AI Cameras Save Sea Turtles in Fishing Nets

TL;DR: AI-powered sensors and algorithms are transforming farming by enabling precise, data-driven decisions about water, fertilizer, and pesticides. Farms report 33% water savings and up to 80% pesticide reductions while maintaining yields, though adoption barriers - costs, connectivity, and knowledge gaps - remain significant for smaller operations.

In Bihar's rice paddies and California's almond orchards, something remarkable is happening. Farmers are using artificial intelligence algorithms and networks of tiny sensors to make decisions their grandparents would have based on intuition and decades of experience. The result? Water consumption down 33%, pesticide use slashed by up to 75%, and yields climbing year after year. Welcome to precision agriculture - where data replaces guesswork, and every seed, drop of water, and grain of fertilizer goes exactly where it's needed.

The revolution isn't coming. It's already here, quietly transforming how humanity feeds itself.

At its core, precision agriculture combines three powerful tools: sensors that measure everything from soil moisture to insect activity, artificial intelligence that processes these measurements into actionable insights, and automated equipment that applies inputs with surgical precision. Think of it as giving farms a nervous system and a brain.

Drones equipped with multispectral cameras fly over fields capturing images in wavelengths invisible to the human eye. These reveal which plants are stressed, where nitrogen levels are dropping, and which sections need water - often weeks before any visible symptoms appear. On the ground, soil sensors continuously measure moisture, temperature, and nutrient levels, transmitting data in real time to cloud-based AI platforms.

The AI part is where things get interesting. Machine learning models analyze this flood of sensor data alongside weather forecasts, historical yields, and crop growth models to generate remarkably accurate predictions. Some systems achieve R² scores of 0.92 - meaning they can predict crop performance with over 90% accuracy. Temperature emerges as the most critical factor, with complex interactions between rainfall patterns and soil nutrients creating a matrix of variables that would overwhelm any human analyst.

Advanced AI systems achieve over 90% accuracy in predicting crop performance by analyzing temperature, rainfall, soil nutrients, and historical data - a complexity no human could process in real time.

But here's the clever bit: The latest systems use explainable AI techniques like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) that don't just spit out recommendations - they show farmers why. A screen might display: "Apply nitrogen to the northeast quadrant because soil sensors show depletion, the crop growth model predicts demand will peak in 10 days, and historical data shows a 15% yield boost from early application in similar conditions." This transparency helps farmers trust the system and learn from it, blending algorithmic insights with hard-won agricultural expertise.

Traditional farming treats entire fields uniformly. You water everything, fertilize everything, spray everything. It's like prescribing the same medicine to every patient regardless of symptoms. Precision agriculture flips this approach entirely - it manages crops zone by zone, sometimes plant by plant.

Variable rate application systems adjust inputs on the fly as tractors move across fields. A GPS-guided sprayer might apply 100 pounds of fertilizer per acre in one zone, 150 in another struggling with poor soil, and 75 in a naturally fertile section - all during a single pass. The same goes for seeding density, irrigation, and pesticide application.

The results speak for themselves. Farms using variable rate seeding report gains averaging €100 per hectare on operations larger than 150 hectares. That might not sound dramatic, but scaled across thousands of acres and multiple growing seasons, it adds up to substantial competitive advantages. More importantly, the environmental benefits compound year after year.

Consider California's almond orchards, where precision irrigation sensors helped growers cut water consumption by 33% - in a region where every drop matters and climate change is making droughts more frequent. Or the date palm farms in Qatar and the UAE, where AI-powered insect monitoring sensors detect pest infestations three months earlier than conventional scouting, allowing farmers to target treatments before populations explode.

"If you miss the indications of that first generation, you're essentially wasting the insecticide."

- Monique Rivera, Cornell Agritech Professor

Early detection doesn't just save money - it prevents the environmental damage and pesticide resistance that come from repeated blanket spraying.

Here's the uncomfortable truth: Precision agriculture technology requires serious upfront investment. A basic GPS guidance system runs £4,000 to £9,000. Add yield monitors, soil sensors, and drone services, and you're looking at tens of thousands. For sophisticated AI-driven platforms with variable rate controllers and comprehensive sensor suites, costs can exceed £100,000.

