3D-Printed Coral Reefs: Can We Engineer Marine Recovery?

TL;DR: Agroforestry - integrating trees into farming - is transforming agriculture by boosting farm profits up to 400%, sequestering carbon, and rebuilding ecosystems. With the market projected to hit $212 billion by 2034, farmers worldwide are discovering that working with nature instead of against it isn't just sustainable - it's spectacularly profitable.

Imagine walking through a farm where rows of maize grow beneath the canopy of nitrogen-fixing acacias, where livestock graze in the shade of fruit trees, and where every inch of land serves multiple purposes at once. This isn't some futuristic fantasy. It's agroforestry, and it's quietly transforming agriculture from a climate problem into a climate solution.

By 2034, the global agroforestry market is projected to reach $212 billion, driven by farmers who've discovered that mixing trees with crops isn't just good for the planet - it's spectacularly good for business. The numbers tell a compelling story: farms that integrate trees report up to 400% increases in productivity, better drought resistance, and new income streams from timber, fruits, and even carbon credits. Meanwhile, these same systems sequester carbon, rebuild degraded soils, and create biodiversity hotspots in landscapes that once supported nothing but monocultures.

Agroforestry isn't new. Indigenous communities across six continents have practiced it for millennia, understanding intuitively what science is only now quantifying. The Rainforest Alliance notes that traditional systems like Mexico's milpa - where maize, beans, and squash grow alongside trees - have sustained communities for over 4,000 years without depleting soil fertility.

What's changed is our ability to measure the benefits and adapt these practices to modern commercial agriculture. When European colonial powers pushed monoculture farming worldwide, they dismissed tree-based systems as primitive. That was a catastrophic mistake we're only now reversing.

Today's agroforestry movement combines traditional ecological knowledge with cutting-edge science. Researchers can now explain precisely why silvopasture systems - where trees, forage, and livestock coexist - produce more protein per acre than conventional ranching while sequestering up to 15 tons of carbon per hectare annually. They understand the mycorrhizal networks that allow trees to share nutrients with crops, the microclimatic effects that reduce water stress, and the biological pest control that emerges when you restore ecological complexity.

The historical parallel is striking. Just as the Green Revolution of the 1960s dramatically increased yields through synthetic inputs, today's agroforestry revolution is increasing productivity through ecological intelligence. But unlike the Green Revolution, which created long-term problems - soil degradation, aquifer depletion, biodiversity collapse - agroforestry addresses those very problems while maintaining or increasing yields.

The magic of agroforestry lies in what ecologists call "niche differentiation." Trees and crops don't compete; they complement. Deep tree roots access water and nutrients beyond the reach of shallow-rooted crops. Nitrogen-fixing trees like Leucaena or Gliricidia can add 100-200 kg of nitrogen per hectare annually - equivalent to several bags of expensive fertilizer. Tree canopies create microclimates that reduce temperature extremes, with studies showing soil temperatures up to 10°C cooler under tree shade during summer months.

The carbon story is even more compelling. A recent study published in MDPI's Land journal found that well-designed agroforestry systems store substantial carbon while maintaining agricultural productivity. While they may store slightly less carbon than full reforestation, they offer something reforestation can't: continued food production and farmer livelihoods.

Silvopasture systems demonstrate the principle beautifully. Research shows these integrated tree-livestock-forage systems act as carbon sinks that sequester more carbon than monoculture forests or pastures of similar density. The trees provide shade that reduces heat stress in livestock - improving weight gain and milk production - while their roots prevent soil erosion and their leaves provide supplementary fodder during dry seasons.

The biodiversity benefits cascade through the ecosystem. Studies on agroforestry and biodiversity show these systems support 5-10 times more bird species than monocultures, create habitat corridors that allow wildlife movement across fragmented landscapes, and host populations of beneficial insects that provide natural pest control worth thousands of dollars per hectare in avoided pesticide costs.

Here's where agroforestry stops being an environmental feel-good story and becomes a hard-nosed business decision. Farmers practicing agroforestry typically generate income from 3-7 different sources on the same piece of land. This isn't theoretical - it's happening right now across the globe.

