AI Cameras Save Sea Turtles in Fishing Nets

TL;DR: RNA interference technology is revolutionizing agriculture by enabling precise pest control through molecular sprays that silence specific genes in target organisms without genetic modification, chemical toxicity, or environmental persistence - offering a sustainable path forward for global food production.

By 2034, a $227 million industry could fundamentally change how humanity grows food. Not through genetic engineering or new chemicals, but through something far more elegant: teaching plants to whisper instructions that only their enemies can hear.

RNA interference technology is moving from laboratory curiosity to commercial reality, and it's forcing us to rethink everything we thought we knew about protecting crops. Unlike the contentious debates around GMOs or the mounting concerns about chemical pesticides, this approach offers something different - precision without permanence, targeting without toxicity, and protection without genetic modification.

The implications stretch far beyond agriculture. This technology represents a new paradigm in how we interact with living systems, one that could reshape food security, environmental health, and the economics of farming for the next century.

To understand why this matters, you need to grasp what makes RNA interference fundamentally different from everything that came before it.

Every living cell contains genetic instructions written in DNA, transcribed into messenger RNA, and translated into proteins. RNA interference hijacks this system by introducing double-stranded RNA molecules that match specific genes in target pests. When insects eat plants treated with these molecules, their cellular machinery mistakes the dsRNA for viral infection and activates an ancient defense mechanism.

The enzyme Dicer chops the double-stranded RNA into small interfering RNAs (siRNA), about 21-23 nucleotides long. These fragments are loaded into a molecular complex called RISC - the RNA-induced silencing complex - which uses them as a guide to find and destroy matching messenger RNA sequences. No messenger RNA means no protein production. And when those proteins are essential for survival - digestive enzymes, developmental regulators, cellular maintenance proteins - the pest simply stops functioning.

A 21-nucleotide RNA sequence creates roughly one trillion possible combinations. This extraordinary specificity means RNA interference can target a single pest species while leaving every other organism in the ecosystem completely unharmed.

Here's what makes this revolutionary: the specificity is exquisite. A 21-nucleotide sequence creates roughly 10^12 possible combinations. Design your dsRNA to match a gene sequence unique to Colorado potato beetles, and it will silence that gene in Colorado potato beetles. Honeybees, ladybugs, earthworms, and humans eating the potato? Their genes don't match, so the RNA has nowhere to bind. The molecule passes through their systems and degrades naturally within days.

This isn't theory. GreenLight Biosciences' Calantha spray, approved by the EPA in 2024, targets the Colorado potato beetle with this exact mechanism. Farmers spray it on potato plants just like conventional pesticides, but the active ingredient is RNA, not synthetic chemicals. The beetle larvae eat treated leaves, their cellular machinery gets hijacked, essential proteins stop being made, and the pest dies - while everything else in the field continues thriving.

Agriculture has always been a race between human ingenuity and natural selection. For millennia, we controlled pests through crop rotation, companion planting, and accepting significant losses. Then came the chemical revolution.

The pesticide era began with real promise. DDT virtually eliminated malaria-carrying mosquitoes in wealthy nations. Organophosphates gave farmers unprecedented control over insect populations. For a few decades in the mid-20th century, it seemed like chemistry had solved the pest problem permanently.

But evolution is relentless. Pests developed resistance. Helicoverpa armigera, the cotton bollworm, now shrugs off many insecticides that once killed it reliably. Meanwhile, we discovered those "safe" chemicals accumulating in ecosystems, disrupting hormone systems, killing beneficial insects along with pests, and leaving residues that persist for decades.

The genetic engineering wave promised a better way. Instead of spraying chemicals, why not give plants their own defenses? Bt corn, engineered to produce insecticidal proteins from Bacillus thuringiensis bacteria, became one of agriculture's success stories. The European corn borer, once a devastating pest, met its match.

But GMO crops came with their own complications. The genetic modifications are permanent, passed to every seed. Regulatory approval takes years and costs tens of millions of dollars. Public acceptance varies dramatically across cultures - embraced in the Americas, heavily restricted in Europe, debated everywhere. And pests are already evolving resistance to Bt proteins through generations of selection pressure.

