AI Cameras Save Sea Turtles in Fishing Nets

TL;DR: Scientists are using precision fermentation to produce real dairy proteins in fermentation tanks, without cows. Companies like Perfect Day have received FDA approval and are partnering with major food brands. The technology could reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 85-95% compared to conventional dairy while producing molecularly identical proteins.

In a fermentation tank in California, yeast cells are doing something they've never done in nature: producing the exact same proteins that come from cow's milk. No udders, no pastures, no methane emissions. Just microbes following genetic instructions that scientists borrowed from bovines and taught them to execute with precision. Within the next decade, you'll likely consume dairy products made this way without even realizing it, because the proteins are molecularly identical to those from animals. The question isn't whether this technology works anymore - it's what happens when it scales.

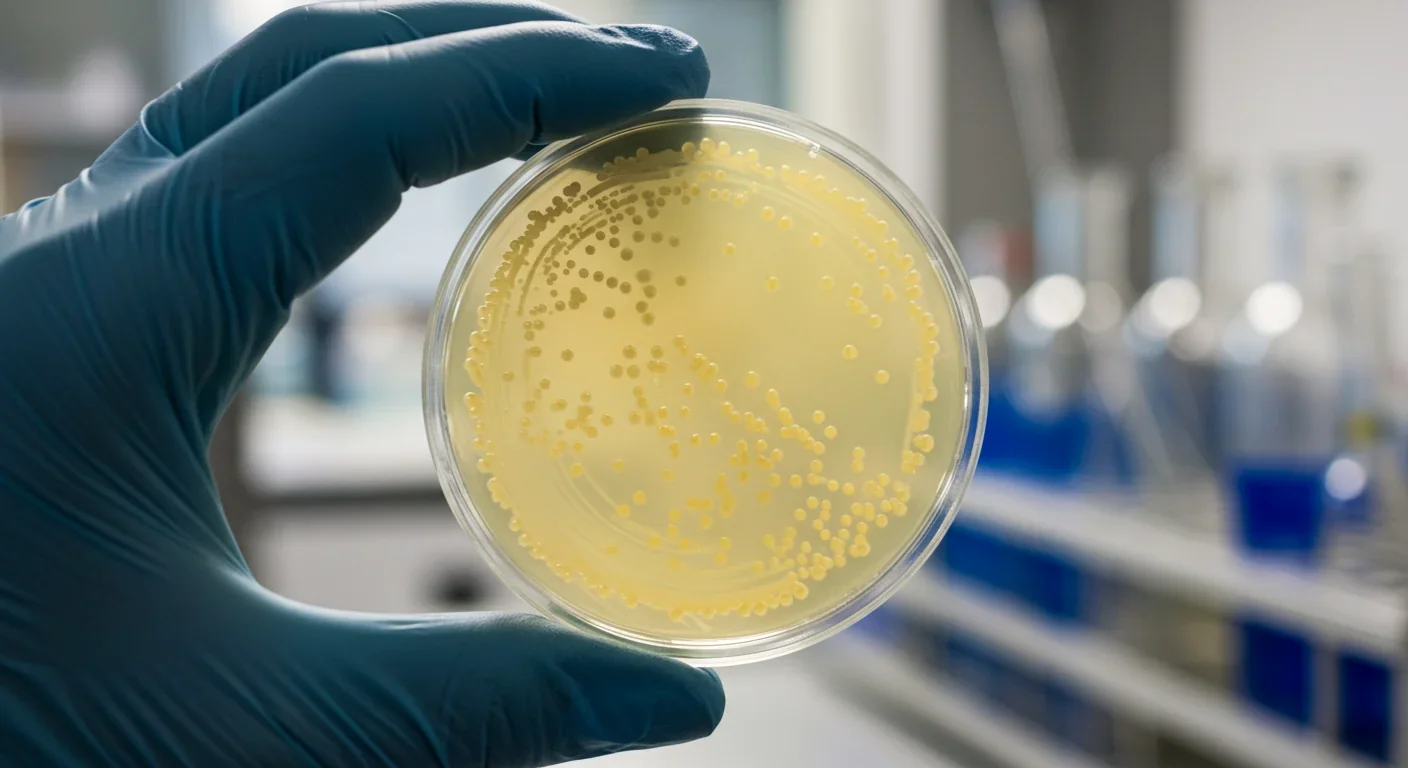

Precision fermentation sounds like science fiction, but the underlying process is surprisingly straightforward. Scientists identify the gene in a cow's DNA that codes for a specific milk protein - whey or casein, for example. They insert that gene into microorganisms like yeast or bacteria, creating what's essentially a living protein factory. When these modified microbes are fed simple sugars in fermentation tanks (the same kind used to brew beer), they produce authentic dairy proteins as part of their metabolic process.

