AI Cameras Save Sea Turtles in Fishing Nets

TL;DR: Climate change is forcing alpine species to migrate upward on mountains at rates they can't sustain, creating an 'escalator to extinction' as specialized organisms reach summits with nowhere left to go. Mountains warming twice as fast as global averages are witnessing unprecedented biodiversity loss.

By 2100, researchers predict that one-third of all species could face serious extinction risk if global temperatures continue rising. But high on the world's mountains, that crisis is already unfolding. Alpine species, perfectly adapted to their cold, isolated peaks over millions of years, are being squeezed into smaller and smaller habitats as warming temperatures force them upward. There's just one problem: mountains don't go up forever. For thousands of species, the escalator to extinction has already begun its inexorable climb.

The situation is particularly urgent because mountain environments are warming faster than almost anywhere else on Earth. While global average temperatures have risen about 1°C since pre-industrial times, alpine regions are heating at roughly twice that rate. In the Alps, temperatures have increased by approximately 2°C over the past century, and projections suggest another 2-4°C rise by 2100. This accelerated warming creates a compression effect where entire ecosystems are being pushed into ever-shrinking zones.

Mountains harbor an astonishing concentration of the world's biodiversity. Though they cover just 12% of Earth's land surface, they're home to 85% of the world's amphibian, bird, and mammal species. Their steep elevation gradients create numerous microclimates within short distances, allowing diverse species to coexist in specialized niches.

But this very specialization makes alpine organisms extraordinarily vulnerable. Unlike lowland species that might migrate hundreds of miles to find suitable climate conditions, mountain species are trapped in what ecologists call "sky islands." These isolated peaks are surrounded by warmer, inhospitable lowlands that alpine specialists simply cannot cross.

While global temperatures have risen 1°C, alpine regions are warming at twice that rate, creating a compression effect where entire mountain ecosystems are being pushed into ever-shrinking zones.

The vulnerability runs deeper than geography. Alpine plants and animals have evolved exquisite adaptations to harsh conditions including intense UV radiation, extreme temperature fluctuations, short growing seasons, and nutrient-poor soils. They grow slowly, reproduce infrequently, and live in delicate balance with their environment. These traits made them supremely suited for stable alpine conditions but leave them ill-equipped for rapid change.

Consider the American pika, a small rabbit relative that lives in rocky alpine areas of western North America. Pikas cannot tolerate temperatures above 25°C for more than a few hours because they're built like miniature furnaces, conserving heat in frigid environments. As valleys warm, pika populations have already disappeared from lower elevations, retreating upslope in search of cooler refuges. When they reach the summit, there's nowhere left to go.

Scientific monitoring reveals the migration is already well underway. A comprehensive study tracking alpine plant communities found that vegetation zones have shifted upward by an average of 2.7 meters per decade since 1930. That might sound modest, but it represents a fundamental reorganization of mountain ecosystems.

The rate of upward movement varies considerably by species and region. Fast-dispersing plants with wind-borne seeds can colonize new territory relatively quickly, but many alpine specialists are slow movers. Their seeds may need years to germinate in harsh conditions, and established plants can be centuries old. Trees are moving upward too: the timberline, marking where forests give way to alpine meadows, is creeping higher at rates of 1-3 meters per year in many mountain ranges.

The problem is that warming is outpacing migration. Temperature isotherms, the boundaries of specific temperature zones, are shifting upward at approximately 11 meters per decade in response to climate change. Many species simply can't keep pace with their preferred climate as it races up the mountain.

"Observed changes largely fell within random expectations, accounting for geometric constraints. Many range shifts are consistent with random processes rather than deterministic extinction drivers."

- Science study on mountain biodiversity

This creates what scientists call "range debt," where species occupy temperatures warmer than their optimal range because they haven't been able to track their climate niche upward fast enough. Plants rooted in place face this challenge acutely, but even mobile animals like birds and insects struggle when their food sources, nesting sites, and hibernation refuges can't migrate at the same pace.

