AI Cameras Save Sea Turtles in Fishing Nets

TL;DR: Scientists are deploying thousands of underwater microphones to monitor ocean health through sound, tracking everything from whale migrations to coral reef vitality. This revolutionary acoustic monitoring technology provides continuous ecosystem health data while getting cheaper and smarter, though its real impact depends on whether society acts on what we're hearing.

The ocean doesn't just look different when it's in trouble. It sounds different too. Right now, thousands of underwater microphones scattered across the world's oceans are recording something remarkable: a planetary-scale symphony that reveals which ecosystems are thriving and which are gasping for breath. What scientists are hearing ranges from haunting whale songs to the crackling chorus of healthy coral reefs, but also unsettling silences where life once flourished.

This isn't just cool science - it's a diagnostic revolution. While satellites show us the ocean's surface and research vessels offer snapshots of specific locations, acoustic monitoring provides something unprecedented: continuous, 24/7 health checks of marine ecosystems we can't even see. And the technology that makes it possible is getting cheaper, smarter, and more powerful every year.

Acoustic monitoring works on a beautifully simple principle: everything in the ocean makes noise, and those noises tell a story. Marine mammals click and call to navigate and communicate. Fish grunt, croak, and drum during feeding and spawning. Healthy coral reefs produce a constant crackling soundscape as shrimp snap their claws and fish scrape algae. Even the physical environment contributes - waves breaking, ice cracking, sediment shifting.

