AI Cameras Save Sea Turtles in Fishing Nets

TL;DR: Microplastic particles now fall from the sky globally through rain and atmospheric deposition, contaminating even remote wilderness areas. Scientists have documented over 1,000 metric tons annually in Western U.S. protected lands alone, with particles originating from roads, textiles, and ocean spray traveling thousands of miles through atmospheric circulation.

The next time you feel raindrops on your skin, consider this unsettling reality: you're not just getting wet. You're being showered with microscopic plastic particles that have traveled through the atmosphere, sometimes across continents and oceans, before landing on your face, your garden, your drinking water.

Microplastics aren't just floating in the ocean anymore. They've infiltrated Earth's atmospheric circulation system, turning precipitation into a global delivery mechanism for plastic pollution. Scientists have documented plastic particles raining down everywhere from dense urban centers to the most remote wilderness areas on the planet. And unlike acid rain, which regulations eventually controlled, plastic rain appears to be permanent.

In 2020, researchers published a groundbreaking study in Science that fundamentally shifted our understanding of plastic pollution. They collected rainwater samples from national parks and protected wilderness areas across the Western United States, expecting minimal contamination in these pristine environments.

What they found was shocking: more than 1,000 metric tons of plastic particles falling from the sky annually in these protected areas alone. That's the equivalent of 120 to 300 million plastic water bottles literally raining down each year on places we've designated as wilderness sanctuaries.

"We can't stop the microplastic cycle anymore. It's there and it's not going away."

- Janice Brahney, biogeochemist at Utah State University

The discovery was paradigm-shifting because it revealed that plastic pollution isn't contained to landfills, oceans, and rivers. It's become atmospheric, circulating globally through the same systems that distribute water vapor and weather patterns.

The mechanism behind plastic rain involves multiple pathways, all connected to modern human activity. Every day, countless sources release microplastics into the air.

Road surfaces represent one of the largest contributors. As vehicles drive, tires shed synthetic rubber particles, and the friction of traffic grinds road litter and plastic waste into microscopic fragments that become airborne. Highways are particularly prolific microplastic generators.

Textile fibers escape from clothing during wear and washing. These synthetic fibers, typically made from polyester, nylon, and acrylic, shed microscopic particles that enter ventilation systems and eventually the outdoor atmosphere.

Ocean waves break down floating plastic debris and launch particles into the air through sea spray. Research shows that ocean surf contributes significantly to atmospheric microplastic loads, connecting marine pollution directly to atmospheric circulation.

Industrial emissions from manufacturing facilities, waste processing centers, and plastic production plants release particles directly into the air.

Once airborne, these particles behave surprisingly like dust or pollen. They can travel thousands of miles through atmospheric currents. Research from the National Science Foundation found that particle shape determines transport distance: fibers and fragments with higher surface-area-to-volume ratios stay airborne longer and travel farther than compact spheres.

This means microplastics generated in cities don't stay local. They disperse globally, carried by wind patterns, jet streams, and weather systems until precipitation eventually brings them back to Earth.

One of the most disturbing aspects of atmospheric microplastic pollution is its ubiquity. Researchers have documented plastic rainfall across dramatically different environments.

Urban centers show the highest concentrations. A global study of airborne microplastics found alarming levels in cities worldwide, with dense traffic areas showing particularly elevated measurements.

Remote wilderness areas that should be pristine show measurable contamination. In New York's Adirondack Mountains, researchers comparing two remote lakes found microplastics in both, even in a trailless backcountry pond accessible only by bushwhacking through dense forest.

Forests across Europe have become unexpected microplastic repositories. A 2024 analysis revealed that European forests are accumulating plastic particles through atmospheric deposition, essentially functioning as unintended landfills for airborne plastic.

Antarctica itself hasn't escaped. Scientists have detected PFAS chemicals, often co-occurring with microplastics, in Antarctic precipitation, demonstrating that even the most isolated continent on Earth receives atmospheric plastic pollution.

The message is clear: there are no safe havens. Atmospheric circulation doesn't respect geographic boundaries or protected status.