This creates an obvious scalability problem. Only 24% of small-scale farms in Kentucky have adopted any precision agriculture technology, according to a 2025 survey of 300 operations. Farm size proves to be a strong predictor of adoption - larger operations can amortize equipment costs across more acres and generate ROI faster.

But the economics aren't quite as simple as "big farms yes, small farms no." The research reveals a more nuanced picture.

Phased adoption strategies help farms of various sizes ease into precision agriculture. Many start with GPS auto-guidance for tractors - relatively affordable, immediately useful for reducing overlap and operator fatigue, and compatible with existing equipment. Once that investment pays off, they add yield monitoring or soil sampling, gradually building toward full integration.

The payback period varies dramatically by crop type, region, and what you're optimizing for. Variable rate nitrogen application typically shows ROI within 2-3 seasons through reduced fertilizer costs and improved yields. Precision irrigation can pay for itself in a single drought year. Pest monitoring systems justify their cost by preventing yield losses that would have been catastrophic.

There's also growing evidence that precision agriculture creates value beyond the immediate financial returns. Farms that can document reduced chemical use and water consumption may qualify for sustainability certifications, access premium markets, or benefit from emerging carbon credit programs. Some insurance companies are beginning to offer lower premiums to operations that use monitoring systems that reduce risk.

If you're imagining fleets of autonomous tractors crisscrossing Iowa cornfields, you're only seeing part of the picture. The real challenge - and opportunity - lies in making these technologies work for the billions of people who farm on a completely different scale.

Smallholder farmers in developing countries face barriers that go far beyond equipment costs. Infrastructure deficits severely restrict precision agriculture adoption in rural areas. Many regions lack reliable internet connectivity for transmitting sensor data, and unstable electricity makes charging drone batteries or running climate-controlled storage for sensitive equipment nearly impossible.

The Kentucky survey data revealed that lack of knowledge about precision agriculture (35% of respondents) and inadequate broadband coverage (20%) were cited as major barriers, even by farmers who could theoretically afford the technology. You can't use cloud-based AI if you don't have cloud access.

Socio-cultural factors matter too, often more than economics. In many agricultural communities, farming practices pass down through generations as closely held wisdom. Trusting an algorithm over grandfather's advice requires a mental shift that some farmers - understandably - resist. Land tenure insecurity creates another obstacle: Why invest in soil monitoring systems if you might not be farming that land in five years? And gender dynamics play a role, as women farmers in many regions face additional barriers to accessing agricultural technology and training.

The biggest barriers to precision agriculture adoption aren't just financial - lack of knowledge (35%), inadequate connectivity (20%), and socio-cultural resistance often matter more than equipment costs.

Yet success stories are emerging from unexpected places. Drone-based crop monitoring projects in India's Indo-Gangetic Plains show that precision agriculture can work in high-yield, high-stress environments typical of developing regions. The image-based insect sensors operating in date palm farms withstand temperatures up to 194°F, proving the technology can be engineered for extreme conditions.

The key seems to be appropriate technology design - solutions built for low-connectivity environments, with interfaces translated into local languages, offering recommendations calibrated to regional crops and farming systems rather than one-size-fits-all approaches developed for Western industrial agriculture.

Every sensor that collects data about soil conditions, every drone that photographs fields, every AI model that processes farming decisions - they all create a digital trail. The question of who owns this data and what they can do with it has become one of the most contentious issues in precision agriculture.

Farmers understandably worry about control. If an agtech company's sensors collect detailed information about yields, input use, and soil quality across your operation, does that data belong to you or to them? Can they sell anonymized versions to competitors? Use it to train AI models they sell to others? Leverage insights to gain advantage in commodity markets?

Data privacy concerns reduce farmer willingness to share information, which ironically undermines the large-scale data integration necessary for AI models to improve. Machine learning systems get better with more data - but only if farmers trust the platforms enough to contribute their information.