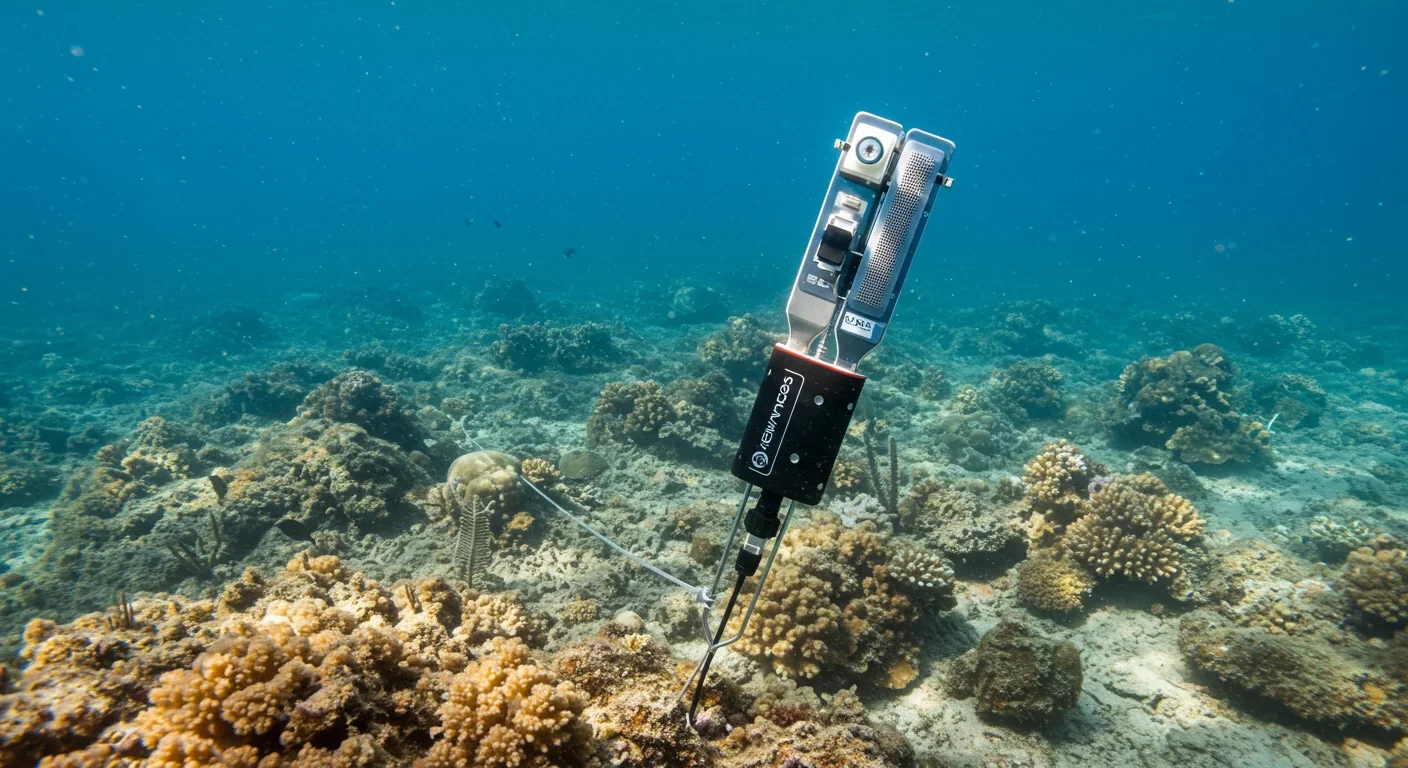

Scientists deploy hydrophones - underwater microphones - that can record these sounds for months or even years without human intervention. The data they collect isn't just audio; it's a biological census, behavioral study, and ecosystem health assessment all rolled into one.

Everything in the ocean makes noise, and those noises tell a story - from whale songs to snapping shrimp, the underwater soundscape is a real-time health monitor for marine ecosystems.

The technology itself has evolved dramatically. Early hydrophones were expensive, bulky affairs that required ships and specialized equipment. Today, researchers are using modified terrestrial recorders converted into waterproof hydrophones for a fraction of the cost. Some devices, like the open-source Hydromoth, cost just a few hundred dollars and can capture high-quality recordings that rival equipment costing tens of thousands.

This democratization matters because ocean acoustic monitoring faces a fundamental challenge: the ocean is really, really big. You can't understand planetary-scale changes with a handful of expensive sensors. But with affordable technology, researchers can deploy hundreds of recording stations across diverse habitats, creating acoustic observation networks that capture patterns no single study could reveal.

The killer application for acoustic monitoring is tracking marine species that are nearly impossible to study any other way. Take deep-diving whales. Traditional visual surveys can only count animals at the surface, and even then, only during daylight in decent weather. But acoustic sensors record every echolocation click and vocalization, creating detailed records of when whales are present, how many there are, and what they're doing.

Bottlenose dolphins, for instance, produce distinctive biosonar clicks at varying rates depending on their activity and environment. Recent research tracking dolphins over the West Florida Shelf found that click rates changed based on water depth, time of day, and proximity to important habitat features. These patterns help scientists identify critical feeding areas and migration corridors that need protection.

Fish populations present an even trickier monitoring challenge, but acoustic technology is cracking that too. Many fish species produce sounds during spawning - grunts, drums, croaks that create distinctive acoustic signatures. By identifying and counting these sounds, researchers can estimate population sizes and track spawning seasons without dropping a single net.

One particularly clever approach uses aquariums as acoustic research labs. Scientists record the specific sound signatures of different fish species in controlled settings, then use that acoustic library to identify the same species in wild ocean recordings. It's like building a sonic field guide for underwater life.

Coral reefs add another dimension entirely. Healthy reefs generate a complex soundscape dominated by snapping shrimp, along with sounds from fish, urchins, and other creatures. Degraded reefs go quiet. This acoustic difference is so pronounced that researchers can assess reef health just by listening - and they're training AI models to do it automatically.

"By characterizing the sounds produced by species in aquariums, future studies can utilize these data to identify species in natural habitats."

- Marine Bioacoustics Research

Recording ocean sounds is one challenge. Making sense of years of continuous audio data is another beast entirely. A single hydrophone recording for a year generates roughly 2,100 hours of audio - that's nearly 90 days of non-stop listening. Multiply that by dozens or hundreds of sensors, and human analysis becomes impossible.

Enter artificial intelligence. Machine learning models can scan months of recordings in hours, automatically detecting and classifying thousands of different sound types. Modern AI systems don't just identify species; they can distinguish between foraging, socializing, and distress calls, track individual animals across recordings, and even flag unusual patterns that might indicate ecosystem changes.

