AI Cameras Save Sea Turtles in Fishing Nets

TL;DR: Farmers and conservationists are converting marginal cropland back to native grasslands, delivering measurable benefits: prairie ecosystems sequester 4.5x more carbon than turf grass, reduce nitrogen runoff by 95 percent, and restore wildlife habitat. Federal programs like CRP provide financial incentives including rental payments and cost-share assistance, making restoration economically viable despite challenges around policy uncertainty and cultural resistance.

Across the American heartland, a quiet revolution is taking root. Fields that once grew corn and soybeans are being transformed into seas of tallgrass prairie, complete with native wildflowers, deep-rooted grasses, and the hum of pollinators. This isn't abandonment; it's restoration. Landowners are deliberately converting marginal cropland back to native grasslands, motivated by a mix of environmental benefits, financial incentives, and the recognition that not all land should produce annual crops.

The movement represents more than nostalgia for lost ecosystems. It's a pragmatic response to climate change, biodiversity loss, and the limits of industrial agriculture. As farmers grapple with degraded soils, water pollution, and unpredictable weather, grassland restoration offers a viable alternative for lands that were never suited to the plow in the first place.

Native grasslands aren't just pretty. They're ecological powerhouses that deliver benefits conventional agriculture can't match. Prairie ecosystems can sequester up to 1.8 metric tons of carbon per hectare annually, compared to just 0.4 metric tons for traditional turf grass. That difference stems from what you can't see: root systems that plunge ten feet or more into the soil, storing carbon where it belongs.

The math gets more impressive at scale. The Conservation Reserve Program has prevented more than 9 billion tons of soil from eroding since its inception, protecting topsoil that took millennia to form. Water quality improves dramatically too. When cropland converts to grassland, nitrogen runoff drops by 95 percent and phosphorus by 86 percent, according to research from the Food and Agricultural Policy Research Institute.

Native prairie ecosystems can sequester up to 1.8 metric tons of carbon per hectare annually, while traditional turf grass captures only 0.4 metric tons - a 4.5x difference that happens underground through deep root systems.

For wildlife, restored grasslands function as lifelines. Duck populations in the Prairie Pothole Region increased 30 percent since 1992, coinciding with major conservation efforts. Pollinators, ground-nesting birds, and dozens of other species depend on these habitats. CRP lands protect more than 170,000 stream miles with vegetation that filters runoff and creates cleaner water downstream.

Converting cropland to prairie sounds simple: stop farming, plant native seeds, wait. The reality involves more nuance. Successful restoration requires matching plant species to local soil and climate conditions, controlling invasive species, and managing the land through prescribed burns or grazing once vegetation establishes.

The timeline stretches longer than most people expect. CRP contracts typically run 10 to 15 years, reflecting how long native plant communities need to establish and mature. First-year plantings look sparse and weedy. By year three, native grasses dominate. By year five, the ecosystem starts resembling what was lost a century ago.

Site preparation matters enormously. Some landowners hire ecological restoration companies to handle seed selection, site prep, and planting. Others tackle the work themselves, learning as they go. Either way, establishing native vegetation costs money upfront: site preparation, high-quality native seed, and labor.

Restoration techniques vary by region and goals. In the tallgrass prairie region, landowners might plant diverse mixes with 40 or more species. In semi-arid regions, simpler grass-dominated mixes work better. Some projects emphasize carbon sequestration, others prioritize wildlife habitat or water quality.

The ecological payoff compounds over time. Diverse native plantings develop complex root systems that store carbon and improve soil structure. Soil organic matter increases. Water infiltration improves. The land becomes more resilient to drought and extreme weather.

Money drives land use decisions. For grassland restoration to scale, the economics need to work. Federal conservation programs have been the primary mechanism making restoration financially viable for private landowners.

The Conservation Reserve Program offers annual rental payments to landowners who convert environmentally sensitive cropland to conservation cover. Payments vary by county and soil type, but rental rates track local land values. Additionally, the program provides cost-share assistance of up to 50 percent for establishing vegetation, with additional incentives available for certain practices.

"The CRP's blend of cost-share and rental payments offers a financially viable model that could be replicated or adapted for prairie restoration, potentially lowering initial investment barriers for landowners."

- Conservation Reserve Program Analysis

Annual CRP payments are capped at $50,000 per person or legal entity per fiscal year. For many farmers operating on tight margins, that guaranteed income beats gambling on commodity prices for marginal land that produces meager yields anyway.