In Kenya, smallholder farmers working with Vi Agroforestry report income increases of 50-300% within five years of adopting tree-based systems. They're selling timber from fast-growing species like Grevillea, fruits from mango and avocado trees, fodder from pruned tree branches, and still harvesting their traditional crops from the same fields.

The seven economic benefits outlined by agricultural consultants include risk mitigation that matters enormously in an era of climate volatility. When drought decimates annual crops, fruit trees keep producing. When market prices crash for one commodity, farmers have others to fall back on. This diversification provides a financial cushion that conventional farmers simply don't have.

Then there's the carbon credit revolution. Farm Africa's work in eastern Kenya shows how agroforestry and carbon markets are transforming rural livelihoods. Farmers are earning $30-120 per hectare annually by selling carbon credits generated through their tree-planting efforts. For smallholders earning a few thousand dollars a year, this represents meaningful additional income.

The payback timeline deserves mention. Yes, establishing agroforestry requires upfront investment - tree seedlings, fencing for silvopasture, training - and typical payback periods run 3-6 years. But that's faster than many agricultural investments, and unlike machinery that depreciates, trees appreciate in value. A timber tree planted today might be worth $50 at harvest in 15 years, while simultaneously providing shade, soil improvement, and fodder benefits throughout its growth.

The beauty of agroforestry is its flexibility. There's no single blueprint; systems get designed around local conditions, farmer goals, and market opportunities. But certain principles and practices have proven successful across diverse contexts.

Alley cropping is perhaps the most straightforward entry point. Farmers plant rows of trees with wide alleys between them where they grow annual crops. The trees might be timber species like black walnut, fruit trees like pecans, or nitrogen-fixers like black locust. As trees mature, the alleys narrow, but by then the trees provide additional income. USDA's Climate-Smart Agriculture resources provide detailed guidance on spacing, species selection, and management for different US regions.

Silvopasture suits livestock operations. The transition is gradual: existing pastures get planted with appropriate tree species at densities of 25-100 trees per acre, or existing woodlands get thinned and seeded with improved forages. Forrest Keeling Nursery notes that numerous grants now support these conversions, offsetting establishment costs.

Forest farming involves cultivating high-value specialty crops under existing forest canopies - mushrooms, ginseng, ferns, or medicinal plants. This turns low-productivity woodlots into income-generating assets without clear-cutting.

Species selection requires matching trees to your goals, climate, and soils. Nitrogen-fixing trees like Alnus nepalensis used in Eastern Himalayan systems improve soil fertility while providing fodder. Fruit and nut trees generate marketable products. Timber species like walnut or mahogany appreciate substantially over 15-25 years. Multi-purpose trees do several jobs simultaneously.

The Kickstart Agroforestry guide for Northeastern US farmers emphasizes starting small. Convert one field, learn the system, then expand. Mistakes on two acres are educational; mistakes on 50 acres are expensive.

Maintenance differs from conventional farming but isn't necessarily more labor-intensive. Trees need protection from livestock when young - temporary fencing handles this. Pruning provides fodder and prevents excessive shading. But once established, trees largely care for themselves while annual crops still require full attention.

Even cold climates can work. Syntropic agroforestry in temperate regions uses dense plantings of cold-hardy species, strategic pruning, and succession planning to create productive systems in places previously considered unsuitable. Farmers in Vermont and Minnesota are harvesting chestnuts, hazelnuts, and timber alongside vegetables and grains.

Government support for agroforestry has reached unprecedented levels, though recent political shifts threaten some programs. USDA's Expanding Agroforestry Project was providing technical assistance and cost-share funding before budget cuts raised uncertainty about its future.

The threat is real. Civil Eats reported in April 2025 that federal cuts are stymying agroforestry projects across the US, leaving farmers who'd planned expansions in limbo. This highlights the vulnerability of programs dependent on political winds.

Still, multiple funding streams persist. The Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) offers cost-share payments for agroforestry establishment. Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP) provides annual payments for maintaining practices. State programs add another layer - many states offer tax breaks for forest management plans that include agroforestry components.

