AI Cameras Save Sea Turtles in Fishing Nets

TL;DR: Product-as-service models are replacing ownership with access across industries from fashion to industrial equipment. By retaining product ownership, companies profit from durability rather than obsolescence, enabling circular economy principles. While challenges include consumer psychology and operational complexity, the shift promises to decouple prosperity from material accumulation.

In the next five years, more people will subscribe to their wardrobes than own them outright. They'll lease lighting, rent furniture, and pay per kilometer driven rather than buying tires. This isn't speculation - it's already happening across industries from fashion to heavy machinery, and the shift promises to fundamentally alter humanity's relationship with material goods. Product-as-service (PaaS) models are quietly dismantling the ownership paradigm that has defined consumer culture since the Industrial Revolution, replacing it with something that looks suspiciously like what economists call a circular economy.

The concept sounds simple enough: instead of selling you a product, companies provide the service that product delivers. Philips doesn't sell you light bulbs - they sell you illumination. Michelin doesn't sell tires - they sell kilometers traveled. Fashion companies like Rent the Runway don't sell dresses - they sell access to a rotating wardrobe that adapts to your needs without cluttering your closet.

But scratch beneath the surface and you'll find this represents something far more profound than clever marketing. When companies retain ownership of their products, their economic incentives flip. Planned obsolescence becomes self-sabotage. Durability shifts from cost center to profit driver. Repair infrastructure transforms from grudging obligation to competitive advantage.

Philips discovered this when they pioneered lighting-as-a-service, charging customers for illumination hours rather than bulb sales. The company claims up to 80% energy savings compared to conventional bulbs - not from sudden technological breakthroughs, but because when Philips owns the bulbs, they have every reason to make them last longer and burn less electricity. The longer a bulb survives, the more profit it generates.

When companies retain ownership of products, their economic incentives flip entirely: planned obsolescence becomes self-sabotage, and durability becomes a profit driver rather than a cost center.

This flipped incentive structure creates the foundation for circular design principles that sound great in sustainability reports but rarely materialize in practice. When you sell a product, you profit from its obsolescence. When you service a product, you profit from its longevity.

Consider Michelin's tire-as-service model, where fleet operators pay per kilometer rather than buying tires outright. Michelin now has skin in the game - literally. They profit by designing tires that last longer, can be retreaded multiple times, and whose materials they can recover and reuse. The circular economy principles that sound aspirational in traditional business suddenly become financially imperative.

Fashion for Good's research on circular business models reveals how dramatically this changes product design. When clothing rental companies like Nuuly own their inventory, they design for durability and repairability because each garment needs to survive dozens of rental cycles. The average woman's closet dumps 82 pounds of clothing into landfills annually - a problem that evaporates when business models reward longevity over consumption volume.

The EPA's electronics certification programs show similar patterns emerging in tech. Their R2 and e-Stewards standards create frameworks for responsible electronics management, but product-as-service models provide the economic motivation to actually implement them. When manufacturers lease rather than sell devices, they control the entire lifecycle - and capture value from extended product lifespans and material recovery.

Fashion has become the laboratory for testing how consumers respond to access over ownership. The industry generates massive waste - that 82 pounds per closet isn't an outlier - and fast fashion business models have accelerated consumption to absurd levels. Product-as-service promises an exit ramp.

Fashion for Good's analysis of circular models across market segments reveals both promise and challenges. Rental and subscription models show different viability across Value, Mid-Market, Premium, and Luxury segments. Premium and Luxury see stronger adoption because customers already think of fashion as temporary - they want variety and aren't emotionally attached to owning specific pieces.

But consumer psychology proves trickier than expected. Research on consumer perception reveals significant barriers tied to psychological ownership, perceived value, and ingrained routines. People who grew up buying clothing struggle to reframe their relationship with wardrobes, even when rental makes economic and environmental sense.

Still, the numbers show momentum. Companies like Nuuly report handling cleaning and maintenance - eliminating the hassle of dry cleaning while ensuring garments survive multiple rental cycles. Platform models like By Rotation create peer-to-peer rental networks where people monetize their own closets, spreading the ownership-to-service mentality virally through social networks.

"82 pounds of clothing from the average woman's closet end up in landfill each year - a problem that evaporates when business models reward longevity over consumption volume."