One breakthrough came from pretrained neural networks that learned to understand soundscapes without needing extensive labeled training data. These models can analyze coral reef sounds and predict ecosystem health with remarkable accuracy. Others use multi-task learning approaches to simultaneously identify species, classify behaviors, and filter out background noise - all from the same audio stream.

Hardware advances are keeping pace too. Autonomous recording units can now operate for years on battery power, some with solar recharging capabilities. Newer systems integrate multiple sensors, combining acoustic data with measurements of temperature, salinity, and current speed to build richer pictures of ocean conditions.

Some researchers are even deploying acoustic sensors on underwater gliders and autonomous vehicles, creating mobile monitoring stations that can cover vast areas while recording continuously. These platforms are turning acoustic monitoring from a stationary observation post into an active exploration tool.

The promise of acoustic monitoring isn't theoretical - it's already delivering conservation victories and scientific discoveries that would have been impossible otherwise.

In protected marine areas, acoustic sensors have become enforcement tools. Illegal fishing vessels create distinctive engine signatures and sonar pings that monitoring systems can detect from miles away. Some protected areas now use automated alert systems that notify enforcement officers when suspicious vessel sounds are detected, dramatically improving their ability to catch poachers in the act.

Climate change impacts are showing up in soundscapes too. Research comparing historical and recent recordings from the same locations reveals that ocean soundscapes are changing as waters warm. In some shallow habitats, the dominant biological sound producers are shifting their acoustic output in response to temperature changes - essentially, the ocean is getting louder as it warms.

This matters because these soundscape shifts may indicate broader ecosystem reorganization. Species that rely on sound for navigation, communication, or locating suitable habitat could be affected by these changes. Acoustic monitoring gives us an early warning system for these disruptions.

As oceans warm, their soundscapes are changing - the acoustic signatures of entire ecosystems are shifting in response to climate change, providing an early warning system for ecological disruption.

Marine mammal conservation has been particularly transformed. Before widespread acoustic monitoring, researchers struggled to track population trends for many whale and dolphin species. Now, acoustic data provides year-round presence information that's revealing migration patterns, breeding areas, and seasonal movements we never knew existed.

Here's the uncomfortable truth that acoustic monitoring has made impossible to ignore: we've made the ocean incredibly noisy, and that noise is harming marine life in ways we're only beginning to understand.

Commercial shipping, oil and gas exploration, military sonar, pile driving for offshore construction - all of these activities pump intense sound into the marine environment. For animals that rely on sound to navigate, find food, attract mates, and avoid predators, this anthropogenic noise is like trying to have a conversation in a nightclub cranked to eleven.

Chronic exposure to vessel noise can interfere with whale communication over distances of hundreds of miles. Dolphins in busy shipping lanes show altered behavior patterns and increased stress hormones. Even fish populations can be affected - some species avoid noisy areas entirely, fragmenting their habitat in ways that reduce breeding success and feeding efficiency.

The ocean noise pollution problem also creates a technical challenge for researchers: distinguishing biological sounds from human-generated noise. A ship passing overhead can mask whale calls. Seismic surveys can drown out fish vocalizations. Heavy storms create their own acoustic chaos. Modern acoustic monitoring systems have to account for all of this, filtering signal from noise to extract meaningful biological data.

But this challenge cuts both ways. The same acoustic monitoring networks that track marine life are also documenting the scale and impact of ocean noise, providing the evidence needed to push for quieter ship designs, restrictions on seismic surveys in sensitive areas, and noise limits in marine protected areas. Some port authorities are now using acoustic monitoring to identify the loudest vessels and incentivize shipping companies to reduce underwater noise emissions.

Scientific data only matters if it changes decisions. Acoustic monitoring is starting to reshape marine conservation policy in tangible ways.

The most direct impact comes through marine spatial planning - the process of deciding which ocean areas to protect, where to allow development, and how to manage human activities. Acoustic data revealing critical habitat for endangered species has influenced decisions to reroute shipping lanes, restrict certain fishing practices, and establish new marine protected areas.

Speed restrictions for vessels in areas with high whale presence are increasingly supported by acoustic monitoring data showing when and where marine mammals are most abundant. These restrictions reduce both ship strike risk and noise pollution, but they're only politically feasible when backed by solid evidence of species presence - evidence that acoustic monitoring provides year-round.

