypoallergenic alternatives to chicken or beef. The nutritional profile is compelling: cricket flour contains more protein than meat and eggs, along with essential amino acids, omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids, vitamins, and minerals.

Automation is making insect farming increasingly cost-competitive. Nasekomo's fully automated system reduces labor costs and increases consistency. Mealworm breeding operations have transitioned from small home setups using plastic containers to industrial facilities with climate-controlled environments maintaining temperatures between 20°C and 30°C.

Startups are leading the charge. Companies like Protix, Ynsect, and AgriProtein have raised hundreds of millions in venture funding. Agroloop in Hungary operates Central Europe's first commercial insect protein plant. These aren't garage operations; they're multimillion-dollar facilities with serious production capacity.

But the sector isn't without challenges. Several high-profile companies have hit financial turbulence. Ynsect and Agronutris in France have explored restructuring options, with Ynsect considering a third-party takeover and Agronutris filing a safeguard plan. Capital intensity remains an issue. Building industrial-scale insect farms requires significant upfront investment, and market adoption hasn't grown fast enough to generate the revenues some investors expected.

For all its environmental and economic promise, insect protein faces a fundamental barrier in many Western markets: disgust. Entomophagy, the practice of eating insects, is common in parts of Africa, Asia, and Latin America, where over 2,000 species are consumed regularly. But in Europe and North America, insects are associated with pests, not food.

Research on Italian consumers' willingness to adopt insect-based foods reveals the complexity. Protection motivation theory suggests people weigh perceived threats (environmental degradation, food insecurity) against their ability to adopt protective behaviors (eating insects). When the environmental benefits are clearly communicated, and products are presented in familiar formats like protein bars or pasta, acceptance increases.

Product format matters enormously. Whole crickets on a plate? Hard sell. Cricket flour blended into sustainable pasta? Much easier. Researchers found that adding cricket flour to pasta significantly increased the nutritional profile without compromising safety or taste, provided the ratio was carefully managed.

Marketing strategies focus on benefits rather than the ingredient itself. Brands emphasize protein content, sustainability credentials, and allergen-friendly profiles. "High-protein, eco-friendly nutrition" resonates better than "ground-up bugs."

Regulatory approval helps normalize insect consumption. The European Union has approved several insect species for human consumption, including crickets, mealworms, and locusts. The EU's Novel Food Regulation framework assesses safety and labeling requirements, giving consumers confidence that insect products meet rigorous standards.

Generation matters too. Younger consumers, particularly those born after 1990, show higher openness to alternative proteins. They've grown up with climate anxiety and are more willing to make dietary changes to reduce their environmental footprint. As this demographic gains purchasing power, demand for insect protein is likely to grow.

Protix, based in the Netherlands, operates one of the world's largest insect protein facilities. They produce black soldier fly larvae for animal feed, focusing on aquaculture and pet food. Their vertical farming approach maximizes production density while minimizing land use. Protix has secured partnerships with major feed companies, integrating insect protein into established supply chains.

Aspire Food Group in North America focuses on cricket farming for human consumption. They've developed a range of consumer products, including protein powders, snack bars, and baking flour. Their strategy centers on making cricket protein accessible and familiar, positioning it alongside other alternative proteins like pea and soy.

Ynsect, despite recent financial difficulties, remains a significant player. They specialize in mealworm production for animal feed and organic fertilizer. Their French facilities use proprietary vertical farming technology to produce tens of thousands of tons annually. The company's challenges highlight the sector's growing pains, but their technological innovations continue to influence the industry.

Agroloop, Central Europe's first commercial insect protein plant, demonstrates regional expansion. Based in Hungary, they process local organic waste streams into insect protein and frass-based fertilizers. Their model emphasizes circular economy principles, turning what would be landfill waste into valuable agricultural inputs.

AgriProtein, operating primarily in South Africa, takes a waste-management approach. They collect organic waste from urban areas, feed it to black soldier fly larvae, and produce protein meal and oil. The frass goes to agricultural operations as fertilizer. This three-product model, protein, oil, and fertilizer, creates multiple revenue streams.

These companies share common strategies: automation, vertical integration, and partnerships with established industries. They're not trying to compete with beef in supermarkets tomorrow. Instead, they're embedding insect protein in supply chains where performance and sustainability matter more than consumer visibility.

Regulation determines whether insect protein remains a niche curiosity or becomes mainstream. Different regions have taken different approaches, and those policies are shaping where the industry thrives.