Across the world's mountains, species are reaching their limits. On Mount Mansfield in Vermont, the summit supports the only alpine tundra in the state, home to rare species like Bicknell's thrush and several endemic plants found nowhere else. As temperatures rise and the treeline advances, this tiny patch of tundra is shrinking. Within decades, it could vanish entirely, taking its unique inhabitants with it.

The situation is replicated on mountaintops worldwide. In the Pyrenees, research projects that endemic plant species could lose 60-80% of their suitable habitat by 2080 under moderate warming scenarios. Species restricted to the highest peaks have literally nowhere to go when their current habitat becomes unsuitable.

The Himalayas face particularly severe threats. Climate change in this region is causing glacier retreat, shifting monsoon patterns, and rapid warming that threatens both biodiversity and the 240 million people who depend on Himalayan ecosystems. High-altitude species including the snow leopard, Himalayan tahr, and countless plant species face contracting ranges as their habitat is squeezed between warming lowlands below and barren summits above.

There are glimmers of adaptation. Recent research on pikas found they're more resilient than initially predicted, with some populations adjusting their behavior by foraging in cooler morning and evening hours. Alpine marmots are shifting their activity patterns to cope with warmer conditions. But behavioral flexibility has limits when the fundamental habitat disappears.

The loss of alpine species triggers ripples through entire ecosystems. Mountain environments function as interconnected webs where each species plays specific roles. When key species disappear, the effects cascade.

Alpine plants are primary producers that anchor these ecosystems, converting sunlight and nutrients into biomass that feeds herbivores. They also stabilize soils on steep slopes, prevent erosion, and regulate water flow. Their loss can destabilize entire mountainsides. In the European Alps, changes in vegetation are already altering avalanche patterns and increasing rockfall risk as plant roots no longer hold slopes as effectively.

Pollinators face severe pressure in alpine zones. Many mountain flowers depend on specialized pollinators adapted to harsh conditions, like bumblebees that can generate body heat to fly in cold temperatures. As both plants and pollinators shift ranges at different rates, the timing of flowering and pollinator emergence can become mismatched, threatening reproduction for both.

Temperature isotherms are shifting upward at 11 meters per decade while many alpine species can only migrate at 2.7 meters per decade - they're losing the race to track their climate.

Predator-prey relationships are being disrupted too. Birds like the rock ptarmigan rely on camouflage against snow for protection. But as snow cover decreases and arrives later in the season, these birds become increasingly vulnerable to predators against the darker background of bare rock and vegetation.

Perhaps most concerning is what ecologists call "biotic homogenization." As alpine specialists decline, generalist species from lower elevations expand upward, replacing unique alpine communities with more cosmopolitan assemblages. This process is eroding the distinctive character of mountain ecosystems worldwide, replacing biodiversity hotspots with ecologically generic spaces.

The extinction threat varies dramatically across the world's mountain ranges, shaped by geography, climate patterns, and human pressures.

Tropical mountains face particularly acute risks. Species there evolved in stable temperatures with minimal seasonal variation, so they have narrow thermal tolerances and little capacity to adjust to warming. A tropical mountain species might be adapted to a temperature range of just 3-4°C, compared to 10-15°C for temperate alpine species. Even small temperature increases can push tropical mountain species beyond their physiological limits.

Island mountains like those in Hawaii and New Zealand face additional challenges. Their species evolved in isolation and have no nearby peaks to colonize if conditions become unsuitable. Mountain biodiversity on islands is being squeezed between rising temperatures and the ocean, with truly nowhere to go.

Meanwhile, some continental mountain ranges offer slightly better prospects. The Rockies, Andes, and Himalayas extend thousands of kilometers, providing potential corridors for species to shift to higher latitudes as well as higher elevations. But these movements require crossing valleys, roads, and human settlements, creating obstacles that many species cannot overcome.

The compounding effect of other stressors amplifies climate risks. In the Alps, intensive tourism, grazing, and development fragment habitats and create barriers to migration. In the Himalayas, deforestation and agriculture in lower zones eliminate potential refuges. Where mountains are already degraded by human activity, species have even less capacity to adapt to warming.