"Acoustic monitoring provides continuous, year-round evidence of species presence that makes conservation restrictions both scientifically justified and politically feasible."

- Marine Conservation Policy Research

Fisheries management is another arena where acoustic data is proving valuable. For species that produce spawning sounds, acoustic monitoring can identify spawning periods and locations with precision that traditional methods can't match. This information helps managers set seasonal closures that actually protect fish during vulnerable periods, rather than relying on historical patterns that may no longer hold as ocean conditions change.

International efforts to monitor ocean health are increasingly incorporating acoustic observations. The Global Ocean Observing System, which coordinates ocean measurements from dozens of countries, now includes acoustic monitoring as a recognized observation method. This legitimizes the approach and encourages broader deployment of hydrophone networks.

Success brings its own problems. As acoustic monitoring expands, researchers are drowning in more data than they can analyze. A network of just 50 hydrophones recording continuously for a year generates roughly 438,000 hours of audio - about 50 years of continuous listening if you tried to review it all in real-time.

This creates bottlenecks that slow scientific progress. Researchers spend months analyzing data from studies that took weeks to conduct. Important patterns might be invisible simply because no one has had time to look at the right segment of recordings yet.

The solution involves both better tools and different approaches. AI-powered analysis systems are getting faster and more accurate, but they still require training, validation, and human oversight. Some research teams are developing visualization tools that let scientists scan months of acoustic data at a glance, spotting unusual patterns that merit closer examination.

Cloud computing and collaborative data sharing are also part of the picture. Rather than each research team analyzing their own datasets in isolation, some are creating shared acoustic databases and analysis pipelines that let researchers compare patterns across regions and time periods. This kind of synthesis is where acoustic monitoring really shines - revealing ocean-scale trends that individual studies would never detect.

Standardization remains a challenge though. Different research groups use different recording equipment, sampling rates, and analysis methods. This makes it difficult to compare results across studies or combine datasets. The field is gradually converging on common standards and protocols, but progress is slower than the rate of data accumulation.

Acoustic monitoring isn't replacing other ocean observation methods - it's complementing them in ways that make the whole system more powerful.

Satellite remote sensing excels at measuring surface conditions: temperature, chlorophyll concentration, wave height. But satellites can't see underwater life or detect what's happening in the deep ocean. Acoustic sensors fill that gap, providing biological and behavioral data that remote sensing misses.

Traditional ship-based surveys offer detailed snapshots of specific locations and times. Acoustic monitoring adds the temporal dimension - continuous observations that capture daily, seasonal, and annual cycles. When researchers combine visual surveys with acoustic data from the same locations, they get much richer pictures of ecosystem dynamics.

Environmental DNA (eDNA) sampling - collecting water samples and sequencing genetic material to identify species - is another complementary technique. eDNA tells you what species are present, but not their abundance, behavior, or health. Acoustic data adds those dimensions, revealing not just which animals are around but what they're doing and how they're responding to environmental conditions.