Research on policy and financial support identifies market opportunities as potentially more stable than government programs. Carbon markets, certification programs for sustainable products, and premium markets for agroforestry-grown foods create private-sector incentives less subject to political volatility.

The carbon credit dimension is expanding rapidly. Solidaridad Network's analysis shows how smallholder farmers can access these markets, though transaction costs and verification requirements remain barriers. DeepRoots' guide to carbon income explains the process: establish qualifying practices, work with aggregators who bundle small farms into sellable carbon credits, receive annual payments based on verified sequestration.

Bloomberg NEF's insights on agricultural carbon markets suggest these markets will grow substantially, potentially reaching $40 billion globally by 2030. For farmers, this could mean $50-150 per hectare in annual carbon revenue on top of traditional agricultural income.

Internationally, programs vary widely. Kenya's farmer field schools, supported by research showing they promote livelihood diversification, combine training with micro-credit for tree seedlings. The FAO's COP29 statements positioned agrifood systems transformation - including agroforestry - as central to meeting climate commitments.

Agroforestry isn't a silver bullet, and pretending otherwise does farmers no favors. Real barriers exist, some technical, others systemic.

The time lag between investment and return frustrates farmers accustomed to annual crop cycles. Planting trees means betting on the future, and farmers facing debt or uncertain land tenure struggle with that timeline. This is where policy matters: long-term leases, inheritance protections, and upfront subsidies can make the economics work.

Knowledge gaps are significant. Research on farmer perceptions in Ethiopia found that lack of technical knowledge was the primary barrier to adoption. Extension services in many regions remain focused on conventional agriculture; agroforestry expertise is scarce. Farmers often learn through trial and error, which works but slows adoption.

Market access for tree products can be challenging. A farmer can grow 500 kilos of specialty mushrooms under their forest canopy, but without buyers willing to pay premium prices, it's pointless. Developing market connections requires time and networks many farmers lack.

Equipment compatibility presents practical issues. Standard farm machinery works in clean fields, not among tree rows. Farmers adapt - using smaller equipment, adjusting row spacing, or accepting more hand labor - but these adjustments add costs and complexity.

Land tenure insecurity particularly affects smallholders in developing countries. Why plant trees you'll harvest in 15 years if you might lose access to the land next year? Studies in Senegal show secure land rights dramatically increase climate-smart agriculture adoption, including agroforestry.

The carbon credit promise also comes with caveats. Pure Advantage's analysis of carbon sequestration cautions that not all agroforestry systems qualify for credits, verification costs can be prohibitive for small operations, and permanence requirements - proving trees won't be cut for decades - exclude some farmers. The Mongabay report comparing agroforestry and reforestation for carbon storage reminds us that pure forests sequester more carbon, so carbon-focused programs may favor reforestation over agroforestry despite the latter's multiple benefits.

Kenya has emerged as an agroforestry powerhouse. Farmonaut's review of Kenyan systems documents widespread adoption driven by NGOs, government support, and farmer-to-farmer learning. The combination of practical training, seedling distribution, and carbon finance has created a virtuous cycle. Farmers see neighbors prospering with trees and follow suit.

The Himalayan regions offer different lessons. Research on tree-crop interactions in Nepal shows sophisticated multi-story systems where Alnus nepalensis fixes nitrogen at the canopy level, shade-tolerant crops grow in the middle layer, and shade-demanding vegetables occupy the ground level. These vertically integrated systems produce more biomass and revenue per hectare than any single-layer approach.

Latin America's experience with regenerative agriculture and tree planting highlights the social dimensions. Community-based approaches where groups of farmers adopt practices together show higher success rates than individual efforts. Collective marketing, shared equipment, and peer learning overcome barriers that stop individual farmers.

Europe's agroforestry renaissance focuses on high-value timber species integrated with organic farming. The premium markets for organic products provide revenue during the 15-25 years timber trees mature. Strict environmental regulations make the pollution-prevention benefits of agroforestry particularly valuable.

