AI Cameras Save Sea Turtles in Fishing Nets

TL;DR: Wildlife corridors are reconnecting fragmented ecosystems worldwide through innovative infrastructure like overpasses and continental-scale networks. From Yellowstone to Yukon's 2,100-mile corridor to Europe's Green Belt, these projects reduce collisions by up to 97%, boost animal movement by 50%, and enable climate adaptation.

By 2030, North America's most ambitious conservation project will have stitched together over 2,000 miles of wild country - from the sagebrush of Wyoming to the boreal forests of the Yukon. The Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative isn't just protecting land. It's rebuilding the connective tissue that habitat destruction has severed, creating highways for grizzly bears, wolves, and elk to roam as they did before roads, cities, and farms carved the continent into isolated islands.

This is the frontier of 21st-century conservation: not fortress parks locked behind boundaries, but living networks that pulse with migration. Wildlife corridors represent a fundamental shift in how we think about protecting nature - from preserving static patches to reconnecting entire ecosystems. And the results are remarkable. Studies show that corridors increase movement between habitat patches by approximately 50%, while innovative crossing structures reduce wildlife-vehicle collisions by up to 97%.

What began as an ecological theory is now reshaping landscapes worldwide, from Europe's Iron Curtain-turned-Green Belt to South America's first continental jaguar corridor. These aren't just conservation wins - they're massive infrastructure projects that challenge us to reimagine how human development and wild nature can coexist.

Picture a forest chopped into a hundred pieces by highways, subdivisions, and farmland. Each fragment might look green on a map, but for the animals living there, it's an ecological trap. Habitat fragmentation doesn't just shrink available territory - it isolates populations, preventing breeding, blocking seasonal migrations, and turning gene pools into stagnant ponds.

The math is brutal. When populations become isolated, genetic diversity plummets. Inbreeding increases. Local extinctions spike. A 2010 meta-analysis by Gilbert-Norton found that connectivity interventions boost animal movement by roughly 50%, but the flip side is stark: roads affect at least one-fifth of U.S. land area ecology, creating barriers that fragment what was once continuous habitat.

Climate change compounds the crisis. Species need to shift their ranges poleward or upslope as temperatures rise, but they can't teleport across hostile terrain. Without corridors, populations become stranded in unsuitable habitat, ecological refugees with nowhere to flee. Research indicates that climate corridors could be critical for species adaptation, allowing populations to track shifting temperature zones across landscapes.

That's where wildlife corridors come in - strips of habitat that connect fragmented patches, enabling animals to move, breed, and adapt. Think of them as ecological bridges, except instead of spanning rivers, they span the gaps humans created.

Wildlife corridors increase animal movement between habitat patches by approximately 50%, while reducing isolation-driven genetic decline that leads to local extinctions.

Building an effective wildlife corridor isn't as simple as leaving a strip of trees standing. Ecologists have spent decades figuring out what actually works. Width matters enormously. A corridor too narrow becomes a gauntlet for predators rather than a safe passage. Too wide, and land acquisition costs become prohibitive. The sweet spot varies by species - what works for insects won't work for wolves.

Connectivity modeling has become a sophisticated science. Tools like GECOT use algorithms to identify optimal corridor placements, balancing ecological effectiveness with economic feasibility. These models account for terrain, existing land use, cumulative effects between conservation actions, and species-specific movement patterns.

Not all corridors work the same way. Some are physical habitat strips. Others are stepping-stone networks - a chain of protected patches close enough that animals can hop between them. Still others are seasonal routes that animals use during migration. The Pronghorn migration corridor in Wyoming, for instance, protects a specific path that pronghorn have used for thousands of years, rather than creating new habitat.

Research shows corridors deliver measurable results. A study tracking Florida panthers found that connectivity zones reduced isolation and increased genetic exchange between populations. Banff National Park's wildlife crossings have been used by elk, deer, bears, wolves, and cougars, demonstrating that well-designed infrastructure works for multiple species simultaneously.

But corridors aren't risk-free. They can facilitate the spread of diseases and invasive species. A corridor that connects two populations also connects their pathogens. Careful monitoring is essential to catch problems before they cascade.

Here's the paradox: we need to reconnect habitats that roads and cities fragmented, but we can't exactly tear down Interstate 90. Enter wildlife crossing structures - overpasses and underpasses specifically designed to let animals safely traverse human infrastructure.