The European Union has been relatively progressive. Under the Novel Food Regulation, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) evaluates insect species for human consumption. Since 2021, dried yellow mealworms, migratory locusts, house crickets, and lesser mealworms have received approval. Labeling requirements ensure transparency, and maximum residue limits address safety concerns like heavy metal accumulation.

The United States has been slower and more fragmented. The FDA treats insects as food ingredients, but comprehensive regulatory guidance is lacking. Individual states set their own rules, creating a patchwork that complicates interstate commerce. However, the Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO) has approved some insect proteins for animal feed, opening the pet food market.

Asia presents a mixed picture. Countries like Thailand, where entomophagy is culturally embedded, have streamlined approval processes. China, recognizing food security challenges, is investing heavily in insect farming R&D and infrastructure. Japan is exploring insects as part of its strategy to increase food self-sufficiency.

Policy support extends beyond food safety. Some governments offer subsidies or grants for sustainable protein production, recognizing insect farming's environmental benefits. Research programs funded by public institutions investigate optimization of breeding, nutrition, and processing, reducing the knowledge barriers for new entrants.

Hazard monitoring remains critical. Potential risks include allergenicity (insect proteins can trigger reactions in people allergic to shellfish), microbial contamination, and the accumulation of heavy metals or pesticides from feed substrates. Regulatory frameworks that address these concerns without stifling innovation will determine the sector's trajectory.

Where does insect protein go from here? The next decade will likely see three major developments: technological maturity, market diversification, and cultural normalization.

Technological maturity means more efficient production at lower costs. Advances in automation, selective breeding, and substrate optimization will continue. Genetic research on species like black soldier flies could enhance growth rates, disease resistance, and nutritional profiles. AI-driven monitoring systems will optimize temperature, humidity, and feeding schedules in real time, maximizing yields while minimizing resource use.

Market diversification will expand beyond animal feed and niche human foods. Insect protein will increasingly appear in familiar products: burger patties, protein shakes, breakfast cereals, snack chips. Ingredient companies will supply insect protein isolates to food manufacturers, who'll blend them into existing formulations. Most consumers won't choose "insect burgers"; they'll buy "high-protein, sustainable burgers" that happen to contain cricket flour.

The global insect protein market's projected growth to over USD 1 billion by 2033 reflects this trajectory. As production scales, prices will drop, making insect protein competitive with conventional animal proteins on cost alone. When sustainability is the bonus rather than the premium, adoption accelerates.

Cultural normalization requires time and exposure. Just as sushi went from exotic to ubiquitous in the West over a few decades, insect protein needs visibility and familiarity. Celebrity chefs incorporating crickets into gourmet dishes, athletes endorsing insect protein supplements, and mainstream brands adding mealworm flour to their product lines will all contribute.

Education matters. The more people understand the environmental stakes, the more open they become to alternatives. Climate-friendly nutrition campaigns by dietitians and environmental groups are shifting perceptions, framing insects as responsible rather than radical.

Integration with waste management could be transformative. Cities struggle with organic waste disposal; landfills produce methane, and composting requires space and time. Insect-based organic waste management offers a solution that's faster, more compact, and yields valuable outputs. Municipal partnerships with insect farms could create circular urban food systems, where yesterday's vegetable scraps become tomorrow's fish feed.

Global food security pressures will drive adoption. By 2050, the world needs to produce 70% more food to feed a projected population of nearly 10 billion. Land and water constraints make traditional livestock expansion untenable in many regions. Insects offer a protein source that's scalable, resource-efficient, and adaptable to diverse climates.

The shift from chickens to crickets isn't just about finding a new protein source. It's about fundamentally rethinking how humans produce food. For the last 10,000 years, agriculture meant controlling land, planting crops, and raising animals in fields and pastures. That model worked when the human population was small and the planet's resources seemed endless.

We're in a different era now. Climate change, biodiversity loss, and resource scarcity demand new approaches. Insect farming represents a biological solution to an industrial problem. Instead of scaling up inefficient systems, it redesigns protein production from the ground up.

The insects themselves are doing the work. They're not engineered organisms or synthetic proteins; they're species that have evolved over millions of years to excel at converting organic matter into biomass. Humans are simply creating the conditions for them to do what they do best, at scale.

