3D-Printed Coral Reefs: Can We Engineer Marine Recovery?

TL;DR: Fast fashion's environmental cost is staggering: each European discards 12kg of clothes yearly while a single t-shirt consumes 2,700 liters of water. The industry generates up to 8% of global emissions and floods oceans with microplastics, but circular business models and policy interventions offer paths toward sustainable transformation.

Every year, the average European buys enough new clothes to fill a large suitcase - 19 kilograms of textiles per person. Within months, around 12 kilograms of those purchases end up in the trash. That's not a wardrobe refresh; that's a disposable culture spinning wildly out of control. The fashion industry has perfected the art of making us feel outdated, convincing millions that last season's jeans aren't just old, they're obsolete. But here's what the industry doesn't advertise: every discarded t-shirt, every unworn dress rotting in a landfill, represents a hidden environmental debt so massive that it threatens water supplies, accelerates climate change, and chokes marine life with microplastics. The clothes on your back aren't just fashion statements anymore, they're environmental confessions.

Making a single cotton t-shirt requires 2,700 liters of fresh water - enough to keep one person hydrated for 2.5 years. That's not a typo. The European Environmental Agency confirms that in 2022, the average EU consumer's textile habit demanded 323 square meters of land, 12 cubic meters of water, and 523 kilograms of raw materials. We're essentially trading ecosystems for outfits.

Cotton cultivation alone accounts for about 2.6% of global water use, and conventional farming practices pile on the damage. Conventional cotton production relies heavily on synthetic pesticides and fertilizers, contaminating soil and waterways while depleting nutrients faster than they can regenerate. Organic cotton offers some relief - it uses 91% less water and eliminates toxic chemicals - but it still represents a tiny fraction of global production.

Beyond raw materials, the dyeing and finishing processes create catastrophic pollution. Textile production is responsible for about 20% of global clean water pollution, primarily from dyeing. Rivers in textile manufacturing hubs run bright blue, red, or whatever color happens to be trending that season. Communities downstream pay the price with contaminated drinking water and devastated aquatic ecosystems.

The fashion industry generates between 2% and 8% of global carbon emissions, depending on how you calculate supply chain impacts. That range might sound vague, but even the conservative estimate puts fashion on par with international aviation and shipping combined. And the trajectory is grim. Despite sustainability pledges, demand continues driving up fast fashion emissions. Brands love to announce eco-friendly collections, but overall production volumes keep climbing.

Polyester, now the dominant fiber in global apparel, has become the elephant in the room. Virgin polyester production hit record levels in 2024, worsening greenhouse gas emissions across the industry. Since polyester is derived from petroleum, every polyester garment locks in fossil fuel dependency. Worse, polyester clothes shed microplastic fibers every time they're washed, creating a pollution problem that persists for centuries.

The industry's transparency on climate action remains shockingly poor. Fashion Revolution's 2025 report found that most major brands still fail to disclose comprehensive emissions data or credible reduction plans. Without transparency, all those sustainability marketing campaigns start looking like greenwashing.

Here's something disturbing: every time you wash synthetic clothing, thousands of microscopic plastic fibers break off and flow down the drain. These microplastic fibers account for 35% of primary microplastics released into oceans, making textile laundering one of the largest sources of marine plastic pollution. Unlike visible plastic bottles or bags, microplastics are nearly impossible to remove once they enter ecosystems.

The scale is mind-boggling. A single load of polyester laundry can release 700,000 microfibers. These particles are so small they pass straight through wastewater treatment plants and accumulate in rivers, oceans, and eventually the food chain. Scientists have found microplastics in seafood, drinking water, and even human blood. We're literally wearing the pollution that's infiltrating our bodies.

Solutions are emerging, though slowly. Cities and states are testing washing machine microplastic filters after global treaty negotiations collapsed. Companies like PlanetCare offer filter systems that capture up to 90% of microfibers before they reach waterways. France has already mandated microfiber filters in all new washing machines by 2025, setting a precedent other nations are watching closely.

Fast fashion operates on a brutal cycle: produce cheap, sell fast, discard faster. The result? Textile waste is reaching tipping point levels across Europe. BCG analysis reveals that current waste management infrastructure can't handle the volume of clothing being thrown away. Only a fraction gets recycled; most ends up incinerated or buried in landfills where synthetic materials can persist for 200+ years.