The gold standard is Banff National Park's Trans-Canada Highway crossings. Since the 1980s, Parks Canada has installed over 44 wildlife crossing structures. The results exceeded expectations: an 80% reduction in wildlife-vehicle collisions on that stretch of highway. Camera traps captured elk, grizzly bears, black bears, wolves, cougars, and wolverines using the structures. Even lynx, notoriously shy animals, crossed.

What makes these structures work? Design details matter immensely. Overpasses need to be wide enough that animals don't feel exposed - typically 50 meters or more. Native vegetation on the crossing surface creates familiarity. Underpasses require sufficient height and light penetration so animals don't perceive them as tunnels. Fencing guides animals toward crossings and away from road surfaces.

"Wildlife corridors serve as nature's bridges that reconnect isolated patches of habitat, enabling genetic exchange and seasonal migrations that sustain healthy populations."

- Conservation biology research consensus

The technology is spreading worldwide. Australia has built specialized rope bridges for koalas. India has installed red chequered highway markings in Madhya Pradesh to create wildlife crossing zones. The Netherlands has over 600 wildlife crossing structures, the highest density in the world, integrated into highway planning from the start.

Climate change adds another wrinkle. Structures built for today's species distribution might be in the wrong place in 30 years. Forward-thinking designs incorporate climate projections, positioning crossings where species are likely to move as temperatures shift, not just where they are now.

Cost-benefit analysis increasingly favors wildlife crossings. A Scioto Analysis study found that crossings generate positive returns by reducing collision costs, insurance claims, and ecological damage. Nevada's Interstate 15 crossings cost $4 million but are projected to prevent $11 million in collision-related expenses over 20 years.

Individual crossing structures are impressive, but some conservationists are thinking far bigger - continent-spanning corridors that reconnect entire bioregions.

The Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative covers 2,100 miles stretching from the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem to Canada's Yukon Territory. Launched in 1993, Y2Y isn't a single park but a network of protected areas, private conservation lands, and crossing structures. Over 25 years, participating partners have secured an 80% increase in protected areas within the corridor. The initiative has facilitated installation of over 100 wildlife crossing structures.

The model works because Y2Y isn't a top-down mandate. It's a coalition of conservation groups, First Nations, ranchers, local governments, and federal agencies. Everyone brings different resources and priorities. Ranchers contribute conservation easements. Indigenous communities bring traditional ecological knowledge and land stewardship. Scientists provide monitoring data. Governments fund crossing infrastructure.

Results are tangible. Grizzly bear populations, once fragmented and declining, now move between protected areas. Wolf packs recolonized portions of their historic range. Genetic studies show increased gene flow in previously isolated populations, exactly what corridor theory predicted.

Europe took a different route to connectivity - literally. The European Green Belt traces the former Iron Curtain from the Barents Sea to the Black Sea. During the Cold War, the militarized border zone became an accidental wildlife refuge. When the curtain fell, conservationists recognized the opportunity: 12,500 kilometers of relatively undeveloped land crossing 24 countries.

Unlike Y2Y, the Green Belt is less wilderness and more mosaic - farms, forests, wetlands, and former military sites. It connects over 40 national parks and protects habitat for rare species like the European otter, black stork, and wildcat. The German portion alone hosts over 1,200 endangered species.

South America's newest initiative aims to connect jaguar populations from Mexico to Argentina. The Continental Jaguar Corridor addresses jaguar habitat fragmentation caused by agriculture, illegal ranching, and roads. Camera trap networks track jaguar movements, revealing critical linkages between protected areas. The challenge is enormous - jaguars need vast territories, and human development has exploded across Latin America.

The Yellowstone to Yukon corridor spans 2,100 miles and has achieved an 80% increase in protected areas over 25 years, with over 100 wildlife crossing structures installed.

What unites these mega-corridors is ambition married to pragmatism. None are pristine wilderness. All incorporate working landscapes, human communities, and existing infrastructure. The vision is coexistence, not exclusion.

Wildlife don't recognize borders. Grizzlies don't stop at the U.S.-Canada line. Jaguars don't check passports crossing from Mexico to Guatemala. But conservation funding, land use laws, and management authority absolutely do recognize borders, creating a governance nightmare.