RNAi technology emerged from basic research that won the 2006 Nobel Prize. Scientists studying how cells regulate genes in the roundworm C. elegans stumbled onto a fundamental biological mechanism. Fire and Mello discovered that introducing double-stranded RNA could silence specific genes with startling precision.

The agricultural potential became obvious immediately. If you could design RNA molecules to silence pest genes, you'd have the targeting precision of GMOs without permanent genetic modification. The challenge was delivery - how do you get fragile RNA molecules into pest cells when they degrade in sunlight, break down in soil, and get destroyed by plant enzymes?

That problem occupied researchers for nearly two decades. The first patents appeared in 2003, primarily from Monsanto and other agricultural giants exploring transgenic approaches - plants genetically engineered to produce the dsRNA internally. Patent applications peaked at 392 in 2011, then plateaued as companies shifted focus from research to commercialization.

The breakthrough came from nanotechnology. Researchers discovered that encapsulating dsRNA in protective carriers - chitosan nanoparticles, layered double hydroxide clay, lipid vesicles - dramatically extended stability. A spray that might degrade in hours could now persist for 10-14 days on leaf surfaces, protected from UV radiation and nuclease enzymes.

Today's RNA crop protection follows two distinct strategies, each with its own advantages and limitations.

The transgenic approach creates plants that continuously produce dsRNA targeting specific pests. Bayer's SmartStax Pro corn, approved by the EPA in 2023, combines traditional Bt proteins with RNA interference against the western corn rootworm. The corn produces dsRNA molecules that target the DvSnf7 gene, essential for cellular protein sorting in the rootworm. Larvae feeding on roots ingest the dsRNA, their cells can't sort proteins properly, and they die.

This works brilliantly for major commodity crops where seed development costs can be amortized across millions of acres. But it's still genetic modification, requiring the full regulatory pathway and facing the same public acceptance challenges as other GMO crops.

The spray approach avoids genetic modification entirely. Farmers apply dsRNA formulations just like conventional pesticides - through standard spraying equipment, on existing crop varieties, without changing the plant's genome. The RNA is manufactured through fermentation processes, similar to brewing beer or producing insulin, then formulated with protective carriers.

"RNA interference pesticides offer unprecedented precision in targeting pests while sparing beneficial organisms and minimizing environmental harm."

- BIS Research, Global RNAi Pesticides Market Analysis

This is where the technology gets really interesting for global adoption. Calantha, that Colorado potato beetle spray, represents the first commercial realization of this approach. GreenLight Biosciences produces the dsRNA using a cell-free synthesis platform - no bacteria or yeast required, just the enzymatic machinery for RNA production in a controlled environment. This dramatically reduces production costs and regulatory complexity compared to transgenic approaches.

The spray method offers something else transgenic crops can't: flexibility. Farmers can choose when and where to apply it, adjust to changing pest pressures, and switch between different RNA formulations for different pests - all with crops they're already growing.

For any agricultural technology to transform farming, it has to make economic sense to the people actually in the fields.

The global RNA pesticides market started from essentially zero in 2020. By 2024, it reached $44.98 million, projected to grow at 17.6% annually to hit $227.54 million by 2034. That's still small compared to the $70 billion conventional pesticide industry, but the trajectory matters more than current size.

Consider what's driving this growth. In Asia-Pacific, where intensive agriculture faces severe pest pressures and growing concerns about pesticide residues, the regional market hit $5.5 million in 2024, expected to reach $22 million by 2034. Europe, despite stringent GMO regulations, embraced RNA sprays precisely because they're not genetic modification - the EU market reached $10.5 million in 2024, projected to grow to $49.1 million by 2034.

The cost structure is shifting in farmers' favor. Early production methods made dsRNA expensive - roughly $15,000 per kilogram of purified molecule. But cell-free synthesis platforms and fermentation scale-up are driving prices down. GreenLight Biosciences claims their platform can produce dsRNA at costs competitive with synthetic pesticides for high-value crops like potatoes, tomatoes, and specialty vegetables.