- Rent the Runway Environmental Impact Study

While fashion experiments with consumer psychology, industrial sectors are quietly proving the economics work at massive scale. BNP Paribas Leasing Solutions advanced €16.3 billion in asset finance in 2024, managing a €40.4 billion leased asset portfolio. They're not doing this for sustainability optics - the economics are compelling.

Michelin's tire service expansion shows both the potential and pitfalls. Their local-to-local manufacturing strategy combined with service delivery creates complex logistics, and early profitability lagged expectations. But by 2025, the model found its footing - Michelin's first half financials recorded €1.45 billion in operating income with an 11.3% margin.

What changed? Michelin figured out the operational transformation required. You can't just slap "as-a-service" onto a product business model. The organizational changes involve restructuring sales teams, developing new performance monitoring systems, and building reverse logistics infrastructure to recover and refurbish products.

The SYSTEMIQ consortium's work on "Everything as a Service" documents how these transformations align with EU policy frameworks - specifically the Green Deal and Circular Economy Action Plan. Policy support matters because PaaS models require long-term thinking that quarterly earnings pressures often discourage.

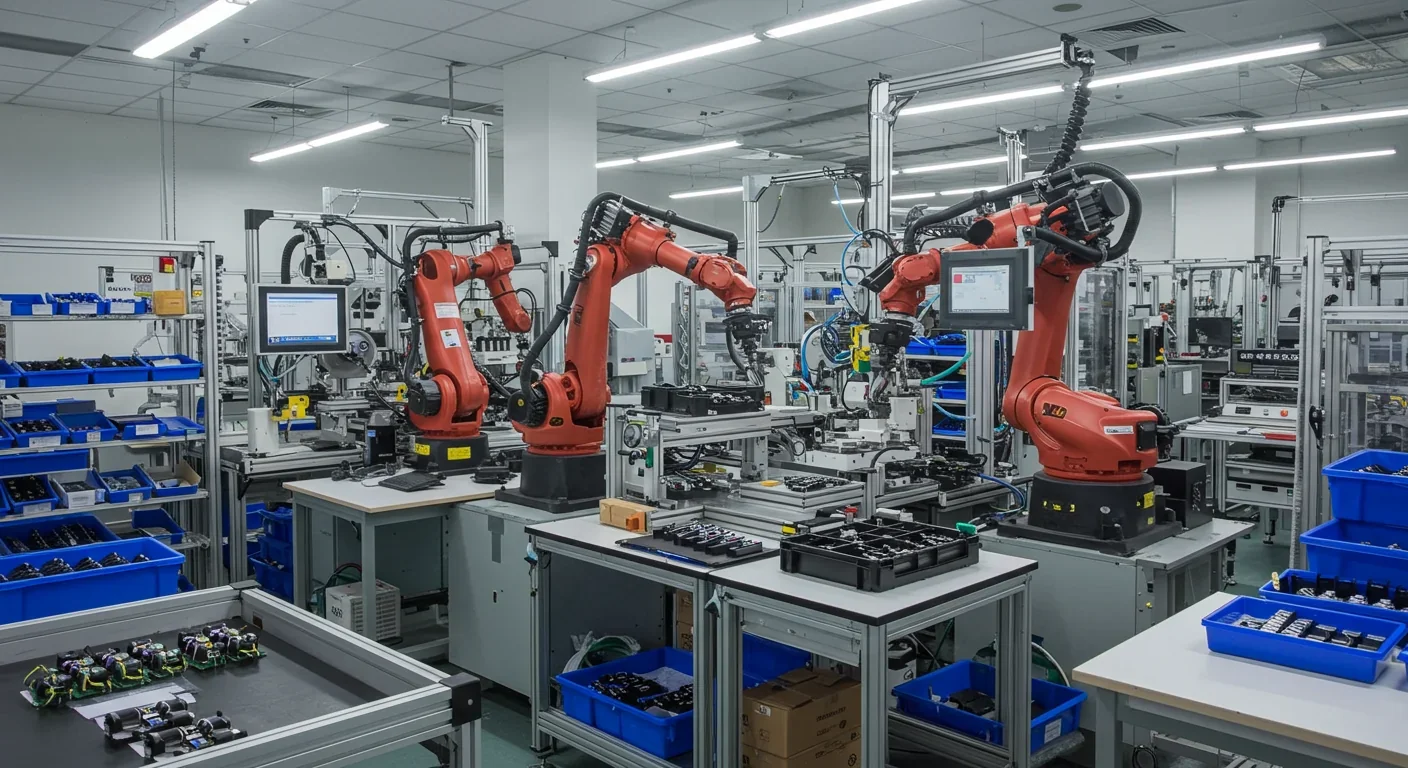

None of this works without technology infrastructure that barely existed a decade ago. IoT sensors embedded in products provide real-time performance data. Cloud platforms manage complex subscription relationships. Digital twins simulate product lifecycles before physical deployment. Blockchain enables transparency in material provenance and recycling.

Digital device passports and blockchain transparency increasingly enhance consumer trust in electronics-as-service models. When you lease a laptop, you want assurance about its maintenance history, security updates, and component origins. Technologies that were theoretical five years ago now enable business models that couldn't exist otherwise.

Platform companies like Rheaply demonstrate how digitizing asset inventories impacts reuse rates. Their asset management systems help organizations track, share, and redeploy equipment rather than letting it gather dust or go to landfills. The total cost of ownership becomes visible and manageable in ways impossible with spreadsheet-based systems.

A simulation of fashion retail challenges shows the complexity of optimizing service models. Researchers modeled a 7-day rental cycle where an average of 56 plastic totes (560 items) were collected daily, peaking at 105 totes (1,050 items) on day 25. The operational metrics - FTE per store, average tote load, truck capacity utilization - make or break profitability. Technology that optimizes these logistics determines whether circular business models succeed or drown in complexity.

IoT sensors, cloud platforms, digital twins, and blockchain technologies that were theoretical five years ago now enable product-as-service business models that couldn't have existed otherwise.