Not all microplastics are created equal. Analysis of precipitation samples reveals a diverse mixture of particle types, sizes, and chemical compositions.

Particle types include fibers from textiles, fragments from broken-down pieces of larger plastic items, films from bags and packaging, and microbeads from personal care products. Research indicates that fibers dominate many samples, reflecting the prevalence of synthetic clothing and fabrics.

Size matters tremendously. Most particles in precipitation measure between 10 and 500 micrometers. The smallest particles, particularly those under 10 micrometers, are most concerning because they can penetrate deeper into human respiratory systems and potentially cross cellular barriers.

Chemical composition varies widely. Polyethylene, polypropylene, polyester, and polystyrene are the most common polymers detected. Each carries different potential health implications because plastics often contain additives: plasticizers, flame retardants, UV stabilizers, and pigments that can leach out once inside organisms.

PFAS co-occurrence represents an additional concern. These "forever chemicals" often appear alongside microplastics in precipitation. A 2024 study in Miami found 20 different PFAS compounds in rainwater at concentrations exceeding EPA drinking water guidelines.

The human health consequences of breathing and consuming airborne microplastics remain incompletely understood, but emerging research paints a concerning picture.

Inhalation exposure may be the primary pathway. Studies suggest we inhale between 68,000 and 70,000 microplastic particles daily, primarily in indoor environments where particles concentrate. These particles accumulate in homes and cars, where we spend most of our time.

Respiratory impacts include chronic pulmonary inflammation. Research has linked microplastic inhalation to lung inflammation that can progress to more serious conditions, including potentially increased lung cancer risk.

Systemic distribution means microplastics don't stay in your lungs. Scientists have found these particles throughout human bodies. They cross the blood-brain barrier, accumulate in organs, and have even been detected in human brain tissue, placental tissue, and bloodstreams.

Chemical exposure compounds the problem. Plastics carry additives designed to modify their properties, and many of these chemicals are endocrine disruptors, carcinogens, or developmental toxins. When microplastics break down inside the body, these chemicals can leach out.

Drinking water contamination adds another exposure route. Although water treatment plants remove approximately 70% of microplastics, some particles inevitably pass through. A 2023 US Geological Survey study estimated that at least 45% of U.S. tap water samples contain detectable PFAS compounds, often co-occurring with microplastics.

"The full scope of health impacts won't be clear for years, possibly decades. We're conducting an uncontrolled experiment on ourselves."

- Environmental health researchers

Microplastic rainfall doesn't just affect people. It's altering ecosystems in ways we're only beginning to document.

Soil contamination accumulates over time as atmospheric deposition continuously adds plastic particles to surface soils. These particles can alter soil structure, affecting water retention, nutrient availability, and microbial communities.

Freshwater systems receive microplastic inputs from both direct atmospheric deposition and runoff from contaminated soils. Lakes, streams, and rivers become repositories for particles that then concentrate through aquatic food webs.

Wildlife exposure occurs through multiple pathways. Animals ingest microplastics in contaminated water and food. Aquatic organisms filter particles from water. Birds incorporate plastic fibers into nests. The full ecological consequences remain poorly understood.

Remote ecosystem vulnerability is particularly concerning. Pristine environments that evolved without plastic suddenly receive regular inputs of synthetic particles. These ecosystems lack any evolutionary adaptation to deal with this novel contaminant.

Documenting atmospheric microplastic pollution requires sophisticated techniques. Researchers employ multiple approaches to identify and quantify these particles.

Collection methods vary by study design. Precipitation samples are gathered using specialized collectors that filter rainwater through fine mesh or filter papers. Air sampling uses high-volume pumps that draw air through filters over extended periods. Deposition samplers collect particles settling from the atmosphere over weeks or months.

Microscopic analysis provides initial identification. Researchers use stereomicroscopes and scanning electron microscopes to visualize particles, assess morphology, and estimate abundance.

Spectroscopic techniques confirm plastic identity. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and Raman spectroscopy identify polymer types by analyzing how materials interact with light. These methods can definitively distinguish plastics from natural particles like pollen or mineral dust.