Regulations like GDPR in Europe and CCPA in California impose strict rules about handling personal data, including agricultural data when it involves identifiable farmers. Some regions are developing ag-specific data frameworks that establish farmers' rights to their own information, require explicit consent for data sharing, and mandate transparency about how data gets used.

The ideal model emerging from these debates treats farm data like medical records: generated about you, legally belonging to you, shared with service providers for specific purposes, but never sold or used without explicit permission. Whether this principle becomes universal practice remains an open question, with significant implications for who benefits most from the agricultural data revolution.

Here's a problem nobody anticipated: precision agriculture works so well that farms now have too many tools that don't talk to each other. Your soil moisture sensors use one software platform. Your drone service uploads imagery to a different system. Your variable rate fertilizer controller runs on yet another interface. And your farm management software - the fourth system - can't integrate data from any of them automatically.

This data silo problem isn't just annoying; it actively reduces the value of precision agriculture. The whole point is synthesizing multiple data streams to make better decisions than any single measurement could support. When sensors can't share information seamlessly, farmers either manually transfer data (time-consuming and error-prone) or abandon the integrated approach and make decisions based on incomplete information.

Industry standards are slowly emerging to address interoperability, but adoption remains uneven. Some manufacturers resist open standards because proprietary ecosystems lock in customers. Others embrace integration because it makes their products more valuable as part of a complete precision agriculture stack.

Edge computing devices that process sensor data on-farm before transmitting to the cloud offer one solution, reducing latency and connectivity requirements while maintaining some interoperability. Local processing also addresses privacy concerns by keeping raw data on-farm and only sharing processed insights with external platforms.

Agricultural equipment used to require mechanical knowledge - understanding how tractors and combines worked, recognizing when something sounded wrong, knowing how to fix it. Precision agriculture demands entirely different skills: interpreting data visualizations, troubleshooting software, understanding statistical confidence intervals in AI recommendations, managing cloud platforms.

This creates both challenges and opportunities. Traditional farmers who've spent decades perfecting their craft now face the prospect of becoming students again. Some embrace the new tools enthusiastically. Others resist what feels like an erosion of hard-won expertise, replaced by algorithms they don't fully trust.

Agricultural education programs are scrambling to catch up. Training centers like AGCO's facility offer hands-on courses in precision agriculture technology, achieving 95% job placement rates for graduates who start at average salaries of $55,000 - solid middle-class wages in rural areas where such opportunities have become scarce.

"Farmers with related expertise - agronomic training or technical education - were significantly more likely to adopt precision agriculture, suggesting knowledge barriers may be as important as financial ones."

- Kentucky Small-Scale Farm Study, 2025

The Kentucky study found that farmers with related expertise (agronomic training, technical education) were significantly more likely to adopt precision agriculture, suggesting that knowledge barriers may be as important as financial ones. Extension services, agricultural cooperatives, and equipment dealers increasingly offer training programs, recognizing that education is essential for market growth.

There's also a generational component. Younger farmers who grew up with smartphones and data analytics often find precision agriculture platforms intuitive in ways their parents don't. This creates potential for knowledge transfer in reverse - children teaching parents about technology - though it can also generate family tensions when traditional authority structures get challenged.

Numbers make precision agriculture's environmental case compelling, but the story behind them matters just as much.

Abiotic stressors - water scarcity, nutrient deficiencies, extreme climate events - account for nearly 50% of global crop yield losses. Precision agriculture directly addresses these challenges by matching inputs to actual plant needs rather than applying everything prophylactically.

Take nitrogen fertilizer. Farmers have historically over-applied because the cost of too little (lower yields) outweighs the cost of too much (wasted fertilizer). But "too much" nitrogen doesn't just disappear - it leaches into groundwater, runs off into rivers and lakes causing algal blooms, and converts to nitrous oxide, a greenhouse gas nearly 300 times more potent than CO2.

Precision nitrogen management using soil sensors and AI-driven recommendations cuts application rates by 10-20% while maintaining or improving yields. Scaled globally, that reduction could prevent millions of tons of greenhouse gas emissions and dramatically reduce water pollution from agricultural runoff.