State programs add another layer. South Dakota recently launched grants helping landowners restore grasslands on marginal cropland. Similar initiatives exist across the Great Plains and Midwest, each tailored to regional priorities and budgets.

The emerging carbon credit market represents a new financial avenue. Companies like AgriCapture connect landowners with buyers seeking carbon offsets. Grassland restoration generates verified carbon credits that landowners can sell, potentially creating long-term revenue streams beyond government programs.

Yet financial barriers remain significant. Low CRP application acceptance rates and shrinking acreage caps have frustrated landowners wanting to enroll. When budget constraints tighten, conservation programs face cuts. Without reliable financial support, many landowners can't justify the transition.

Abstract benefits become real when you see restored prairies thriving. In Iowa, habitat headquarters demonstrate prairie restoration techniques on working lands, showing farmers what's possible. Native plantings attract wildlife, improve water quality, and provide educational opportunities.

The Western Sustainability Exchange works with ranchers across Montana to restore degraded grasslands while maintaining livestock operations. Their approach integrates conservation with ranching economics, proving restoration doesn't require abandoning agricultural livelihoods.

Minnesota's Prairie Restorations showcases success stories where landowners transformed degraded sites into thriving native ecosystems. These projects span small backyard prairies to hundreds of acres, demonstrating scalability. Each restoration tells a story of patience, persistence, and ecological recovery.

CRP contracts typically run 10 to 15 years because native plant communities need that long to establish and mature. First-year plantings look sparse, but by year five, the ecosystem resembles what was lost a century ago.

In Texas, the Native Prairies Association of Texas advances restoration across the state's diverse ecological regions. Their work preserves remnant prairies while expanding restored habitat, connecting fragmented landscapes crucial for wildlife movement.

Recent partnerships expand restoration reach. Audubon Conservation Ranching partnered with Kateri to advance regenerative ranching and grassland conservation, creating market incentives for landowners managing grasslands sustainably.

Converting cropland to grassland faces obstacles beyond finances. Cultural attitudes present perhaps the biggest barrier. For generations, productive farmland meant row crops. Prairie was what you plowed under, not what you restored. Changing that mindset takes time.

Knowledge gaps create practical challenges. Most landowners lack experience with native plant establishment and long-term prairie management. Prescribed burning, once routine on the plains, now requires permits, training, and equipment many landowners don't have.

Invasive species complicate restoration efforts. Non-native plants like smooth brome and reed canary grass aggressively colonize disturbed sites, outcompeting natives. Controlling invasives requires years of monitoring and management, adding costs and labor.

Land tenure patterns don't always favor long-term restoration. Rental farmland changes hands frequently. CRP's 10-to-15-year contracts require commitment landlords and renters may be unwilling to make. Even landowners receptive to restoration worry about decisions that bind future generations.

Policy uncertainty undermines confidence. Federal farm bills get renegotiated every five years. Acreage caps fluctuate with political winds. Landowners considering restoration can't predict whether programs supporting them today will exist tomorrow.

Scale poses another challenge. Individual restored parcels, however ecological sound, can't support viable wildlife populations if isolated in seas of row crops. Landscape-level restoration requires coordinating multiple landowners, a process complicated by differing priorities and timelines.

Grassland restoration intersects with climate change mitigation in profound ways. Prairies sequester carbon both above and below ground, with native prairie plants growing deeper and more extensive root systems than agricultural crops. Those roots pump carbon into soil where it can remain for decades or centuries.

The climate benefits extend beyond sequestration. Perennial grasslands reduce greenhouse gas emissions compared to annual cropping systems that require tillage, fertilizer production, and diesel-burning machinery. Converting cropland on organic-rich or peat soils to grassland prevents carbon releases from disturbed earth.

"Deep root systems of prairie plants dramatically enhance long-term soil carbon storage, implying that restoring native grasslands can yield similar deep-rooted benefits for carbon sequestration beyond just above-ground biomass."

- Native Landscape Research

Restored grasslands also build climate resilience. Deep-rooted prairies withstand drought better than annual crops, their roots accessing moisture conventional plants can't reach. During heavy rains, prairie vegetation slows runoff and improves water infiltration, reducing flooding downstream.

Research increasingly documents these benefits. A systematic review examining cropland-to-grassland conversion found consistent greenhouse gas emission reductions, particularly on peat and organic-rich soils. The climate case for restoration grows stronger as data accumulates.