This isn't a silver bullet. Insect protein won't replace all livestock overnight, and it shouldn't. Cows grazing on land unsuitable for crops can be part of sustainable food systems. But in contexts where efficiency, land use, and emissions matter, insects outperform traditional livestock by nearly every metric.

The real question isn't whether insect farming will grow. It will. The question is how fast, and whether it grows fast enough to make a meaningful difference before food systems face irreversible stress. The technology exists. The economics are improving. The regulatory pathways are opening. What remains is cultural acceptance and political will.

If future generations look back at the 2020s, they might see this decade as the moment humanity began shifting from extraction to integration, from depleting resources to working with biological systems. Insect protein farms, with their vertical towers and humming larvae, might seem as ordinary to them as chicken farms seem to us now.

The revolution from chickens to crickets isn't coming. It's already here, quietly transforming food production in warehouses across the world. The only question is whether enough people notice in time to embrace it.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

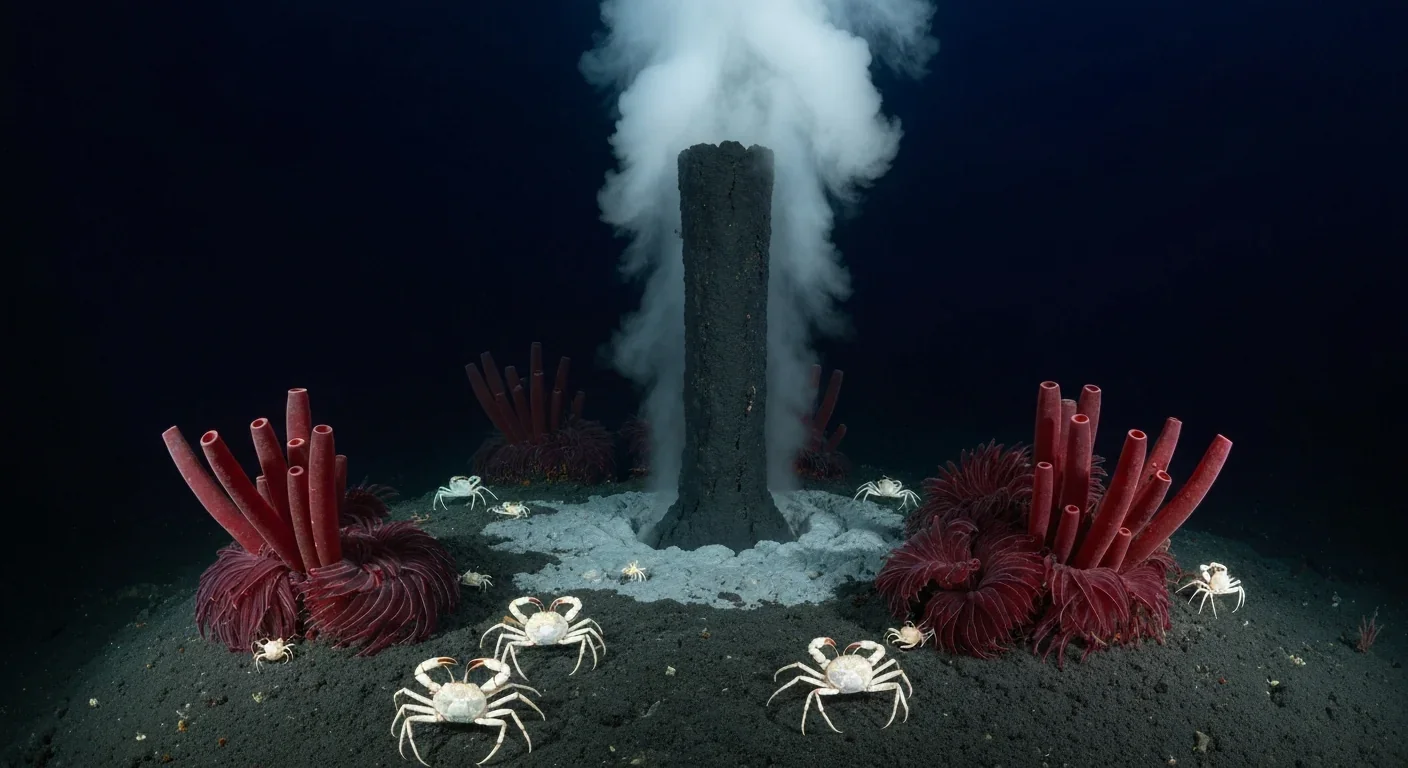

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.