The problem isn't just volume, it's complexity. Modern garments blend multiple fiber types - cotton-polyester blends, elastane-nylon mixes - making them nearly impossible to recycle with current technology. Zippers, buttons, and decorative elements add more complications. Fashion's hidden cost includes not just production impacts but the impossibility of safely disposing of what's been made.

Some waste doesn't even make it to landfills. Unsold inventory gets incinerated to protect brand value, a practice that destroys usable goods while pumping more carbon into the atmosphere. When pressed, companies claim they're "generating energy" from incineration, but burning textiles releases toxic chemicals and greenhouse gases that far outweigh any energy recovery.

Not all fashion operates this way. A growing number of brands are pioneering circular business models that challenge the take-make-dispose paradigm. Patagonia's Worn Wear program buys back used gear, repairs it, and resells it, keeping products in use for years longer. The company also publishes detailed supply chain information and actively campaigns against overconsumption, sometimes telling customers not to buy unless they truly need it.

Eileen Fisher has built an entire circular system called Renew, collecting old garments from customers, sorting them for resale or redesign, and processing damaged pieces into new fiber. The company has diverted hundreds of thousands of pounds from landfills while proving that circular fashion can work at scale.

Rental platforms represent another shift. Rent the Runway and similar services let consumers access high-quality fashion without ownership, dramatically reducing the number of items manufactured. One dress rented 30 times has a vastly smaller environmental footprint than 30 dresses worn once.

New materials are entering the market too. Companies are developing textiles from mushroom leather, algae-based fibers, and recycled ocean plastic. Innovations in sustainable materials show that fashion doesn't have to mean environmental destruction, though scaling these alternatives remains challenging.

You don't need to wait for industry transformation to reduce your fashion footprint. Start by interrogating your own buying habits. Do you actually need that new shirt, or does advertising just make you feel like you do? The most sustainable garment is the one you already own.

When you do buy, choose quality over quantity. A well-made item that lasts five years beats five cheap items that fall apart in months. Look for natural fibers like organic cotton, linen, or hemp when possible. Check for certifications like GOTS (Global Organic Textile Standard) or Fair Trade, which signal better environmental and labor practices.

Buy secondhand whenever feasible. Thrift stores, consignment shops, and online resale platforms offer huge selections at lower prices while keeping existing clothes in circulation. Vintage fashion often features better construction than modern fast fashion anyway.

Extend the life of what you have. Learn basic repairs like sewing on buttons or patching holes. Wash clothes less frequently and in cold water to reduce microfiber shedding and energy use. When you do wash synthetic fabrics, consider installing a microfiber filter or using a Guppyfriend washing bag that captures shed fibers.

Support brands doing it right. Vote with your wallet for companies that demonstrate transparency, pay living wages, and invest in genuine sustainability rather than greenwashing. Demand accountability through social media and customer feedback.

Consumer action matters, but systemic change requires policy intervention. The European Union is leading with aggressive regulation. New EU laws mandate that textiles must be more durable, repairable, and recyclable. Extended Producer Responsibility schemes will force brands to pay for the waste their products create, incentivizing better design from the start.

The EU's Digital Product Passport will require detailed information about every garment's materials, production location, and environmental impact, making greenwashing much harder. Similar initiatives are emerging globally as governments recognize that voluntary corporate sustainability commitments aren't working.

Banning or taxing virgin polyester production could dramatically shift material choices toward recycled alternatives. Carbon pricing for the full fashion supply chain would force companies to internalize environmental costs currently dumped on society. Worker protection laws addressing the industry's labor exploitation would tackle the social dimension of sustainability.

Some advocates push for even bolder measures: mandatory minimum lifespans for clothing, prohibitions on destroying unsold inventory, or caps on how many collections brands can release annually. These proposals face industry resistance, but the scale of the crisis may leave no alternative.

Fast fashion as we know it is unsustainable in the most literal sense. The model depends on finite resources consumed at accelerating rates, generating waste that accumulates indefinitely. Something has to give, and increasingly, that something is the planet's capacity to absorb the damage.

The transformation won't be simple. Millions of jobs depend on current production systems, particularly in developing countries where garment manufacturing provides crucial employment. Transitioning to sustainable fashion requires supporting workers through economic shifts, not abandoning them.