Carbon markets recognize grassland restoration's climate value. Grassland carbon credits create financial mechanisms rewarding landowners for ecosystem services. While markets remain nascent and prices volatile, they signal growing recognition that natural climate solutions deserve investment.

Federal policy shapes grassland restoration possibilities. The Conservation Reserve Program, established in the 1985 Farm Bill, remains the primary vehicle for cropland conversion. Over decades, CRP has enrolled millions of acres, though acreage has fluctuated with changing political priorities.

Beyond CRP, the Environmental Quality Incentives Program and Conservation Stewardship Program offer additional pathways. EQIP provides financial assistance for conservation practices on working lands. CSP rewards landowners already managing resources sustainably. Together, these programs create a conservation toolkit supporting various restoration approaches.

State-level initiatives complement federal programs. Iowa's wetland restoration efforts integrate grassland buffers protecting water quality. State wildlife agencies provide technical and financial assistance for habitat restoration, recognizing connections between grasslands and game species.

The Conservation Reserve Program has prevented more than 9 billion tons of soil from eroding since its inception, protecting topsoil that took millennia to form.

Nonprofit organizations fill gaps government programs miss. Groups like the Missouri Prairie Foundation protect and restore prairie remnants, providing landowner education and ecological expertise. The IUCN's grassland restoration initiatives work globally, recognizing grasslands as vital ecosystems deserving conservation attention.

Policy debates continue around program funding, acreage caps, and priorities. Conservation advocates push for expanded CRP enrollment, arguing demand exceeds available acres. Budget hawks question costs. The tension between agricultural production and conservation plays out in every farm bill negotiation.

Not all farmland deserves farming. Marginal agricultural land produces poor yields, erodes easily, or requires excessive inputs for minimal returns. These are prime candidates for grassland restoration.

Identifying marginal land requires understanding soil quality, topography, climate, and economics. Steep slopes erode badly under cultivation. Sandy or shallow soils lack the structure supporting productive crops. Drought-prone regions can't reliably produce moisture-demanding corn or soybeans.

The 2023 research on agricultural abandonment and recultivation examined future environmental benefits of converting marginal cropland. Results suggest strategic land use changes could deliver substantial ecological gains without significantly impacting food production.

For farmers, marginal land presents frustrating economics. Input costs match or exceed those on productive ground, but yields lag far behind. Converting marginal acres to conservation cover through programs like CRP can generate more reliable income than gambling on commodity markets.

The agricultural economics shift further when you factor erosion and degradation. Farming marginal land often accelerates soil loss, diminishing future productivity. Restoration halts that decline and begins rebuilding soil resources, an investment in long-term land value.

Climate volatility makes marginal land even more marginal. As weather extremes intensify, lands barely profitable in average years lose money in droughts or floods. Grassland restoration offers stability unpredictable crop yields can't match.

Grassland restoration momentum continues building. Climate change awareness drives interest in nature-based solutions. Carbon markets mature. Scientific evidence documenting restoration benefits accumulates. Each factor pushes the movement forward.

Technology plays an emerging role. Soil data and analysis tools help identify restoration opportunities and track outcomes. Remote sensing monitors vegetation establishment and carbon sequestration. Apps connect landowners with technical assistance and program information.

The restoration community grows more sophisticated. Early efforts sometimes used inappropriate seed mixes or neglected post-planting management. Today's practitioners benefit from decades of accumulated experience, better seed sources, and refined techniques.

Younger landowners show greater receptivity to conservation. Having grown up with climate change and biodiversity loss as defining issues, they approach land management differently than previous generations. That shift in values will influence millions of acres as generational land transitions occur.

Policy evolution remains uncertain but crucial. Conservation programs' future funding and structure will determine restoration's pace and scale. Political leadership matters. So does sustained advocacy from conservation organizations keeping grassland issues visible.

International momentum helps too. The UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration elevates grassland conservation globally, recognizing these ecosystems face threats and deserve protection worldwide. Sharing knowledge across borders accelerates learning and innovation.

The prairie comeback won't happen overnight. Restoration proceeds acre by acre, landowner by landowner. But each converted field demonstrates what's possible when ecological knowledge, financial incentives, and landowner commitment align. The grasslands lost over two centuries won't fully return, but bringing back even a fraction delivers benefits worth pursuing.

For landowners considering restoration, resources abound. Government programs provide financial support. Nonprofits offer expertise. Restoration companies handle technical details. The path from cropland to prairie is well-worn now, easier to follow with each passing year.