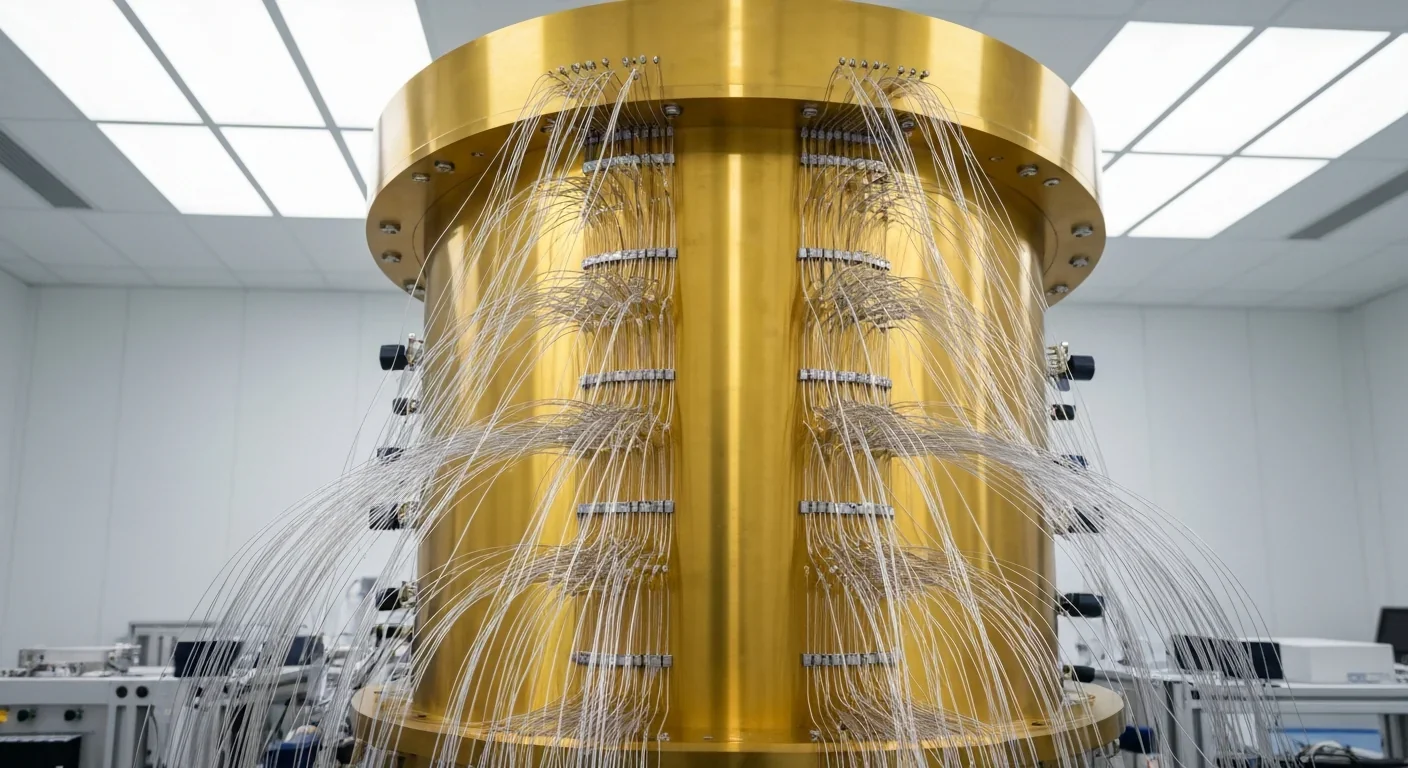

Some cutting-edge ocean observatories are integrating all of these approaches. Multi-sensor platforms combine acoustic monitors with cameras, environmental sensors, and eDNA samplers, creating comprehensive monitoring stations that capture nearly everything happening in their vicinity. These systems are expensive, but they generate the kind of rich, multi-dimensional data that's needed to truly understand complex ecosystems.

The next decade will likely see acoustic monitoring expand from specialized research tool to routine component of ocean management. Several developments are accelerating this transition.

Cost continues to decline. What required a $50,000 investment five years ago can now be achieved with equipment costing a few thousand dollars. This makes acoustic monitoring accessible to smaller research institutions, conservation organizations, and even citizen science projects.

The cost of acoustic monitoring equipment has dropped by 90% in five years, making ocean listening technology accessible to conservation groups and citizen scientists worldwide.

Processing automation is improving rapidly. AI models that struggled to classify sounds just a few years ago now match or exceed human expert performance on many tasks. As these systems get better, the bottleneck shifts from analysis to deployment - we can process more data than we're currently collecting.

Real-time capability is emerging too. Rather than recovering hydrophones months after deployment and then analyzing recordings, newer systems can transmit data via satellite or acoustic modems, enabling near-real-time monitoring. This opens possibilities for adaptive management - adjusting conservation measures in response to current conditions rather than historical patterns.

Commercial applications are also developing. Offshore wind developers are using acoustic monitoring to assess impacts on marine mammals and adjust construction schedules to minimize disturbance. Aquaculture operations employ acoustic sensors to monitor fish health and feeding behavior. Even maritime security has acoustic dimensions, with sensors detecting unauthorized vessels in protected areas or near critical infrastructure.

Perhaps the most profound shift acoustic monitoring enables is conceptual. For most of human history, we've thought about ocean ecosystems primarily through visual metaphors. We talk about what we can see, catch, or photograph.