Similar patterns emerge for water use, where precision irrigation based on soil moisture sensors and weather forecasts delivers exactly what plants need, when they need it. The 33% reduction in California almond orchards isn't unusual - many precision irrigation projects report 20-40% water savings.

Pesticide use tells perhaps the most dramatic story. Blanket spraying treats entire fields to control pests that might only infest small areas. AI-powered monitoring that detects infestations early and predicts where they'll spread next enables targeted spot treatment. Some systems report 70-80% reductions in total pesticide use.

Precision agriculture delivers measurable environmental wins: 33% less water use, 10-20% reduction in nitrogen fertilizer, and up to 80% cuts in pesticide application - all while maintaining or improving yields.

These environmental benefits create a virtuous cycle. Less chemical runoff means healthier soil ecosystems, which support beneficial insects and microorganisms, which in turn help control pests and improve nutrient availability. Farms become more resilient even as they become more efficient.

By 2050, humanity will need to feed nearly 10 billion people while confronting climate change that makes farming more difficult through increased droughts, floods, heat waves, and unpredictable weather patterns. Precision agriculture isn't a silver bullet, but it's one of the most promising tools we have.

The global precision agriculture market is projected to reach $11.1 billion by 2025, reflecting massive investment in technologies that promise to increase yields while reducing environmental impact. That combination - more food from less resource-intensive farming - represents exactly what sustainable intensification looks like in practice.

But realizing this potential requires solving the accessibility challenges that currently limit precision agriculture mostly to large commercial farms in wealthy countries. If these technologies remain expensive luxuries, they'll exacerbate existing inequalities between industrial and smallholder agriculture, between developed and developing regions.

Alternative models are emerging. Equipment-sharing cooperatives allow multiple small farms to jointly purchase expensive technology and share usage. Drone service providers offer pay-per-flight crop monitoring, eliminating the need for farmers to buy their own UAVs. Cloud-based AI platforms charge subscription fees rather than requiring massive upfront investment. Mobile apps provide precision agriculture recommendations based on satellite data and weather forecasts, accessible to anyone with a smartphone.

The key insight is that precision agriculture isn't one technology - it's a spectrum of approaches at different price points and complexity levels. A smallholder farmer in Kenya using a mobile app to get weather-based planting recommendations is practicing precision agriculture just as much as an Iowa corn farmer with AI-guided autonomous tractors, even though their tools look completely different.

The technologies reshaping farming today are primitive compared to what's coming. Current systems still require substantial human oversight and decision-making. The next generation will be increasingly autonomous, with AI not just recommending actions but implementing them directly through robotic equipment that plants, monitors, treats, and harvests with minimal human intervention.

Computer vision combined with machine learning is already enabling systems that distinguish individual plants from weeds, allowing precise herbicide application - or mechanical weeding - that targets only unwanted plants. Some experimental systems can even identify specific pest species on leaves and dispatch micro-doses of appropriate pesticide to affected plants only.

Digital twins - virtual models of physical farms that integrate real-time sensor data, weather forecasts, crop growth models, and economic factors - will let farmers simulate different management strategies before implementing them. What happens if I delay harvest by a week to let crops mature? If I apply extra irrigation now versus waiting for next week's predicted rain? If I switch to a different hybrid next season?

Gene editing technologies like CRISPR are being combined with precision agriculture data to develop crops optimized for specific environments and farming practices. Varieties bred for low-input systems can maximize the resource efficiency that precision agriculture enables.

Blockchain-based systems might create transparent supply chains where consumers can verify exactly how their food was produced - which pesticides were used, how much water, what the carbon footprint was - potentially commanding premium prices for producers who can document sustainable practices.

The long-term vision borders on science fiction: farms that are ecosystems carefully orchestrated by AI, where sensors and robots maintain optimal conditions for each plant, beneficial insects and microorganisms handle pest control and nutrient cycling, and human farmers function as managers overseeing autonomous systems rather than manual laborers.