Y2Y navigates this by operating as a coordinating network rather than a regulatory body. They don't own land or enforce rules. Instead, they facilitate collaboration between entities that do. This requires patient diplomacy - aligning Canadian provincial governments, U.S. federal agencies, tribal nations, and private landowners behind shared goals.

Land acquisition is the trickiest piece. Corridors only work if habitat remains intact, but land ownership is a patchwork. In the U.S., conservation easements offer a middle path - landowners retain ownership but agree to restrictions on development. Y2Y has helped secure hundreds of thousands of acres through easements, working ranches that function as de facto wildlife corridors.

Europe faces different challenges. The Green Belt crosses 24 countries with radically different economies, political systems, and conservation traditions. Some segments are heavily protected; others face development pressure. Coordination happens through the European Green Belt Association, which has no enforcement power but serves as a forum for sharing best practices.

Indigenous land stewardship is becoming central to corridor success. In North America, many corridors cross territories where Indigenous communities hold legal rights or traditional ties. First Nations involvement in Y2Y brings generations of ecological knowledge and legitimate jurisdiction. Unlike colonial conservation models that excluded Indigenous peoples, corridor initiatives increasingly recognize Indigenous leadership as essential, not optional.

Funding remains perpetually tight. Mega-corridors require sustained investment over decades. The U.S. Wildlife Crossings Pilot Program, established in 2021, allocated $350 million for crossing infrastructure, a significant start but nowhere near enough for comprehensive national connectivity. Innovative financing models are emerging - conservation bonds, ecotourism revenue, even biodiversity offset markets - but they're experimental.

Building a corridor is one thing. Proving it works is another. Ecologists use multiple metrics to evaluate corridor effectiveness, and the picture is surprisingly complex.

Wildlife cameras provide the most direct evidence. Banff's crossing structures have been photographed over 200,000 times by 11 species, demonstrating sustained use across a broad community. But camera traps only show that animals are crossing, not whether crossings meaningfully boost populations.

Genetic monitoring offers deeper insight. By comparing DNA from populations on either side of a corridor, researchers can detect gene flow - the ultimate test of connectivity. Studies on Florida panthers and grizzly bears have documented increased genetic diversity in connected populations, evidence that corridors enable breeding across formerly isolated groups.

Population monitoring tracks numbers over time. Are populations growing, stable, or declining? Attributing changes to corridors is tricky because populations respond to many factors - prey availability, disease, hunting pressure. Long-term datasets from Y2Y show grizzly bear populations expanding their range, consistent with corridor theory but not definitive proof.

"Over 25 years, the Yellowstone to Yukon corridor has demonstrated that landscape-scale conservation works - grizzly populations are expanding, gene flow is increasing, and ecosystems are more resilient to climate change."

- Y2Y Conservation Initiative research findings

Collision data provides a clear metric for crossing structures. Where crossings have been installed, wildlife-vehicle collisions measurably drop. Montana's Highway 93 reconstruction included 42 crossing structures and saw an 80% reduction in collisions. Similar patterns appear in Nevada, California, and across Europe.

Emerging technologies are revolutionizing monitoring. GPS collars track individual animal movements in real-time, revealing which landscape features facilitate or block movement. Acoustic monitoring captures bat and bird activity. eDNA sampling detects species presence from water or soil samples without ever seeing an animal.

The challenge is cost. Comprehensive monitoring is expensive, requiring decades of data collection. Many corridor projects lack funding for rigorous evaluation, so effectiveness remains uncertain. A 2023 review found that while corridor theory is well-established, empirical evidence for specific projects is often thin because monitoring wasn't prioritized.

Wildlife corridors aren't cheap. Land acquisition, crossing construction, ongoing management - the bill adds up fast. Critics argue the money could be better spent on other conservation priorities. But economic analysis increasingly shows corridors deliver tangible returns.

Collision reduction saves lives and money. The average wildlife-vehicle collision costs $6,000 in vehicle damage, medical expenses, and carcass removal. Large animals like elk or moose can cause $40,000 in damage and kill drivers. A single wildlife crossing can prevent dozens of collisions annually, recouping construction costs within years.

Ecosystem services provide broader benefits. Connected forests regulate water flow, sequester carbon, and maintain pollinator populations. These services have economic value even if they're not sold in markets. Corridor planning in California incorporates ecosystem service valuations, demonstrating that connectivity benefits extend far beyond wildlife.

