AI Cameras Save Sea Turtles in Fishing Nets

TL;DR: Agroforestry - integrating trees with crops and livestock - is emerging as agriculture's most practical answer to climate chaos. It makes farms more resilient to extreme weather, sequesters carbon, diversifies income, and proves profitable long-term, though policy support and technical knowledge remain critical barriers to widespread adoption.

By 2030, scientists predict agriculture will face its greatest reckoning yet. Not from market crashes or policy shifts, but from weather that refuses to follow patterns farmers have relied on for generations. Droughts linger where rain once fell. Floods swallow fields that stayed dry for decades. Heat waves turn productive cropland into dust. The question isn't whether conventional farming can survive this chaos - it's what replaces it when it can't.

The answer might be simpler than anyone expected: plant more trees.

Agroforestry, the practice of integrating trees with crops and livestock, is emerging as agriculture's best bet against climate chaos. Not because it's new - indigenous farmers have done this for millennia - but because the science now proves what traditional knowledge always knew. Trees don't just stand there looking pretty. They regulate temperature, capture carbon, hold water in soil, break wind, diversify income, and transform vulnerable monocultures into resilient ecosystems.

And they're profitable. That's the part that makes farmers actually pay attention.

Here's what conventional agriculture is up against: extreme weather events are intensifying across every growing region on Earth. The FAO's latest report confirms what farmers already feel in their bones - predictable growing seasons are becoming historical artifacts.

A monoculture corn farm in Iowa has exactly one defense against a three-week drought: irrigation, if the aquifer hasn't run dry. A soybean field in Brazil facing unseasonable frost can't adapt mid-season. These systems optimized for efficiency under stable conditions become catastrophically fragile when conditions stop being stable.

Agroforestry systems flip that equation. Instead of betting everything on a single crop's tolerance range, farmers create layered systems where different species buffer each other against extremes. When drought hits, tree roots reach water that annual crops can't access, then share it through mycorrhizal networks. When heat spikes, tree canopies create microclimates up to 5°C cooler than open fields. When storms arrive, windbreaks reduce wind speed by 50% for distances up to 20 times the trees' height.

Tree canopies create microclimates up to 5°C cooler than open fields - a critical buffer as extreme heat events intensify globally.

The resilience isn't theoretical. In the Indian Himalayas, researchers documented agroforestry systems storing 21.35 metric tons of carbon per hectare - 51% more than conventional agriculture plots. But carbon storage was almost secondary to the practical benefits farmers observed: crops surviving droughts that killed neighbors' fields, soil that held moisture weeks longer, yields that stayed consistent when others crashed.

Understanding agroforestry means forgetting the mental image of neat tree rows in an orchard. This is agriculture reimagined as ecosystem management.

Take silvopasture, the practice of integrating trees into grazing land. In Wisconsin, dairy farmers are planting oaks and chestnuts in pastures where cattle graze. The trees provide shade that reduces heat stress - dairy cows produce significantly more milk when they're not panting through 35°C afternoons. The cattle fertilize the trees and control weeds. The system sequesters more carbon than forests or pastures alone while producing both timber and dairy products.

Or consider alley cropping, where farmers plant rows of trees with crops growing in the alleys between them. In Mexico, traditional agroforestry systems using this approach produce 15% higher crop yields than modern monoculture techniques. The trees fix nitrogen, reducing fertilizer needs. Their roots prevent erosion on slopes. Their leaves become mulch that builds soil organic matter. And every 10-20 years, farmers harvest timber or fruit from the tree rows, creating income streams that annual crops can't match.

Agroforestry isn't a single practice but a toolkit of approaches tailored to different regions, climates, and farm types. Forest farming produces shade-tolerant crops like mushrooms or ginseng under tree canopies. Riparian buffers filter runoff and prevent stream erosion while producing berries or nuts. Windbreaks protect fields and create wildlife corridors. What they share is intentional complexity that makes entire farm systems more resilient than the sum of their parts.