The genius lies in what happens next. After fermentation, the microorganisms are filtered out, leaving behind pure protein that's chemically indistinguishable from what a cow produces. No lactose unless you want it. No cholesterol. No pathogens that might have passed from animal to milk. Just the protein, isolated and ready to be turned into cheese, ice cream, or yogurt. Perfect Day, one of the pioneering companies in this space, has been producing beta-lactoglobulin - a whey protein - since 2020 using a genetically engineered strain of Trichoderma reesei, a fungus.

This isn't fermentation in the traditional sense, where microbes transform ingredients (think yogurt cultures converting milk to yogurt). This is precision fermentation, where microbes serve as biological manufacturing systems. The distinction matters because traditional fermentation changes the substrate, while precision fermentation uses microbes to create an entirely new product.

The proteins produced through precision fermentation are molecularly identical to animal-derived dairy proteins - same amino acids, same structure, same taste. Your body literally cannot tell the difference.

The technology produces proteins that behave exactly like their animal-derived counterparts because, at the molecular level, they are identical. Same amino acid sequence, same folding structure, same functional properties. Which means they melt, stretch, foam, and taste like conventional dairy proteins. A cheese made with precision fermentation whey will brown and bubble on pizza just like mozzarella always has.

This isn't the first time a transformative food technology has disrupted an established agricultural system. When margarine was invented in 1869, the dairy industry fought back viciously. Some U.S. states banned margarine outright, others required it to be dyed pink to make it look unappetizing, and dairy lobbies pushed through federal laws imposing punitive taxes. The threat was existential: if people could get butter-like products from vegetable oils, what would happen to dairy farmers?

The dairy industry survived, of course. Margarine carved out its own market segment, but butter remained prestigious, preferred by serious cooks, and culturally significant. The two products coexisted, though not without decades of bitter conflict and regulatory battles that, in hindsight, look absurd.

A similar pattern emerged with plant-based milk alternatives. When soy, almond, and oat milk gained popularity over the past two decades, dairy producers fought for labeling restrictions, arguing that calling these beverages "milk" misled consumers. Yet conventional dairy consumption did decline - U.S. per capita consumption dropped by nearly 40% since 1975 - but the industry adapted through consolidation, premium products, and export markets.

What made those disruptions survivable was that the alternatives were clearly different products. Margarine doesn't taste exactly like butter. Oat milk has a distinct flavor profile from cow's milk. Consumers chose them for different reasons: cost, health concerns, environmental values, or dietary restrictions. There was functional differentiation.

"Precision fermentation proteins collapse the distinction between conventional and alternative dairy. When the molecule is identical, when cheese tastes indistinguishable from conventional cheese, when there's no functional difference whatsoever, the disruption could be more complete."

- Analysis from consumer acceptance research

The historical lesson suggests the dairy industry will fight hard - and this time, the alternative isn't clearly inferior or different enough to occupy a separate niche.

Inside a fermentation facility, the process mirrors industrial biotechnology that's been producing insulin, rennet, and enzymes for decades. The modified microorganisms - usually yeast strains like Saccharomyces cerevisiae or bacteria like E. coli - are cultivated in large stainless steel bioreactors. These tanks maintain precisely controlled temperature, pH, oxygen levels, and nutrient concentrations optimized for protein production.

The microbes consume sugar feedstocks (often from corn or sugarcane) and secrete the target protein into the surrounding liquid medium. This is where precision fermentation differs fundamentally from cellular agriculture, which grows actual animal cells. Precision fermentation uses microbes as biochemical factories; cellular agriculture recreates animal tissue. The former is technologically simpler and further along the commercialization curve.