Technology will play a role. AI-driven design could minimize waste by predicting demand more accurately. Automated recycling systems might finally crack the challenge of separating blended fibers. Biological solutions like enzymes that break down synthetic materials offer promise.

But technology alone won't solve this. The fundamental problem is cultural: we've been conditioned to treat clothing as disposable, to chase trends instead of value, to measure identity through constant consumption. Changing that requires rethinking what fashion means and who it serves.

The clothes you choose to buy, wear, and discard ripple outward in ways that aren't immediately visible but are profoundly real. Cotton fields drained dry. Rivers running toxic colors. Microplastics circulating through marine ecosystems and into the fish on your dinner plate. Landfills swelling with textiles that will outlast multiple human generations.

Fashion will always evolve, but it doesn't have to destroy. Every purchasing decision is a vote for the kind of industry you want to exist. Every garment kept in use instead of discarded is a small act of resistance against a wasteful system. The question isn't whether you can make a difference, it's whether you'll choose to.

The industry's environmental debt is already immense, but it's not yet irreversible. Between smarter policies, better business models, and millions of consumers choosing differently, another future is possible: one where fashion enhances life without consuming the planet. That transformation starts with understanding the true cost of fast fashion - and refusing to pay it.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

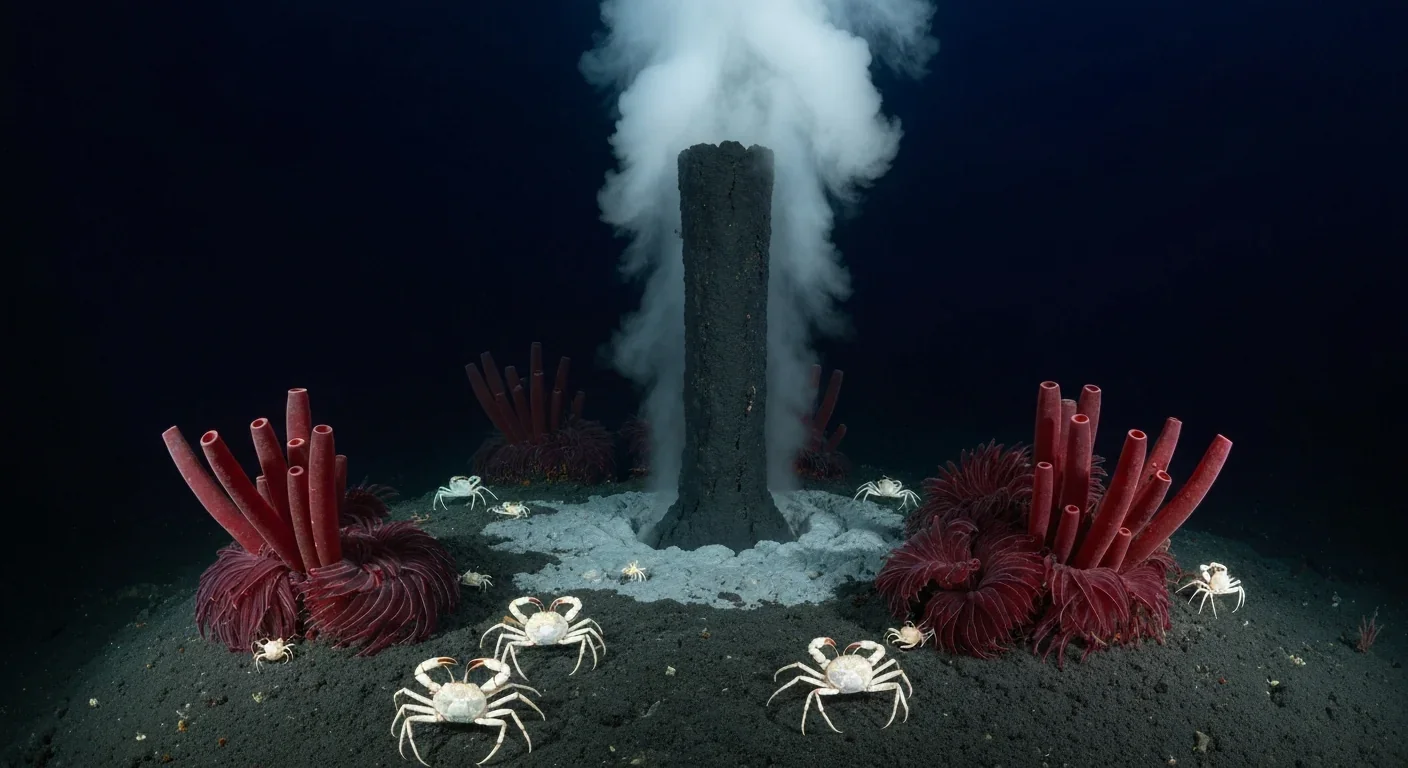

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

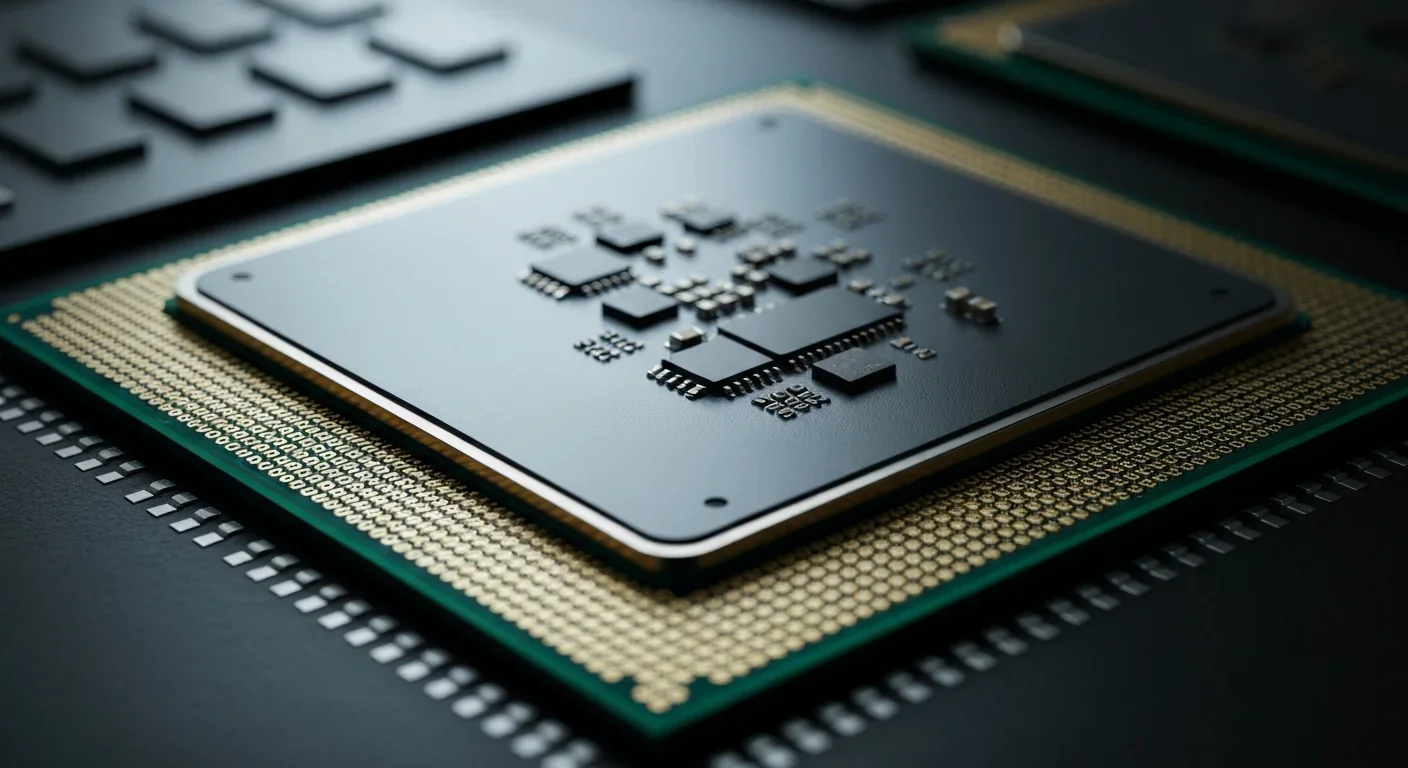

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.