AI Cameras Save Sea Turtles in Fishing Nets

TL;DR: Seaweed-based bioplastics are rapidly emerging as a viable alternative to petroleum packaging, with the market projected to triple to $3.62 billion by 2033. While currently 2-5x more expensive than traditional plastics, innovations in cultivation and processing are closing the cost gap, supported by strong policy momentum from EU regulations and carbon sequestration benefits that could unlock blue carbon credit revenue streams.

By 2030, the packaging you toss away after lunch might have started its life in an ocean farm, dissolving harmlessly back into the sea within hours. That's not sci-fi optimism - it's the trajectory of seaweed-based bioplastics, a technology that's already replacing petroleum packaging in fast-food chains and beverage brands across three continents. With the global seaweed bioplastic market projected to triple from $1.27 billion in 2024 to $3.62 billion by 2033, we're watching the early stages of a material revolution that could reshape the $500 billion packaging industry.

Every year, humanity produces over 400 million tons of plastic, and roughly half becomes packaging that's used once and discarded. The ocean now contains an estimated 25 trillion pieces of plastic debris, with microplastics appearing in human blood, lungs, and placentas. This isn't just an environmental crisis - it's a materials crisis. Petroleum-based plastics don't biodegrade; they fragment into smaller pieces that persist for centuries.

The conventional bioplastics that emerged as alternatives haven't solved the problem. Polylactic acid (PLA) costs $2.40 to $3.00 per kilogram - roughly double the price of traditional polyethylene - and still requires industrial composting facilities that most communities lack. Meanwhile, the truly biodegradable options, like polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA), can cost up to $9 per kilogram, pricing them out of mass-market applications.

Enter seaweed. Brown algae like kelp grow 30 to 60 times faster than land-based crops, require zero freshwater or arable land, and naturally contain alginate - a polymer that can be extracted and processed into packaging films, rigid containers, and coatings. Some species grow several centimeters per day, making them the fastest-growing biomass source on the planet.

The transformation from ocean plant to packaging material hinges on extracting and modifying natural polymers. Brown seaweeds - particularly kelp, rockweed, and Sargassum - contain up to 60% alginate in their cell walls. This polysaccharide acts as the structural backbone for seaweed bioplastics.

The production process begins with harvesting mature seaweed from ocean farms, typically after 4-6 months of growth. The algae are washed to remove salt and impurities, then processed to extract sodium alginate. This polymer can be chemically modified and combined with plasticizers - often FDA-approved compounds like choline chloride - to control flexibility, transparency, and barrier properties.

Researchers at Flinders University and the German biotech company One•Five developed a coating that replaces conventional plastic liners in fast-food packaging using this sodium alginate base. The material can be engineered to remain rigid and glass-like or stretch up to 130% of its original length, forming transparent films just 0.07 millimeters thick.

What makes seaweed bioplastics genuinely revolutionary isn't just what they're made from - it's how they break down. When these materials hit salt water, they can decompose within hours without forming microplastics.

What makes seaweed bioplastics genuinely revolutionary isn't just what they're made from - it's how they break down. Recent innovations use salt-bridge crosslinking, a chemistry trick where ionic bonds hold the polymer chains together in freshwater but dissolve rapidly in seawater. When these materials hit salt water, they can decompose within hours without forming microplastics, a stark contrast to petroleum plastics that persist for centuries.

The mechanical properties match or exceed traditional packaging in many applications. Alginate-based plastics scored a 5 out of 5 for marketability because of their almost identical texture and strength compared to petroleum plastics. They offer excellent film-forming capabilities suitable for flexible films, trays, and rigid containers.

The seaweed packaging industry has moved well beyond proof-of-concept. Notpla, a UK-based company, commands a 20-25% market share and leads the industry in Europe and North America. Their seaweed-based sachets and coatings have been deployed at major sporting events, replacing hundreds of thousands of single-use plastic cups.

In Indonesia, Evoware produces edible seaweed packaging that dissolves in hot water, targeting instant noodle wrappers and single-serve coffee pods. The company sources kelp from local ocean farmers, creating a supply chain that benefits coastal communities while displacing plastic.