After the fermentation cycle completes - typically 48 to 72 hours - the microbial biomass is separated from the liquid containing the protein. This happens through filtration, centrifugation, or a combination of separation techniques. The protein is then purified, concentrated, and spray-dried into a powder that can be shipped to food manufacturers.

One crucial aspect: the host microorganism is removed completely. When Perfect Day faced a lawsuit alleging their product contained fungal proteins from the production organism, the company maintained that the host microbe is "completely filtered out" of the final product. Independent testing by the Food Allergy Research & Resource Program (FARRP) determined that residual fungal proteins in the samples posed no allergenicity concerns. The FDA issued a "no questions" letter in 2020 affirming the ingredient's GRAS (Generally Recognized as Safe) status.

The purity question matters because it addresses both safety and the fundamental claim these companies make: they're producing real dairy proteins, not fungal proteins that happen to be similar. The molecular identity is the entire value proposition.

Perfect Day has become the most visible player in precision fermentation dairy, but they represent just one approach to commercialization. Rather than selling directly to consumers, Perfect Day operates as an ingredient supplier, licensing their technology and proteins to established food companies. Their partnership with Unilever resulted in a lactose-free frozen dessert under the Breyers brand. They've also worked with The Urgent Company to create Brave Robot ice cream.

This B2B model makes strategic sense. Perfect Day can focus on optimizing the biotechnology while leveraging the distribution networks, marketing expertise, and consumer trust that established food companies have built over decades. It's less capital-intensive than building an entirely new consumer brand from scratch.

Other companies are taking different approaches. Formo, a German startup, is developing precision fermentation cheese proteins with plans to launch in European markets. Change Foods, based in Australia and the United States, is targeting the cheese category specifically, working on casein proteins that can replicate traditional cheese-making processes. Imagindairy, an Israeli company, focuses on producing whey proteins and is pursuing partnerships with dairy manufacturers.

Then there's Remilk, another Israeli company that's taken a more integrated approach, planning to produce finished dairy products rather than just supplying ingredients. They're constructing large-scale production facilities in Denmark with the capacity to produce thousands of tons of protein annually.

The market projections are staggering, though they should be taken with appropriate skepticism. Various market research firms estimate the precision fermentation market could reach $34 billion by 2031, growing at a 40% compound annual growth rate. Those figures likely reflect aspirational best-case scenarios rather than sober forecasts, but they indicate where investment capital is flowing.

What's more telling than the projections is which established food companies are paying attention. Bel Group, the French cheese giant behind Laughing Cow and Babybel, has been actively investing in and partnering with precision fermentation startups. Their venture chief Caroline Sorlin has publicly discussed the technology's potential to complement their existing product lines. When century-old dairy companies start hedging their bets, the technology has crossed from speculative to strategic.

The environmental case for precision fermentation rests on straightforward physics and biology. Conventional dairy production requires growing feed crops (which need land, water, and fertilizer), raising cattle (which consume that feed inefficiently), managing waste, and processing milk. Each step consumes resources and generates emissions.

Precision fermentation collapses that chain. Microbes convert sugar to protein with far greater efficiency than a cow converts grass and grain to milk. A dairy cow needs about 10 pounds of feed to produce 1 pound of milk protein. Yeast can theoretically achieve conversion ratios several times better, though real-world production facilities haven't yet reached that theoretical maximum.

Studies suggest precision fermentation could reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 85-95% compared to conventional dairy, primarily by eliminating enteric methane from cow digestion - a potent greenhouse gas contributing significantly to agriculture's climate impact.

Studies suggest precision fermentation could reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 85-95% compared to conventional dairy, primarily because it eliminates enteric methane from cow digestion - a potent greenhouse gas that contributes significantly to agriculture's climate impact. Land use could decrease by up to 95%, because you don't need pastures or feed crop acreage. Water consumption might drop by 90% or more, since fermentation tanks use vastly less water than what's required for dairy operations when you account for animal drinking water, cleaning, and irrigation for feed crops.

Those figures come mostly from life cycle assessments commissioned by companies in the sector or advocacy organizations like the Good Food Institute, so they deserve scrutiny. Independent academic assessments are still emerging. One critical variable is the energy source powering the fermentation facilities. If they run on renewable energy, the environmental benefits are dramatic. If they're powered by coal, the equation changes significantly.

