AI Cameras Save Sea Turtles in Fishing Nets

TL;DR: Great whales are worth up to $2 million each in carbon credits through natural sequestration, creating a trillion-dollar conservation incentive that's reshaping marine policy and aligning economic interests with climate protection.

Great whales are swimming carbon vaults. Over their decades-long lifespans, baleen whales like blue whales and humpbacks accumulate roughly 33 tonnes of carbon in their massive bodies. When they die and sink to the ocean floor in what scientists call a whale fall, that carbon gets locked away in deep-sea sediments for centuries, sometimes millennia.

But the real climate magic happens while they're alive. Whales fertilize the ocean surface with their waste, creating massive blooms of phytoplankton that pull carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. These microscopic plants form the foundation of marine food webs and collectively absorb about 40% of all carbon dioxide produced globally. Without whales pumping nutrients from the deep ocean to sunlit surface waters, those phytoplankton populations would crash.

This phenomenon, called the whale pump, works because whales dive deep to feed but surface to breathe and defecate. Their iron-rich fecal plumes act like fertilizer, boosting phytoplankton growth. Research suggests that whale poop could have been responsible for fertilizing vast stretches of historical oceans, potentially capturing far more carbon than the whales themselves store in their bodies.

Marine biologists estimate that before industrial whaling, whale populations may have enhanced phytoplankton productivity enough to capture 1.5 million tonnes of CO₂ annually through whale falls alone. Add in the whale pump effect, and the total climate impact could be significantly larger.

Each great whale acts as a multi-million-dollar carbon sequestration system, working 24/7 for decades without human intervention or cost.

Here's where it gets economically interesting. If each great whale sequesters carbon worth avoiding climate damages, you can attach a dollar figure to that service. The International Monetary Fund did exactly that, producing the widely cited $2 million per whale valuation. They based this on carbon's social cost - the economic damage that each tonne of CO₂ causes through climate impacts like sea-level rise, extreme weather, and agricultural disruption.

The math works like this: a whale stores 33 tonnes of carbon in its body, equivalent to about 120 tonnes of CO₂. At a conservative social cost of carbon around $100 per tonne, that's $12,000 just for the whale's body carbon. But factor in the whale's lifetime contribution to phytoplankton productivity through the whale pump, and the numbers balloon. Over an 80-year lifespan, economists calculate a single whale could help sequester thousands of additional tonnes of CO₂ through enhanced ocean productivity.

Multiply that by global whale populations, and you're looking at ecosystem services worth hundreds of billions of dollars. The IMF suggested the total value of great whales could exceed $1 trillion if populations recovered to pre-whaling numbers.

That's a staggering figure, but it comes with asterisks. Carbon accounting for living animals involves massive uncertainty. How much phytoplankton growth can we actually attribute to whale activity versus ocean currents, upwelling zones, and other nutrient sources? How long does whale fall carbon really stay locked in sediments? Scientists debate these questions vigorously, with skeptics arguing the whale carbon hype far exceeds the measurable climate benefit.

Understanding whales' economic value requires confronting what we destroyed. Commercial whaling killed an estimated 3 million whales in the 20th century alone, reducing some populations by 99%. Blue whales, the largest animals ever to exist, dropped from perhaps 350,000 individuals to fewer than 3,000.

That wasn't just a biodiversity tragedy. It was a climate event. Each killed whale represented decades of carbon pumping that would never happen, phytoplankton blooms that wouldn't materialize, and tonnes of carbon that got processed into whale oil and bone meal instead of sinking to the seafloor. Historical analysis suggests that whaling effectively turned the ocean's carbon sequestration capacity down by removing the ecosystem engineers that maintained it.

Before whaling, whale biomass in the oceans may have exceeded 200 million tonnes. Today it's a fraction of that. The carbon cycle disruption from losing those animals rippled through marine ecosystems in ways we're still discovering. Recent research shows that whale population recovery could restore some of that lost carbon sink capacity, but we're talking about timescales of decades to centuries, not years.

The historical parallel isn't perfect, but imagine clear-cutting a rainforest the size of Argentina. That's roughly the scale of carbon cycling capacity we eliminated when we nearly drove great whales to extinction.