Government policy increasingly recognizes that product-as-service models deliver environmental benefits traditional regulations struggle to achieve. Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) policies make manufacturers responsible for product end-of-life, creating incentives to design for durability and recovery.

Right-to-repair legislation pushes manufacturers toward designs that support longevity. When customers can repair products, planned obsolescence becomes less viable. When manufacturers retain ownership through service models, they benefit from repairability rather than fighting against it.

The EU's Circular Economy Action Plan explicitly promotes "Everything as a Service" models as tools for achieving sustainability targets. This policy support matters because PaaS models often require regulatory clarity around liability, data ownership, and cross-border operations.

Extended Producer Responsibility frameworks in Europe show how policy can accelerate adoption. When producers bear responsibility for post-consumer waste, service models that retain product ownership suddenly look financially attractive. EPR requirements in cross-border e-commerce create complexity, but also level playing fields between ownership and service business models.

Producer Responsibility Organizations (PROs) emerge as mediators between producers and consumers, managing collection and recycling systems that make circular models viable. The state-run EPR models being implemented globally will determine whether product-as-service businesses can scale or remain niche alternatives.

The financial case for PaaS depends on your perspective. For consumers, the equation shifts from high upfront costs to predictable ongoing expenses. For businesses, it trades manufacturing margins for recurring service revenue - a transformation that terrifies CFOs trained in product economics.

BNP Paribas's research suggests financing structures designed to reduce upfront costs for manufacturers prove critical for adoption. Cloud versus on-premises software comparisons show how service models can lower total cost of ownership while providing vendors with more stable revenue streams.

But profitability remains elusive for many early movers. Michelin's initial struggles illustrate how operational transformation lags strategic vision. Fashion rental models show varying attractiveness across market segments, with luxury performing better than value segments where margins are razor-thin.

The challenge: service models require upfront investment in durable, repairable products while revenue accrues slowly over time. Traditional businesses optimize for opposite priorities - minimizing production costs while maximizing sales volume. Companies attempting the transition often discover they're simultaneously running two incompatible business models.

Economic viability means nothing if consumers reject the premise. Research reveals complex psychological barriers tied to ownership identity, control, and trust.

Studies on product adoption barriers identify six common obstacles: lack of awareness, perceived complexity, insufficient value demonstration, poor user experience, inadequate support, and cultural resistance. Product-as-service models trigger nearly all of them simultaneously.