Another consideration: the sugar feedstock source matters. If precision fermentation scales up dramatically, will it drive demand for corn syrup or sugarcane, potentially incentivizing land conversion or monoculture farming? The most sustainable scenarios involve using waste sugars from agricultural or forestry operations, but those feedstocks are limited. As the industry scales, feedstock sourcing becomes a environmental determinant just as significant as the efficiency of the fermentation process itself.

Still, even accounting for uncertainties, the resource efficiency of using microbes rather than large mammals to produce proteins seems likely to offer genuine environmental advantages. Cows are remarkable animals, but they're thermodynamically terrible at protein production because so much of what they consume goes to maintaining body heat, moving around, and other metabolic functions unrelated to milk synthesis.

Because the proteins are molecularly identical to those from cow's milk, they have the same nutritional profile. Beta-lactoglobulin made through fermentation contains the same amino acids, in the same sequence, as beta-lactoglobulin from a cow. Your body can't tell the difference during digestion.

This means precision fermentation proteins aren't suitable for people with genuine milk protein allergies. If you're allergic to casein, precision fermentation casein will trigger the same immune response. The technology removes lactose and can eliminate cholesterol, but it doesn't solve protein allergies.

From a food safety perspective, precision fermentation may offer advantages. The controlled fermentation environment reduces contamination risks compared to dairy farms, where milk can be exposed to various pathogens. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) released a report examining food safety aspects of precision fermentation, concluding that the technology poses no inherently greater risks than conventional food production methods, provided good manufacturing practices are followed.

Regulatory agencies have been evaluating these products using existing frameworks for food ingredients. In the United States, several precision fermentation proteins have received GRAS designation from the FDA. In Singapore, regulatory approval came relatively quickly, allowing precision fermentation products to reach consumers. Europe has moved more cautiously, with precision fermentation ingredients subject to the European Union's novel food regulations, which require extensive safety data and explicit authorization before products can be marketed.

The EFSA approval process has historically been slower than in other jurisdictions, though recent initiatives aim to streamline timelines for novel foods. Still, navigating the patchwork of international regulations represents a significant barrier to rapid global scaling. What's approved in the U.S. may take years to clear regulatory hurdles in Europe or other markets.

"When people understand the process - particularly that it's similar to how insulin and other medicines are produced - safety concerns diminish. Calling it 'fermentation' resonates more positively than 'genetic engineering,' even though both descriptions are accurate."

- Consumer research findings from five European countries and the United States

Consumer research on safety perceptions reveals interesting patterns. Studies conducted across France, Germany, Spain, the UK, and the United States show that when people understand the process - particularly that it's similar to how insulin and other medicines are produced - safety concerns diminish. Calling it "fermentation" resonates more positively than "genetic engineering," even though both descriptions are accurate. Language matters in shaping public acceptance.

Here's where optimism meets physics. For precision fermentation to truly disrupt conventional dairy, it needs to achieve cost parity or better. Currently, it's significantly more expensive.

Industry insiders estimate that precision fermentation proteins cost anywhere from 5 to 20 times more to produce than equivalent dairy proteins, depending on the specific protein and production scale. Perfect Day reportedly achieved production costs around $20 per kilogram for whey protein, compared to roughly $5-8 per kilogram for conventional whey protein. That gap has been narrowing as production scales up and processes optimize, but it remains substantial.

Several factors determine whether costs will continue falling. Scale is obvious - larger fermentation facilities spread fixed costs across more output. Strain improvement matters tremendously; engineering microbes that produce more protein per fermentation cycle directly improves economics. Feedstock costs are critical since sugar inputs represent a significant portion of operating expenses. And downstream processing - the filtration, purification, and drying steps - can account for 50% or more of total production costs.

Some analysts believe precision fermentation can achieve cost parity with conventional dairy within 5-10 years if the industry follows a trajectory similar to solar panels or LED lights, where production costs fell exponentially as manufacturing scaled and technology improved. Others are more skeptical, pointing out that fermentation is fundamentally different from electronics manufacturing. Biological systems have inherent variability and limitations that don't respond to scaling the same way semiconductor production does.