For farmers considering precision agriculture, the path forward isn't "do everything at once" versus "ignore it completely." The research and real-world implementations point to several principles that increase the odds of successful adoption:

Start with the problem, not the technology. What's your biggest pain point? Labor shortages? Water costs? Pest pressure? Input expenses? Choose precision agriculture tools that address your specific challenges rather than buying technology for technology's sake.

Phase the investment. GPS guidance systems, which reduce overlap and improve efficiency with existing equipment, offer an accessible entry point that delivers immediate value. Add yield monitoring next to build data about field variability. Then incorporate variable rate application once you understand where it matters most. This staged approach spreads costs over time and lets you learn incrementally.

Prioritize interoperability. Before committing to platforms and equipment, ask hard questions about data ownership, export capabilities, and compatibility with other systems. Proprietary ecosystems might work beautifully until you want to add tools from different vendors and discover nothing talks to each other.

Invest in education as much as equipment. The fanciest sensor system in the world creates no value if you don't understand its outputs well enough to make different decisions. Training programs, user communities, and ongoing support matter more than most equipment brochures acknowledge.

Connect with early adopters. The Kentucky survey found that social networks and word-of-mouth significantly influence technology adoption decisions. Farmers who've already implemented precision agriculture can provide honest assessments of what worked, what didn't, and what they'd do differently - far more valuable than vendor marketing claims.

Think long-term. Precision agriculture transforms farming gradually rather than overnight. The real benefits compound over multiple seasons as you build data, refine practices, and learn to interpret and trust the systems. Patience and persistence matter more than expecting immediate miracles.

For all the discussion of sensors and algorithms, the most important factor in precision agriculture remains the human one. The best systems amplify rather than replace agricultural expertise - they handle data processing and pattern recognition at scales impossible for humans while leaving judgment and strategy to farmers who understand their land in ways no algorithm can capture.

"The integration of AI and XAI in agricultural forecasting represents a shift from uniform field treatment to zone-specific management."

- Agricultural AI Research Team

That shift still requires human insight about which zones matter, what trade-offs are acceptable, how to balance short-term costs against long-term sustainability.

Robert Fryers, CEO of the insect monitoring company Spotta, describes early days in the field: "When I started, I was surprised by how little investment was going into the technology. I expected all the big players to be busy, but the old way of doing this was still dominant." That's changing, but slowly, as farmers figure out how precision agriculture fits their operations rather than adopting it wholesale because it's trendy.

The most successful implementations seem to be ones where farmers treat AI as a collaborator rather than a replacement - using algorithmic insights to inform decisions while applying contextual knowledge the models lack. A drone might identify apparent nitrogen deficiency in one field section, but the farmer knows that area has different soil types that naturally show lower readings without affecting yield. A sensor network might recommend irrigation, but the farmer knows equipment access is difficult and rain is forecast in three days.

This hybrid approach - high-tech tools combined with hard-won expertise - represents the realistic future of farming. Not autonomous AI that farmers passively monitor, but rather intelligent assistance that makes human decision-making more informed, more timely, and more effective.

The transformation of agriculture through AI and smart sensors isn't a distant possibility or science fiction scenario. It's happening right now on farms across the world, delivering measurable improvements in productivity, profitability, and environmental sustainability. The question isn't whether precision agriculture works - the data clearly shows it does - but how quickly it can scale beyond early adopters and reach the billions of farmers who could benefit.

Economic, infrastructural, educational, and cultural barriers remain substantial, particularly for small and medium-sized operations and in developing regions. But the trajectory is clear: farming is becoming a data-driven profession where algorithms process information at scales impossible for humans, while farmers focus on strategy, judgment, and the subtle contextual knowledge that makes agriculture as much art as science.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Climate change is making farming harder just as population growth demands more food. Water scarcity threatens production in crucial agricultural regions. Soil degradation from decades of intensive practices reduces natural fertility. Precision agriculture offers proven tools to address all these challenges, producing more food while using less water, fewer chemicals, and lower carbon emissions.

The technology has matured. The business case, while still skewed toward larger operations, is increasingly compelling across farm sizes. The environmental benefits are well-documented. What remains is closing the gaps - in infrastructure, education, access, and trust - that prevent precision agriculture from reaching its full potential as a cornerstone of sustainable food production.