Sector-specific research shows varying barrier weights across mobility, clothing, and tools. Clothing rental faces high psychological ownership barriers - people form emotional attachments to wardrobes. Mobility services face lower barriers - cars are expensive hassles many would happily outsource. Tool sharing faces trust and availability concerns - what if everyone needs the drill simultaneously?

Breaking these barriers requires what researchers call "routine-breaking interventions." The pandemic provided one - suddenly traditional consumption patterns were disrupted, creating openings for alternative models. Climate anxiety provides another - younger demographics increasingly reject ownership-based consumerism for environmental reasons.

Brand perception shifts matter too. Fashion companies successfully reframe rental as sophistication rather than deprivation - access to constantly refreshed wardrobes signals style savvy, not economic constraint. This reframing proves harder in categories where ownership signals status.

"Product-as-service models trigger nearly all adoption barriers simultaneously: lack of awareness, perceived complexity, insufficient value demonstration, poor user experience, inadequate support, and cultural resistance."

- Consumer Psychology Research, Frontiers in Environmental Science

The shift to service models demands fundamental changes in how products are designed, manufactured, and distributed. Philips's transformation from products to platforms illustrates the organizational upheaval involved.

Manufacturers must balance higher upfront costs for durable, repair-ready designs against price competition from low-cost alternatives. When your competitors sell disposable products cheaply, your durable service-model products look expensive - even if lifetime costs are lower.

Additive manufacturing creates possibilities for mass-scale production while maintaining circularity. Philips's 3D printing of custom lighting fixtures demonstrates how digital manufacturing can support personalized service models without sacrificing efficiency.

Loop Industries developed polymer recycling technology converting plastic waste into high-quality raw materials, but technology alone doesn't create circular systems. Business models that capture value from recovered materials do.

Supply chains require complete reconfiguration. Traditional manufacturers optimize for unidirectional flow - raw materials to products to consumers to landfills. Service models require circular flows - products to consumers and back to manufacturers repeatedly. The reverse logistics infrastructure for product recovery, refurbishment, and redeployment represents massive capital investment.

Advocates tout impressive environmental statistics. Philips claims 80% energy savings through lighting-as-service. Fashion rental prevents those 82 pounds per person from reaching landfills. Electronics service models enable component reuse and responsible recycling.

But environmental benefits aren't automatic. Increased transportation for product recovery can offset manufacturing efficiency gains. Cleaning and maintenance for reusable products consume energy and water. Poorly designed service systems might generate more environmental impact than ownership models.

The EPA's electronics initiatives highlight responsible management frameworks, but implementation quality varies wildly. Certification programs like R2 and e-Stewards are "generally well implemented" with identified improvement areas - bureaucrat-speak for "better than nothing but far from perfect."

UN Environment Programme data on global e-waste volumes shows formal recycling rates remain stubbornly low despite decades of effort. Product-as-service models promise improvement by keeping manufacturers connected to product end-of-life, but scaling these models proves challenging.

Circular economy examples across industries show environmental benefits correlate with business model maturity. Early-stage implementations often struggle with efficiency, while established programs demonstrate significant waste reduction and resource conservation.

Underneath the business models and environmental metrics lies a profound cultural question: Can humanity separate wellbeing from accumulation?

For most of modern history, prosperity meant owning things. More things signaled more success. Closets overflowed, garages filled with rarely-used tools, attics stored forgotten purchases. The lifestyle of abundance was measured in possessions.

Product-as-service models propose an alternative: prosperity as access rather than accumulation. Your quality of life improves not from owning more stuff but from having what you need when you need it - and nothing else cluttering your space or attention.

This cultural reframe resonates differently across demographics. Younger generations increasingly embrace experiential consumption over material accumulation. Minimalism movements reject ownership-as-status. Environmental consciousness makes excess consumption feel irresponsible.

But older generations who lived through scarcity often find service models psychologically threatening. Ownership provides security - knowing you have something regardless of economic disruption. Subscription models introduce dependency and vulnerability.

The fashion sector research shows these generational divides clearly. Luxury rental thrives among millennials and Gen Z who view fashion as performance and self-expression rather than property. Value segment rental struggles because consumers in that category often prioritize ownership security over variety.

Product-as-service models propose a radical cultural reframe: prosperity as access rather than accumulation, having what you need when you need it rather than owning everything you might someday use.