The water management alone justifies the transition in many regions. Tree roots create channels that increase water infiltration - the rate at which rainfall soaks into soil rather than running off. They improve soil structure, creating spaces that hold moisture accessible to crop roots during dry spells. In drought-prone areas, agroforestry systems maintain crop survival rates that would be impossible in bare-soil agriculture.

Climate benefits mean nothing if farmers can't pay their bills. The economic case for agroforestry was murky until recently because initial costs are real and returns take time. Planting trees, waiting for them to mature, learning new management techniques - these require investments that conventional farming doesn't.

But the long-term math tells a different story.

Small-scale American farmers who adopt agroforestry report income diversification that insulates them from market volatility. When corn prices crash, timber values might rise. When drought reduces annual crop yields, nut production from established trees provides cash flow. One farmer described it as "not putting all your eggs in one basket, or all your cash in one crop season."

"Not putting all your eggs in one basket, or all your cash in one crop season."

- American agroforestry farmer on income diversification

The profitability comparison depends heavily on timeframe and measurement. Year one? Conventional farming wins on cash flow because there's no establishment cost and immediate production. Year ten? Agroforestry systems start pulling ahead because input costs drop (less fertilizer, less irrigation, less pesticide) while new revenue streams emerge from tree products. Year thirty? The conventional farm has extracted nutrients from soil that now requires constant life support, while the agroforestry system has built fertility that compounds productivity.

Wisconsin farmers integrating silvopasture improve water quality and environmental outcomes compared to conventional woodland grazing, and they see higher profits from combined timber-livestock operations. The initial skepticism about managing both trees and animals has given way to recognition that the systems work together synergistically.

The economic risks can't be ignored, though. Tree establishment requires upfront capital that many farmers don't have. Returns on timber take 15-30 years depending on species. Knowledge gaps about optimal spacing, species selection, and management timing create uncertainty. Land tenure issues complicate decisions - why plant trees you won't harvest if the lease ends in five years?

This is where policy support becomes critical.

For decades, agricultural policy was designed for monocultures. Subsidies rewarded corn and soy planted fence-row to fence-row. Crop insurance covered annual plantings but not perennial systems. Technical assistance focused on maximizing yields of single crops, not managing integrated tree-crop systems.

That's changing, though not fast enough for farmers who need help now.

The USDA now offers multiple grant programs specifically supporting agroforestry. The Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) provides cost-share funding for tree planting and establishment. The Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP) rewards farmers who adopt agroforestry practices with annual payments. Regional conservation partnerships direct millions toward agroforestry projects, particularly in watersheds where water quality is critical.

Organizations are compiling grant directories to help farmers navigate funding opportunities. State-level programs complement federal support - some states offer property tax reductions for land enrolled in agroforestry systems. Others provide free technical assistance through extension services specialized in tree-crop integration.

But significant policy barriers remain. In Ethiopia, where smallholder farmers could benefit enormously from agroforestry, perceptions about adoption barriers include unclear land rights, lack of institutional support, and limited access to markets for tree products. These challenges echo globally - the policy framework hasn't caught up to the agronomic reality that trees belong on working farms.

Payments for ecosystem services can transform economics: immediate cash flow for carbon storage and water quality improvements replaces the 10-year wait for timber revenue.

Payments for ecosystem services (PES) schemes offer one solution. Governments can compensate farmers for carbon sequestration, water quality improvements, and biodiversity conservation that agroforestry provides. When farmers receive payment for storing carbon in trees and soil, the economics shift dramatically. What looked like a 10-year wait for timber revenue becomes immediate cash flow from ecosystem services.

The current agroforestry resurgence isn't inventing something new. It's rediscovering what indigenous farmers never stopped practicing.

In Mexico, traditional milpa systems interplant corn, beans, squash, and trees in patterns refined over thousands of years. In India, farmers grow crops under coconut palms, beneath which they cultivate pepper vines, with pineapple filling ground space. In Africa, the practice of "farmer-managed natural regeneration" allows native trees to regrow in fields, creating parkland systems where crops grow between scattered trees.