Application rates matter enormously. Because RNA interference is so specific, you need tiny amounts of active ingredient - often measured in grams per hectare rather than kilograms. One liter of concentrated RNA spray might treat several acres. The protective nanoparticle formulations mean fewer applications per season since the dsRNA persists longer on plant surfaces.

For potato farmers dealing with Colorado potato beetles, the calculation looks something like this: conventional insecticides require 3-5 applications per season at $30-50 per acre. Calantha treatments currently cost more per application but require only 2-3 treatments, and they don't kill beneficial insects that help control other pests. The economic break-even exists today for some crops and regions; as production scales, it shifts in RNA's favor.

There's another economic factor that's harder to quantify but increasingly important: market access. European and Asian consumers pay premiums for produce grown without synthetic pesticides. Several major retailers are reducing or eliminating products grown with neonicotinoids and other controversial chemicals. RNA-based crop protection offers a path to premium prices without sacrificing yields.

Every new agricultural technology faces the same question: what are we trading for this benefit?

With chemical pesticides, the trade-offs became painfully clear over decades. Organophosphates kill not just pests but beneficial insects, birds, and aquatic organisms. Neonicotinoids devastate pollinator populations. Herbicide residues accumulate in water systems. The collateral damage eventually caught up with the benefits.

RNA interference offers a fundamentally different safety profile because of how it works at the molecular level.

First, the specificity. A dsRNA molecule designed to silence a gene in Colorado potato beetles won't affect honeybees because honeybees don't have that gene sequence. This isn't about dose or exposure levels - it's about matching. If the genetic sequence doesn't exist in an organism, the RNA literally has nothing to bind to. It's like having a key that only fits one lock in the entire ecosystem.

This has been tested extensively. Studies with non-target insects show no effects even at exposure levels far exceeding what would occur in fields. Predatory insects feeding on targeted pests remain unharmed. Pollinators visiting treated plants show no impacts on survival or reproduction. The molecular specificity translates directly to ecological selectivity.

RNA molecules sprayed on crops break down within days to weeks, degrading into nucleotides that plants and soil microbes absorb as nutrients. There's no long-term accumulation, no persistent residues, no building up through food chains.

Second, the degradation. RNA molecules are inherently unstable - one reason living cells constantly produce them. Outside of cells, they break down rapidly through hydrolysis and enzyme activity. Even with protective nanoparticle coatings, sprayed dsRNA degrades within days to weeks, breaking down into component nucleotides that plants and soil microbes absorb as nutrients. There's no long-term accumulation, no persistent residues, no building up through food chains.

For humans eating treated crops, the safety case is straightforward. We consume massive amounts of plant RNA in every meal - every fruit, vegetable, and grain contains millions of RNA molecules. Our digestive systems break them down immediately. The sequence specificity that targets pest genes has no corresponding targets in human biology. The EPA's safety assessment for Calantha found no toxicity, no allergenicity, and no reason for concern about dietary exposure.

The environmental risk assessment is more nuanced but similarly favorable. Regulatory frameworks initially developed for GMO crops can be adapted for RNA products, but the assessment is actually simpler in some ways. There's no gene flow to worry about since nothing is genetically modified. The primary questions are: does it affect non-target species (evidence says no), does it persist in the environment (it degrades rapidly), and could it create resistant pest populations (possible but manageable through rotation)?

That last point deserves attention. Pests can evolve resistance to anything, including RNA interference. Insects with mutations in the target gene sequence might survive treatment. But resistance development appears slower with RNAi than with chemical pesticides or Bt proteins because you can target multiple essential genes simultaneously. A pest would need multiple coordinated mutations to resist a cocktail of dsRNAs targeting different genes - a much higher evolutionary barrier.

The current generation of RNA crop protection is impressive, but it's really just the beginning of what's possible.

Right now, commercial products target mainly insect pests - corn rootworms, potato beetles, cotton bollworms. But the technology works for any organism whose cells process RNA, which means essentially all agricultural pests.