Tourism revenue is substantial. Yellowstone generates over $600 million annually in tourism, much of it wildlife-driven. Y2Y markets itself as a wildlife viewing destination, capitalizing on connected ecosystems that support visible megafauna. European Green Belt countries promote eco-tourism along the corridor route.

Avoided costs matter too. When populations collapse, species can become endangered or extinct, triggering expensive recovery programs. Proactive connectivity is cheaper than reactive crisis management. The California condor recovery program has cost over $35 million. Maintaining habitat connectivity might have prevented the collapse for a fraction of that cost.

Innovative financing is emerging. Rewilding Europe's Wilderways initiative seeks private investment in connectivity infrastructure, arguing that restored ecosystems generate returns through tourism, carbon credits, and ecosystem services. It's an experiment in making conservation financially self-sustaining.

But economic arguments have limits. Not everything valuable has a price tag. Intrinsic worth of biodiversity, ethical obligations to other species, cultural connections to wildlife - these don't fit neatly into cost-benefit spreadsheets. The strongest case for corridors combines economic pragmatism with moral conviction.

Climate change transforms corridors from a nice-to-have conservation tool into an existential necessity. As temperatures rise, species must shift their ranges or adapt in place. Most can't adapt fast enough. Movement becomes survival.

Models predict massive range shifts. Boreal species will retreat northward. Alpine species will climb higher. Coastal species will face shrinking habitat as seas rise. Without corridors, these shifts are impossible. A study of European species found that climate corridors could triple the number of species able to track suitable climate conditions.

Corridor design must anticipate future needs, not just current distributions. Wildlife crossing structures built with climate projections place infrastructure where species will move in 2050, even if those areas are currently uninhabited. It's conservation for animals that aren't there yet.

Climate corridors could triple the number of species able to track suitable temperature zones as global temperatures rise, making connectivity essential for climate adaptation.

Altitudinal corridors are particularly critical. In mountainous regions, species can track temperature shifts by moving upslope rather than poleward. The Andes to Amazon corridor protects elevational gradients, enabling species to migrate vertically as lowlands heat up.

Fire regimes are changing, creating new barriers. More frequent megafires fragment forests, destroying habitat and blocking movement. Corridors need to account for fire-adapted species that require connectivity across landscapes shaped by periodic burning. Research suggests that corridors can facilitate post-fire recolonization, accelerating ecosystem recovery.

The feedback loops are complex. Corridors that maintain large mammal populations also maintain the ecological functions those mammals provide - seed dispersal, nutrient cycling, vegetation structure. These functions enhance ecosystem resilience to climate impacts, creating positive feedback where connectivity begets stability.

The corridor movement has momentum, but it's nowhere near the scale needed. A 2025 study estimated that protecting 30% of Earth's land by 2030 - a global conservation target - requires massive expansion of connectivity infrastructure. Current efforts cover a fraction of that.

Policy frameworks are evolving. The U.S. Wildlife Corridors Conservation Act would create a national corridor strategy, coordinating federal land management with state and private efforts. Similar initiatives are emerging in Canada, the EU, and Australia. But legislation moves slowly, and implementation lags further behind.

Technology offers accelerating returns. AI-powered connectivity modeling can analyze vast datasets - satellite imagery, GPS collar data, climate projections - to identify optimal corridor placements faster and more accurately than traditional methods. Machine learning detects patterns humans miss, revealing non-obvious connectivity pathways.

Private sector engagement is growing. Rewilding Europe has attracted corporate sponsors who see brand value in conservation. Carbon markets could fund corridor creation if forest connectivity projects qualify for credits. It's early, but the trend suggests conservation might tap private capital at scale.

The ultimate challenge is cultural. Corridors require humans to share space with wildlife, accept some risk, and subordinate short-term economic gains to long-term ecological health. That's a hard sell in societies oriented toward growth and control. Success stories help - when people see grizzlies return, collisions drop, and ecosystems flourish, support grows.

Indigenous leadership offers a different paradigm. Rather than nature as separate from humans, Indigenous perspectives see humans as part of ecological communities. Corridors designed through this lens aren't about keeping nature "over there" but about restoring relationship and reciprocity. As Indigenous land management expands, corridor initiatives increasingly reflect these values.

Wildlife corridors are simultaneously simple and audacious. The idea - connect fragmented habitats - is straightforward. The execution - coordinating governments, acquiring land, building infrastructure, monitoring results, adapting to climate change, all across decades and borders - is staggeringly complex.