Service models risk creating new forms of inequality. In a subscription economy, losing access to essential services - transportation, lighting, tools - becomes a mechanism of social exclusion.

What happens when algorithmic credit scoring determines who can access product-as-service offerings? Traditional ownership, for all its environmental costs, provides a form of economic resilience. You might not have much, but what you own stays yours even if your financial situation deteriorates.

Service models also risk entrenching digital divides. Internet connectivity and digital literacy become prerequisites for accessing basic goods. Rural communities without reliable infrastructure get excluded. Elderly populations uncomfortable with apps and subscriptions find themselves shut out of systems designed for digital natives.

Developing economies face different trade-offs. Product-as-service models might leapfrog wasteful ownership paradigms - but only if infrastructure supports it. Without reliable logistics, maintenance networks, and reverse supply chains, service models remain urban luxuries.

The cross-border EPR requirements highlight how global trade adds complexity. Products crossing borders multiple times during service lifecycles encounter regulatory fragmentation that makes circular models prohibitively expensive.

There's an uncomfortable truth lurking in product-as-service enthusiasm: these models concentrate power with corporations in unprecedented ways.

When you own something, you control it - modify it, repair it, sell it, destroy it. Service models transfer those rights to providers. You become dependent on their continued operation, pricing decisions, and willingness to service your account.

Right-to-repair advocates recognize this tension. They fight for ownership rights while acknowledging service models' environmental benefits. The solution might involve regulatory frameworks ensuring service providers can't abuse their control - but writing those regulations proves politically fraught.

Data ownership represents another power concentration. IoT-enabled products in service models generate continuous data streams about usage patterns, behaviors, and preferences. Who owns that data? Who can monetize it? Traditional ownership provides some data privacy through physical control; service models eliminate that protection.

The consolidation risk is real. If product-as-service becomes dominant, industries could concentrate around a few large platform providers with massive advantages in logistics, data, and capital. The outcome might be environmentally better but economically less competitive and democratically concerning.

So where does this leave us? Standing at an inflection point between ownership and access, between linear and circular, between accumulation and experience.

Product-as-service models aren't a panacea. They introduce new complexities, risks, and trade-offs. But they also represent one of few viable pathways toward decoupling human prosperity from resource extraction and waste generation.

The transition won't happen uniformly. Different sectors will adopt at different rates based on economics, psychology, and infrastructure readiness. Fashion and electronics lead because products are expensive, frequently replaced, and logistically manageable. Furniture and appliances follow because durability improvements deliver clear value. Fast-moving consumer goods face higher barriers because individual item values don't justify reverse logistics costs.

Policy will shape adoption speed. Governments supporting circular economy principles through EPR frameworks, right-to-repair laws, and service-model-friendly regulations can accelerate transition. Those maintaining regulatory structures designed for ownership economies will slow it.

Corporate strategy will evolve through painful trial and error. Early movers like Michelin demonstrate both the long-term potential and near-term profitability challenges. Late movers might learn from others' mistakes - or find themselves disrupted by competitors who mastered service model economics first.

Consumer acceptance will determine ultimate viability. No matter how elegant the business model or how compelling the environmental case, service models fail if people reject them. The psychological shift from ownership to access represents a generation-long cultural evolution, not a quarterly business initiative.

Imagine arriving in 2035. You still have clothing, electronics, furniture, and transportation - but you own almost none of it. Your wardrobe updates monthly through a fashion service tailored to your style and upcoming events. Your living room furniture adapts as your life changes - cribs when kids arrive, office furniture when you work from home, senior-friendly designs as parents age.

Your lighting automatically optimizes for circadian rhythms and seasonal changes. Your transportation shifts seamlessly between autonomous rides, e-bikes, and shared electric vehicles depending on distance and weather. Tools appear when needed for specific projects, then disappear back into shared networks.

This isn't utopia - there are costs. You're dependent on service providers remaining financially stable. You're trusting algorithms to anticipate needs and deliver reliably. You're accepting reduced control in exchange for reduced responsibility.

But walk through your home and notice something missing: the clutter. The unused exercise equipment, the outdated electronics, the clothes that don't fit, the tools gathering dust. All that stuff represented failed optimization - purchases that didn't deliver the value expected, sitting idle while your life moved on.