Weed management is already in development. GreenLight Biosciences announced breakthrough progress on RNA herbicides that silence genes essential for weed growth while leaving crops unharmed. This addresses one of agriculture's most pressing challenges: weeds that have evolved resistance to glyphosate and other herbicides. An RNA-based approach could target weeds specifically without the broad-spectrum effects of chemical herbicides.

Fungal diseases respond to RNA interference targeting genes essential for infection and spread. Research on Fusarium, Botrytis, and other major pathogens shows that spraying dsRNA against fungal genes can prevent or halt infections with a specificity impossible for chemical fungicides. This matters enormously for crops like grapes, tomatoes, and wheat where fungal diseases cause billions in annual losses.

Viral plant diseases are notoriously difficult to control - no chemical can kill a virus without killing the plant. But RNA interference naturally evolved to fight viruses. Treating plants with dsRNA targeting viral genes can confer resistance to multiple virus families, protecting crops from infections that currently have no other treatment.

Nematodes, microscopic worms that devastate root systems, could be controlled through RNA silencing of genes essential for their development. Tropic Biosciences and other biotech companies are developing dsRNA formulations targeting plant-parasitic nematodes, potentially eliminating the need for toxic soil fumigants.

"The next decade will be pivotal - beyond just RNAi technology, it's a cornerstone of climate-resilient, precision agriculture."

- BIS Research Editorial on Agricultural Innovation

The delivery mechanisms are also evolving. Current nanoparticle formulations protect dsRNA for days to weeks, but researchers are developing smart nanosensors that could monitor RNA persistence in real-time, informing farmers exactly when reapplication is needed. Integration with precision agriculture systems could enable variable-rate application, spraying only where pest pressure exists.

Perhaps most intriguingly, gene editing meets RNA interference in next-generation approaches. Rather than engineering plants to produce dsRNA continuously, researchers are using CRISPR to insert inducible RNA sequences - genetic switches that activate only under specific conditions like pest attack. This could provide the benefits of transgenic approaches with greater control and flexibility.

Technologies don't exist in isolation - they succeed or fail based on how different societies adopt them.

In North America, the regulatory pathway is established and functioning. EPA approval of SmartStax Pro and Calantha demonstrates that RNA-based products can navigate the regulatory system, though each new target pest or crop requires separate evaluation. The USDA treats non-transgenic RNA applications differently from GMOs, which accelerates approval for spray-based products.

Europe's response reveals how RNA technology could bypass some of the GMO controversies that have frustrated agricultural innovation for decades. The EU's strict regulations on genetic modification don't apply to external RNA applications since they don't modify plant genomes. This creates an unusual situation where European farmers might adopt RNA sprays faster than their American counterparts for some crops, particularly in organic and sustainable agriculture systems seeking alternatives to chemical pesticides.

Asia faces perhaps the most urgent need. China, India, and Southeast Asian nations support massive populations on intensive agriculture that relies heavily on chemical pesticides. Pest resistance and environmental degradation are accelerating problems. Government research programs in China and India are actively developing RNA crop protection technologies, with significant state investment and faster regulatory pathways than Western nations.

Africa and Latin America represent different challenges and opportunities. Small-holder farmers dominating agriculture in these regions need affordable, accessible technologies that don't require expensive infrastructure. If RNA production costs continue declining and application methods remain compatible with existing spraying equipment, the technology could address pest problems without the capital requirements of transgenic seed systems.

But social acceptance varies dramatically. Studies of public perception show that many consumers don't distinguish between genetic modification and RNA sprays, lumping all "genetic technologies" together as concerning. Others view RNA as categorically different - no different from organic sprays like Bt bacteria, just more precisely targeted. This perception gap will influence adoption rates as much as scientific evidence.

The patent landscape complicates global access. Bayer holds 143 of the 275 registered patent families in RNA crop protection, with smaller shares for other agricultural giants. This concentration of intellectual property could limit access in developing nations unless licensing arrangements or humanitarian exemptions are established. The history of pharmaceutical patents provides cautionary lessons about how intellectual property can constrain global benefit from breakthrough technologies.