Whales aren't the only marine carbon sinks getting economic attention. The concept of blue carbon includes mangrove forests, salt marshes, and seagrass meadows, all of which bury carbon in coastal sediments at rates far exceeding terrestrial forests per unit area.

A hectare of seagrass can sequester carbon twice as fast as a hectare of temperate forest. Mangroves are even more efficient, storing up to four times more carbon per hectare than rainforests. These ecosystems have concrete boundaries you can measure and protect, making them attractive for carbon credit markets.

Whales, by contrast, migrate across ocean basins. A humpback whale might feed in Antarctic waters, breed near the tropics, and fertilize phytoplankton across thousands of kilometers. How do you create property rights or conservation credits for an animal that crosses a dozen national jurisdictions?

"If preserving forests generates carbon credits because trees sequester CO₂, why shouldn't preserving whales? Both provide ecosystem services that benefit the entire planet."

- Climate policy researchers

That complexity hasn't stopped entrepreneurs and conservationists from trying. Some proposals suggest international whale carbon credits that could be traded like other environmental commodities, with revenue funding whale watching tourism, anti-whaling patrols, and marine protected areas. The revenue potential could transform economics for coastal communities that currently have limited incentive to protect whale populations.

But unlike mangroves that stay put, whale carbon accounting faces unique challenges. Scientists can't easily measure an individual whale's contribution to phytoplankton productivity or guarantee how long whale fall carbon stays sequestered. Those uncertainties make verification and monitoring difficult, potentially undermining market credibility.

The economic framing of whale conservation is already influencing policy. Several Caribbean nations have proposed whale protection zones that could generate carbon credits, using the $2 million per whale valuation to justify international climate financing for marine conservation.

At international climate conferences, whale conservation has appeared in discussions about nature-based climate solutions. Countries with recovering whale populations argue they should receive climate mitigation credit for protecting these animals, similar to how rainforest nations can access funds for avoiding deforestation.

The logic is compelling: if preserving forests generates carbon credits because trees sequester CO₂, why shouldn't preserving whales? Both provide ecosystem services that benefit the entire planet, not just the countries where they're located. A whale swimming off Chile's coast fertilizes phytoplankton that absorbs carbon produced by factories in China.

This reasoning could unlock new conservation funding streams. Traditional marine protection relies on government budgets, philanthropic donations, and limited ecotourism revenue. Carbon markets could potentially generate billions in whale conservation funding by treating whale recovery as a climate mitigation strategy eligible for the same financial mechanisms that support renewable energy and forest protection.

But translating whale biology into tradable carbon credits faces political and technical hurdles. International carbon markets require rigorous monitoring and verification to prevent fraud and double-counting. With whales, you'd need to track population numbers, migration patterns, survival rates, and somehow estimate their contribution to ocean productivity across vast, jurisdiction-crossing territories.

Some critics worry that putting economic values on whales reduces them to carbon accounting entries, obscuring their intrinsic worth and ecosystem roles beyond climate. What happens when carbon market economics suggest protecting one species over another based purely on sequestration rates? Does a blue whale get more protection than a smaller, less carbon-dense species?

The fundamental shift: whales are transitioning from endangered species we protect morally to economic assets that provide measurable climate services worth billions.

Despite the uncertainty, the economics of whale conservation are already changing. Countries like Iceland and Norway, which maintained limited whaling programs, face increasing economic pressure as whale watching tourism far exceeds whaling revenue. Iceland's whale watching industry generates an estimated $15 million annually and is growing, while commercial whaling produces a fraction of that.

Adding carbon credit value could tip those economics further. If a living whale generates $2 million in climate benefits over its lifetime, plus tourism revenue, plus ecosystem services like fishery productivity through nutrient cycling, the economic case for killing whales collapses entirely. Even from a purely financial perspective, whales are worth more alive than dead.

Marine protected areas built around whale conservation are becoming economic engines. Some regions have created whale reserves, using both tourism and carbon sequestration arguments to justify the designation. Countries are exploring carbon credit markets to fund monitoring and enforcement.

Similar proposals are emerging in the Pacific, where island nations recognize that their whale populations represent potential climate financing opportunities. Rather than viewing whales as common-pool resources anyone can harvest, they're framing them as national assets providing global climate services deserving of international payment.