Spain's B'ZEOS focuses on rigid seaweed containers for cosmetics and personal care products, demonstrating that the technology isn't confined to food packaging. Their containers maintain structural integrity for months on shelves but break down rapidly once discarded in compost or marine environments.

Sway Innovation Co. in California has partnered with major consumer goods brands to develop seaweed-based film for flexible packaging applications - the pouches and wrappers that account for the largest volume of single-use plastic waste. Their material can run on existing packaging machinery, removing one of the key adoption barriers.

The market momentum is real. Film products are growing at a 6.8% annual rate through 2035, outpacing the overall seaweed packaging market's 6% growth. Food and beverage packaging remains the dominant application, accounting for the largest market share in 2024.

Seaweed bioplastics offer more than just a disposal advantage - they flip the carbon equation. CO₂ emissions are reduced by 40% to 99% compared with conventional plastics, depending on the production process and feedstock.

The environmental benefit starts before harvest. As seaweed grows, it performs photosynthesis just like land plants, absorbing dissolved CO₂ from seawater. But unlike terrestrial agriculture, ocean farming requires zero irrigation, fertilizer, or land clearing. The farms themselves can sequester up to 140 tons of carbon per hectare annually in the sediments below them - storage rates comparable to mangroves and seagrass meadows.

"This could put seaweed farms in the running to issue blue carbon credits that are now commonly linked to these other ecosystems."

- Nature Climate Change, 2025

This has caught the attention of carbon credit markets. A 2025 Nature Climate Change study found that seaweed farm sediments store an average of 1.06 tons of CO₂ equivalent per hectare per year. Older farms in calm bays with fine sediments stored four times that amount, suggesting that strategic site selection could dramatically increase the carbon benefit.

Here's where it gets interesting: harvested seaweed incorporated into bioplastics locks that captured carbon away in durable goods, at least temporarily. Even after disposal, seaweed packaging that breaks down in compost or marine environments releases its carbon back into natural cycles, rather than adding new fossil carbon to the atmosphere.

The uncomfortable truth is that seaweed bioplastics currently cost 2 to 5 times more than traditional plastics. This price premium remains the single biggest barrier to mass adoption.

The cost structure breaks down into three main components: cultivation, processing, and distribution. Seaweed farming is labor-intensive, especially at small scales. Kelp lines must be seeded, monitored for pests and disease, and harvested by hand or with specialized vessels. Processing requires extracting and purifying alginate, then modifying it to achieve desired material properties. Each step adds expense.

But economies of scale are starting to kick in. Strategic partnerships between academia, industry, and government are enabling technological breakthroughs and supply-chain optimization. Automated seeding systems can reduce labor costs by up to 40%. New extraction techniques increase alginate yields from each ton of harvested seaweed.

The integration challenge is also being solved. Seaweed bioplastics are becoming more compatible with existing manufacturing equipment, reducing the capital investment needed for brands to make the switch. This matters enormously - if companies can use their current filling lines, thermoformers, and packaging machinery, adoption accelerates.

Market forecasts suggest the price gap will narrow significantly over the next decade. As production scales from thousands of tons annually to millions, per-unit costs drop. The seaweed packaging market is projected to grow from $770 million in 2025 to $1.37 billion by 2035, indicating sustained investment and capacity expansion.

The comparison to earlier green technologies is instructive. Solar panels cost $76 per watt in 1977; by 2020, that figure had fallen to $0.30 per watt - a 99% reduction driven by scale and innovation.

The comparison to earlier green technologies is instructive. Solar panels cost $76 per watt in 1977; by 2020, that figure had fallen to $0.30 per watt. Wind turbine costs dropped by 70% between 2009 and 2020. These learning curves happened because policy support created initial demand, which justified capital investment, which drove down costs through scale and innovation. Seaweed bioplastics are following a similar trajectory.

Government policy is the accelerant transforming seaweed bioplastics from niche curiosity to mainstream material. The EU Single-Use Plastics Directive, implemented in 2021, bans plastic cutlery, plates, straws, and expanded polystyrene containers across member states. Similar restrictions are proliferating: over 170 countries have enacted some form of plastic bag ban or tax.