One potentially powerful economic lever is co-products. If fermentation facilities can produce multiple valuable outputs from the same feedstock, the economics improve dramatically. Some companies are exploring producing both proteins and fats, or proteins and high-value enzymes, from integrated processes.

What seems likely is that precision fermentation proteins will first become competitive in premium markets and applications where conventional dairy proteins are already expensive or where functional advantages justify a price premium. Whey protein isolate for sports nutrition, specialty cheese proteins, or infant formula ingredients might offer better initial opportunities than commodity markets like fluid milk.

All the technology and economics become irrelevant if people won't eat the products. Consumer acceptance research reveals a complicated picture.

Blind taste tests generally show that products made with precision fermentation proteins are indistinguishable from conventional dairy. Perfect Day's ice cream, when tested against premium conventional ice cream in controlled sensory evaluations, scored similarly on flavor, texture, and overall liking. This makes sense given the molecular identity of the proteins.

Where things get complicated is when consumers know what they're eating. Studies show that acceptance varies significantly by country and demographic group. Younger consumers, urban dwellers, and people already purchasing plant-based alternatives tend to be more open to precision fermentation products. Older consumers, rural populations, and those who identify strongly with traditional agriculture are more skeptical.

Messaging matters enormously. When precision fermentation is framed as "animal-free dairy" or "made through fermentation like beer or yogurt," acceptance increases. When it's described as "genetically engineered proteins" or "made with GMO yeast," acceptance drops, particularly in Europe. The labels "cell-free," "brewed," and "cultured" all tested better in consumer research than "synthetic" or "lab-grown."

Cultural context shapes reception too. In Singapore and Israel, where food security concerns are acute due to limited agricultural land, precision fermentation foods have been embraced more readily. In France, where dairy heritage carries deep cultural significance and skepticism of food technology runs high, the resistance is stronger.

There's also a values alignment question. Some people adopt plant-based diets for ethical reasons related to animal welfare. Precision fermentation offers them access to the exact dairy products they've been avoiding, without the animal farming they object to. For these consumers, the technology resolves a genuine dilemma. Others choose plant-based for environmental reasons, and precision fermentation delivers dramatic sustainability improvements compared to conventional dairy.

In blind taste tests, products made with precision fermentation proteins are indistinguishable from conventional dairy. The challenge isn't flavor - it's convincing consumers to try them in the first place.

But not everyone sees it that way. Some organic and anti-GMO advocacy groups fundamentally oppose genetic engineering in food production, regardless of specific applications or benefits. For them, precision fermentation represents an unwelcome industrialization of food systems, a doubling down on technological solutions rather than returning to what they view as more natural farming methods. This opposition has manifested in lawsuits, advocacy campaigns, and lobbying for strict labeling requirements.

If precision fermentation scales successfully, the implications for conventional dairy farming are profound. Dairy farms already operate on thin margins in many regions, kept viable through subsidies, cooperatives, and vertically integrated supply chains. A technology that produces identical proteins at lower cost could be economically devastating.

The scale of potential disruption depends on how quickly and completely precision fermentation can substitute for conventional dairy across different applications. Fluid milk might be harder to replace than protein concentrates. Cultural attachment to traditional dairy varies by product category and geography. But some projections suggest that by 2035, precision fermentation could capture significant market share in key dairy protein segments, particularly in regions where environmental regulations make conventional dairy increasingly expensive.

Rural communities dependent on dairy farming face a dilemma similar to what coal regions experienced with renewable energy. The economic transition could be wrenching. Dairy farming employs millions globally and provides livelihoods in regions with limited alternative economic opportunities. If that industry contracts rapidly, those communities need support - retraining programs, economic development initiatives, transition assistance. History shows that technological disruptions that benefit society overall can devastate specific communities if the transition isn't managed thoughtfully.

One possible future involves conventional dairy farms pivoting to producing feedstocks for precision fermentation, growing sugar crops or processing agricultural waste into fermentation inputs. Another possibility is that conventional dairy finds a sustainable niche as a premium, craft product emphasizing terroir, heritage breeds, and traditional methods - similar to how craft brewing coexists with industrial beer production.