The CIFOR-ICRAF's best practices compilation synthesizes lessons from tropical landscapes globally. Key insights include the importance of farmer participation in design - top-down systems fail; farmer-designed systems succeed - and the need to match expectations to ecological reality. Not every tree thrives everywhere; local knowledge matters enormously.

Indigenous networks are reclaiming their traditional practices and adapting them. The Indigenous Agroforestry Network supported by Ecotrust combines traditional knowledge with modern market access, creating economically viable systems that honor cultural values. This isn't nostalgia; it's recognizing that Indigenous communities developed agroforestry systems optimized for resilience over millennia, and that knowledge is invaluable.

For farmers considering agroforestry, the path forward is clearer than ever. Start with education - online courses, field days, consultations with agroforestry specialists. The learning curve is real, but resources abound.

Assess your specific situation honestly. What are your goals? Income diversification, carbon sequestration, livestock welfare, soil improvement? Different systems serve different goals. What constraints do you face? Climate, soil type, water availability, labor, capital? Choose systems compatible with your resources.

Start small and strategic. Convert your worst-performing field first - the eroded slope, the drought-prone section, the area too wet for conventional crops. Trees might thrive exactly where annual crops struggle. This minimizes risk while you learn.

Seek out government programs while they exist. The grants for tree planting projects can cover 50-75% of establishment costs. Apply early; funds run out.

Connect with other practitioners. Farmer networks provide the real-world knowledge that research papers can't capture - which species actually work in your climate, where to source quality seedlings, which markets pay premium prices for your tree products. This tribal knowledge is gold.

Think in generations. The trees you plant may not reach peak value in your farming career, but they'll benefit your children or the next landowner. The soil you build through decades of tree-root cycling and nitrogen fixation becomes a legacy. This long-term thinking runs counter to quarterly earnings culture, but it's how lasting agricultural wealth gets built.

For consumers and policymakers, supporting agroforestry means buying products from these systems when possible - paying the premium for agroforestry coffee or shade-grown chocolate. It means advocating for stable, long-term policy support rather than programs that appear and disappear with elections. It means recognizing that the cheapest food often carries hidden costs in degraded ecosystems and that systems which rebuild natural capital while feeding us deserve financial support.

Agroforestry represents more than an agricultural technique - it's a philosophical shift. For 150 years, industrial agriculture has treated nature as something to dominate, simplify, and control. Agroforestry succeeds by cooperating with ecological processes, embracing complexity, and recognizing that nature's systems, refined over millions of years, often outperform our reductive models.

The sustainable agriculture practices review emphasizes this paradigm shift. Soil health, climate resilience, and productivity aren't competing goals in ecological systems - they're mutually reinforcing. The same practices that capture carbon also improve water infiltration, reduce erosion, and increase yields under stress conditions.

The market is responding. That projected $212 billion agroforestry market by 2034 reflects growing demand for sustainably produced food, carbon credits, certified timber, and specialty crops that only agroforestry systems can supply at scale. Persistence Market Research's analysis shows compound annual growth rates of 8-10%, driven by climate commitments, corporate sustainability goals, and consumer preferences.

But adoption rates remain frustratingly low. Globally, agroforestry covers perhaps 10% of agricultural land, with enormous regional variation. Scaling to 30-40% over the next two decades - what's needed to significantly impact climate and biodiversity goals - requires removing the barriers holding farmers back.

The ten regenerative agriculture practices that growers should follow include agroforestry prominently, but also cover cropping, reduced tillage, and integrated livestock. The most resilient farms combine multiple practices, creating synergies. Trees plus cover crops plus rotational grazing produces better outcomes than any single practice alone.

The case for agroforestry is overwhelming. Economically, it diversifies income and reduces risk. Environmentally, it sequesters carbon, rebuilds soils, conserves water, and creates habitat. Socially, it provides stable livelihoods and preserves cultural knowledge. The question isn't whether agroforestry should expand, but how quickly we can make it happen.

The barriers are real but surmountable. Policy support, accessible financing, technical assistance, market development - these are solvable problems if we prioritize solutions. The knowledge exists; successful models operate worldwide; farmer demand is growing.