For farmers willing to learn new skills and adapt their practices, precision agriculture represents opportunity: to reduce costs, improve yields, demonstrate environmental stewardship, and future-proof operations against climate uncertainty. For society as a whole, it offers a pathway to meet humanity's food needs without destroying the ecosystems that make agriculture possible in the first place.

The revolution is underway. The question now is how quickly we can help it spread.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

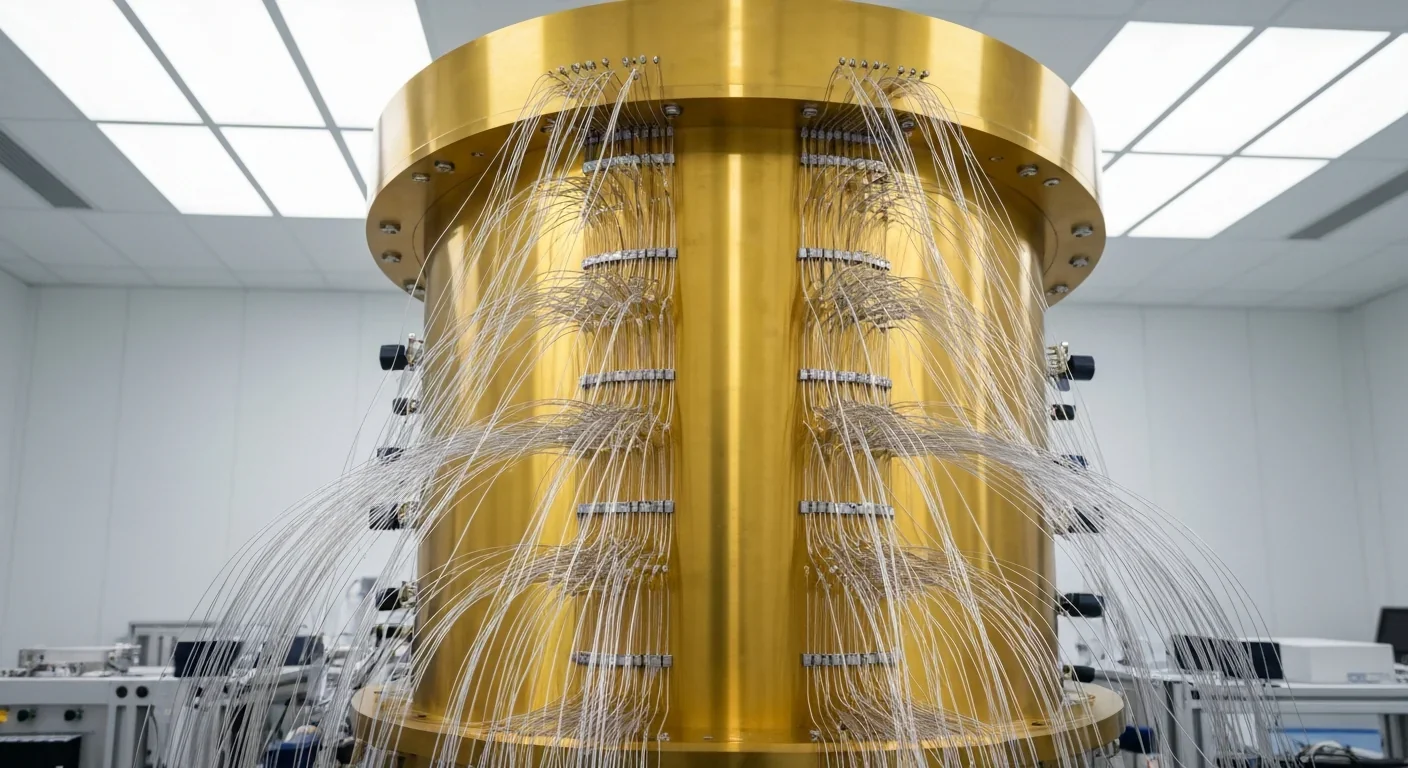

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.