But the alternative is clear. Without connectivity, fragmented populations blink out one by one. Ecosystems unravel. The planet becomes a museum of isolated remnants rather than a living, breathing whole.

The question facing this generation isn't whether we can afford to build corridors. It's whether we can afford not to. Every overpass that guides a grizzly safely across a highway, every protected migration route that lets pronghorn follow ancient paths, every multinational agreement that connects parks across borders - these are investments in a future where wildness persists not despite human presence but woven through it.

The corridors themselves are just infrastructure. What they represent is a choice: to live on a planet where nature has room to move, adapt, and endure. That's not just conservation. It's deciding what kind of world we want to inhabit.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

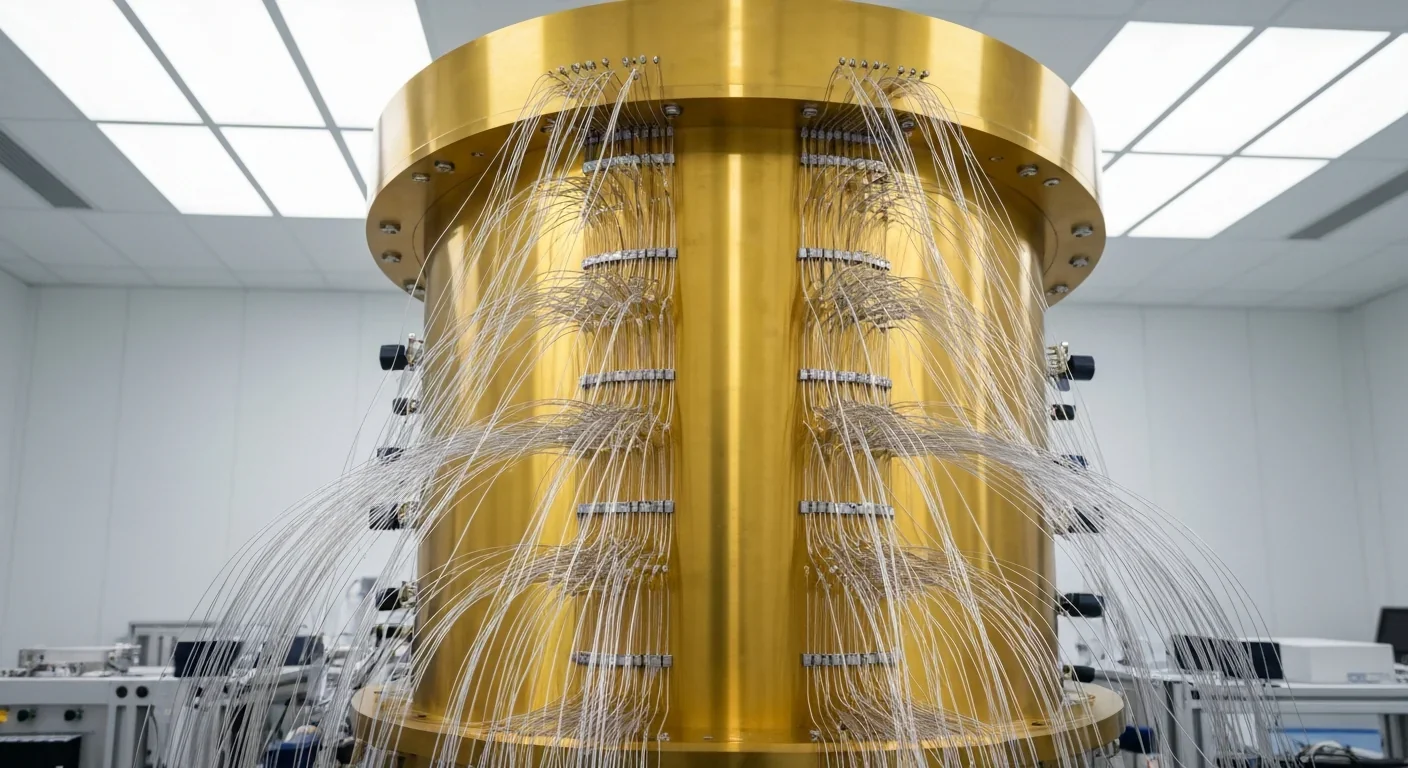

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.