Agricultural transformation rarely announces itself with fanfare. It emerges gradually as farmers make pragmatic decisions about what works in their fields and what doesn't.

For farmers and agricultural professionals, the immediate question is timing. Early adopters of Calantha and similar products are testing not just efficacy but practical integration - how RNA sprays fit into existing integrated pest management programs, whether they play well with biological control agents, what happens to pest populations over multiple growing seasons. These field experiences will determine adoption rates far more than laboratory data.

The cost-benefit calculation will shift year by year. As production scales up and competition increases, RNA spray costs will decline. As regulatory approvals accumulate for more pests and crops, the range of applications will expand. As pest resistance to conventional pesticides worsens, the relative value of RNA precision will increase. At some point in the next 5-10 years, for certain crops in certain regions, RNA-based crop protection will become the obviously superior choice.

For policymakers and regulators, the challenge is creating frameworks that ensure safety without stifling innovation. The current approach of treating each RNA product separately - new evaluations for each pest-crop combination - makes sense for initial approvals but could become a bottleneck. More sophisticated regulatory science that recognizes common principles of RNA safety while maintaining appropriate oversight will be necessary.

For the agricultural industry, investment decisions made now will shape who benefits from this transition. Traditional pesticide manufacturers can pivot to RNA production or risk obsolescence. Biotechnology startups are racing to develop platforms that reduce production costs and expand applications. The companies that crack the manufacturing challenge - making high-quality dsRNA cheaply and at scale - will capture extraordinary value.

For consumers and environmental advocates, RNA technology offers a rare alignment of interests. Farmers get effective pest control. The environment gets dramatically reduced chemical loads. Food safety improves through lower pesticide residues. Beneficial insects, pollinators, and ecosystem health are protected. This convergence of benefits suggests RNA crop protection could achieve something few agricultural technologies manage: broad consensus support.

The trajectory is clear even if the timeline remains uncertain. Over 180 peer-reviewed publications and nearly 300 patent families document intensive development across dozens of pest species. Multiple products are now commercially approved. Production costs are declining. Regulatory pathways exist and function. Market projections show consistent growth.

But perhaps the most telling indicator is how RNA technology fits into broader agricultural transitions. Climate change is intensifying pest pressures as insects expand their ranges and viral diseases spread to new regions. Chemical resistance is accelerating across pest spectra. Consumer preferences are shifting toward sustainably produced food. These converging pressures create exactly the conditions where precision pest control through molecular mechanisms becomes not just attractive but necessary.

What happens when precision biological control becomes the norm rather than the exception?

For individuals working in agriculture or related fields, developing literacy in molecular biology and biotechnology shifts from optional to essential. Understanding the difference between genetic modification and RNA interference, knowing how to evaluate evidence for efficacy and safety, being able to explain these distinctions to stakeholders - these become core competencies.

For agricultural education and extension services, curriculum updates can't wait for technologies to become mainstream. Today's students need to understand RNA interference mechanisms now, so they're prepared to advise farmers on optimal use when adoption accelerates. The successful extension agents of the next decade will be those who can bridge molecular biology and practical agronomy.

For farmers themselves, the adaptation is less about learning new application techniques - spraying is spraying - and more about integrating molecular tools into pest management strategies. This means understanding when RNA interference makes sense versus conventional options, how to monitor for resistance development, and how to combine RNA with other biological and cultural controls for robust, sustainable systems.

Investment in infrastructure will matter. While RNA sprays use existing application equipment, production facilities require fermentation capacity, purification systems, and formulation capabilities. Regions that build this infrastructure early will capture manufacturing jobs and become hubs for RNA pesticide production. Those that don't will depend on imports, transferring economic benefits elsewhere.

The research pipeline needs sustained investment to realize RNA technology's full potential. Current products represent perhaps 5% of possible applications. Funding for exploration of new pest targets, optimization of delivery systems, understanding of resistance mechanisms, and development of multi-target formulations will determine how quickly the field advances.