But most marine life doesn't prioritize vision. Sound travels much farther and faster underwater than light. Many species are primarily acoustic animals - they navigate by sound, communicate through calls, find prey by listening. For them, the ocean is fundamentally an acoustic space.

By learning to listen, we're starting to understand the ocean more as its inhabitants experience it. We're discovering that soundscapes carry information about ecosystem health and resilience that visual surveys miss. We're finding that human-generated noise isn't just annoying background interference - it's habitat degradation as serious as pollution or overfishing.

This shift in perspective is already influencing conservation strategy. Protecting quiet areas is becoming recognized as important as protecting feeding grounds or breeding sites. Understanding acoustic habitat requirements is informing species recovery plans. The sounds of healthy ecosystems are becoming restoration targets - scientists want degraded areas to sound like healthy ones again.

There's something uniquely powerful about audio as scientific data. Charts and graphs communicate information, but sound evokes understanding in a different way. When you listen to a healthy coral reef's crackling chorus, then hear the eerie silence of a bleached reef, the ecological collapse isn't abstract - it's visceral.

This emotional dimension matters for ocean conservation in ways that are hard to quantify but impossible to dismiss. Photos of coral bleaching communicate damage effectively, but the audio of reef degradation hits differently. It creates a gut-level understanding of loss that can motivate action.

Scientists are increasingly making ocean soundscapes publicly available, letting anyone listen to what healthy ecosystems sound like and compare them to degraded areas. These acoustic portraits of ocean health are becoming powerful tools for education and advocacy.

The recordings also serve as baselines for the future. Just as historical photos let us see how landscapes have changed, acoustic archives will let future scientists hear how ocean soundscapes evolved during the critical decades of the 21st century. We're creating an audio record of ecosystem transformation that future generations will study to understand what we lost - and hopefully, what we saved.

The ocean's acoustic future could go two directions. In one scenario, monitoring networks expand globally, processing gets smarter, and we develop a real-time understanding of ocean health that guides rapid, effective conservation responses. Soundscapes stabilize or even recover as we reduce noise pollution, protect key habitats, and manage fisheries based on actual ecosystem dynamics rather than outdated models.

In another scenario, we collect ever more data that mostly documents continuing decline. Acoustic monitoring becomes an autopsy tool - precisely measuring what we're losing without the political will to stop losses. The recordings preserve sounds of species and ecosystems that quietly slip toward extinction.

Which future we get depends on whether acoustic monitoring remains primarily a scientific tool or becomes a decision-making infrastructure. The technology already exists to deploy monitoring networks at scales that would provide near-complete coverage of coastal waters and many offshore areas. What's missing isn't technical capability but sustained funding and political commitment.

Some progress indicators are encouraging. More marine protected areas include acoustic monitoring as part of their management plans. More governments recognize ocean noise as a pollutant requiring regulation. More offshore developers must conduct acoustic impact assessments before beginning operations.

But most ocean areas remain acoustically unmonitored. Most acoustic datasets are never fully analyzed. Most conservation decisions are still made with minimal acoustic information. The gap between what's possible and what's happening remains vast.

Here's what makes acoustic monitoring both exciting and unsettling: it works. The technology delivers on its promise. We can track species we could never census before, detect ecosystem changes in real-time, monitor vast areas continuously, and do it all more cheaply than traditional methods.

"We're rapidly losing the excuse of ignorance. When coral reefs fall silent, when whale populations shift, when fish spawning sounds disappear - we know it's happening. The hydrophones are recording it all."

- Marine Conservation Science

This means we're rapidly losing the excuse of ignorance. When coral reefs fall silent, when whale populations shift their distributions, when fish spawning sounds disappear from once-productive areas - we know it's happening. The hydrophones are recording it all.

The question isn't whether acoustic monitoring can help us understand and protect ocean ecosystems. It already does. The question is whether understanding translates to action fast enough to matter.

Every underwater microphone operating right now is taking the ocean's pulse, listening for the rhythms of life and the warning signs of decline. What we do with what we're hearing will determine whether future generations inherit oceans that still sing with life - or ones that have gone quiet.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.