This shift mirrors how rainforest nations negotiated mechanisms that pay countries for preserving forests. The next decade could see similar frameworks for marine megafauna, with whale conservation funded through climate finance rather than traditional environmental budgets.

Here's what keeps scientists cautious: we don't actually know exactly how much carbon whales help sequester through the whale pump mechanism. The studies suggesting massive climate benefits rely on models with significant uncertainty ranges. When researchers dig into the numbers, the measurable impact is often smaller than headlines suggest.

For example, that 1.5 million tonnes of CO₂ sequestered annually through whale falls sounds impressive until you realize global CO₂ emissions exceed 35 billion tonnes yearly. Whales might contribute meaningfully to ocean carbon cycling, but they're not going to solve climate change. Protecting whales for their carbon value makes sense as part of a comprehensive climate strategy, not as a substitute for reducing fossil fuel emissions.

Recent research at Península Valdés in Argentina found that areas with high whale concentration showed elevated carbon and nitrogen stocks in sediments, suggesting measurable local impacts. But extrapolating those localized findings to global scales requires assumptions about whale behavior, migration, and ecosystem interactions that remain poorly understood.

Scientists are working to improve these estimates. New tracking technologies allow researchers to monitor whale movements in unprecedented detail. Satellite data helps measure phytoplankton blooms and correlate them with whale presence. Sediment analysis of whale fall sites provides direct evidence of carbon burial rates.

As the data improves, carbon accounting methods will become more robust. But current valuations remain educated guesses based on simplified models. The $2 million per whale figure should be understood as an order-of-magnitude estimate, not a precise market price.

Beyond carbon, whales serve as ecosystem engineers that structure marine environments in ways that cascade through food webs. When whale populations collapsed, ecosystems shifted. Prey species like krill and small fish changed distribution patterns. Predators adapted to different food sources. The recovery of whale populations is essentially rewinding those disruptions.

In Antarctica, whale feeding patterns help maintain krill populations that themselves play crucial roles in carbon cycling. Krill transport carbon from surface waters to depth through their daily vertical migrations. Supporting healthy krill populations supports that carbon pump mechanism.

Similarly, in coastal ecosystems, whales help redistribute nutrients in ways that benefit everything from seabirds to commercial fisheries. The economic value of those services likely exceeds the carbon sequestration value, but it's harder to quantify and commoditize.

This is where carbon market framing gets reductive. Whales provide multiple overlapping ecosystem services that interact in complex ways. Isolating carbon sequestration for market purposes might miss the broader picture or create perverse incentives that optimize for carbon at the expense of other ecosystem functions.

Most great whale populations are recovering, but slowly. Blue whales, nearly extinct by the 1960s, now number around 25,000 globally, still a fraction of historical populations. Humpback whales have bounced back more successfully, reaching perhaps 40% of pre-whaling abundance in some regions.

Full recovery could take another century, assuming we maintain protections and address new threats like ship strikes, fishing gear entanglement, and climate-driven changes to prey distribution. Each recovered whale represents additional carbon sequestration capacity, but the timeline for restoring whale-mediated ocean carbon cycling to pre-whaling levels stretches across generations.

Climate change itself complicates recovery. Warming waters shift prey species ranges, potentially separating whales from food sources they evolved to exploit. Ocean acidification affects the phytoplankton that form the base of whale food webs. The ocean whales are recovering into is fundamentally different from the one they were removed from.

But conservation success stories exist. The recovery of humpback whales in the North Pacific shows that with sufficient protection, populations can rebound within decades. Each recovered population represents not just a conservation win but also a restoration of ecosystem function, including carbon cycling services.

"We're moving toward economic systems that reward preservation rather than extraction, that value living ecosystems rather than just the commodities we can extract from them."

- Conservation economists

Maybe the most important insight isn't whether whales are worth $2 million each in carbon terms. It's that we're finally attempting to account for ecosystem services that economics traditionally ignored. For centuries, we treated whales as unlimited resources to harvest. Then we recognized them as endangered species deserving protection. Now we're quantifying their contributions to planetary systems in ways that make conservation economically rational, not just emotionally appealing.

Whether that valuation holds up to scientific scrutiny matters less than the shift it represents. We're moving toward economic systems that reward preservation rather than extraction, that value living ecosystems rather than just the commodities we can extract from them.