International cooperation will prove essential. Pests don't respect borders. Agricultural sustainability is a global challenge. Frameworks for sharing RNA sequences, coordinating resistance management, and ensuring access in developing nations need to develop alongside the technology itself. The pharmaceutical industry's struggles with vaccine equity provide relevant lessons about the consequences of failing to address global access early.

At the broadest level, RNA crop protection forces us to confront fundamental questions about how humanity should interact with living systems.

For the past 75 years, our approach to agricultural pests has been essentially chemical warfare - broad-spectrum toxins that kill indiscriminately, requiring constant escalation as targets develop resistance. This worked in the narrow sense of protecting yields, but created cascading consequences we're still discovering.

Genetic modification offered more precision but came with its own complications: permanent alterations, intellectual property battles, public distrust, and the nagging concern that we were changing ecosystems in ways we didn't fully understand.

RNA interference suggests a third path: precise, temporary, targeted intervention in biological systems without permanent modification. It's not manipulation through chemistry or alteration through genetics - it's communication through molecular messages that cells already understand.

RNA interference represents a fundamentally new relationship with nature - not dominating through force, not modifying permanently, but influencing temporarily through precise intervention that works with biological systems rather than against them.

This has implications far beyond agriculture. The same principles could apply to disease-carrying mosquitoes, invasive species, forest pests, aquaculture parasites - anywhere precise biological control matters. We're developing the capability to talk to living systems at the molecular level, telling specific organisms to stop producing specific proteins temporarily, without affecting anything else.

The philosophical implications are subtle but profound. This technology embodies a different relationship with nature - not dominating through force, not modifying permanently, but influencing temporarily through precise intervention. It suggests that sophisticated understanding can replace brute force, that we can work with biological systems rather than against them.

Of course, precision also enables new forms of risk. A technology that can silence any gene in any organism could theoretically target beneficial species, not just pests. The same specificity that makes RNA safe could make it dangerous if misused. The fact that it's temporary and degrades naturally provides inherent safety margins that GMOs and chemicals lack, but the potential for dual use exists.

These concerns deserve serious attention, but they shouldn't obscure the fundamental shift in possibility that RNA technology represents. For the first time, we have the tools for precision intervention in ecological systems without persistence or broad spectrum effects. How we use those tools, how we govern them, and what values guide their application will define an important part of our relationship with the living world for generations to come.

Agricultural history is littered with silver bullets that tarnished. DDT, the miracle pesticide. Atrazine, the wonder herbicide. Neonicotinoids, the safe alternative. Each promised to solve pest problems permanently. Each created new problems that emerged only with time and scale.

RNA crop protection could follow the same pattern - early promise giving way to unintended consequences. Resistance development could accelerate. Off-target effects might emerge that laboratory studies missed. Production costs might not decline as projected. Public acceptance could collapse if anything goes wrong.

But it might be genuinely different. The molecular basis for specificity is sound. The degradation pathways are well understood. The regulatory frameworks are more sophisticated than for previous agricultural technologies. The scientific community is more cautious, the public more engaged, and the need for sustainable alternatives more urgent.

What seems likely is that RNA technology will find its place in a diversified agricultural toolkit rather than displacing everything that came before. It will work best for pests where specificity matters most - where you need to target one species while protecting dozens of beneficial organisms in the same field. It will be most cost-effective for high-value crops where the economics justify the current price premiums. It will be most readily adopted in regions where chemical pesticide regulations are tightening but farmers still need effective control.

In 20 years, we'll probably look back on the mid-2020s as the inflection point when RNA crop protection transitioned from promising research to practical tool. The first EPA approvals happened. Production platforms matured. Costs began their decline. Farmers started testing it in commercial fields. The pathway from laboratory to landscape became clear.

Whether that pathway leads to transformation or disappointment depends on decisions being made now - by researchers choosing which problems to tackle, by investors determining which platforms to fund, by regulators balancing innovation and caution, by farmers deciding whether to try something new.