These regulations create what economists call regulatory pull - they don't just discourage plastic use, they actively create demand for alternatives that meet specific sustainability criteria. The EU's comprehensive approach includes tax exemptions and R&D subsidies for biodegradable materials, making it the most conducive regulatory environment for bioplastic adoption.

The policy landscape isn't uniform. The United States has a patchwork of state and municipal regulations, with California, New York, and Washington leading on plastic restrictions. China has implemented national bans on plastic bags and utensils in major cities, though enforcement remains uneven.

Japan and South Korea are taking a different approach, focusing on circular economy initiatives that incentivize recyclability and compostability. These frameworks favor materials like seaweed bioplastics that offer verified end-of-life benefits.

One emerging policy tool deserves attention: blue carbon credits for seaweed farms. If seaweed cultivation is recognized as a carbon sequestration activity eligible for carbon offset markets, it could provide a secondary revenue stream that improves the economics of feedstock production. This would effectively subsidize the raw material cost for bioplastics production.

The regulatory momentum matters because it addresses the chicken-and-egg problem that plagues all emerging technologies. Brands hesitate to invest in new packaging materials without regulatory certainty. Investors hesitate to fund production scale-up without demonstrated market demand. Clear, durable policies break this deadlock.

Despite progress, significant technical challenges remain. The first is variability in feedstock quality. Seaweed composition changes with season, water temperature, nutrient availability, and harvest timing. This natural variation affects alginate content and molecular weight, which in turn impacts the properties of the final material.

Standardization of raw materials is critical for industrial production. Companies need consistent inputs to maintain product quality and meet regulatory specifications. Solutions include controlled aquaculture systems that regulate growing conditions, selective breeding programs to develop high-alginate cultivars, and post-harvest processing techniques that normalize composition.

Barrier properties remain a challenge for certain applications. Petroleum plastics excel at blocking oxygen, moisture, and light - critical for extending shelf life of perishable foods. Seaweed bioplastics can match these properties in some formulations but often require thicker films or composite structures that increase material costs.

The end-of-life infrastructure is inadequate. While seaweed packaging can biodegrade in marine environments or industrial compost facilities, most communities lack accessible composting infrastructure. Without proper disposal pathways, the biodegradability advantage is theoretical. Consumers may discard seaweed packaging in regular trash, where it ends up in landfills alongside conventional plastic.

"We aim to adapt this technology to current industry production lines."

- Zhongfan Jia, Lead Researcher, Flinders University

Labeling clarity is another friction point. Consumers struggle to distinguish between "biodegradable," "compostable," "marine-degradable," and "recyclable." Confusing claims undermine trust and reduce proper disposal. The industry needs standardized certification schemes and clear communication about disposal requirements.

Processing energy remains a concern. While seaweed cultivation has minimal environmental impact, extracting and modifying alginate requires energy and chemical inputs. Life cycle assessments must account for these processing impacts to verify that total environmental benefit remains positive compared to petroleum plastics.

Asia Pacific accounts for over 48% of the global seaweed bioplastic market, with China, Indonesia, South Korea, and Japan leading production. This dominance isn't accidental - it reflects centuries of seaweed cultivation expertise and established supply chains.

Indonesia alone produces over 10 million tons of seaweed annually, primarily Eucheuma species grown for carrageenan used in food products. This existing infrastructure provides a ready foundation for bioplastic production. Farmers already know how to cultivate seaweed at scale; the challenge is redirecting some of that production toward polymer extraction and creating processing facilities close to farming areas.

Japan's seaweed farming tradition extends back over 300 years, initially for food products like nori and kombu. Japanese companies are now leveraging that expertise to develop advanced bioplastic formulations. The country's emphasis on precision manufacturing and quality control is helping solve the feedstock consistency problem.

South Korea is investing heavily in ocean farming technology, including automated harvesting systems and real-time monitoring of water quality. These innovations could dramatically reduce production costs while improving yield and quality.