Standardization challenges complicate cross-study comparisons. Different research groups use varying collection methods, analysis protocols, and size cutoffs, making it difficult to compare results directly. The scientific community is working toward standardized methodologies.

The comparison to acid rain is inevitable, and it reveals both hope and despair.

Acid rain emerged in the 1960s and 1970s as a recognized environmental crisis. Industrial emissions of sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides were creating acidic precipitation that damaged forests, killed fish in lakes, and corroded buildings and monuments.

Regulatory action worked. The Clean Air Act amendments of 1990 established cap-and-trade systems for sulfur dioxide emissions. Industries adopted cleaner technologies. Acid rain decreased dramatically in subsequent decades. The problem, while not eliminated, was substantially controlled.

Plastic rain differs fundamentally. Acid rain resulted from emissions that could be controlled at the source through industrial regulations and technology changes. Plastic pollution comes from ubiquitous consumer products, infrastructure materials, and industrial applications woven throughout modern civilization.

The persistence factor makes plastics uniquely challenging. Once released, plastics don't degrade the way acidic compounds do. They fragment into smaller and smaller pieces but never truly disappear. Every plastic item ever manufactured still exists somewhere in some form.

"It's there and it's not going away" isn't defeatism. It's a recognition that we've created a permanent alteration to Earth's systems.

Despite growing scientific evidence, regulatory frameworks haven't caught up to the atmospheric microplastic problem.

Current regulations focus primarily on ocean plastics, wastewater discharge, and landfill management. Atmospheric pathways remain largely unaddressed in existing environmental legislation.

Air quality standards don't include microplastics. The Clean Air Act and similar international frameworks regulate specific chemical pollutants but haven't been updated to address particulate plastic pollution.

Drinking water guidelines are beginning to emerge. Some jurisdictions are establishing maximum contaminant levels for microplastics in drinking water, though enforcement and testing remain inconsistent.

International coordination remains limited. Plastic pollution crosses borders freely, but regulatory approaches vary dramatically between countries. The lack of global standards hampers effective action.

Research funding has increased substantially in recent years as the scope of the problem has become clear. Understanding must precede effective regulation, and we're still in the understanding phase for atmospheric transport.

The permanence of atmospheric microplastics doesn't mean we're helpless, but it does require realistic expectations about solutions.

Source reduction represents the most effective intervention. Reducing plastic production and use prevents particles from entering the environment in the first place. This means reconsidering packaging choices, clothing materials, and transportation infrastructure.

Material alternatives are emerging. Biodegradable materials, though not without their own complications, offer potential pathways away from persistent synthetic polymers. Research into materials that break down completely without leaving microplastic residues is advancing.

Filtration technologies can reduce exposure. High-quality water filters, particularly reverse osmosis systems, remove most microplastics from drinking water. HEPA air filters reduce indoor air concentrations where we spend most of our time.

Infrastructure changes could reduce major sources. Tire materials that shed fewer particles, road surfaces designed to capture runoff, and textile designs that minimize fiber release would all help.

Waste management improvements prevent plastics from entering the environment where they can fragment and become airborne. Better collection systems, reduced littering, and comprehensive recycling programs all contribute.

Personal actions matter at the margins. Choosing natural-fiber clothing, avoiding single-use plastics, properly disposing of waste, and supporting policy changes all contribute to reducing the problem, even if they can't eliminate it.

We've fundamentally altered one of Earth's basic systems. The water cycle, which has functioned for billions of years to distribute life-essential H₂O across the planet, now also distributes synthetic polymers to every ecosystem and every population.

This reality requires a shift in how we think about plastic pollution. It's not just an ocean problem or a landfill problem. It's an atmospheric problem, a precipitation problem, an everywhere problem.

The science is still emerging. We don't yet know the full health consequences of chronic microplastic exposure. We don't fully understand how these particles will affect ecosystems over decades and centuries. We don't know if there are tipping points where accumulated plastic fundamentally alters biological systems.

What we do know is that plastic particles are falling from the sky right now, have been for years, and will continue indefinitely. The first generation of humans to live under plastic rain is already here. We're that generation.