The whale carbon market might never reach $1 trillion. The per-whale valuation might get revised down as science improves. But the principle that nature provides valuable services that should factor into economic decisions is taking hold. Whales just happen to be a charismatic, measurable example of that broader rethinking.

If putting a price on whales helps us protect them, it's a pragmatic tool worth using. The real danger isn't valuing nature too highly. It's continuing to treat ecosystem services as free and infinite until we've depleted them beyond recovery. By the time we realize what we've lost, the cost of restoration dwarfs what preservation would have required.

Whales have been teaching us that lesson for 50 years. Maybe now, finally, we're listening.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

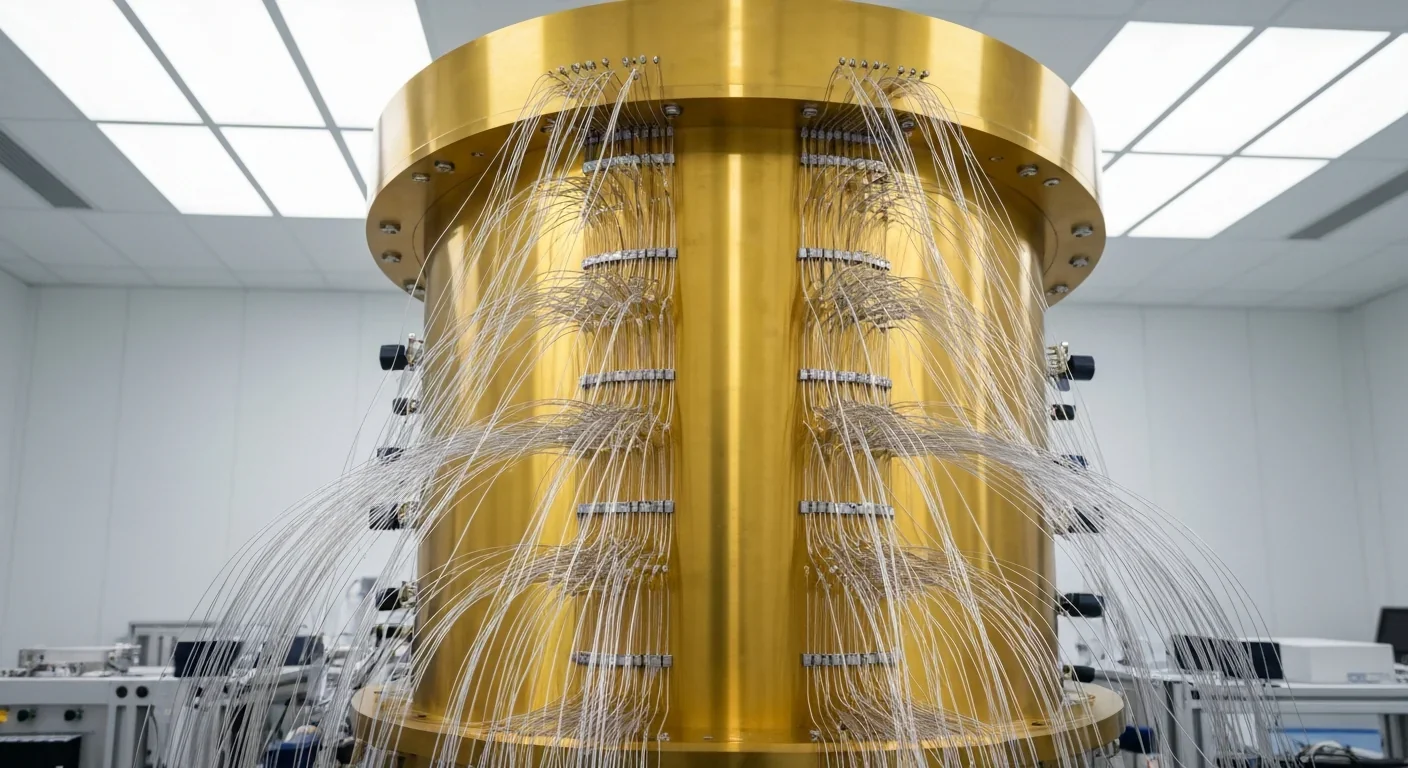

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.