What seems unlikely is that conventional dairy continues operating exactly as it has. The economic and environmental pressures were building before precision fermentation emerged. This technology accelerates trends already in motion.

Different regions are positioning themselves distinctly in the precision fermentation landscape. The United States has taken a relatively permissive regulatory approach, treating precision fermentation proteins as ingredients subject to existing food safety frameworks. This has allowed faster commercialization and attracted significant venture capital investment. American startups dominate the sector's early stages.

Israel has become a hub for food technology innovation, including precision fermentation, driven partly by food security concerns in a region with limited agricultural resources and geopolitical instability. The Israeli government has actively supported biotech food companies through grants and infrastructure investment.

Europe presents a more fragmented picture. Consumer skepticism toward genetic engineering is higher in many European countries, and regulatory requirements are more stringent. However, some European nations, particularly in Scandinavia, are showing more openness. Companies are establishing production facilities in Denmark and the Netherlands to serve the European market once regulatory approvals come through.

Singapore has positioned itself as a testbed for food technology, offering streamlined regulatory approval and attracting companies to launch products there first. For a city-state that imports 90% of its food, precision fermentation represents a strategic opportunity to enhance food security. Singapore's approach could serve as a model for other import-dependent nations.

China's engagement with precision fermentation remains relatively opaque but potentially significant. Chinese companies and research institutions are actively working on similar technologies, and the government has identified biotechnology as a strategic priority. If China's enormous market opens to these products, the scale dynamics could shift dramatically.

International cooperation on regulatory standards could accelerate adoption, reducing the duplicative costs of seeking approval in each market independently. Trade associations like Food Fermentation Europe are working to establish common definitions and safety protocols that could facilitate harmonized regulations.

The precision fermentation industry creates demand for a specific skill mix: molecular biology, fermentation science, food science, bioprocess engineering, and regulatory affairs expertise. Universities are beginning to develop specialized programs combining microbiology, chemical engineering, and food technology to train the scientists and engineers this sector needs.

For workers currently in conventional dairy, the transition is less straightforward. Dairy farming skills don't directly transfer to fermentation facilities. However, food processing, quality control, and supply chain management skills remain relevant. And someone needs to grow the feedstock crops that fuel fermentation tanks.

Investors trying to evaluate this space face genuine uncertainty. The technology works at lab and pilot scale. The question is how efficiently it scales, how quickly costs fall, and how consumers respond. Early-stage startups carry substantial risk. Established food companies integrating precision fermentation into existing product lines represent a more conservative bet.

Consumers who want to prepare for this shift can start engaging with the products now available. Perfect Day's partnerships have resulted in ice cream products available in several markets. Trying these products, understanding the labeling, and developing informed opinions helps shape how this technology evolves. Consumer preferences, expressed through purchasing decisions, will ultimately determine which applications succeed.

Policymakers face complex choices. Supporting innovation and sustainability suggests enabling precision fermentation's growth. Protecting existing agricultural communities and preserving food culture suggests caution. Threading that needle requires policies that encourage technological progress while supporting communities through economic transition.

There's a deeper transformation happening here that extends beyond dairy proteins. Precision fermentation represents a shift from agriculture - growing things - to programming biology to manufacture things. Once you've turned a food component into a genetic sequence that can be expressed in microbes, you've essentially turned it into code that can be optimized, scaled, and iterated like software.

This has implications far beyond dairy. Companies are pursuing precision fermentation for egg proteins, collagen, fats, vitamins, and enzymes. The patent landscape around precision fermentation in food and beverage has exploded, with thousands of applications filed in recent years covering different production organisms, protein types, and manufacturing processes.

"We're witnessing the beginning of a broader transformation in how humanity produces food. Not replacing all agriculture, but creating a new production paradigm that exists alongside traditional farming, plant-based alternatives, and cellular agriculture."

- Food technology analysts

If this approach proves economically viable at scale, we're witnessing the beginning of a broader transformation in how humanity produces food. Not replacing all agriculture, but creating a new production paradigm that exists alongside traditional farming, plant-based alternatives, and cellular agriculture. A portfolio of food production methods, each optimized for different applications.