These systems survived not because of subsidy programs or scientific validation, but because they worked. They fed families through droughts and floods, built soil fertility without purchased inputs, provided timber and medicine, and created landscapes that supported both people and biodiversity.

Modern agroforestry takes these time-tested approaches and adds scientific understanding of why they work. Climate-smart agriculture integrates indigenous knowledge with current research, measuring carbon flows, quantifying microclimate effects, optimizing species combinations for different soil types and rainfall patterns.

Training programs now bridge traditional and modern approaches. The Savanna Institute offers on-farm workshops where farmers learn agroforestry design principles, then adapt them to their specific contexts. Virginia Tech runs capacity-building programs that help farmers transition conventional operations to integrated tree-crop systems.

The innovation isn't in the basic concept - it's in the implementation details. Which tree species pair best with which crops in which climate zones? How do you manage timing so that tree root competition doesn't suppress early crop growth? What spacing maximizes both crop yield and tree growth? These questions get answered through farmer experimentation supported by research validation.

Understanding agroforestry abstractly is one thing. Seeing it work on actual farms is what convinces skeptics.

In rural Appalachia, farmers are integrating forest farming into existing woodlots, growing high-value crops like ginseng, mushrooms, and goldenseal under tree canopies. These forest products generate income from land that would otherwise produce nothing until timber harvest. The diversified income helps keep families on farms during tough years.

Mediterranean farmers facing increasingly severe droughts are adopting climate-smart interventions that include agroforestry. Almond groves interplanted with drought-tolerant shrubs and cover crops show better water-use efficiency and soil health than conventional orchard systems.

"Agroforestry is a flexible and adaptable approach that can be tailored to diverse contexts and challenges."

- Sustainability researcher on system versatility

Case studies from around the world reveal common patterns. Initial skepticism gives way to enthusiasm once farmers see results. Community knowledge-sharing accelerates adoption - when one farmer succeeds, neighbors start experimenting. Technical support matters enormously during establishment years. And economic viability depends on identifying marketable products from the tree component.

One particularly compelling example comes from semi-arid regions where biodiversity-friendly farming combines agroforestry with native species conservation. Farmers plant native trees that provide habitat for pollinators and natural pest predators while producing food or timber. The resulting systems require fewer pesticides, support higher biodiversity, and prove more resilient to climate variability.

So a farmer decides to try agroforestry. What actually happens?

First comes planning. Successful systems require upfront design that accounts for existing infrastructure, climate patterns, market access, and long-term goals. What are you trying to produce? What problems are you trying to solve? How much land can you dedicate to trees without compromising short-term income?

Species selection depends heavily on context. Temperate regions might choose oak, walnut, or chestnut for timber and nuts. Tropical areas could integrate nitrogen-fixing trees like leucaena with annual crops. The decision matrix includes growth rate, market value, climate tolerance, pest resistance, compatibility with existing crops, and maintenance requirements.

Establishment takes serious work. Planting trees, protecting them from livestock or wildlife, managing early competition with crops, irrigation during dry periods - the first three years are labor-intensive. This is when many farmers give up if they don't see immediate benefits or if support systems aren't available.

But once established, management often becomes simpler than conventional farming. Mature agroforestry systems require fewer inputs than annual cropping. Tree mulch replaces purchased fertilizer. Improved water retention reduces irrigation needs. Natural pest management from increased biodiversity reduces pesticide use. The labor shifts from constant intervention to periodic harvesting and maintenance.

The first three years are labor-intensive - but mature agroforestry systems often require fewer inputs than conventional farming, with tree mulch replacing fertilizer and improved water retention reducing irrigation needs.

Technical knowledge matters enormously. Farmers need to understand pruning techniques, optimal spacing, nutrient cycling, pest management for both trees and crops, and timing of operations. Extension services, farmer networks, and training programs fill this knowledge gap.