The question isn't whether we can go back to a plastic-free world; we can't. The question is whether we can prevent the problem from getting worse, whether we can adapt our systems and behaviors to minimize future contamination, and whether we can develop the scientific understanding and regulatory frameworks to protect human health and environmental integrity in a permanently plastic-contaminated world.

The rain keeps falling. What falls with it is now partly our responsibility to control.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

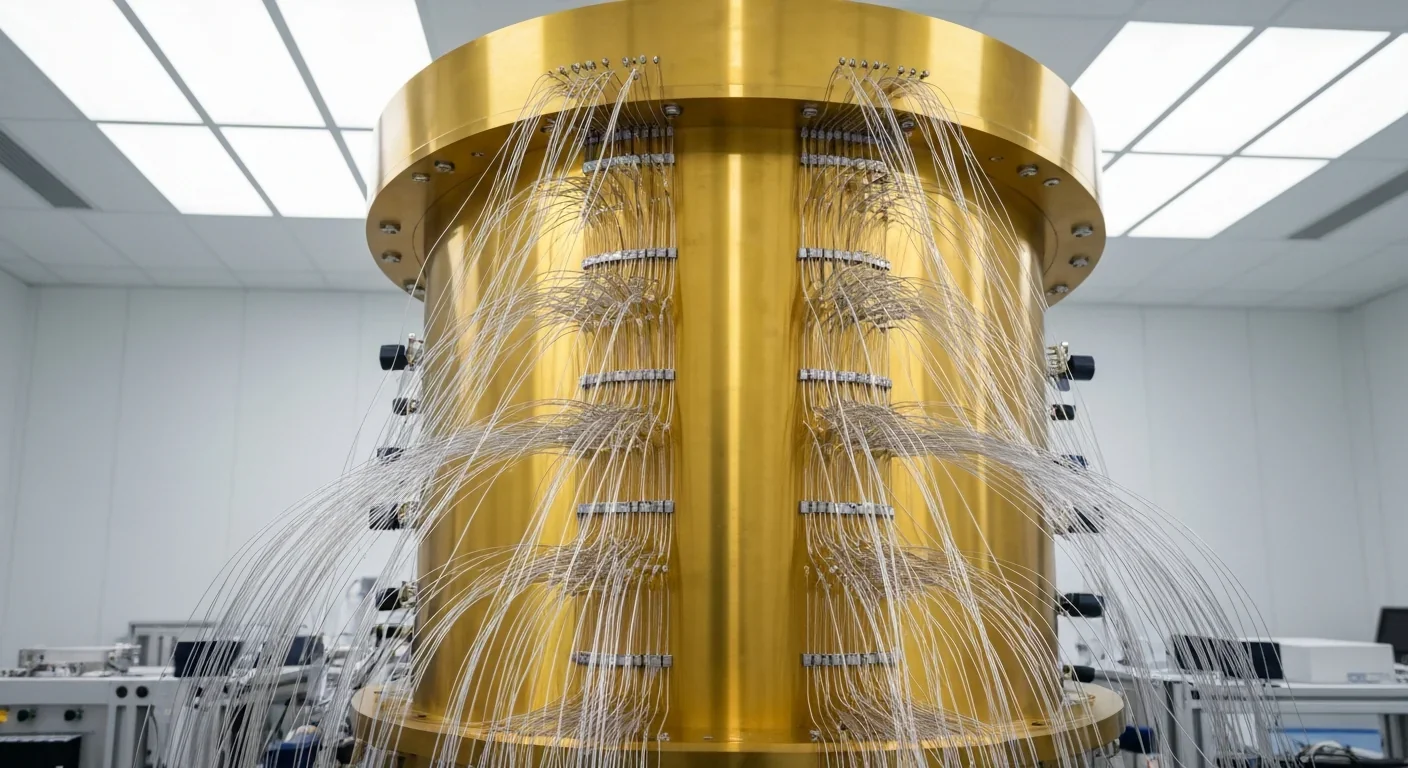

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.