The dairy industry took 10,000 years to develop from the first domestication of cattle. Precision fermentation dairy went from concept to commercial products in about 15 years. That acceleration reflects the power of biotechnology, but also the urgency of environmental challenges that make the current food system unsustainable.

Whether precision fermentation lives up to its promise depends on solving technical challenges, navigating regulatory complexity, achieving cost competitiveness, and earning consumer trust. Those are not small hurdles. But the proteins being produced in fermentation tanks today aren't prototypes anymore. They're real products, with real companies behind them, entering real supply chains. The revolution isn't coming - it's quietly brewing right now.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

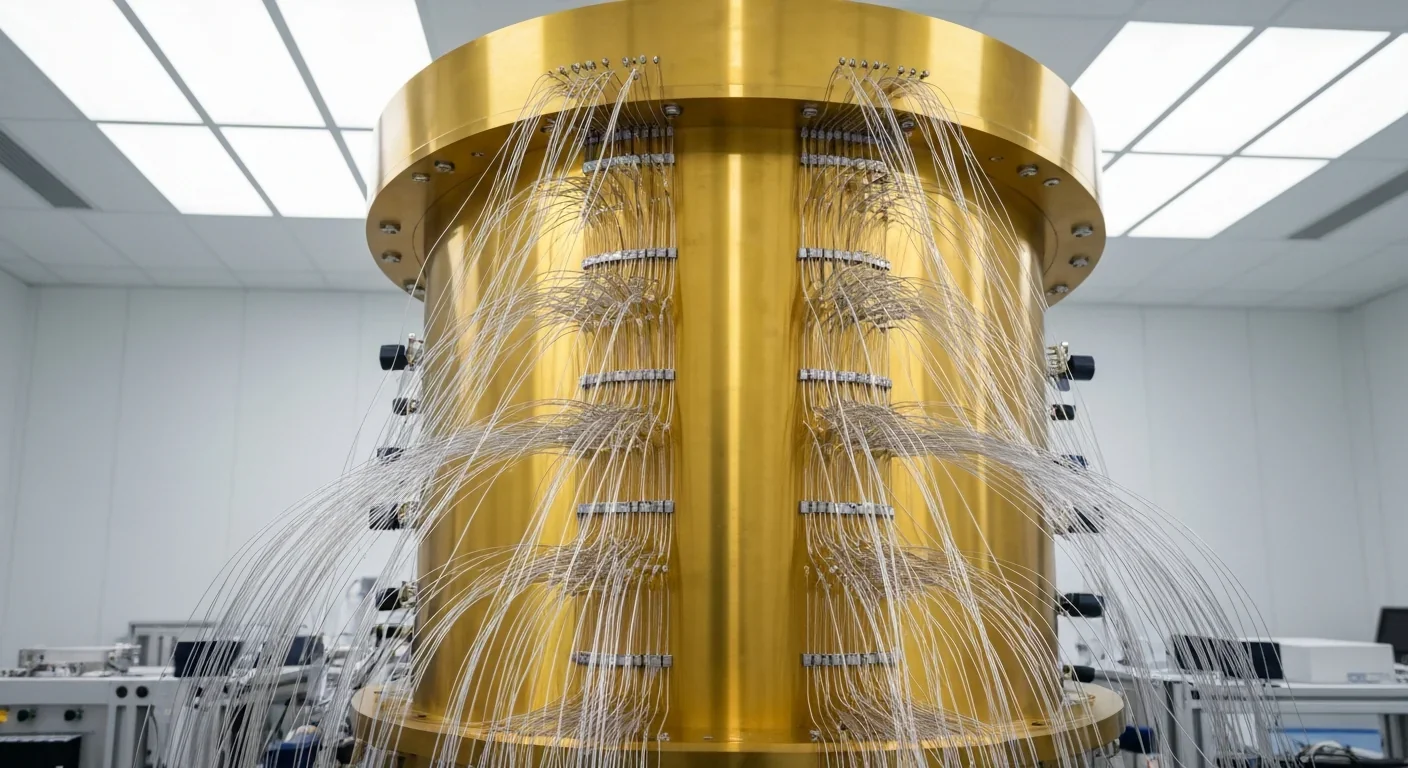

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.