Conservation efforts are scrambling to respond, but the challenges are immense. Traditional approaches like establishing protected areas help, but are insufficient when the habitat itself is disappearing. You can't protect an alpine meadow that transforms into forest or bare rock as the climate shifts.

Some conservationists are exploring more interventional strategies. "Assisted migration" involves physically relocating species to suitable habitats farther upslope or on higher peaks. It's controversial because moving species to new locations risks introducing them as invasives that disrupt their new ecosystems. But for species facing certain extinction in their current range, it may become necessary.

Ex situ conservation, preserving genetic material in seed banks and botanical gardens, serves as an insurance policy. The Millennium Seed Bank in the UK has prioritized collecting seeds from threatened alpine plants. While this preserves genetic diversity, it's a poor substitute for living, functioning ecosystems.

"Limiting warming to 1.5°C versus 2°C could reduce extinction risk by up to 50% for vulnerable species. Every fraction of a degree matters tremendously."

- Climate research on extinction prevention

The most effective conservation approach addresses the root cause: slowing and eventually reversing climate change. Every fraction of a degree matters tremendously for alpine species. Research suggests that limiting warming to 1.5°C versus 2°C could reduce extinction risk by up to 50% for vulnerable species.

Mountain communities are also developing adaptation strategies to protect both biodiversity and human livelihoods. In some regions, sustainable tourism models fund conservation while reducing environmental impact. Restrictions on development in critical habitats can maintain corridors for species movement. Indigenous communities' traditional ecological knowledge is being recognized as valuable for understanding and managing mountain ecosystems under change.

What's happening on mountains serves as both warning and harbinger for the rest of the planet. Alpine ecosystems are experiencing climate impacts decades ahead of lowland regions, offering a preview of challenges that will eventually affect all biodiversity.

The retreat of mountain glaciers is among the most visible signs of change. Glaciers worldwide have lost trillions of tons of ice since 1850, with the pace accelerating dramatically in recent decades. As these ice masses disappear, they leave behind newly exposed landscapes where succession begins anew. These barren zones will take decades or centuries to develop mature ecosystems, if suitable conditions persist long enough.

The loss of glaciers has cascading effects far beyond mountains. Over 2 billion people depend on glacier-fed rivers for water, and declining snowpack threatens water security across multiple continents. The ecological and human consequences ripple outward from mountains to affect entire regions.

Surprisingly, some alpine zones are experiencing increases in biodiversity, though not in ways that conservationists celebrate. High-elevation lakes in Alberta have seen fish diversity increase over the past 50 years as warming conditions allow species from lower elevations to colonize higher waters. But these "winners" often replace unique native species that evolved in isolation, resulting in more biodiversity by the numbers but less evolutionary distinctiveness.

The biodiversity crisis unfolding on the world's mountains demands urgent attention, not just because of what we stand to lose, but because of what it reveals about the pace and scale of change our planet faces.

Mountains have always seemed permanent, their peaks eternal markers on the landscape. But the ecosystems they support are proving surprisingly fragile, fine-tuned over millennia to conditions that are shifting faster than many species can adjust. The plants clinging to summits today may not have time to evolve heat tolerance. The animals adapted to cold may not be able to relocate fast enough to track their disappearing climate.

Mountains harbor 85% of the world's amphibian, bird, and mammal species on just 12% of Earth's land surface - making them irreplaceable biodiversity hotspots now under severe threat.

Yet the story isn't finished. Scientific monitoring is improving rapidly, giving us better data to understand which species and ecosystems face the greatest risks. Conservation strategies are evolving beyond simple protection to active intervention where necessary. Most importantly, the window to limit warming and prevent the worst outcomes hasn't closed.

Every alpine flower that blooms at record elevations, every pika population adjusting its behavior, every community protecting mountain habitats contributes to resilience. But time is the resource we can't manufacture. The longer we delay addressing climate change, the more species will reach their summits with nowhere left to climb.