Market development can't be overlooked. Growing chestnuts is pointless if there's nowhere to sell them. Successful agroforestry adoption requires market linkages for tree products, whether timber mills, nut processors, or specialty crop buyers. Some regions have robust markets; others need infrastructure development.

Individual farm success stories are encouraging. But can agroforestry scale to transform agriculture across entire regions or countries?

The challenges are substantial. Land tenure insecurity prevents long-term tree planting in many parts of the world. Tenant farmers won't invest in trees they won't harvest. Small landholders can't afford the income gap during establishment years without financial support.

Knowledge dissemination at scale requires investment in extension services that most regions lack. Training thousands of farmers in agroforestry design and management means building institutional capacity that doesn't currently exist. Participatory approaches involving local communities work better than top-down mandates, but they're slower and require sustained engagement.

Policy frameworks need comprehensive overhaul. Agricultural subsidies that reward monoculture undermine agroforestry adoption. Crop insurance that doesn't cover perennial systems creates unnecessary risk. Regulations designed for conventional farming sometimes prohibit or complicate tree integration.

Yet the scaling potential is real if barriers get addressed. Regenerative agriculture principles are spreading through farmer networks, NGO programs, and corporate supply chain initiatives. Companies sourcing agricultural commodities increasingly recognize that degraded conventional farms won't meet future demand - they're investing in farmer transitions to more resilient systems.

Regional initiatives demonstrate what's possible. California's climate-smart agriculture program includes agroforestry as a key strategy. The Chesapeake Bay Foundation promotes regenerative agriculture with tree integration to reduce nutrient runoff. State-level policies in Vermont and Oregon support agroforestry expansion.

Here's what makes agroforestry uniquely powerful: it simultaneously addresses climate mitigation and adaptation.

On the mitigation side, trees sequester carbon. Agroforestry systems can store significant amounts in both biomass and soil. The Indian Himalayan research showing 21.35 metric tons of carbon per hectare isn't exceptional - it's typical of well-managed systems. Scale that across millions of hectares and you're talking about meaningful climate impact.

But carbon storage is almost secondary to adaptation benefits. Agroforestry makes farms more resilient to the climate chaos that's already here and getting worse. Drought tolerance, flood resistance, temperature regulation, erosion control - these aren't future benefits, they're immediate farm survival needs.

The systems also enhance biodiversity in agricultural landscapes. Trees provide habitat for birds, beneficial insects, and pollinators that monocultures exclude. This biodiversity delivers ecosystem services - pest control, pollination, nutrient cycling - that conventional farming has to replace with purchased inputs.

Water quality improvements matter for entire watersheds, not just individual farms. Tree buffers filter agricultural runoff, reducing nutrient and sediment pollution in streams and rivers. This benefits downstream communities, ecosystems, and fisheries.

The transition from conventional agriculture to integrated agroforestry systems won't happen overnight. It shouldn't. Farmers need time to learn, experiment, and adapt systems to their specific contexts.

But the direction is clear. Agriculture faces unprecedented climate challenges that monocultures can't handle. Weather volatility will intensify. Extreme events will become normal. Input costs will rise as environmental regulations tighten and resources deplete. Consumer demand for sustainable food production will grow.

Agroforestry offers a pathway through this transition that makes ecological and economic sense. It builds on indigenous knowledge while incorporating modern science. It diversifies farm income while improving environmental outcomes. It sequesters carbon while adapting to climate impacts.

The farmers already doing this aren't waiting for perfect policies or complete scientific certainty. They're planting trees because they've seen neighbors' crops fail while diverse systems survive. They're integrating livestock with forests because profits improve and animals are healthier. They're experimenting with species combinations because the status quo isn't working anymore.

What they need now is support - financial resources for establishment costs, technical knowledge for system design, market connections for tree products, policy frameworks that reward long-term thinking, and recognition that agriculture's future looks more like a forest than a cornfield.