China's role is more complex. The country is simultaneously the world's largest producer of plastic waste and a growing leader in bioplastic production. Government policies are driving demand for alternatives while substantial capital is flowing into seaweed cultivation and processing capacity.

For Western markets to achieve competitive production, they'll need to either develop their own ocean farming capacity or establish reliable import relationships with Asian producers. The United States has suitable coastline in Alaska, Maine, and California, but current seaweed farming operations remain small-scale. Europe faces similar challenges, though Norway, Ireland, and Scotland have active aquaculture industries that could expand into energy and material production.

The geopolitics of seaweed supply chains will shape the industry's evolution. Just as rare earth elements and semiconductor production became strategic concerns, control over seaweed cultivation capacity could emerge as an economic advantage.

Ocean farming offers a rare opportunity: an industry that creates jobs while restoring ecosystems. Unlike extractive fishing, which depletes wild stocks, seaweed farming adds biomass to the ocean. The kelp forests that grow on farm lines provide habitat for fish, filter excess nutrients from coastal waters, and absorb CO₂ that would otherwise contribute to ocean acidification.

For coastal communities from Indonesia to Maine, seaweed cultivation represents economic diversification. Small-scale fishers can add seaweed lines to their operations, creating a secondary income stream that doesn't require expensive boats or equipment. In regions where overfishing has decimated traditional livelihoods, kelp farming offers an alternative that works with natural systems rather than against them.

The labor profile differs from industrial agriculture. Seaweed farming is physically demanding but doesn't require vast landholdings or expensive machinery, making it accessible to communities with limited capital.

The labor profile differs from industrial agriculture. Seaweed farming is physically demanding but doesn't require vast landholdings or expensive machinery. This makes it accessible to communities with limited capital but strong knowledge of local marine conditions. Women play a significant role in seaweed cultivation in many Asian countries, and the income from farming often goes directly to household expenses like education and healthcare.

There are legitimate concerns about industrialization. As seaweed farming scales up to meet bioplastic demand, will small-scale farmers benefit or get pushed aside by large corporations? The history of agricultural commodification suggests caution. Policy frameworks that protect small-holder rights, ensure fair prices, and prevent ecosystem damage from intensive monoculture will determine whether this industry lifts coastal communities or exploits them.

Marine spatial planning is critical. Seaweed farms require large ocean areas, which can conflict with fishing grounds, shipping lanes, and marine protected areas. Coordinated planning that balances competing uses while prioritizing ecosystem health will be essential as the industry expands.

The seaweed bioplastics industry stands at a familiar juncture. The technology works. The environmental benefits are substantial. The market opportunity is enormous. But the economics still favor conventional plastics, and the infrastructure to support widespread adoption doesn't yet exist.

History suggests what needs to happen next. First, continued policy pressure that makes petroleum plastic more expensive through taxes, bans, and extended producer responsibility schemes. These measures level the playing field and create stable demand signals.

Second, sustained R&D investment in cultivation efficiency, polymer extraction, and material science. The breakthroughs that will make seaweed bioplastics cost-competitive are achievable with focused research. Governments and private capital both have roles to play.

Third, infrastructure development for industrial composting and marine-degradable material processing. The promise of biodegradability only delivers if disposal systems actually exist. This requires coordination between municipalities, waste management companies, and material producers.

Fourth, public education about proper disposal and the genuine environmental benefits of seaweed packaging. Consumer skepticism about "greenwashing" is justified, but it shouldn't prevent adoption of legitimately superior materials.

The timeline for transformation could be surprisingly short. The global packaging industry turns over equipment and supply contracts every 5-10 years. If seaweed bioplastics reach cost parity by 2030 - a plausible scenario if current growth continues - they could capture 10-20% of the packaging market by 2035. That would represent 40-80 million tons annually, a genuine revolution in materials.

The question isn't whether seaweed bioplastics will replace petroleum packaging in some applications. The question is how fast, how comprehensively, and whether the benefits flow to communities and ecosystems or get captured by the same systems that created the plastic crisis in the first place.