Product-as-service promises optimization. Not perfect optimization - humans remain complex and unpredictable. But better optimization than ownership models designed to maximize production volume rather than utility delivery.

The revolution isn't really about products or services. It's about aligning incentives between producers and users toward longevity, efficiency, and satisfaction. It's about shifting from extractive economics to circular flows. It's about recognizing that prosperity isn't accumulation - it's having what you need when you need it, and nothing you don't.

That future is already arriving in pockets across industries and geographies. Whether it scales to become humanity's dominant economic paradigm or remains a niche alternative depends on decisions being made right now about business models, policies, technologies, and cultural values.

The ownership revolution is here. The question isn't whether it's coming - it's whether we'll design it wisely.

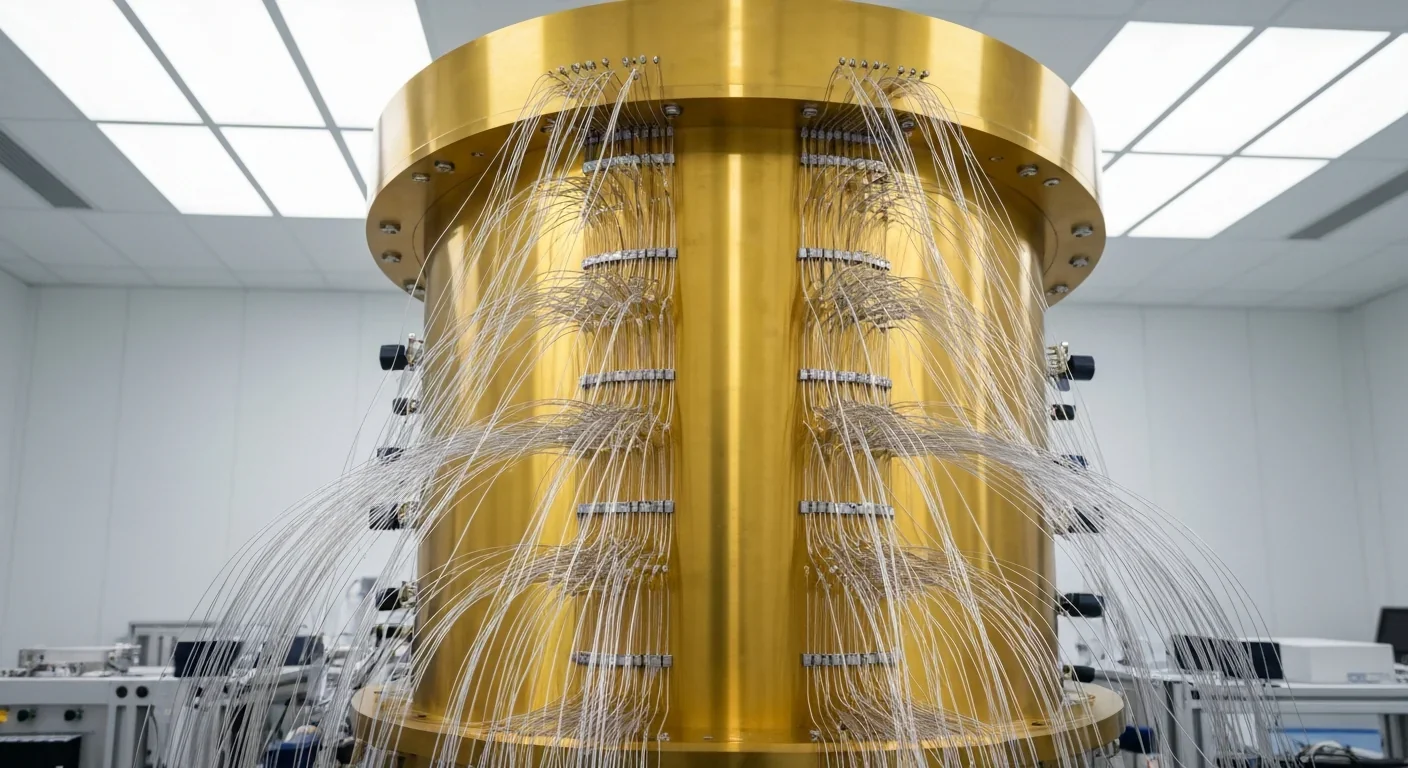

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.