The chaos is coming. Actually, it's already here. The question is whether we'll face it with vulnerable monocultures or resilient ecosystems. Whether we'll keep extracting from soil until it collapses or start building fertility that compounds over decades. Whether we'll treat climate change as something to mitigate later or adapt to right now.

Some farmers are already answering those questions. They're the ones planting trees.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

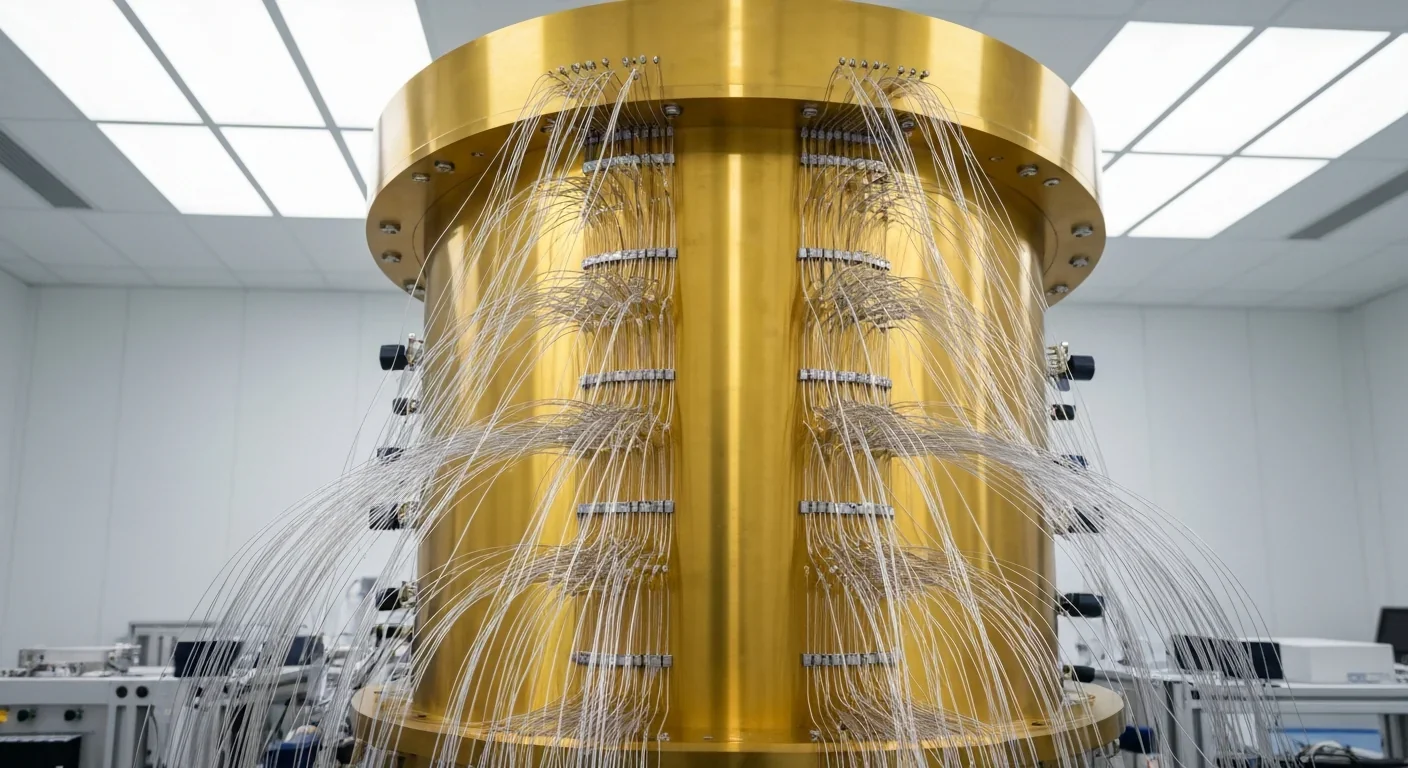

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.