The technology itself is sound. The question is whether human systems - economic, regulatory, social - can adapt quickly enough to realize its potential before the problems it could solve get worse.

That's not just an agricultural question. It's a test of whether we can develop and deploy sophisticated biological technologies wisely, learning from past mistakes without being paralyzed by them. How we handle RNA crop protection will influence how we approach every molecular technology that follows.

The plants are already whispering to the pests. The question is whether we're ready to hear what they're saying - and act on it.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

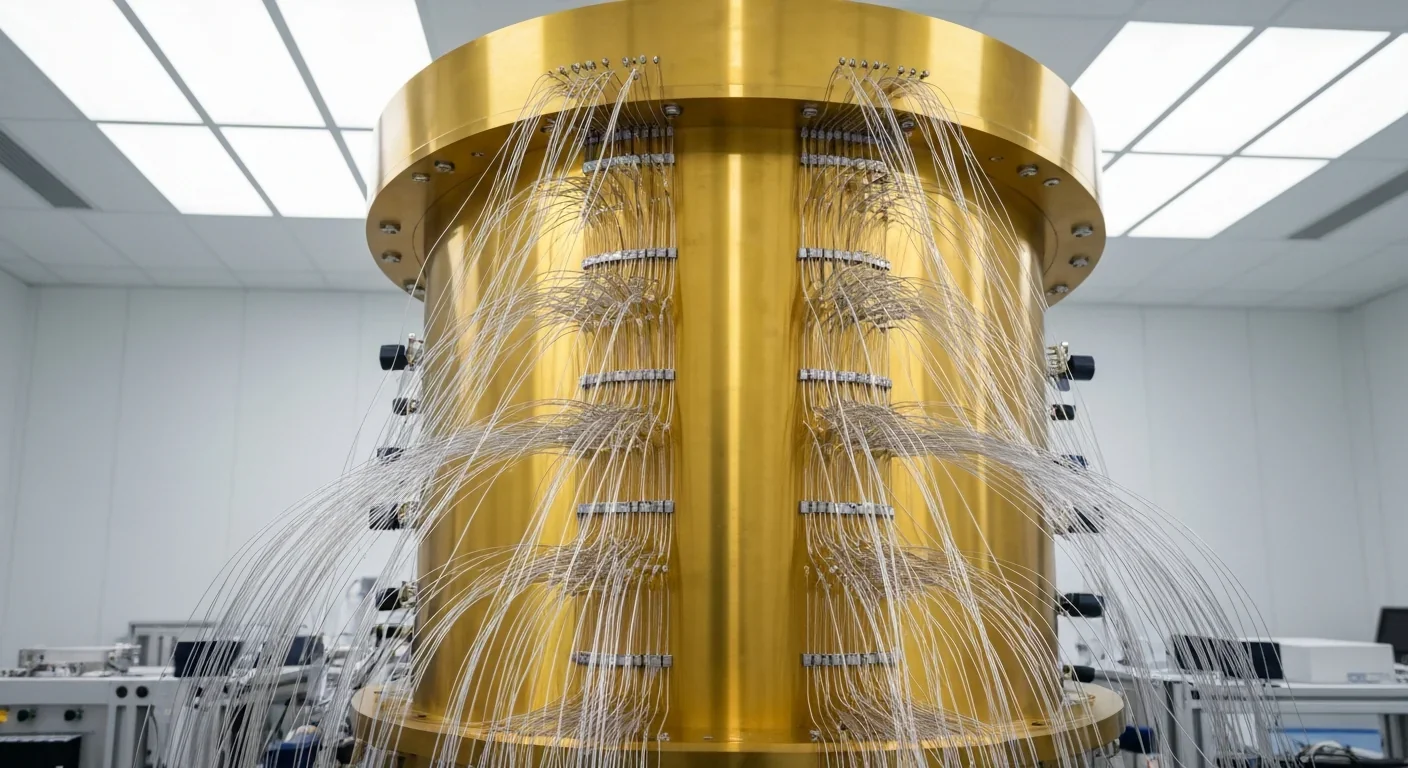

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.