Mountains have always challenged us to look up, to reach beyond the comfortable lowlands toward something higher. The escalator to extinction asks whether we'll rise to the challenge of protecting the remarkable diversity of life that evolved to thrive on those heights, or watch as it slips away, one lost species at a time, from peaks that are running out of room.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

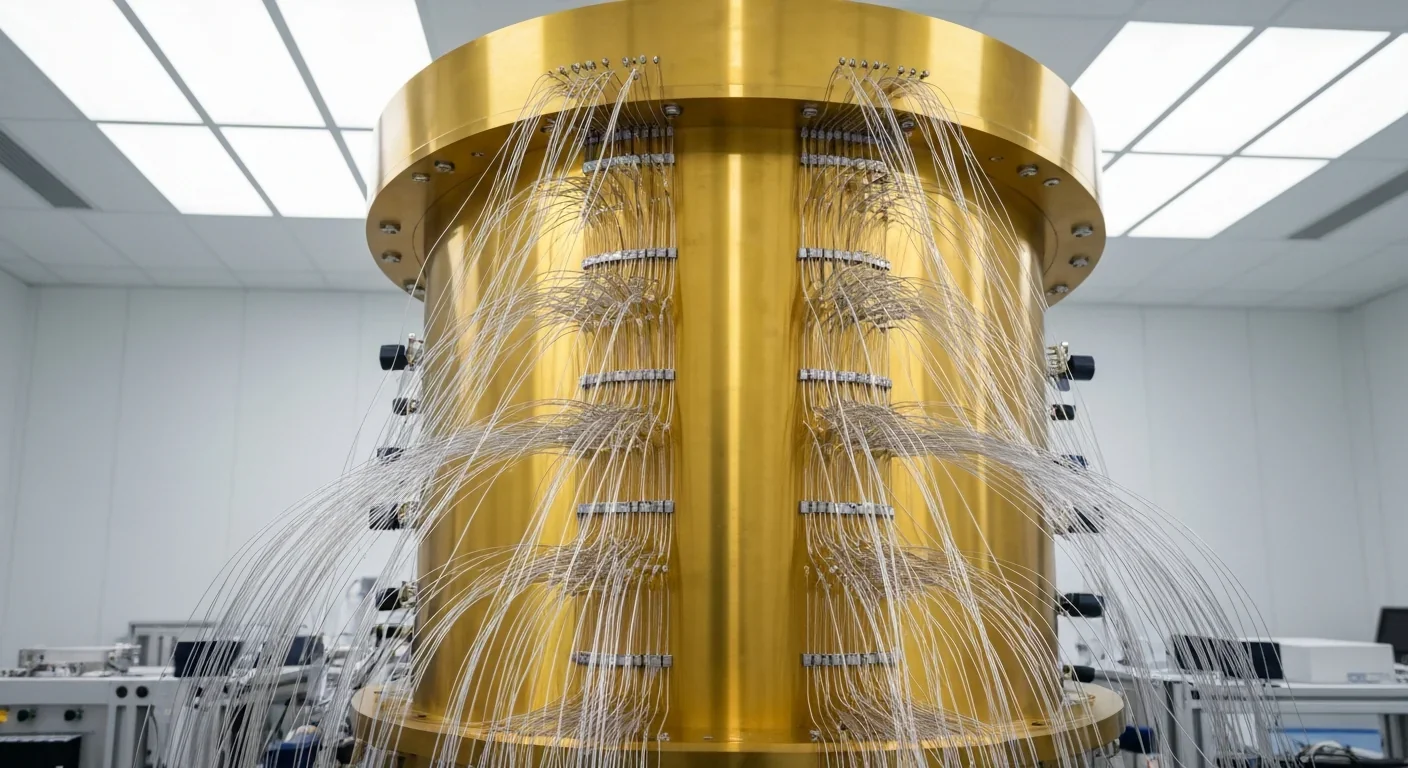

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.