This matters because materials shape civilization. The Bronze Age, the Iron Age, the Plastic Age - each named for the materials that defined human capability. If we're entering a Biological Materials Age, where polymers are grown rather than extracted, the implications extend far beyond packaging. Textiles, construction materials, and consumer goods could all shift to renewable feedstocks that integrate with natural cycles.

Seaweed is just the beginning. But it might be the beginning that matters most - the proof that industrial materials can come from living systems without destroying the planet. That's a revolution worth accelerating.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

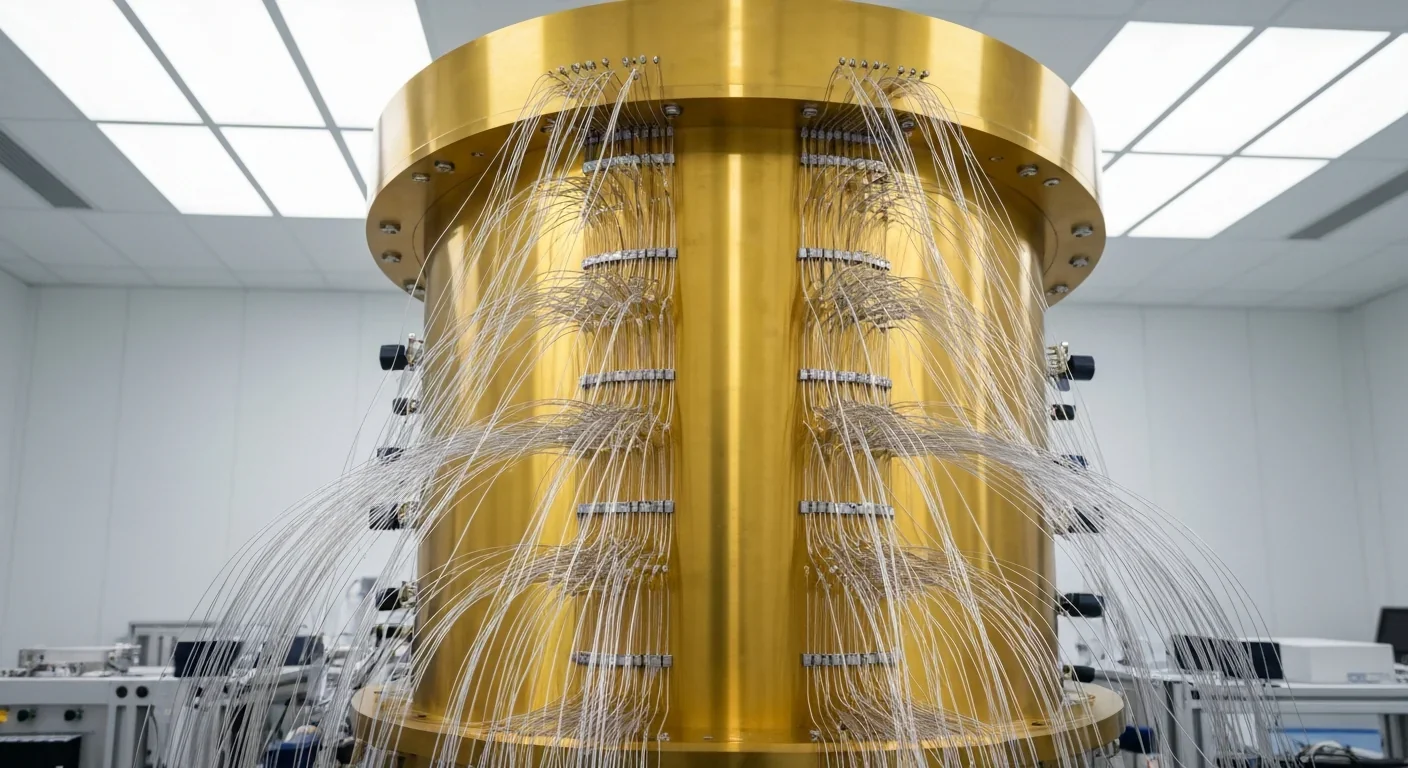

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.