The question isn't whether grassland restoration makes sense. Science, economics, and ecology answer that affirmatively. The question is whether we'll restore enough fast enough to matter. Every acre helps, but the challenge is large. Prairies once covered hundreds of millions of acres across North America. Less than four percent of tallgrass prairie remains. Closing that gap requires sustained effort, resources, and commitment.

What happens when farmers and conservationists work together? Degraded land becomes vibrant habitat. Carbon moves from atmosphere to soil. Water quality improves. Wildlife populations rebound. The landscape remembers what it was and begins becoming that again. Not exactly as before - history doesn't replay - but close enough to matter, alive enough to thrive, diverse enough to endure.

That future is being planted now, in fields scattered across the heartland. Seeds germinating, roots growing downward, ecosystems reassembling. The prairie comeback is happening. The question is how far it goes.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

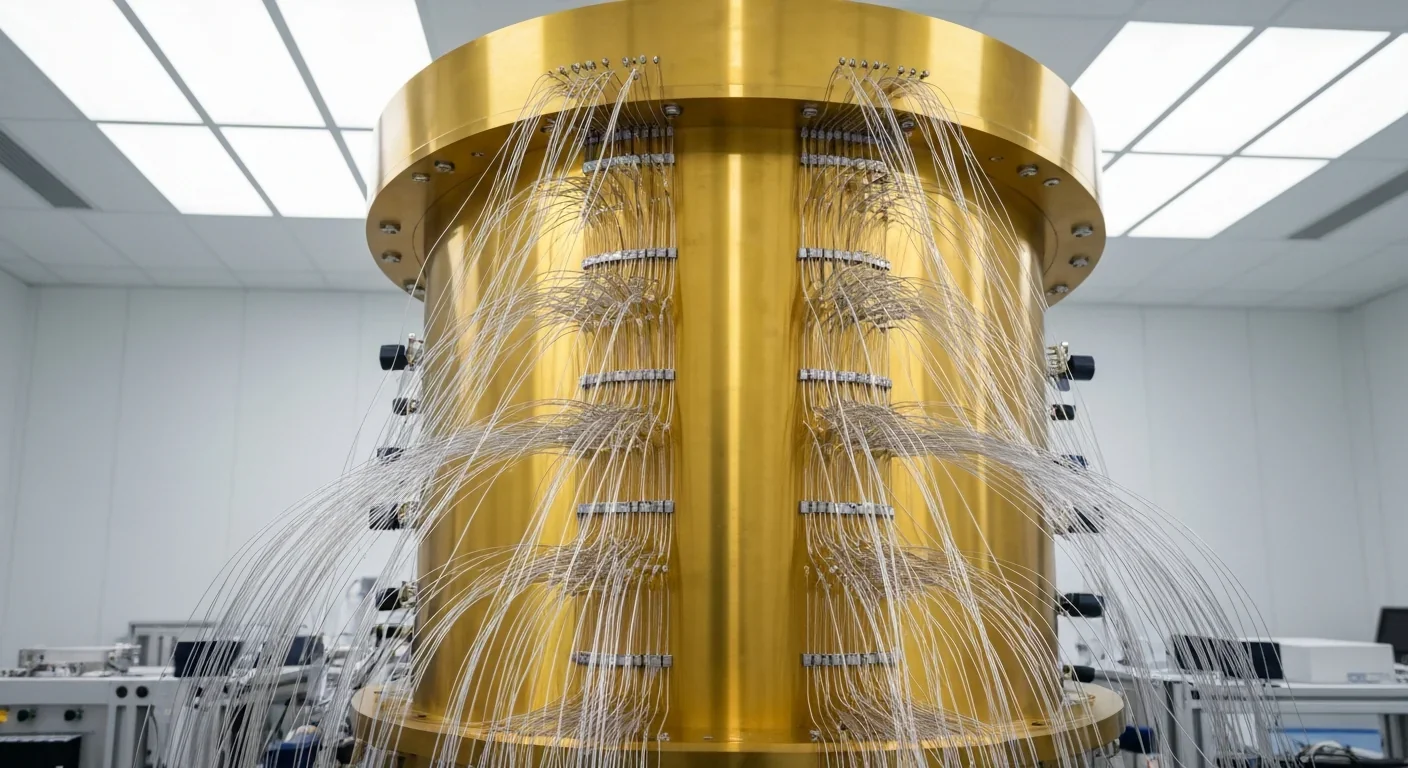

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.