What's needed is commitment - from governments to fund programs despite budget pressures, from researchers to translate science into practice, from businesses to buy agroforestry products and pay fair prices, from farmers to take the long view and plant trees.

The coming agricultural transformation will be complex and contested. But every transformed farm demonstrates that food production and ecosystem restoration aren't opposites. They're partners. And the farms that grasp this reality aren't just surviving - they're thriving, sequestering carbon, nurturing biodiversity, and building soil that will feed generations.

Agroforestry isn't the complete answer to agriculture's sustainability crisis, but it's a major piece of the solution. For farmers willing to think in decades rather than seasons, to work with nature rather than against it, the opportunities are enormous. The trees they plant today will shade their grandchildren and capture carbon long after we're gone. That's not romantic idealism - it's practical climate action with a profit motive.

The question is simple: will we plant the trees?

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

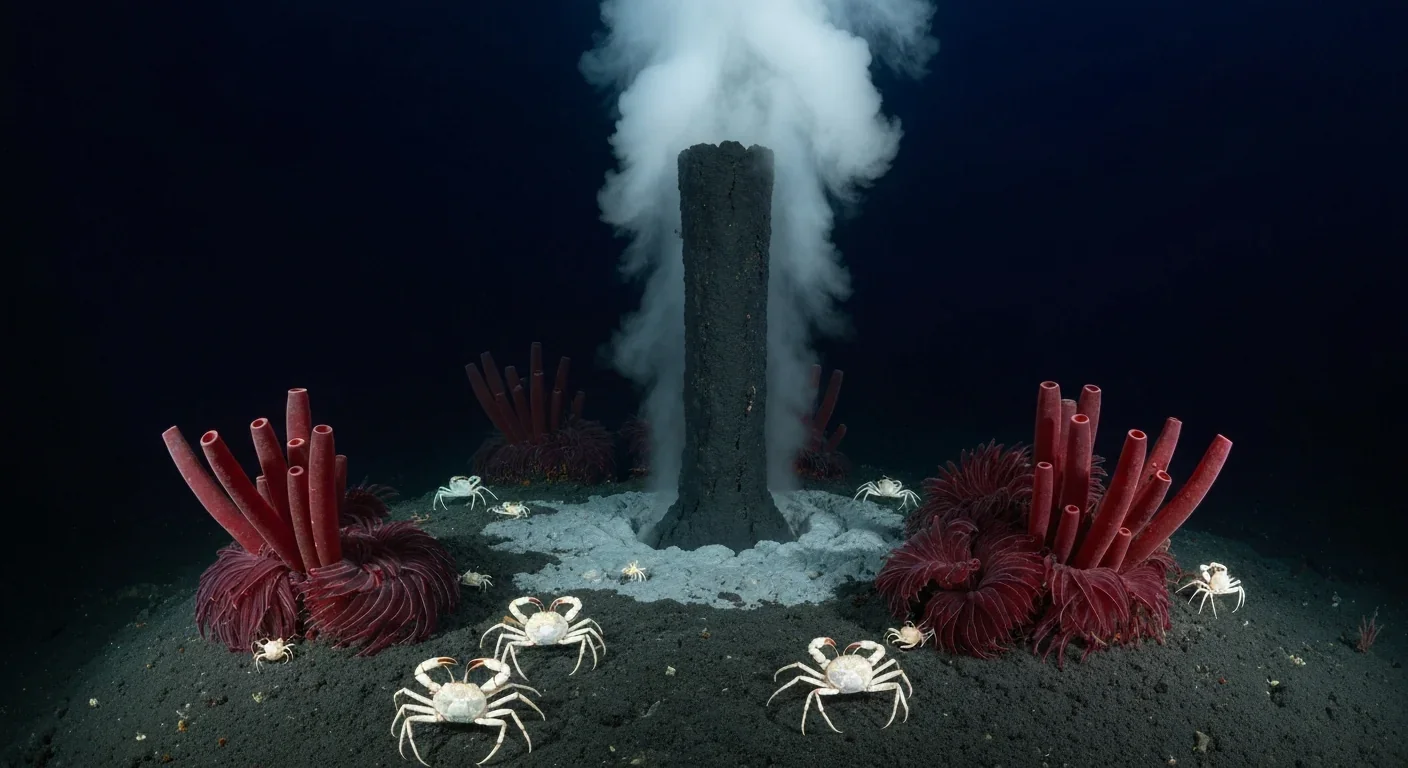

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

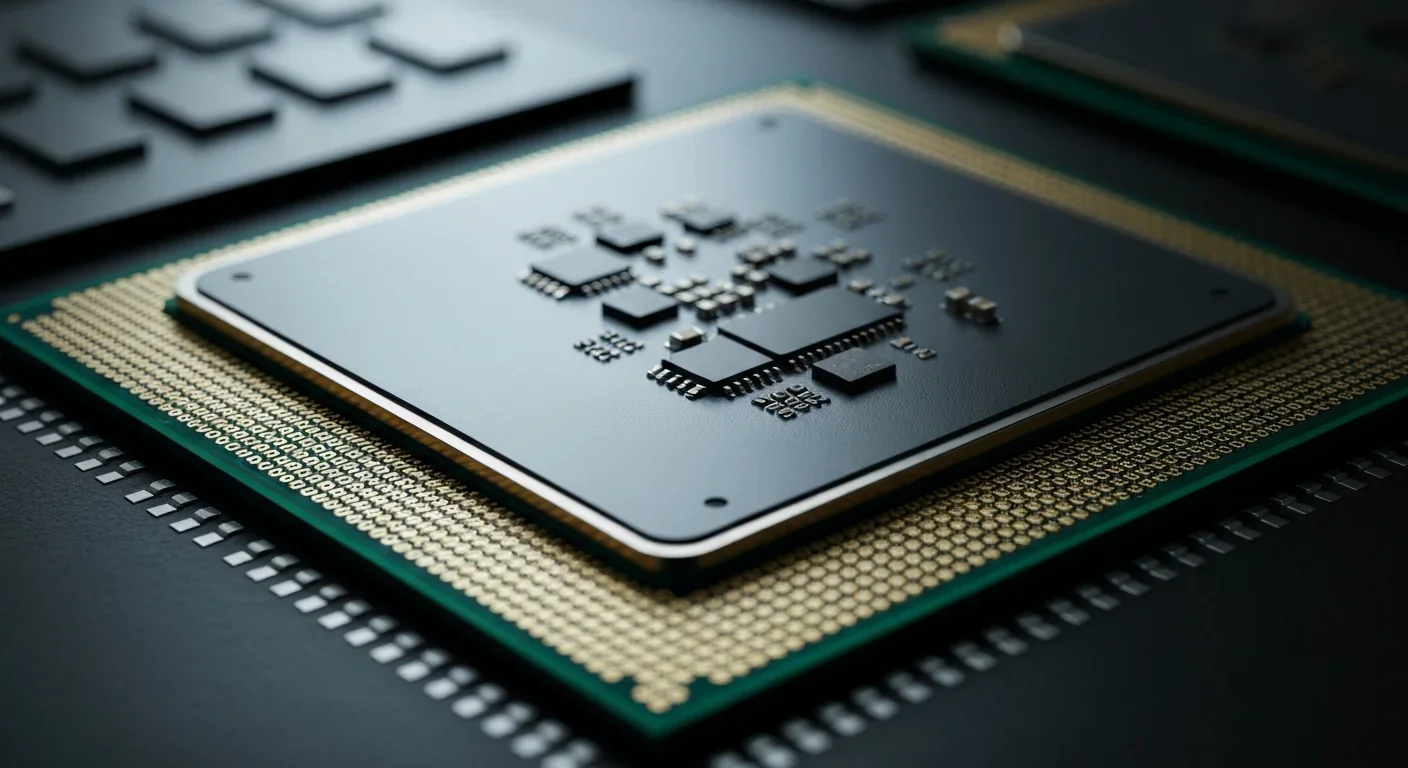

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.